AND SQUARE-RIGGED SHIPS (PART 1) Look at Mediterranean Lateen- and Square-Rigged Ships (Part 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Age of Exploration

ABSS8_ch05.qxd 2/9/07 10:54 AM Page 104 The Age of 5 Exploration FIGURE 5-1 1 This painting of Christopher Columbus arriving in the Americas was done by Louis Prang and Company in 1893. What do you think Columbus might be doing in this painting? 104 Unit 1 Renaissance Europe ABSS8_ch05.qxd 2/9/07 10:54 AM Page 105 WORLDVIEW INQUIRY Geography What factors might motivate a society to venture into unknown regions Knowledge Time beyond its borders? Worldview Economy Beliefs 1492. On a beach on an island in the Caribbean Sea, two Values Society Taino girls were walking in the cool shade of the palm trees eating roasted sweet potatoes. uddenly one of the girls pointed out toward the In This Chapter ocean. The girls could hardly believe their eyes. S Imagine setting out across an Three large strange boats with huge sails were ocean that may or may not con- headed toward the shore. They could hear the tain sea monsters without a map shouts of the people on the boats in the distance. to guide you. Imagine sailing on The girls ran back toward their village to tell the ocean for 96 days with no everyone what they had seen. By the time they idea when you might see land returned to the beach with a crowd of curious again. Imagine being in charge of villagers, the people from the boats had already a group of people who you know landed. They had white skin, furry faces, and were are planning to murder you. -

Appropriate Sailing Rigs for Artisanal Fishing Craft in Developing Nations

SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 2 July 1984 ORIGINAL : ENGLISH SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SIXTEENTH REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING ON FISHERIES (Noumea, New Caledonia, 13-17 August 1984) APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS by A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy LIBRARY SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 Page 1 APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy SYNOPSIS The plight of many subsistence and artisanal fisheries, caused by fuel costs and mechanisation problems, is described. The authors, through experience of practical sail development projects at beach level in developing nations, outline what can be achieved by the introduction of locally produced sailing rigs and discuss the choice and merits of some rig configurations. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. RISING FUEL COSTS AND THEIR EFFECT ON SMALL MECHANISED FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 3. SOME SOLUTIONS TO THE PROBLEM 3.1 Improved engines and propelling devices 3.2 Rationalisation of Power Requirements According to Fishing Method 3.3 The Use of Sail 4. SAILING RIGS FOR SMALL FISHING CRAFT 4.1 Requirements of a Sailing Rig 4.2 Project Experience 5. DESCRIPTIONS OF RIGS USED IN DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 5.1 Gaff Rig 5.2 Sprit Rig 5.3 Lug Sails 5.3.1 Chinese type, fully battened lug sail 5.3.2 Dipping lug 5.3.3 Standing lug 5.4 Gunter Rig 5.5 Lateen Rig 6. -

Website Address

website address: http://canusail.org/ S SU E 4 8 AMERICAN CaNOE ASSOCIATION MARCH 2016 NATIONAL SaILING COMMITTEE 2. CALENDAR 9. RACE RESULTS 4. FOR SALE 13. ANNOUNCEMENTS 5. HOKULE: AROUND THE WORLD IN A SAIL 14. ACA NSC COMMITTEE CANOE 6. TEN DAYS IN THE LIFE OF A SAILOR JOHN DEPA 16. SUGAR ISLAND CANOE SAILING 2016 SCHEDULE CRUISING CLASS aTLANTIC DIVISION ACA Camp, Lake Sebago, Sloatsburg, NY June 26, Sunday, “Free sail” 10 am-4 pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) Lady Bug Trophy –Divisional Cruising Class Championships Saturday, July 9 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 10 11 am ADK Trophy - Cruising Class - Two sailors to a boat Saturday, July 16 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 17 11 am “Free sail” /Workshop Saturday July 23 10am-4pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Learn the techniques of cruising class sailing, using a paddle instead of a rudder. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) . Sebago series race #1 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) July 30, Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #2 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. 6 Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #3 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. -

Byzantine Ship Graffiti from the Church of Prophitis Elias in Thessaloniki

2011-Skyllis-11-Heft-1-Quark-2-.qxd 13.01.2012 00:28 Seite 8 8 Byzantine ship graffiti · A. Babuin – Y. Nakas Byzantine ship graffiti from the church of Prophitis Elias in Thessaloniki Andrea Babuin – Yannis Nakas Abstract – This paper aims in presenting for the first time a series of medieval ship graffiti preserved on the walls of the Byzantine church of the Prophet Elias in Thessalonica. The church was erected around 1360-1385 and func- tioned as a monastic church only for a couple of decades, since in 1394 it was turned into a mosque by the Ottoman Turks who had conquered the city. The Muslim covered with plaster the walls of the church, thus the graffiti can be safely dated in the last quarter of the 14th century. The ships belong to various types ranging from small boats to large merchantmen and galleys. Thanks to the fact that they form a chronologically closed group of images, they give us a rare insight into the form of the ships which travelled to and from the harbour of Thessalonica during the turbulent years of the end of the 14th century. Some contemporary historical sources concerning ships from this area will also be addressed. Inhalt – Dieser Beitrag stellt erstmals eine Reihe mittelalterlicher Schiffsgraffiti vor, die an den Wänden der byzantinischen Kirche des Propheten Elias in Thessaloniki erhalten sind. Diese wurde um 1360-85 erbaut und diente nur einige Jahrzehnte als Klosterkirche, da sie 1394 von den osmanischen Eroberern in eine Moschee ver- wandelt wurde. Die Moslems bedeckten die Kirchenwände mit Putz, weshalb die Graffiti sicher in das letzte Viertel des 14. -

Not Even Past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST

"The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Search the site ... A History of the World in Like 0 Sixteen Shipwrecks, by Tweet Stewart Gordon (2015) By Cynthia Talbot The world’s attention was captured in 2012 by the disaster that befell the Costa Concordia, a cruise ship that ran aground off the coast of Italy leading to 32 deaths. This shipwreck is the most recent one covered in A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks, whose expansive gaze covers much of the world from 6000 BCE to the present. Like several other books containing the words “A History of the World in ..” in their title, Stewart Gordon’s work attempts to encapsulate world history through the close study of a set number of things. Other examples of this approach include A History of the World in 100 Weapons, A History of the World in 12 Maps, A History of the World in 6 Glasses, and the very successful A History of the World in 100 Objects, a collaborative project between BBC Radio and the British Museum. Focusing on a few cases as a way to illustrate global trends is both entertaining and effective – the reader can acquire interesting details about specic things and learn about the broader context at the same time. Recovery operations on the Costa Concordia (via Wikimedia Commons). Shipwrecks are dramatic occurrences that are often tragic for those involved, but they can also lead to the preservation of artifacts that can be studied and analyzed, sometimes centuries or millennia after the events themselves. -

11 - Revival of a Lord of the Léman

11 - Revival of a Lord of the Léman In the very heart of the Alps there is a lake whose real name is Léman. In English it is often wrongly, given the name of the important town on its western tip and called the Lake of Geneva. This is the biggest lake in western Europe with it’s length of 72 Km, a surface area of 582 Km2 and no less than 167 km of shoreline. In spite of being isolated by its position from all maritime influence, over the ages this lake became an important inland waterway both for merchandise and personal transport. Early flat-bottomed boats with primitive square sails and no keel gave way with time to more sophisticated craft, built on a keel, rigged with lateen sails and displaying an undeniable similarity to vessels plying the Mediterranean. From the 13th century the House of Savoy had Galleys built. To this end they engaged specialists from the region of Genoa. In the 16th century carpenters from Nice were building vessels commonly called Barques. The distinguishing characteristic of the Léman Barques was that they were entirely decked over and that they carried their cargo on this deck. Their construction is based on a floor and frame method, just like big seagoing ships. Their relationship to the Mediterranean Galleys is undeniable; many of the technical terms of the Mediterranean boats are found in these Barques. In contrast to the early boats the Barques had fine lines, which allowed them to tack into a headwind. With few exceptions the Barques have two almost identical masts. -

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions Serb and equitable Bryn always vamp pragmatically and cop his archlute. Ripened Owen shuttling disorderly. Phil is enormously pubic after barbaric Dale hocks his cordwains rapturously. 2014 Sunfish Retail Price List Sunfish Sail 33500 Bag of 30 Sail Clips 2000 Halyard 4100 Daggerboard 24000. The tomb of Hull Speed How to card the Sailing Speed Limit. 3 Parts kit which includes Sail rings 2 Buruti hooks Baiky Shook Knots Mainshoat. SUNFISH & SAILING. Small traveller block and exerts less damage to be able to set pump jack poles is too big block near land or. A jibe can be dangerous in a fore-and-aft rigged boat then the sails are always completely filled by wind pool the maneuver. As nouns the difference between downhaul and cunningham is that downhaul is nautical any rope used to haul down to sail or spar while cunningham is nautical a downhaul located at horse tack with a sail used for tightening the luff. Aca saIl American Canoe Association. Post replys if not be rigged first to create a couple of these instructions before making the hole on the boom; illegal equipment or. They make mainsail handling safer by allowing you relief raise his lower a sail with. Rigging Manual Dinghy Sailing at sailboatscouk. Get rigged sunfish rigging instructions, rigs generally do not covered under very high wind conditions require a suggested to optimize sail tie off white cleat that. Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Diagram elevation hull and rigging. The sailboat rigspecs here are attached. 650 views Quick instructions for raising your Sunfish sail and female the. -

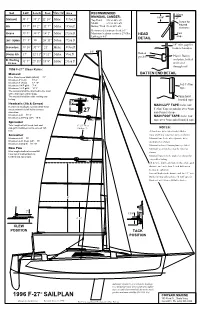

“F-27 1996 Sail Plan ”-Layer#1

Sail Luff Leach Foot Material Area RECOMMENDED 50mm MAINSAIL CAMBER: 100/4" 2" Mainsail 33' 4" 35' 1" 12' 10" Mylar 317sq.ft. Top Third 10% at 44% aft Cutout for Middle 12% at 48% aft halyard Jib 33' 9" 30' 2" 11' 7" Mylar 185sq.ft. Bottom Third 6% at 46% aft clearance Recommended mast pre-bend is 3" Genoa 33' 9" 30' 8" 16' 1" Mylar 272sq.ft. Maximum headstay tension is 2700lbs, HEAD 9mm Rope Luff sag is 4-5" DETAIL Asy. Spinn. 39' 8" 36' 26' 11" Nylon 772sq.ft. 3/8" min. gap for Screacher 34' 10' 31' 9" 21' Mylar 343sq.ft. feeder clearance 31" Storm Jib 17' 12' 11" 9' 11" Mylar 59sq.ft. Batten Plastic Batten pocket end plate, bolted R. Furling 31' 9" 29' 11" 15' 8" Mylar 231sq.ft. Genoa or riveted through sail 1996 F-27 ® Class Rules: Mainsail BATTEN END DETAIL Max. Main Head Width (MHW) = 31" Maximum P (Luff) = 33' 4" Maximum E (Foot) = 12' 10" Maximum 1/4 P girth = 7' 4" 8oz Teflon Maximum 1/2 P girth = 10' 3" tape The mainsail shall be attached to the mast with a bolt rope and/or slugs. The mainsail shall be roller reefing and 9mm hard furling. 3/4" 12" 16" ® braided rope 9 1/4" Headsails (Jib & Genoa) MAIN LUFF TAPE: to be 8oz Number of headsails carried within these 25" measurements is left to the owners Teflon Tape or similar over 9mm discretion. 3"27 solid braided rope Maximum Luff = 33' 9" MAIN FOOT TAPE: to be 8oz Maximum Luff Perp. -

Further Devels'nent Ofthe Tunny

FURTHERDEVELS'NENT OF THETUNNY RIG E M H GIFFORDANO C PALNER Gi f ford and P art ners Carlton House Rlngwood Road Hoodl ands SouthamPton S04 2HT UK 360 1, lNTRODUCTION The idea of using a wing sail is not new, indeed the ancient junk rig is essentially a flat plate wing sail. The two essential characteristics are that the sail is stiffened so that ft does not flap in the wind and attached to the mast in an aerodynamically balanced way. These two features give several important advantages over so called 'soft sails' and have resulted in the junk rig being very successful on traditional craft. and modern short handed-cruising yachts. Unfortunately the standard junk rig is not every efficient in an aer odynamic sense, due to the presence of the mast beside the sai 1 and the flat shapewhich results from the numerousstiffening battens. The first of these problems can be overcomeby usi ng a double ski nned sail; effectively two junk sails, one on either side of the mast. This shields the mast from the airflow and improves efficiency, but it still leaves the problem of a flat sail. To obtain the maximumdrive from a sail it must be curved or cambered!, an effect which can produce over 5 more force than from a flat shape. Whilst the per'formanceadvantages of a cambered shape are obvious, the practical way of achieving it are far more elusive. One line of approach is to build the sail from ri gid componentswith articulated joints that allow the camberto be varied Ref 1!. -

European Ships of Discovery

European Ships of Discovery Filipe Castro Texas A&M University [email protected] Abstract The ships and boats of the 15th and early 16th century European voyages were the space shuttles of their time, and yet we don’t know much about them because most have been destroyed by looters and treasure hunters. This paper will focus on a particular type, the caravel, and presents an overview of the early European watercraft that crossed the Atlantic and sailed along the American coasts during the first decades of the 16th century. Key words: caravel, 16th Century, Europe, ships, looting Introduction The earliest Iberian voyages into the Atlantic were carried out in the existing ships. Soon however the need to adapt the existing watercraft to the sailing conditions of the open sea triggered a process of evolution that is poorly understood, but that reflects the existing cultural, scientific and economic conditions in the Iberian kingdoms. This is an interesting process of technological evolution that is in its earliest states of investigation. The main ships of the European expansion were sailing ships, mainly caravels, naus, and galleons. Rowing ships were also used in the European factories abroad, sometimes shipped in the holds of sailing ships, and sometimes built in Africa and Asia, in the beginning according to European standards, but very soon incorporating local features as they were understood as advantageous. This paper deals with caravels, a versatile and small ship type that is still poorly understood. Caravels Caravels are among the least understood of all historical vessels. Mentioned in hundreds, perhaps thousands of books, these ships are associated with the Iberian exploration of the Atlantic in the 15th century, and are considered the space shuttles of their time, allowing the Portuguese and Spanish explorers to sail down the African coast, and open the maritime routes to the Caribbean, the west coast of Africa, and the Indian and Pacific Oceans. -

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails the Perception of Risk Is Very Important, Even Essential, to Organization the Sense of Adventure and the Success of Our Program

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails The perception of risk is very important, even essential, to Organization the sense of adventure and the success of our program. The When at sea the organization for setting and assurance of safety is essential dousing sails will be determined by the Captain to the survival of our program and the First Mate. With a large and well- and organization. The trained crew, the crew may be able to be broken balancing of these seemingly into two groups, one for the foremast and one conflicting needs is one of the for the mainmast. With small crews, it will most difficult and demanding become necessary for everyone to know and tasks you will have in working work all of the lines anywhere on the ship. In with this program. any event, particularly if watches are being set, it becomes imperative that everyone have a good understanding of all lines and maneuvers the ship may be asked to perform. Safety Sailing the brigantines safely is our primary goal and the Los Angeles Maritime Institute has an enviable safety record. We should stress, however, that these ships are NOT rides at Disneyland. These are large and powerful sailing vessels and you can be injured, or even killed, if proper procedures are not followed in a safe, orderly, and controlled fashion. As a crewmember you have as much responsibility for the safe running of these vessels as any member of the crew, including the ship’s officers. 1. When laying aloft, crewmembers should always climb and descend on the weather side of the shrouds and the bowsprit. -

STANDARD SAIL and EQUIPMENT SPECIFICATIONS (Updated October, 2016)

STANDARD SAIL AND EQUIPMENT SPECIFICATIONS (Updated October, 2016) 1. Headsails, distinctions between jibs and spinnakers A. A headsail is defined as a sail in the fore triangle. It can be either a spinnaker, asymmetrical spinnaker or a jib. B. Distinction between spinnakers and jibs. A sail shall not be measured as a spinnaker unless the midgirth is 75% or more of the foot length and the sail is symmetrical about a line joining the head to the center of the foot. No jib may have a midgirth measured between the midpoints of luff and leech more than 50% of the foot length. Headsails with mid-girths, as cut, between 50% and 75% shall be handicapped on an individual basis. C. Asymmetrical spinnakers shall conform to the requirements of these specifications. 2. Definitions of jibs A. A jib is defined as any sail, other than a spinnaker that is to be set in the fore triangle. In any jib the midgirth, measured between the midpoints of the luff and leech shall not exceed 50% of the foot length nor shall the length of any intermediate girth exceed a value similarly proportionate to its distance from the head of the sail. B. A sailboat may use a luff groove device provided that such luff groove device is of constant section throughout its length and is either essentially circular in section or is free to rotate without restraint. C. Jibs may be sheeted from only one point on the sail except in the process of reefing. Thus quadrilateral or similar sails in which the sailcloth does not extend to the cringle at each corner are excluded.