Introduction to the Screwtape Lettersletters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets

Volume 35 Number 1 Article 2 10-15-2016 The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets Robert Boenig Texas A&M University in College Station, TX Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boenig, Robert (2016) "The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 35 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Plenary address, Mythcon 47. Concerns the character of the “Materialist Magician” (Screwtape’s term) in Tolkien and Lewis—the Janus-like figure who looks backward to magic and forward to scientism, without the moral core to reconcile his liminality. -

Required Independent Reading Program

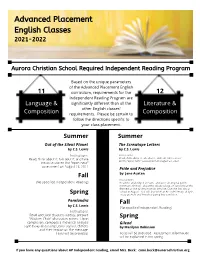

Advanced Placement English Classes 2021-2022 Aurora Christian School Required Independent Reading Program Based on the unique parameters of the Advanced Placement English 11 curriculum, requirements for the 12 Independent Reading Program are Language & significantly different than all the Literature & other English classes' Composition requirements. Please be certain to Composition follow the directions specific to your class placement. Summer Summer Out of the Silent Planet The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis by C.S. Lewis Instructions: Instructions: Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 Pride and Prejudice Fall by Jane Austen Instructions: (No specified Independent Reading) Read the unabridged version, and write an original poem - minimum 30 lines - about the ideals, values, or concerns of the Bennets or the society in which they live. Due the first day of school in August. You will also write an AP style literary analysis Spring essay on Pride and Prejudice during first semester. Perelandra Fall by C.S. Lewis (No specified Independent Reading) Instructions: Read specified chapters weekly, prepare "Wisdom Chair" discussion points. Upon Spring completion, compose a rhetorical analysis Gilead style essay discussing Lewis' stylistic choices by Marilynn Robinson and their impact on the message. Texts will be provided. Texts will be provided. Assessment information will be explained in the spring. If you have any questions about AP Independent reading, email Mrs. Beck: [email protected].. -

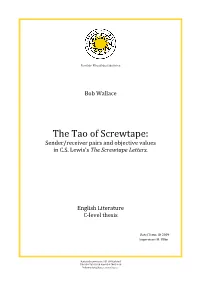

The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/Receiver Pairs and Objective Values in C.S

Estetisk- Filosofiska fakulteten Bob Wallace The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/receiver pairs and objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. English Literature C-level thesis Date/Term: Ht 2009 Supervisor: M. Ullén Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Title: The Tao of Screwtape: An examination of sender/receiver pairs for awareness of and relationship to a doctrine of objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. Author: Bob Wallace Eng C, HT 2009 Pages: 15 Abstract: The purpose of this essay is to identify the various sender/receiver pairs from C.S. Lewis’s novel The Screwtape Letters and, once identified, to examine these pairs within the context of the concept of a doctrine of universal values which is expressed in Lewis’s The Abolition of Man. For the sake of clarity and simplicity the essay begins with a definition of terms and concepts that will be used throughout, including basic terms used when discussing a communicative act: sender, receiver and message. I then explain the essays central concept which is taken from another one of Lewis’s works The Abolition of Man regarding a doctrine of objective value. The idea that a set of universal values exists is often central to secular writing and C.S Lewis, a Christian apologist, makes it clear that he believes that there exists an ethical way of living that is common to all men, Christian and non- Christian alike. He dubs this set of basic morals the Tao. -

{PDF} C. S. Lewis Signature Classic: Mere Christianity

C. S. LEWIS SIGNATURE CLASSIC: MERE CHRISTIANITY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK C. S. Lewis | 256 pages | 12 Apr 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007461219 | English | London, United Kingdom C. S. Lewis Signature Classic: Mere Christianity PDF Book With brilliantly designed, striking new covers, this beautiful boxed collection is a Christian library essential. Overcomer Movie. Lewis related his profound loss in A Grief Observed , which he published under a pseudonym. Each worth reading in its own right. Add to Wishlist. Condition: new. Published by HarperOne Lewis Signature Classics. C S Lewis. Date of Death: November 22, But, it's not incomprehensible. They did not mean, of course, that you might not find an odd individual here and there who did not know it, just as you find a few people who are colour-blind or have no ear for a tune. C S Lewis was one of the intellectual giants of the 20th century and arguably the most influential Christian writer of his day. Lewis however approaches the theme of Mere Christianity with the eye of a storyteller. Copyright c by C. Feb 29, Linda rated it it was amazing. If everyone else became equally rich, or clever, or good-looking there would be nothing to be proud about. For centuries people have been tormented by one question above all - 'If God is good and all-powerful, why does he allow his creatures to suffer pain? You may say that the Father has forgiven us because Christ died for our sins. Brought together in one volume, here are the signature spiritual works of one of the most celebrated literary figures of our time. -

Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 3 1998 Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator Diana Pavlac Glyer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Glyer, Diana Pavlac (1998) "Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Biography of Joy Davidman Lewis and her influence on C.S. Lewis. Additional Keywords Davidman, Joy—Biography; Davidman, Joy—Criticism and interpretation; Davidman, Joy—Influence on C.S. Lewis; Davidman, Joy—Religion; Davidman, Joy. Smoke on the Mountain; Lewis, C.S.—Influence of Joy Davidman (Lewis); Lewis, C.S. -

The Screwtape Letters

THE SCREWTAPE LETTERS by C. S. LEWIS Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford TO J. R. R. TOLKIEN "The best way to drive out the devil, if he will not yield to texts of Scripture, is to jeer and flout him, for he cannot bear scorn."— Luther "The devill . the prowde spirite . cannot endure to be mocked."—Thomas More Contents Preface I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI [About this etext] PREFACE I HAVE no intention of explaining how the correspondence which I now offer to the public fell into my hands. There are two equal and opposite errors into which our race can fall about the devils. One is to disbelieve in their existence. The other is to believe, and to feel an excessive and unhealthy interest in them. They themselves are equally pleased by both errors and hail a materialist or a magician with the same delight. The sort of script which is used in this book can be very easily obtained by anyone who has once learned the knack; but disposed or excitable people who might make a bad use of it shall not learn it from me. Readers are advised to remember that the devil is a liar. Not everything that Screwtape says should be assumed to be true even from his own angle. I have made no attempt to identify any of the human beings mentioned in the letters; but I think it very unlikely that the portraits, say, of Fr. -

'Epic Theatre'

Fellowship CircleSPRING 2017 COMMUNICATING THE MISSION OF FELLOWSHIP FOR PERFORMING ARTS Gifts from Fellowship Circle members provide FPA the means to produce compelling theatre from a Christian worldview that engages a diverse audience. WHAT’S INSIDE Stirring Imaginations FPA productions engage ‘ ’ audiences in New York EPIC THEATRE nd and London. – PAGE 2 FPA’s 2 New York Season Draws Spiritual Hunger Diverse Audiences and Opinions The Screwtape Letters strikes a chord in a secular society. .S. Lewis took to the stage in New York City as Fellowship for – PAGE 4 Performing Arts continues its second full season of shows in theatre’s world capital. It marked the New York premiere of a Crevamped C.S. Lewis Onstage: The Most Reluctant Convert. From the Desk of Max McLean “We made substantial enhancements in the production throughout The Enduring Relevance the past year to tell the story of C.S. Lewis’ extraordinary journey from of C.S. Lewis – PAGE 6 atheism to faith,” said FPA Artistic Director Max McLean, who tackles the role of Lewis. “We felt ready for a New York premiere after the extensive developmental process and regional productions.” SHOW SCHEDULE The Most Reluctant Convert had enjoyed a developmental production in New York in FPA’s first season; a regional premiere in Washington, D.C.; tour stops in LA, San Francisco, Cincinnati, Indy, Tulsa, Cleveland and a month-long run in Chicago. Continued on page 2 ON STAGE THE MOST RELUCTANT CONVERT “FPA OFFERS SOMETHING NEW YORK CITY Winter/Spring 2017 SORELY MISSING FROM THE NEW YORK THEATER SCENE FOR FAR TOO LONG: HIGH-QUALITY, CHALLENGING U.S. -

The Power of Prayer Dan Edit

Taking it Home: The Power of Prayer Ephesians 6:18-20 1. Journal: For the next month, record your specific prayer requests, and write down God’s answers to those requests. Each time you see God “The best thing, where it is possible, is to keep the patient answer prayer, write out a prayer of thanksgiving for his specific answer from the serious intention of praying altogether.” to your request. [The Screwtape letters, CS Lewis] 1. Prayer _________________ the voice of God and __________________ the 2. 1 Peter 3:15 says, “Be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks voice of the enemy. to give the reason for the hope that we have.” Do you feel prepared to do what the apostle commands? Spend some time asking the Lord to give “Submit yourselves, then, to God. Resist the devil and he will flee from you. you boldness (parresia) to fearlessly share the gospel to those in your Come near to God and he will come near to you.” [James 4:8] sphere of influence. Prayer must be ___________________ to the ___________________. Prayer Concerns: 2. Prayer _________________ the ________________________ of God. “Whenever there is prayer, there is danger of His own immediate action.” [The Screwtape Letters, CS Lewis] 3. Prayer _____________________ the ___________________________. “Pray also for me, that whenever I open my mouth, words may be given me so that I will fearlessly [parresia] make known the mystery of the gospel…” [Ephesians 6:19] Parresia - Outspokenness, frankness, plainness of speech that conceals nothing and passes over nothing, together with courage, confidence, boldness, fearlessness. -

Excerpts from the Screwtape Letters – by C. S. Lewis

SPX Adult Education Excerpts from The Screwtape Letters – By C. S. Lewis 4 week Book Study Sunday 9:15-10:30am beginning Nov. 26 Monday 7-8:15pm beginning Nov. 27 Only the letters (chapters) below will be discussed: Week 1 Characters: Wormwood – nephew of Screwtape Screwtape -- a mature demon instructing Wormwood in the craft of capturing human souls The Patent – a young Englishman who is Wormwood’s first prey The Enemy – God Letter 1: Reason and Reality “The trouble about argument is that it moves the whole struggle onto the Enemy’s own ground” Screwtape Sample question: What is the connection between “thinking and doing”, and how does this impact our daily lives? Letter 2: Distracting the Christian mind “The Enemy allows this disappointment to occur on the threshold of every human endeavor.” Screwtape Sample question: Screwtape claims, “One of our great allies at present is the Church itself.” What strategies might tempters employ with new Christians to create dissatisfaction with the Church? Letter 3: Relationships “You must bring him to a condition in which he can practice self-examination without discovering any of those facts about himself which are perfectly clear to anyone who has ever lived in the same house with him or worked in the same office.” Screwtape Sample question: What annoying habits of others irritate you? Which of your annoying habits do you think irritate others? Week 2 Letter 4: Sincere Prayer “It is funny how mortals always picture us as putting things into their minds: in reality our best work is done by -

The Screwtape Letters Letter 7 – Extremism

The Screwtape Letters Letter 7 – Extremism Summary Wormwood (due to youth and inexperience) has asked Screwtape if he should reveal himself to the patient. In this letter, Screwtape tells him that the current policy is to keep humans ignorant of their existence. Screwtape also follows up on a previous discussion of whether Wormwood should try to influence the man to become a fervent patriot or an extreme pacifist during the war. Screwtape advises that in the end it really does not matter as long as he misdirects the patient’s thoughts away from God. Once you have made the World an end, and faith a means, you have almost won your man, and it makes very little difference what kind of worldly end he is pursuing. - Screwtape Discussion Questions 1. According to Screwtape, what is the “cruel dilemma” demons face in deciding whether or not to making their existence known to man? (¶1) 2. Do comic figures or benign illustrations of ‘devils’ assist in the work of Screwtape and Wormwood? How does the media inhibit our belief in demons and spirits? (¶1) 3. At the time this letter was written (remember the setting is during World War II), Screwtape claims it is their policy to conceal themselves. What about today? Would you say that at the present time Screwtape would still say to keep demonic existence a secret? (¶1) 4. What does Screwtape claim is a devil’s “perfect work”? (¶1) 5. How does Screwtape explain to Wormwood the scheme behind deciding whether to lull people to complacency or to inflame them into extremism? (¶2) 6. -

If Satan Were a Nazi, Eve a Green Alien, and God a Talking Lion: C

If Satan were a Nazi, Eve a Green Alien, and God a Talking Lion: C. S. Lewis’s Novels in Creative Dialogue with Paradise Lost by David Mark Purdy Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (English) Acadia University Spring Convocation 2012 © by David Mark Purdy, 2012 (ii) This thesis by David Mark Purdy was defended successfully in an oral examination on March 19, 2012. The examining committee for the thesis was: __________________________ Dr. Zelda Abramson, Chair __________________________ Dr. Maxine Hancock, External Reader __________________________ Dr. Jessica Slights, Internal Reader __________________________ Dr. Richard Cunningham, Supervisor __________________________ Dr. Patricia Rigg, Head This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree Master of Arts (English). …………………………………………………………… (iii) I, David Mark Purdy, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. _____________________________ Author _____________________________ Supervisor _____________________________ Date (iv) Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Connecting Lewis’s fiction and Paradise Lost.........................................................3 Defining intertextual analysis…………………..............................................................8 -

A Cosmic Shift in the Screwtape Letters

Volume 39 Number 1 Article 1 Fall 10-15-2020 A Cosmic Shift in The Screwtape Letters Brenton D.G. Dickieson University of Prince Edward Island Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dickieson, Brenton D.G. (2020) "A Cosmic Shift in The Screwtape Letters," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 39 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol39/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol39/iss1/1 COSMIC SHIFT IN THE SCREWTAPE LETTERS BRENTON D.G. DICKIESON HOUGH IT WAS THE BOOK THAT LAUNCHED LEWIS INTO PUBLIC FAME, and T although he returned eighteen years later with a “Toast,” by all accounts, Lewis had no desire to capitalize on The Screwtape Letters.