The Sound of Ethnic America: Prewar “Foreign-Language” Recordings & the Sonics of Us Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polka Sax Man More Salute to Steel 3 from the TPN Archives Donnie Wavra July 2006: 40Th National Polka by Gary E

Texas Polka News - March 2016 Volume 28 | Isssue 2 INSIDE Texas Polka News THIS ISSUE 2 Bohemian Princess Diary Theresa Cernoch Parker IPA fundraiser was mega success! Welcome new advertiser Janak's Country Market. Our first Spring/ Summer Fest Guide 3 Editor’s Log Gary E. McKee Polka Sax Man More Salute to Steel 3 From the TPN Archives Donnie Wavra July 2006: 40th National Polka By Gary E. McKee Festival Story on Page 4 4-5 Featured Story Polka Sax Man 6-7 Czech Folk Songs Program; Ode to the Songwriter 8-9 Steel Story Continued 10 Festival & Dance Notes 12-15 Dances, Festivals, Events, Live Music 16-17 News PoLK of A Report, Mike's Texas Polkas Update, Czech Heritage Tours Special Trip, Alex Says #Pep It Up 18-19 IPA Fundraiser Photos 20 In Memoriam 21 More Event Photos! 22-23 More Festival & Dance Notes 24 Polka Smiles Sponsored by Hruska's Spring/SummerLook for the Fest 1st Annual Guide Page 2 Texas Polka News - March 2016 polkabeat.com Polka On Store to order Bohemian Princess yours today!) Texas Polka News Staff Earline Okruhlik and Michael Diary Visoski also helped with set up, Theresa Cernoch Parker, Publisher checked people in, and did whatever Gary E. McKee, Editor/Photo Journalist was asked of them. Valina Polka was Jeff Brosch, Artist/Graphic Designer Contributors: effervescent as always helping decorate the tables and serving as a great hostess Julie Ardery Mark Hiebert Alec Seegers Louise Barcak Julie Matus Will Seegers leading people to their tables. Vernell Bill Bishop Earline Berger Okruhlik Karen Williams Foyt, the Entertainment Chairperson Lauren Haase John Roberts at Lodge 88, helped with ticket sales. -

“Folk Music in the Melting Pot” at the Sheldon Concert Hall

Education Program Handbook for Teachers WELCOME We look forward to welcoming you and your students to the Sheldon Concert Hall for one of our Education Programs. We hope that the perfect acoustics and intimacy of the hall will make this an important and memorable experience. ARRIVAL AND PARKING We urge you to arrive at The Sheldon Concert Hall 15 to 30 minutes prior to the program. This will allow you to be seated in time for the performance and will allow a little extra time in case you encounter traffic on the way. Seating will be on a first come-first serve basis as schools arrive. To accommodate school schedules, we will start on time. The Sheldon is located at 3648 Washington Boulevard, just around the corner from the Fox Theatre. Parking is free for school buses and cars and will be available on Washington near The Sheldon. Please enter by the steps leading up to the concert hall front door. If you have a disabled student, please call The Sheldon (314-533-9900) to make arrangement to use our street level entrance and elevator to the concert hall. CONCERT MANNERS Please coach your students on good concert manners before coming to The Sheldon Concert Hall. Good audiences love to listen to music and they love to show their appreciation with applause, usually at the end of an entire piece and occasionally after a good solo by one of the musicians. Urge your students to take in and enjoy the great music being performed. Food and drink are prohibited in The Sheldon Concert Hall. -

Dzovig Markarian

It is curious to notice that most of Mr. Dellalian’s writings for piano use aleatoric notation, next to extended techniques, to present an idea which is intended to be repeated a number of times before transitioning to the next. The 2005 compilation called “Sounds of Devotion,” where the composer’s family generously present articles, photos and other significant testimony on the composer’s creative life, remembers the two major influences in his music to be modernism and the Armenian Genocide. GUEST ARTIST SERIES ABOUT DZOVIG MARKARIAN Dzovig Markarian is a contemporary classical pianist, whose performances have been described in the press as “brilliant” (M. Swed, LA Times), and “deeply moving, technically accomplished, spiritually uplifting” (B. Adams, Dilijan Blog). An active soloist as well as a collaborative artist, Dzovig is a frequent guest with various ensembles and organizations such as the Dilijan Chamber Music Series, Jacaranda Music at the Edge, International Clarinet Conference, Festival of Microtonal Music, CalArts Chamber Orchestra, inauthentica ensemble, ensemble Green, Xtet New Music Group, USC Contemporary Music Ensemble, REDCAT Festivals of Contemporary Music, as well as with members of the LA PHIL, LACO, DZOVIG MARKARIAN Southwest Chamber Music, and others. Most recently, Dzovig has worked with and premiered works by various composers such as Sofia Gubaidulina, Chinary Ung, Iannis Xenakis, James Gardner, Victoria Bond, Tigran Mansurian, Artur Avanesov, Jeffrey Holmes, Alan Shockley, Adrian Pertout, Laura Kramer and Juan Pablo Contreras. PIANO Ms. Markarian is the founding pianist of Trio Terroir, a Los Angeles based contemporary piano trio devoted to new and complex music from around the world. -

Mountains Book 5.Ppp

Far in the Mountains Volume 5 - Echoes from the Mountains Since their publication, back in 2002, the 4-CD set Far in the Mountains have been MT's best-selling production and they are a wonderful source of splendid songs, tunes and stories. So it is with great pleasure that I announce the publication of Far in the Mountains, volume 5. Mike Yates writes: Once these [four CDs] were issued, I set the original recordings aside and got on with a number of other projects. Over the years my interests began to change and I found myself devoting more time to art ... But the Appalachians were still there, in the back of my mind. Recently I found time to re-listen to some of the recordings that had not made their way onto the four CDs, and I was rather surprised to discover just how much good material had been left off the albums, and so I set about putting together Far in the Mountains - Volume 5. I am sure that many of the 425 people who bought the original 4-CD Set will want to add Volume 5 to their record collections ... in the current economic climate, I really hope so! And maybe a few others will remember that they had always wanted to buy them - but never got round to it. William Marshall & Howard Hall: Charlie Woods: 1.Train on the Island 1:15 22. Cindy 1:29 2. Polly Put the Kettle On 1:11 23. Eighth of January / Green Mountain 2:14 3. Fortune 1:13 Polka 24. -

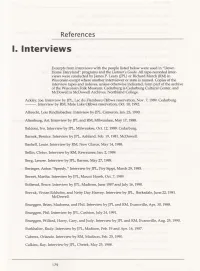

I. Interviews

References I. Interviews Excerpts from interviews with the people listed below were used in "Down Home Dairyland" programs and the Listener's Guide. All tape-recorded inter views were conducted by James P. Leary (JPL) or Richard March (RM) in Wisconsin except where another interviewer or state is named. Copies of the interview tapes and indexes, unless otherwise indicated, form part of the archive of the Wisconsin Folk Museum. Cedarburg is Cedarburg Cultural Center, and McDowell is McDowell Archives, Northland College . Ackley, Joe. Interview by JPL, Lac du Flambeau Ojibwa reservation, Nov. 7, 1989. Cedarburg. ---. Interview by RM, Mole Lake Ojibwa reservation, Oct. 10, 1992. Albrecht, Lois Rindlisbacher. Interview by JPL, Cameron, Jan. 23, 1990. Altenburg, Art. Interview by JPL and RM, Milwaukee, May 17, 1988. Baldoni, Ivo. Interview by JPL, Milwaukee, Oct. 12, 1989. Cedarburg. Barnak, Bernice. Interview by JPL, Ashland, Feb. 19, 1981. McDowell. Bashell, Louie. Interview by RM, New Glarus, May 14, 1988. Bellin, Cletus. Interview by RM, Kewaunee, Jan. 2, 1989. Berg, Lenore. Interview by JPL, Barron, May 27, 1989. Beringer, Anton "Speedy." Interview by JPL, Poy Sippi, March 29, 1985. Bernet, Martha . Interview by JPL, Mount Horeb, Oct. 7, 1989. Hollerud, Bruce. Interview by JPL, Madison, June 1987 and July 16, 1990. Brevak, Vivian Eckholm, and Netty Day Harvey. Interview by JPL, Barksdale, June 22, 1981. McDowell. Brueggen, Brian, Madonna, and Phil. Interview by JPL and RM, Evansville, Apr. 30, 1988. Brueggen, Phil. Interview by JPL, Cashton, July 24, 1991. Brueggen, Willard, Harry, Gary, and Judy. Interview by JPL and RM, Evansville, Aug. 25, 1990. -

IRCA FOREIGN LOG 10Th Edition +Hrd Again W/Light Inst Mx at 0456 on 1/4

IRCA FOREIGN LOG 10th Edition +Hrd again w/light Inst mx at 0456 on 1/4. Poorer than before. (PM-OR) DX World Wide – West +NRK 0244 12/29 country music occasionally coming thru clearly in domestic TRANS-ATLANTIC DX ROUNDUP slop (I've logged & QSLed this one with this early Mon morning country-music show before). First time I've had audio from this one all season. [Stewart-MO] 162 FRANCE , Allouis, 0230 3/7. Male DJ hosting a program of mainly EE pop +2/15 0503 Poor to fair signals in NN talk and oldies mx. Only TA on the MW songs. Fair signal, but much weaker than Iceland. (NP-AB) band. (VAL-DX) +0406 4/18, pop song in FF. (NP-AB*) 1467 FRANCE , Romoules TRW, 12/27 2309 Fair signals peaking w/good Choraol 189 ICELAND , Guguskalar Rikisutvarpid, 2/15 0032. Fair signals with Icelandic mx and rel mx. Het on this one was huge! New station and new Country on talk and a mix of mx some in EE. Only LW station to produce audio. MW. (SA-MB) (VAL-DX) 1512 SAUDI ARABIA , Jeddah BSKSA, 12/27 2248 poor signals w/AA mx and talk. +0227 3/7. Very good signal w/EE lang R&B pop/rock songs hosted by man in New station. (SA-MB) what I presumed was Icelandic. Ranks up there as the best signal I've hrd +12/29 seemed to sign on right at 0300 with no announcements, int signal, from them. (NP-AB) anthem, or anything, just Koranic chanting. -

Blues in the 21St Century

Blues in the 21 st Century Myth, Self-Expression and Trans-Culturalism Edited by Douglas Mark Ponton University of Catania, Italy and Uwe Zagratzki University of Szczecin, Poland Series in Music Copyright © 2020 by the Authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Music Library of Congress Control Number: 2019951782 ISBN: 978-1-62273-634-8 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Jean-Charles Khalifa. Cover font (main title): Free font by Tup Wanders. Table of contents List of Figures vii List of Tables ix Preface xi Acknowledgements xix Part One: Blues impressions: responding to the music 1 1. -

Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': the Johnson City Sessions Ted Olson East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 2013 'Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': The Johnson City Sessions Ted Olson East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Citation Information Olson, Ted. 2013. 'Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': The oJ hnson City Sessions. The Old-Time Herald. Vol.13(6). 10-17. http://www.oldtimeherald.org/archive/back_issues/volume-13/13-6/johnsoncity.html ISSN: 1040-3582 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music?': The ohnsonJ City Sessions Copyright Statement © Ted Olson This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/1218 «'CAN YOU SING OR PLAY OLD-TIME MUSIC?" THE JOHNSON CITY SESSIONS By Ted Olson n a recent interview, musician Wynton Marsalis said, "I can't tell The idea of transporting recording you how many times I've suggested to musicians to get The Bristol equipment to Appalachia was, to record Sessions—Anglo-American folk music. It's a lot of different types of companies, a shift from their previous music: Appalachian, country, hillbilly. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

16 Artist Index BILLJ~OYD (Cont'd) Artist Index 17 MILTON BROWN

16 Artist Index Artist Index 17 BILLJ~OYD (cont'd) MILTON BROWN (cont'd) Bb 33-0501-B 071185-1 Jennie Lou (Bill Boyd-J.C. Case)-1 82800-1 071186-1 Tumble Weed Trail (featured in PRC film "Tumble Do The Hula Lou (Dan Parker)-1 Bb B-5485-A, Weed Trail") (Bill Boyd-Dick Reynolds)-1 Bb B-9014-A MW M-4539-A, 071187-1 Put Your Troubles Down The Hatch (Bill Boyd• 82801-1 M-4756-A Marvin Montgomery) -3 Bb 33-0501-A Garbage Man Blues (Dan Parker) -1,3 Bb B-5558-B, 071188-1 Home Coming Waltz Bb B-890Q-A, 82802-1 MWM-4759-A RCA 2Q-2069-A Four, Five Or Six Times (Dan Parker) -1,3* Bb B-5485-B, 071189-1 Over The Waves Waltz (J. Rosas) Bb B-8900-B, MW M-4539-B, RCA 2Q-2068-B M-4756-B Reverse of RCA 2Q-2069 is post-war Bill Boyd title. First pressings of Bb B-5444 were issued as by The Fort Worth Boys with "Milton Brown & his Musical Brownies" in parentheses. On this issue, co-writer for "Oh You Pretty Woman" is listed as Joe Davis. 1937 issues of 82801 ("staff' Bluebird design) list title as "Garage Man Blues." JIM BOYD & AUDREY DAVIS (The Kansas Hill Billies) September 30, 1934; Fort Worth, Texas August 8, 1934; Texas Hotel, San Antonio, Texas. Jim Boyd, guitarllead vocal; Audrey Davis, fiddle/harmony vocal. Milton Brown, vocal-1; Cecil Brower, fiddle; Derwood Brown, guitar/vocal-2; Fred "Papa" Calhoun, piano; Wanna Coffman, bass; Ted Grantham, fiddle; Ocie Stockard, tenor banjo; Band backing vocal -3. -

Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection

Search artists, albums and more... ' Explore + Marketplace + Community + * ) + Dashboard Collection Wantlist Lists Submissions Drafts Export Settings Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection Collection Value:* Min $3,698.90 Med $9,882.74 Max $29,014.80 Sort Artist A-Z Folder Keepers (500) Show 250 $ % & " Remove Selected Keepers (500) ! Move Selected Artist #, Title, Label, Year, Format Min Median Max Added Rating Notes Johnny Cash - American Recordings $43.37 $61.24 $105.63 over 5 years ago ((((( #366 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release American Recordings, American Recordings 9-45520-1, 1-45520 Near Mint (NM or M-) Shrink 1994 US Johnny Cash - At Folsom Prison $4.50 $29.97 $175.84 over 5 years ago ((((( #88 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Very Good Plus (VG+) US 1st Release Columbia CS 9639 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1968 US Johnny Cash - With His Hot And Blue Guitar $34.99 $139.97 $221.60 about 1 year ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Mic Very Good Plus (VG+) top & spine clear taped Sun (9), Sun (9), Sun (9) 1220, LP-1220, LP 1220 Very Good (VG) 1957 US Joni Mitchell - Blue $4.00 $36.50 $129.95 over 6 years ago ((((( #30 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album, Pit Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release Reprise Records MS 2038 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1971 US Joni Mitchell - Clouds $4.03 $15.49 $106.30 over 2 years ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Ter Near Mint (NM or M-) Reprise Records RS 6341 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1969 US Joni Mitchell - Court And Spark $1.99 $5.98 $19.99