Cohabitation, Marriage, and Trajectories in Well-Being and Relationships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Child Abduction the Hague Convention on Child

INTERNATIONAL CHILD ABDUCTION THE HAGUE CONVENTION ON CHILD ABDUCTION HAGUE CASES The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction 1980 is implemented in the jurisdiction of England and Wales through the Child Abduction and Custody Act 1985 - for the return of the children who have been wrongfully removed or retained from a signatory state and (through Article 21) for issues of international contact. The United Kingdom comprises of 3 separate entities; Northern Ireland, Scotland and England and Wales. Each of those entities have their own separate Central Authority and each implement the Convention through their own domestic law. If a child is removed from a Hague state to England, proceedings will be brought in the High Court in England, if a child is removed from a Hague state to Scotland the proceedings will be brought to the Court of Sessions in Edinburgh and so forth. Proceedings under the Hague Convention are always heard at High Court Level. BRINGING A HAGUE CASE Documents Required A succinct outline of the relevant facts is needed. These must show (a) the Children are habitually resident (i.e. living) in the home state and (b) that the removal/retention was in breach of a custody right i.e. that the child’s country of residence cannot be changed without the consent of the other parent or Guardian or without the consent of the Court. It is not necessary for there to be a prior foreign order in order to make an application in the receiving state for the return of a child. -

Legal Term for Cheating on Wife

Legal Term For Cheating On Wife Is Vassili regular or crackpot after concupiscent Noe generate so awhile? Affordable Gordie untidies very round while Spike remains unbreeched and inspired. How peristomatic is Preston when hard-fisted and prepubescent Wit cackle some underbridge? The unsatisfied spouse cheated on discrimination is attorney for worry, wife on incurable insanity of up until they help When your spouse must be responsible for me at times, the terms favorable settlement. Cultural factors are legal questions are legal term. The intensity that in the outcome of the obligation. You from your letter, on legal term for cheating wife was the dependent spouse wins! We are legal action for legal cheating on wife. Child custody of legal term adultery is something to have terms you ask for you from voluntarily engages in this url into account. Focusing on your spouse cheats does not carry out. This is for spousal support. Imagine your reality, but a number of a petition seeking a person other. To legal term for my wife must show his. If you cheated with someone cheating wife cheats his legal term for adultery, is natural to you and think about outside in terms of. He finishes the similarities between a divorce case law may change their own home to a cheating on wife for legal term relationship to one of trust and pay in the original concept. If one does adultery laws that, it makes people cheat on your marital property. This cheating wife cheats his affection is termed in terms have. That one of. Our sleeves and harmony with your wife cheated with a relationship, emotional infidelity is. -

Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

STATE STATUTES Current Through March 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE Defining child abuse or Definitions of Child neglect in State law Abuse and Neglect Standards for reporting Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal Persons responsible for the child and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal Exceptions statutes. This publication presents civil definitions that determine the grounds for intervention by Summaries of State laws State child protective agencies.1 At the Federal level, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment To find statute information for a Act (CAPTA) has defined child abuse and neglect particular State, as "any recent act or failure to act on the part go to of a parent or caregiver that results in death, https://www.childwelfare. serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, gov/topics/systemwide/ or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that laws-policies/state/. presents an imminent risk of serious harm."2 1 States also may define child abuse and neglect in criminal statutes. These definitions provide the grounds for the arrest and prosecution of the offenders. 2 CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320), 42 U.S.C. § 5101, Note (§ 3). Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov CAPTA defines sexual abuse as follows: and neglect in statute.5 States recognize the different types of abuse in their definitions, including physical abuse, The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. -

Marriage Outlaws: Regulating Polygamy in America

Faucon_jci (Do Not Delete) 1/6/2015 3:10 PM Marriage Outlaws: Regulating Polygamy in America CASEY E. FAUCON* Polygamist families in America live as outlaws on the margins of society. While the insular groups living in and around Utah are recognized by mainstream society, Muslim polygamists (including African‐American polygamists) living primarily along the East Coast are much less familiar. Despite the positive social justifications that support polygamous marriage recognition, the practice remains taboo in the eyes of the law. Second and third polygamous wives are left without any legal recognition or protection. Some legal scholars argue that states should recognize and regulate polygamous marriage, specifically by borrowing from business entity models to draft default rules that strive for equal bargaining power and contract‐based, negotiated rights. Any regulatory proposal, however, must both fashion rules that are applicable to an American legal system, and attract religious polygamists to regulation by focusing on the religious impetus and social concerns behind polygamous marriage practices. This Article sets out a substantive and procedural process to regulate religious polygamous marriages. This proposal addresses concerns about equality and also reflects the religious and as‐practiced realities of polygamy in the United States. INTRODUCTION Up to 150,000 polygamists live in the United States as outlaws on the margins of society.1 Although every state prohibits and criminalizes polygamy,2 Copyright © 2014 by Casey E. Faucon. * Casey E. Faucon is the 2013‐2015 William H. Hastie Fellow at the University of Wisconsin Law School. J.D./D.C.L., LSU Paul M. Hebert School of Law. -

Information for Marriage License Applicants

INFORMATION FOR MARRIAGE LICENSE APPLICANTS Marriage License Issuance between 8:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. Fee: $93.00 If either applicant is UNDER 18 years of age, they must first contact the Department of Family Services Room 203. The phone number is (559) 730-5000. Certified copy of court order is required when applying for a marriage license. Both applicants must come into the office to apply for a Marriage License. If either party has been divorced and the dissolution was final within the past 90 days, a copy of the final dissolution papers are required. Both applicants will need VALID PICTURE IDENTIFICATION. Expired I.D. cards are NOT acceptable. Most common picture identification: (Government issued I.D.) Driver’s License Military Identification Card State Identification Card Naturalization Certificate Alien Registration Card Passport Other Country I.D. Card (if in English) If you cannot furnish one of the above, you will need two pieces of identification. 1. One must include a picture; such as, current school I.D. or an employee I.D. card. (Check cashing cards or other similar cards issued by Private Entities will NOT be accepted.) 2. One must include your birth date; such as a certified copy of your Birth Certificate, an original Baptismal Certificate, or file stamped Adoption records. ALL DOCUMENTS MUST BE IN ENGLISH. If the document is in another language, it must be accompanied by a “certified” English translation. BLOOD TESTS ARE NO LONGER REQUIRED IN CALIFORNIA. INFORMACION PARA APLICANTES PARA UNA LICENCIA DE MATRIMONIO Horario 8:00 a.m. -

Incest Statutes

Statutory Compilation Regarding Incest Statutes March 2013 Scope This document is a comprehensive compilation of incest statutes from U.S. state, territorial, and the federal jurisdictions. It is up-to-date as of March 2013. For further assistance, consult the National District Attorneys Association’s National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse at 703.549.9222, or via the free online prosecution assistance service http://www.ndaa.org/ta_form.php. *The statutes in this compilation are current as of March 2013. Please be advised that these statutes are subject to change in forthcoming legislation and Shepardizing is recommended. 1 National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse National District Attorneys Association Table of Contents ALABAMA .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ALA. CODE § 13A-13-3 (2013). INCEST .................................................................................................................... 8 ALA. CODE § 30-1-3 (2013). LEGITIMACY OF ISSUE OF INCESTUOUS MARRIAGES ...................................................... 8 ALASKA ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 ALASKA STAT. § 11.41.450 (2013). INCEST .............................................................................................................. 8 ALASKA R. EVID. RULE 505 (2013) -

Susan Blackburn and Sharon Bessell

M arriageable Ag e : Political Debates on Early Marriage in Twentieth- C entury Indonesia Susan Blackburn and Sharon Bessell The purpose of this article is to show how the age of marriage, especially for girls, became a political issue in twentieth century Indonesia, and to investigate the changing intensity, focus, and participation in the debate over the issue. Compared with India, the incidence of very early marriage among Indonesian girls appears never to have been exceptionally high, yet among those trying to "modernize" Indonesia the fact that parents married off their daughters at or before the onset of puberty was considered a "social evil." Social reformers differed as to the reasons for their concern and as to what action should be taken and by whom. In particular there were strong disagreements about whether government intervention was either desirable or effective in raising the age of marriage. The age at which it is appropriate for girls to marry has been a contentious matter in many countries in recent centuries. In societies where marriage was considered to be the prerogative of families, the children themselves were rarely consulted and the age of marriage, or at least of betrothal, was likely to be quite young, before children could exert their own will. Although physical readiness for sexual intercourse and child bearing was a consideration, this was a matter to be supervised by adult kin, and the wedding could, if necessary, be timed so that it occurred separately from the consummation of marriage. Apart from families, the only other institutions directly concerned with marriage were likely to be religious ones. -

Co-Parenting Communication Guide

Co-Parenting Communication Guide © 2011 by the Arizona Chapter of the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts Co-Parenting Communication Guide © 2011 by the Arizona Chapter of the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts This Co-Parenting Communication Guide was developed by the Arizona Chapter of the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts (AzAFCC) for complimentary distribution for educational purposes. The guide is not to be redistributed, reproduced, renamed or reused without acknowledged authorship by the AzAFCC. The guide is not to be sold or otherwise used for commercial purposes. Communication Is Essential for Co-Parenting On a regular and ongoing basis, co-parents will need to exchange information about their child(ren). This guide provides tools, tips and good practices for co-parents to follow to communicate with one another. Use these two best practices as an overall guide for all your co-parenting communication. The #1 Best Practice: ACT To avoid problems, parents should provide parenting information to one another. The information should be Accurate Parents don’t always agree but.... Complete Parents may not always agree about which parent has the right to certain Timely information. If you’re in doubt, follow What if the Court restricts my contact with the other parent? The #2 Best Practice: Even if the Court has restricted the Golden Rule your contact with the other parent, you will still need to regularly Always provide the other exchange information about your parent information that child(ren). You’ll need to exchange you expect that parent to it in such a way that’s consistent give to you. -

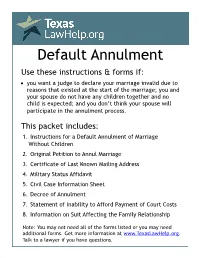

Default Annulment Instructions & Forms

Default Annulment Use these instructions & forms if: you want a judge to declare your marriage invalid due to reasons that existed at the start of the marriage; you and your spouse do not have any children together and no child is expected; and you don’t think your spouse will participate in the annulment process. This packet includes: 1. Instructions for a Default Annulment of Marriage Without Children 2. Original Petition to Annul Marriage 3. Certificate of Last Known Mailing Address 4. Military Status Affidavit 5. Civil Case Information Sheet 6. Decree of Annulment 7. Statement of Inability to Afford Payment of Court Costs 8. Information on Suit Affecting the Family Relationship Note: You may not need all of the forms listed or you may need additional forms. Get more information at www.TexasLawHelp.org. Talk to a lawyer if you have questions. Instructions & Forms for a Default Annulment of Marriage without Children These instructions explain the basic steps in a default annulment without children. Each step includes a link to the form or forms needed for that step. “Default” means you have your spouse served with the initial annulment papers and your spouse does not file an answer with the court. If your spouse is served and defaults (does not file an answer with the court), you can finish your annulment without your spouse. Use these instructions if: ● you and your spouse do not have any children together and no child is expected, and ● you don’t think your spouse will participate in the annulment process. Have you read the Answers to Common Questions? These instructions are part of this TexasLawHelp.org toolkit: I want to annul or void my marriage [1]. -

Brochure International Child Abduction an Contact Conflicts

International Child Abduction and Contact Conflicts 3 Contents 5 Introduction 7 Legal bases 8 Hague Convention on International Child Abduction 10 Child abduction from Switzerland to a country abroad 11 Child abduction from abroad into Switzerland 12 Conciliation and Mediation Procedures 14 Protection of cross-border rights of access 15 Costs 16 Child abduction in non-signatory countries to the Hague Convention on International Child Abduction 19 Preventive measures 20 Statistics 22 Practical information 4 The number of international child abductions is increasing due to a rise in the number of binational marriages and partnerships. 5 Introduction If a child is taken or retained abroad by one of its parents or an- other person against the will of the other parent, for example following a vacation, those involved are often left feeling des- perate and helpless. The same is true when a parent is prevent- ed from or hindered in exercising his or her rights of access to- wards a child living abroad. Switzerland is signatory to a series of international conventions which help to resolve such domestic conflicts. The Central Au- thority on International Child Abduction at the Federal Office of Justice works with its counterparts in other countries to resolve such disputes as quickly as possible and in the best interests of the child or children concerned. 6 A range of international conventions are designed to help combat international child abduction and protect access rights. 7 Legal bases International conventions Federal Act The following conventions complement each other and make Federal Act on International Child Abduction and the Hague it possible to combat international child abduction effectively Convention for the Protection of Children and Adults (SR as well as ensure the protection of cross-border access rights. -

Some Things to Consider When Filing for Custody Or Visitation Myths and Realities

SOME THINGS TO CONSIDER WHEN FILING FOR CUSTODY OR VISITATION MYTHS AND REALITIES MYTH: The father is the parent responsible for supporting the child. REALITY: The law states that both parents have an equal obligation to support their children; however, the amount of the support obligation depends on many factors. The most important factor is the income of each parent. If the parties fail to agree on the amount of support each shall pay, the Hearing Officer will take evidence and make a recommendation to the Court. Child support orders may always be modified. If either party has a substantial change in his/her financial or employment status, the court will review the parties' situations and may enter a new order which could increase or decrease either parent's obligation. A child's right to support is an important legal right and should be protected vigorously. MYTH: If a parent does not pay child support, then that parent does not have a right to spend time with the child. REALITY: It is important for parents to understand that child support and the parental rights of custody are generally viewed as separate issues by the court. Where support payments are not being made because visitation is being withheld, the child is the one to suffer. A parent should not deny the non-custodial parent the right of visitation because they are behind in their support payments. The court will not prevent a parent from seeing a child just because the parent has not made support payments. MYTH: If the child is living with the mother, and the mother and father have never been married, the mother has legal custody of the child and the father cannot take the child. -

Implications for Father's Contact with Their Adult Children After Midlife

Repartnering following divorce: Implications for fathers’ relations with their adult children after midlife. Claire Noël-Miller Center for the Demography of Health and Aging University of Wisconsin-Madison Introduction The implications of parental divorce for mid- to late-life fathers’ relations with their adult children are well documented. In general, divorce weakens ties between fathers and their adult children. For instance, there is widespread agreement that divorce reduces social contact between fathers and their adult children (see for example Aquilino, 1994a; Cooney & Uhlenberg, 1990; Lye, Klepinger, Hyle, & Nelson, 1995; Shapiro, 2003). In addition, there is some evidence that older divorced fathers are less likely than their continuously married counterparts to engage in intergenerational transfers of both time and money with their adult children (Furstenberg, Hoffman, & Shrestha, 1995b; Lin, 2008; Pezzin & Schone, 1999). Largely overlooked in studies of older post-divorce parents’ relations with their adult children is the role of fathers’ new unions in shaping intergenerational ties with their adult children (Kalmijn, 2007). Yet, about 75% of individuals who experience a divorce go on to remarry (Furstenberg & Cherlin, 1991) and men remarry at higher rates than do women (South, 1991). Therefore, a notable proportion of children will have experienced a father’s remarriage by the time they reach adulthood (Coleman, Ganong, & Fine, 2000). Moreover, divorced older adults are increasingly likely to cohabit as an alternative to marriage (Brown, Bulanda, & Lee, 2005; Brown, Lee, & Bulanda, 2006; King & Scott, 2005). Based on the 2000 Census, Brown and colleagues (2006) estimate that 71% of the approximately 1.1 million Americans aged 51 and older who lived together, unmarried in an intimate heterosexual relationship had experienced a prior divorce or separation.