Soldier, PR Man, Journalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

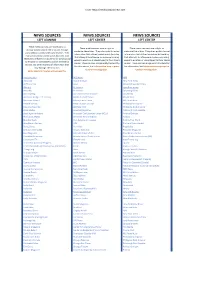

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

5Th Grade Big Idea Study Guides

5th Grade Big Idea Study Guides B ig Ideas 1 & 2 Study Guide: Nature of Science Types of Scientific Investigations: Type of Investigation Description Model a representation of an idea, an object, a process, or a system that is used to describe and explain something that cannot be experienced directly. Simulation an imitation of the functioning of a system or process Systematic Observations documenting descriptive details of events in nature –amounts, sizes, colors, smell, behavior, texture - for example - eclipse observations Field Studies studying plants and animals in their natural habitat Controlled Experiment an investigation in which scientists control variables and set up a test to answer a question. A controlled experiment must always have a control group (used as a comparison group) and a test group. ALL types of Scientific Investigation include making observations and collecting evidence. Observations: ALL scientists make observations. An observation is information about the natural world that is gathered through one of the five senses. An observation is something you see, hear, taste, touch, or smell. List 5 Examples of Observations 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Evidence Evidence is information gathered when scientists make systematic observations or set up an experiment to collect and record data. The data recorded is then analyzed by the scientists in order to base conclusions on the evidence collected. The collection of evidence is a critical part of a scientific investigation. Although the scientific method does not always follow a rigidly defined set of steps, a scientific investigation is only valid if it is based on observations and evidence. Controlled Experiments A controlled experiment is different than all other types of scientific investigations because in an experiment, variables are being controlled by the scientist in order to answer a question. -

Editor & Publisher

NEW YORK WORLD-TELEGRAM BUYS THE NEW YORK SUN EDITOR & PUBLISHER THE FOURTH ESTATE SUITE 1700 TIMES TOWER " 1475 BROADWAY, NEW YORK 18, N. Y. Reentered as Second Class Matter January 13. 1945. at the Post Office at New York. N. Y.. under the Act of March 3. 1879 Copyright 1950, The Editor & Publisher Co., Inc. I VOL. 83, NO.I additionalEvery Saturdayissue in withJanuary JANUARY 7, 1950 $5.50$5.00 inper Canada;year $6.00in U. ForeignS. A.; ISc PER COPY e "HUMAN THmECOENE SECONDS'A .......... .................... ....................... Bold Experiment Here Brings Aid to Retarded Children The Dramatic Story Of a Heartwarming Project Parents of retarded children watch progress of their (A group of Chicago parents, faced with the heartbreaking youngsters through a screened window. They can see inside fact that their mentally retarded children could not be educated the classroom, but cannot be seen themselves. in the normal way, decided to do something about it themselves. Here is the dramatic story of what they did. First of three articles. BY NORINE FOLEY ............. .................................... This is a story never before told of an experiment never before attempted. It is a story of mentally deficient children-rejected by public schools as "ineducable"--and what happened when their parents determined something should be done for them. Eyes of educators throughout the country are upon 10 children I in an old red brick building at 2150 W, North av. Map P North and South Side divi- Other eyes are upon them, too.l sions were organized by the Assn- Mothers stand on chairs outside FeC parents to work through on House for future meet- classrooms at Association House, retarded Children a Near North Side community children center. -

You Are What You Read

You are what you read? How newspaper readership is related to views BY BOBBY DUFFY AND LAURA ROWDEN MORI's Social Research Institute works closely with national government, local public services and the not-for-profit sector to understand what works in terms of service delivery, to provide robust evidence for policy makers, and to help politicians understand public priorities. Bobby Duffy is a Research Director and Laura Rowden is a Research Executive in MORI’s Social Research Institute. Contents Summary and conclusions 1 National priorities 5 Who reads what 18 Explaining why attitudes vary 22 Trust and influence 28 Summary and conclusions There is disagreement about the extent to which the media reflect or form opinions. Some believe that they set the agenda but do not tell people what to think about any particular issue, some (often the media themselves) suggest that their power has been overplayed and they mostly just reflect the concerns of the public or other interests, while others suggest they have enormous influence. It is this last view that has gained most support recently. It is argued that as we have become more isolated from each other the media plays a more important role in informing us. At the same time the distinction between reporting and comment has been blurred, and the scope for shaping opinions is therefore greater than ever. Some believe that newspapers have also become more proactive, picking up or even instigating campaigns on single issues of public concern, such as fuel duty or Clause 28. This study aims to shed some more light on newspaper influence, by examining how responses to a key question – what people see as the most important issues facing Britain – vary between readers of different newspapers. -

Cotwsupplemental Appendix Fin

1 Supplemental Appendix TABLE A1. IRAQ WAR SURVEY QUESTIONS AND PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES Date Sponsor Question Countries Included 4/02 Pew “Would you favor or oppose the US and its France, Germany, Italy, United allies taking military action in Iraq to end Kingdom, USA Saddam Hussein’s rule as part of the war on terrorism?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 8-9/02 Gallup “Would you favor or oppose sending Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, American ground troops (the United States USA sending ground troops) to the Persian Gulf in an attempt to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 9/02 Dagsavisen “The USA is threatening to launch a military Norway attack on Iraq. Do you consider it appropriate of the USA to attack [WITHOUT/WITH] the approval of the UN?” (Figures represent average across the two versions of the UN approval question wording responding “under no circumstances”) 1/03 Gallup “Are you in favor of military action against Albania, Argentina, Australia, Iraq: under no circumstances; only if Bolivia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, sanctioned by the United Nations; Cameroon, Canada, Columbia, unilaterally by America and its allies?” Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, (Figures represent percent responding “under Finland, France, Georgia, no circumstances”) Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, Kenya, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Uganda, United Kingdom, USA, Uruguay 1/03 CVVM “Would you support a war against Iraq?” Czech Republic (Figures represent percent responding “no”) 1/03 Gallup “Would you personally agree with or oppose Hungary a US military attack on Iraq without UN approval?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 2 1/03 EOS-Gallup “For each of the following propositions tell Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, me if you agree or not. -

Tabloid Media Campaigns and Public Opinion: Quasi-Experimental Evidence on Euroscepticism in England

Tabloid media campaigns and public opinion: Quasi-experimental evidence on Euroscepticism in England Florian Foos London School of Economics & Political Science Daniel Bischof University of Zurich March 3, 2021 Abstract Whether powerful media outlets have eects on public opinion has been at the heart of theoret- ical and empirical discussions about the media’s role in political life. Yet, the eects of media campaigns are dicult to study because citizens self-select into media consumption. Using a quasi-experiment – the 30-years boycott of the most important Eurosceptic tabloid newspaper, The Sun, in Merseyside caused by the Hillsborough soccer disaster – we identify the eects of The Sun boycott on attitudes towards leaving the EU. Dierence-in-dierences designs using public opinion data spanning three decades, supplemented by referendum results, show that the boycott caused EU attitudes to become more positive in treated areas. This eect is driven by cohorts socialised under the boycott, and by working class voters who stopped reading The Sun. Our findings have implications for our understanding of public opinion, media influence, and ways to counter such influence, in contemporary democracies. abstract=150 words; full manuscript (excluding abstract)=11,915 words. corresponding author: Florian Foos, [email protected]. Assistant Professor in Political Behaviour, Department of Govern- ment, London School of Economics & Political Science. Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, UK. Phone: +44 (0)7491976187. Daniel Bischof, SNF Ambizione Grant Holder, Department of Political Science, University of Zurich. Aolternstrasse 56, 8050 Zurich, CH. Phone: +41 (0)44 634 58 50. Both authors contributed equally to this paper; the order of the authors’ names reflects the principle of rotation. -

After Somerset: the Scottish Experience', Journal of Legal History, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer After Somerset Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 2012, 'After Somerset: The Scottish Experience', Journal of Legal History, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 291-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01440365.2012.730248 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/01440365.2012.730248 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Legal History Publisher Rights Statement: © Cairns, J. (2012). After Somerset: The Scottish Experience. Journal of Legal History, 33(3), 291-312. 10.1080/01440365.2012.730248 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 After Somerset: The Scottish Experience JOHN W. CAIRNS The Scottish evidence examined here demonstrates the power of the popular understanding that, in Somerset’s Case (1772), Lord Mansfield had freed the slaves, and shows how the rapid spread of this view through newspapers, magazines, and more personal communications, encouraged those held as slaves in Scotland to believe that Lord Mansfield had freed them - at least if they reached England. -

Download Free to View British Library Newspapers List 9 August 2021

Free to view online newspapers 9 August 2021 Below is a complete listing of all newspaper titles on the British Library’s initial ‘free to view’ list of one million pages, including changes of title. Start and end dates are for what is being made freely available, not necessarily the complete run of the newspaper. For a few titles there are some missing issues for the dates given. All titles are available via https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. The Age (1825-1843) Alston Herald, and East Cumberland Advertiser (1875-1879) The Argus, or, Broad-sheet of the Empire (1839-1843) The Atherstone Times (1879-1879), The Atherstone, Nuneaton, and Warwickshire Times (1879-1879) Baldwin's London Weekly Journal (1803-1836) The Barbadian (1822-1861) Barbados Mercury (1783-1789), Barbados Mercury, and Bridge-town Gazette (1807-1848) The Barrow Herald and Furness Advertiser (1863-1879) The Beacon (Edinburgh) (1821-1821) The Beacon (London) (1822-1822) The Bee-Hive (1862-1870), The Penny Bee-Hive (1870-1870), The Bee-Hive (1870-1876), Industrial Review, Social and Political (1877-1878) The Birkenhead News and Wirral General Advertiser (1878-1879) The Blackpool Herald (1874-1879) Blandford, Wimborne and Poole Telegram (1874-1879), The Blandford and Wimbourne Telegram (1879-1879) Bridlington and Quay Gazette (1877-1877) Bridport, Beaminster, and Lyme Regis Telegram and Dorset, Somerset, and Devon Advertiser (1865, 1877-1879) Brighouse & Rastrick Gazette (1879-1879) The Brighton Patriot, and Lewes Free Press (1835-1836), Brighton Patriot and South of -

December 4, 2017 the Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washi

December 4, 2017 The Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20230 Re: Uncoated Groundwood Paper from Canada, Inv. Nos. C–122–862 and A-122-861 Dear Secretary Ross: On behalf of the thousands of employees working at the more than 1,100 newspapers that we publish in cities and towns across the United States, we urge you to heavily scrutinize the antidumping and countervailing duty petitions filed by North Pacific Paper Company (NORPAC) regarding uncoated groundwood paper from Canada, the paper used in newspaper production. We believe that these cases do not warrant the imposition of duties, which would have a very severe impact on our industry and many communities across the United States. NORPAC’s petitions are based on incorrect assessments of a changing market, and appear to be driven by the short-term investment strategies of the company’s hedge fund owners. The stated objectives of the petitions are flatly inconsistent with the views of the broader paper industry in the United States. The print newspaper industry has experienced an unprecedented decline for more than a decade as readers switch to digital media. Print subscriptions have declined more than 30 percent in the last ten years. Although newspapers have successfully increased digital readership, online advertising has proven to be much less lucrative than print advertising. As a result, newspapers have struggled to replace print revenue with online revenue, and print advertising continues to be the primary revenue source for local journalism. If Canadian imports of uncoated groundwood paper are subject to duties, prices in the whole newsprint market will be shocked and our supply chains will suffer. -

Albuquerque Evening Citizen, 01-15-1907 Hughes & Mccreight

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 1-15-1907 Albuquerque Evening Citizen, 01-15-1907 Hughes & McCreight Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news Recommended Citation Hughes & McCreight. "Albuquerque Evening Citizen, 01-15-1907." (1907). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news/ 3493 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. pl 1 Th Evening Cltlzan, In Advance, IS per yr. 1 VOL. 21. NO. 13. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, TUESDAY EVENING. JANUARY 15. 1907. Delivered by Carrier, 0 cent pr month. WALL STREET'S RAILROAD SPHINX A PASSENGER THE HOUSE IE0 LA FRANCIS III AND FREIGHT on WORK OF SEV MEXICO GETS rip THE KILLED THE ERALSTATES A VERY W R Usual Way And Head bn Col- Senate Ship Subsidy Bill By Colorado Elects Guggenheim Welcome From President lision Is the Fatal Vote of Eight to Seven to Senate as Patterson's Dlaz-narc- hist Plot Result. Today. Successor. In Spain. RUSH OF PASSENGERS CORTELYOU AND GARFIELD mmm: BAILEY'S FRIENDS SAY BOUNDARY FIXED BETWEEN INJURE GIRL FATALLY REPORTED BY COMMITTEE THEY HAVE WHIPHANDLE Reported De fire Consumes Half Million Dol- Spooner Defends Power ofvPrcs Browne From Nebraska. Richard Kingston Jamlca. lars Worth of Chicago Prop- Ident in Brownsvill son Form Delaware. Elected stroyed by Earthquake. With erty In Few Hours.