259 Re-Regulating the Deregulated – a Case Study of the Scottish Bus Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Regeneration Issue 30 (Spring 2005)

Scottish Urban Regeneration Forum issue 30 : spring 2005 scotregensharing experience : shaping practice In this issue: • Cultural Planning, Liz Gardner and Lia Ghilardi – pg 1 and 3 • Making Waves, Cllr. Charlie Gordon – pg 8 • Coastal towns report, Roland Hahn – pg 4 • Financial Inclusion conference report, Mike Chapman – pg 12 • Congestion Charges, Cllr Andrew Burns – pg 6 • The Northern Way, Vince Taylor – pg 13 • and much more... now read on... Self Image- Artist Steven Healy's photo is part of the 'Mongrel' photography project commissioned Thinking by the Royston Road Association Culture CULTURAL PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PLANNING - a recipe for success? Liz Gardiner of Fablevision and Cultural Planning Consultant Lia Ghilardi, from the National Cultural Planning Steering Group, make the case for culture as an essential element of successful regeneration strategies. What is a joined-up Cultural Planning approach? A Cultural Planning approach starts not from the identification of all In Scotland and elsewhere, at neighbourhood, city, regional and the problems in a community and addressing them one by one or national levels, there is a growing realisation that culture can deliver separately. Instead it takes a holistic approach and puts culture and on many aspects of community engagement, empowerment and people at the core. It addresses jobs, training for employment, the leadership. However, so far, the policy framework for implementing development of new small to medium sized enterprises, planning, integrated cultural planning projects and schemes is still relatively and regeneration, but never in isolation from each other. underdeveloped. Many local authorities and community regeneration bodies still see culture as an add-on to existing The Cultural Planning approach has emerged as a way of enabling programmes. -

Ag/S3/11/06 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU

Ag/S3/11/06 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU AGENDA FOR MEETING ON TUESDAY 22 FEBRUARY 2011 2 pm: Room Q1.03 1. Minutes (a) Draft minutes of 8 February 2011 (attached) (b) Matters arising 2. Future Business Programme (PB/S3/11/22) Procedural motions 3. Scottish Statutory Instruments (PB/S3/11/23) Legislation 4. Public Records (Scotland) Bill – Stage 2 referral and timetable (PB/S3/11/24) 5. Removal of motions from the Business Bulletin (PB/S3/11/25) 6. Publication scheme – consideration of any exempt papers 7. Date of next meeting – Tuesday 1 March 2011 PB/S3/11/22 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU POSSIBLE MOTIONS FOR MEMBERS BUSINESS 1. Bureau Members will be aware that under Rule 5.6.1(c) the Bureau has a duty to ensure that there is a period of time available for Members’ Business following Decision Time. 2. Motions submitted for Members’ Business are shown below. S3M-7898# Duncan McNeil: 30th Anniversary of the Lee Jeans Sit-in—That the Parliament remembers the 240 women who staged what it sees as a historic sit-in at the Lee Jeans factory in Greenock 30 years ago, beginning on 5 February 1981; notes that the workers barricaded themselves into the canteen for seven months in protest at the decision to close the factory; salutes the workers for capturing the imagination of the whole country and achieving a landmark victory against a US multinational; wishes the former convener, Helen Monaghan, and machinists, Margaret Wallace and Catherine Robertson, well for the 30th anniversary reunion event that they have organised, and considers the Lee Jeans sit-in to be an inspiration to women workers all over the world. -

Regulation of Bus Services Bill PUBLIC CONSULTATION DOCUMENT

Regulation of Bus Services Bill PUBLIC CONSULTATION DOCUMENT CHARLIE GORDON MSP www.charliegordonmsp.com 2 Regulation of Bus Services Bill LIST OF CONTENTS Section 1 Introductory Summary PAGES 3-7 Section 2 Legislative Background PAGES 8-10 Section 3 Bus Operations PAGES 11-16 Section 4 Public Funding For Buses PAGES 17-18 Section 5 Bus Policy PAGES 19-23 Section 6 Free Bus Travel PAGES 24-28 Section 7 Bus Workers PAGES 29-30 Section 8 List of References PAGE 31 Section 9 Glossary PAGE 32 Section 10 Acknowledgements PAGE 33 Section 11 Charlie Gordon MSP – Biographical Notes PAGE 34 Section 12 Responding to this Proposal PAGES 35-39 www.charliegordonmsp.com 3 Section 1: Introductory Summary Buses are the most commonly used form of public transport in Scotland and provide a vital service. There has been a growth in bus patronage in six of the last seven years, reversing a longer-term decline. Some 482 million passenger journeys were made by bus in 2006/07 the highest figure in a decade. A total of 322m vehicle kilometres were covered by commercial services, 55m vehicle km by subsidised services and an unknown distance by community trans - port organisations. The Scottish Government and local authorities spent more than £ 250 million on support for bus services in 2006/07. But, despite this significant public investment, there is little regulation of how the bus industry used this money to improve services for travellers. Under exist - ing rules, councils only have powers to dictate timetables and fares in very lim - ited circumstances , and the Traffic Commissioner who acts as the UK Government ' s bus watchdog , tries to ensure that bus operators keep to regis - tered and advertised timetables and operate safe and roadworthy vehicles. -

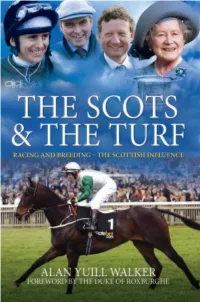

T Am T Th T Be an C M in Fo Co Fa Gr W St Ch T Ra Sm in R No T Str W Fa

As a freelance writer, Alan Yuill Walker has spent The Scots & The Turf tells the story of the his life writing about racing and bloodstock. For amazing contribution made to the world of over forty years he was a regular contributor to Thoroughbred horseracing by the Scots and Horse & Hound and has had a long involvement those of Scottish ancestry, past and present. with the Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association. Throughout the years, this contribution has Other magazines/journals to which he has been across the board, from jockeys to trainers contributed on a regular basis include The and owners as well as some superb horses. British/European Racehorse, Stud & Stable, Currently, Scotland has a great ambassador in Pacemaker, The Thoroughbred Breeder and Mark Johnston, who has resurrected Middleham Thoroughbred Owner & Breeder. He was also in North Yorkshire as one of the country’s a leading contributor to The Bloodstock foremost training centres, while his jumping Breeders’ Annual Review. His previous books counterpart Alan King, the son of a Lanarkshire are Thoroughbred Studs of Great Britain, The farmer, is now based outside Marlborough. The History of Darley Stud Farms, Months of Misery greatest lady owner of jumpers in recent years Moments of Bliss, and Grey Magic. was Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, while Stirling-born Willie Carson was five-times champion jockey on the Flat. These are, of course, familiar names to any racing enthusiast but they represent just a small part of the Scottish connection that has influenced the Sport of Kings down the years. Recognition of the part played by those from north of the Border is long overdue and The Scots & The Turf now sets the record straight with a fascinating account of those who have helped make horseracing into the fabulous spectacle it is today. -

Decision 132/2008 Mr Paul Drury and Glasgow City Council

Decision 132/2008 Mr Paul Drury and Glasgow City Council Correspondence exchanged between two individuals Reference No: 200800444 Decision Date: 9 October 2008 Kevin Dunion Scottish Information Commissioner Kinburn Castle Doubledykes Road St Andrews KY16 9DS Tel: 01334 464610 Decision 132/2008 Mr Drury and Glasgow City Council Summary Mr Paul Drury requested all correspondence between Charlie Gordon MSP and the Council’s Chief Executive and Solicitor relating to the redevelopment of the Pollok Shopping Centre at Silverburn and the Darnley Mains planning applications from Glasgow City Council (the Council). The Council responded by advising Mr Drury that it did not hold the information he was seeking. Following a review, Mr Drury remained dissatisfied and applied to the Commissioner for a decision. Following an investigation, the Commissioner found that the Council had dealt with Mr Drury’s request for information in accordance with Part 1 of FOISA by giving Mr Drury notice, in terms of section 17 of FOISA, that it did not hold the information he was seeking. Relevant statutory provisions and other sources Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 (FOISA) sections 1(1) (General entitlement) and 17(1) (Notice that information is not held) The full text of each of the statutory provisions referred to above is reproduced in the Appendix to this decision. The Appendix forms part of this decision. Background 1. On 11 December 2007, Mr Drury sent two emails to Glasgow City Council (the Council) requesting the following information: • Request 1: All correspondence (email, memo or letter) between Charlie Gordon (an MSP, who previously served as leader of the Council) and the Council’s Chief Executive and Solicitor on the subject of the redevelopment of the Pollok Shopping Centre as Silverburn (to include references to planning applications and the sale of any council-owned land). -

Urban Strategy Or Urban Solution?: Visions of a Gentrified Waterfront in Rotterdam and Glasgow Brian Doucet U

Urban strategy or urban solution?: Visions of a gentrified waterfront in Rotterdam and Glasgow Brian Doucet Utrecht University Conference Paper Association of American Geographers 2013 PortcityScapes Special Session Friday 12 April 2013 This is a draft paper. Please do not cite without consultation with the author Abstract The transformation of old inner‐city harbour areas into mixed‐use, high‐end flagship developments is one of the biggest processes of urban change impacting port cities. These spaces are part of the gentrified urban landscape, which, as recent scholarship has demonstrated, is largely state‐ or municipally‐led. Our currently knowledge on the goals of gentrification focuses on three objectives: urban entrepreneurial policies of growth and place promotion, creating liveable cities and neighbourhoods and ‘revanchist’ attitudes towards poor and marginalised groups. However, we lack a deep understanding of the visions and ideas of key initiators of municipally‐led gentrification; these first‐hand accounts tend to get ignored when examining gentrification as an urban strategy more broadly. Therefore, the aim of this article is to gain more insight into these visions which drive municipal leaders to promote gentrified spaces along their urban waterfronts. It will examine the specific cases of high‐end, mixed‐use developments in Rotterdam and Glasgow. Both waterfronts were championed by individual leaders whose visions led to the transformation of their respective waterfronts from industrial or abandoned places to post‐industrial, consumption‐oriented spaces. A detailed analysis of these visions reveals that they are clearly rooted in addressing key social and economic problems of their cities: in Rotterdam this is centred on the divisions between the northern and southern halves of the city; in Glasgow, it is focused on employment opportunities. -

Fact Sheet Session 3 Msps Not Standing Or Not Returned in the 2011 Election 6 May 2011 Msps: Historical Series

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament I nfor mation C entre l ogo Scottish Parliament Fact sheet Session 3 MSPs Not Standing or Not Returned in the 2011 Election 6 May 2011 MSPs: Historical Series 48 Session 3 MSPs were not returned to the Scottish Parliament in Session 4. They either did not stand as a candidate for re-election, or they stood but were not re-elected. This fact sheet is divided into two sections. The first section lists those MSPs who stood for re- election but failed to win a seat. The second section lists those MSPs who were serving at the end of Parliamentary Session 3 (22 March 2011) but chose not to stand for re-election. Abbreviation Party Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Ind Independent Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats NPA No Party Affiliation Session 3 MSPs who stood for re-election in 2011 but failed to win a seat: MSP Party Constituency (C) or Region (R) Robert Brown LD Glasgow (R) Derek Brownlee Con East Lothian (C), South Scotland (R) Bill Butler Lab Glasgow Anniesland (C) Cathie Craigie Lab Cumbernauld and Kilsyth (C) Ross Finnie LD Greenock and Inverclyde (C), West Scotland (R) Karen Gillon Lab Clydesdale (C) Charlie Gordon Lab Glasgow Cathcart (C) Andy Kerr Lab East Kilbride (C) Marilyn Livingstone Lab Kirkcaldy (C) Frank McAveety Lab Glasgow Shettleston (C) Tom McCabe Lab Hamilton, Larkhall & Stonehouse (C) Anne McLaughlin SNP Glasgow Provan (C), Glasgow (R) Pauline McNeill Lab Glasgow Kelvin (C) Des McNulty Lab Clydebank and Milngavie (C) -

Ag/S3/10/17 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU

Ag/S3/10/17 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU AGENDA FOR MEETING ON TUESDAY 11 MAY 2010 2.00pm: Room Q1.03 1. Minutes (a) Draft minutes of 4 May 2010 (attached) (b) Matters arising 2. Future Business Programme (PB/S3/10/84) Legislation 3. (a) Historic Environment (Amendment) (Scotland) Bill – Stage 1 referral (PB/S3/10/85) 4. Opposition business allocation 2010-2011 (PB/S3/10/86) 5. Publication scheme – consideration of any exempt papers 6. Date of next meeting – Tuesday 18 May 2010 PB/S3/10/84 PARLIAMENTARY BUREAU POSSIBLE MOTIONS FOR MEMBERS BUSINESS 1. Bureau Members will be aware that under Rule 5.6.1(c) the Bureau has a duty to ensure that there is a period of time available for Members’ Business following Decision Time. 2. Motions submitted for Members’ Business are shown below. S3M-6236# Stewart Maxwell: 65th Anniversary of VE Day—That the Parliament commemorates the 65th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day (VE Day) when on 8 May 1945 the Allied Forces formally accepted the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany; honours the contribution by veterans of all ages and from all conflicts; believes that there should be greater recognition of war veterans in Scotland, many of whom sustained severe physical or mental injuries in defending their country, and encourages veterans to take advantage of their eligibility for the Veterans’ Badge, a small, but visible token of society’s appreciation of their service. Supported by: Rob Gibson, Brian Adam, Maureen Watt, Andrew Welsh, Bob Doris, Des McNulty, Kenneth Gibson, Dave Thompson, Tricia Marwick, Stuart -

Fact Sheet Msps with Dual Mandates 12 January 2016 Msps: Current Series

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament I nfor mation C entre l ogo Scottish Parliament Fact sheet MSPs with Dual Mandates 12 January 2016 MSPs: Current Series This fact sheet lists all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who currently hold a dual mandate. It also lists the MSPs that held dual mandates in previous sessions. Dual mandate is the term used to describe those MSPs who, in addition to their seat in the Scottish Parliament, also hold a seat in either the House of Commons (MPs), House of Lords (Peers) or represent a ward in their local council (councillors). This fact sheet lists the name of the MSP, their party and the constituency or region that they represent in the Scottish Parliament. It also lists the area that they represent in the House of Commons or in local government or their title (if they are a peer). Finally, this document also provides information on the start and end dates of dual mandates. It should be noted that no MSP has held a dual mandate through also holding a seat in the European Parliament. Abbreviations used: C Constituency Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats R Region SNP Scottish National Party Session 4 MSPs with Dual Mandates (5 May 2011 to date) MSPs who are also MPs Name of MSP Party MSP for MP for Additional Notes Alex Salmond1 SNP Aberdeenshire Gordon East (C) MSPs who are also Members of the House of Lords Name of MSP Party MSP for Title Additional Notes Annabel Goldie Con West Scotland (R) Baroness Goldie of Bishopton MSPs who are also Councillors Name of MSP Party MSP for Councillor for Notes Lesley Brennan2 Lab North East Scotland Dundee East End MSPs in Session 4 who were also Councillors Name of MSP Party MSP for Councillor for Notes Did not stand for re- election in George Adam SNP Paisley Paisley South 2012 local council election Did not stand for re- election in Clare Adamson SNP Central Scotland (R) Wishaw 2012 local council election 1 Alex Salmond was elected in the general election on 7 May 2015. -

Spice Briefing

LIST OF ALL MSPS A-Z: SESSION 2 Scottish Parliament The Fact sheet provides an alphabetical list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the second Fact sheet parliamentary session, 7 May 2003 – 2 April 2007. It also lists the party for which each MSP was elected as well as the constituency or region that they represented. MSPs: Historical The abbreviation (C) has been used to indicate a constituency seat Series and (R) to indicate a regional seat. 12 March 2009 1 MSP Party Constituency or Region Brian Adam Scottish National Party Aberdeen North (C) Bill Aitken Conservative Glasgow (R) Wendy Alexander Labour Paisley North (C) Andrew Arbuckle1 Liberal Democrat Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Jackie Baillie Labour Dumbarton (C) Shiona Baird Green North East Scotland (R) Richard Baker Labour North East Scotland (R) Chris Ballance Green South of Scotland (R) Mark Ballard Green Lothians (R) Scott Barrie Labour Dunfermline West (C) Sarah Boyack Labour Edinburgh Central (C) Rhona Brankin Labour Midlothian (C) Ted Brocklebank Conservative Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Robert Brown Liberal Democrat Glasgow (R) Derek Brownlee2 Conservative South of Scotland (R) Bill Butler Labour Glasgow Anniesland (C) Rosemary Byrne3 Scottish Socialist Party South of Scotland (R) Dennis Canavan Independent Falkirk West (C) Malcolm Chisholm Labour Edinburgh North and Leith (C) Cathie Craigie Labour Cumbernauld and Kilsyth (C) Bruce Crawford Scottish National Party Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Roseanna Cunningham Scottish National Party Perth (C) Frances Curran Scottish Socialist Party West of Scotland (R) Margaret Curran Labour Glasgow Baillieston (C) David Davidson Conservative North East Scotland (R) Susan Deacon Labour Edinburgh East and Mussleburgh (C) James Douglas-Hamilton Conservative Lothians (R) Helen Eadie Labour Dunfermline East (C) Fergus Ewing Scottish National Party Inverness East, Nairn and Lochaber (C) 1 Andrew Arbuckle became the regional member for Mid Scotland and Fife on 10 January 2005. -

Official Report of Our Will Be Fairly Busy—The Minister Will Be Discussing Previous Meeting

EUROPEAN AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS COMMITTEE Tuesday 6 December 2005 Session 2 £5.00 Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2005. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Licensing Division, Her Majesty‟s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax 01603 723000, which is administering the copyright on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. Produced and published in Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body by Astron. CONTENTS Tuesday 6 December 2005 Col. EUROPEAN COMMISSION WORK PROGRAMME 2006 ................................................................................. 1553 IMPROVING ENGAGEMENT WITH THE EUROPEAN UNION ............................................................................. 1559 PRE AND POST-COUNCIL SCRUTINY........................................................................................................ 1562 SIFT .................................................................................................................................................. 1567 CONVENER’S REPORT .......................................................................................................................... 1568 EUROPEAN AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS COMMITTEE 18th Meeting 2005, Session 2 CONVENER *Linda Fabiani (Central Scotland) (SNP) DEPU TY CONVENER *Irene Oldfather (Cunninghame South) (Lab) COMMI TTEE MEMBERS Dennis Canavan (Falkirk West) (Ind) *Mrs Margaret Ewing (Moray) (SNP) *Phil Gallie (South of Scotland) -

Spice Briefing Election 2011

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament Infor mation C entre l ogos. SPICe Briefing Election 2011 10 May 2011 11/29 Stephen Herbert, Ross Burnside, Murray Earle, Greig Liddell and Iain McIver This paper provides an analysis of the 2011 Scottish Parliament election. In particular, it considers the Scottish Parliament electoral system, the election campaign, electoral behaviour, the impact of the result upon the political parties, and the new composition of the Parliament. The briefing also contains perspectives on the election from a range of external commentators. The views expressed by these authors are their own and do not represent the views of SPICe or of the Scottish Parliament. The external commentators are: Angus MacLeod, Scottish Political Editor, The Times Charlie Jeffrey, Professor of Politics and Director of the Academy of Government at the University of Edinburgh John Curtice, Professor of Politics, University of Strathclyde Paul Cairney, Senior Lecturer in Politics, University of Aberdeen Peter Lynch, Senior Lecturer in Politics, University of Stirling The electoral data set out in this paper are provisional, based primarily upon the returns from Returning Officers, available at the time of publication. The authors wish to express their thanks to Professor David Denver, of Lancaster University, for permission to use his 2007 notional results data. CONTENTS THE ELECTION RESULT: SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 3 THE