Dream History of the Global South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Perestroika by Vijay Prashad, Professor of International Studies, Trinity College

UNCTAD Public Symposium 24 - 25 June, 2013 New Economic Approaches for a Coherent Post- 2015 Agenda Global Perestroika by Vijay Prashad Professor of International Studies, Trinity College, Hartford Disclaimer Articles posted on the website are made available by the UNCTAD secretariat in the form and language in which they were received and are the sole responsibility of their authors. The views reflected in the articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or UNCTAD. Global Perestroika/Vijay Prashad/UNCTAD Public Symposium. 1 Global Perestroika. Vijay Prashad. UNCTAD Public Symposium, Geneva, June 25, 2013. For R. Krishnamurti, chef de cabinet to Raul Prebisch, UNCTAD. I. UN reports make for dreary reading. UNHCR and UNESCO accounts from Syria colour in the misery of that enduring conflict. Updates from the peacekeepers tell us that no political solution is near the horizon of the Great Lakes of Africa. The ILO documents confound us with percentages of structural unemployment, and its attendant social unrest. The FAO frightens us with data on hunger and food insecurity. Bleak accounts from UN Women tell us that violence against women seems unabated. The ILO’s Ending Child Labour in Domestic Work report from a fortnight ago shows that 15.5 million children under 18 work as domestic labourers. Of them, ten million work in “conditions tantamount to slavery.” These are mainly young girls (73 per cent), who have forfeited their childhood and their education. Good news rarely comes from the UN – the small stories of individuals who ascend from desperate situations are a sliver of silver in a cloud ever darkened by the torments put on them by forces that the UN has not been allowed to identify. -

International Law in the Nigerian Legal System Christian N

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 1997 International Law in the Nigerian Legal System Christian N. Okeke Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation 27 Cal. W. Int'l. L. J. 311 (1997) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE NIGERIAN LEGAL SYSTEM CHRISTIAN N. OKEKE· Table ofContents INTRODUCTION 312 ARGUMENT OF THE PAPER 312 DEFINITIONS 317 I. UNITED NATIONS DECADE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 321 II. HISTORICAL OUTLINE 323 A. Nigeria and Pre-Colonial International Law 323 B. Nigeria and "Colonial" International Law 326 C. The Place ofInternational Law in the Nigerian Constitutional Development 328 III. GENERAL DISPOSITION TOWARD INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE ESTABLISHED RULES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 330 IV. THE PLACE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW IN NIGERIAN MUNICIPAL LAW 335 V. NIGERIA'S TREATY-MAKING PRACTICE , 337 VI. ApPLICABLE LAW IN SELECTED QUESTIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 339 A. International Human Rights and Nigerian Law 339 B. The Attitude ofthe Nigerian Courts to the Decrees and Edicts Derogating from Human Rights ............ 341 c. Implementation ofInternational Human Rights Treaties to Which Nigeria is a Party 342 D. Aliens Law .................................. 344 E. Extradition .................................. 348 F. Extradition and Human Rights 350 VII. -

From the Third World to the Global South Written by Alina Sajed

From the Third World to the Global South Written by Alina Sajed This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. From the Third World to the Global South https://www.e-ir.info/2020/07/27/from-the-third-world-to-the-global-south/ ALINA SAJED, JUL 27 2020 The term ‘Global South’ is not an uncontroversial one. There have been many debates in the last few decades regarding its usefulness, both analytical and historical, but especially its connection to another equally debated term, ‘Third World.’ In the midst of these debates, however, there has appeared a loose consensus around their meaning and their linkages. I will attempt to elucidate here the meaning and histories of both terms, and the connections and ruptures between them. To do so, I will be drawing on the work of several Marxist intellectuals, such as L.S. Stavrianos and Vijay Prashad, among others. It must be emphasized, however, that the term Global South cannot be considered separately from that of the Third World. I argue that the idea of Global South could not have emerged without taking seriously the conceptual work done by the term Third World, and indeed without the legacy left by Third Worldism and its historical landmarks. The discussion below devotes significant space to understanding not only the emergence of the term Third World, but especially the central role played by processes of capitalist expansion to conceptualizing both Third World and Global South, albeit in different ways and at different historical junctures. -

Arab Spring, Libyan Winter Vijay Prashad Remarks

Arab Spring, Libyan Winter Vijay Prashad remarks. Arab Spring, Libyan Winter is less about predicting the future and more about showing us how the Atlantic powers insinuated themselves into the Arab Spring, to attempt to create a Libyan Winter to the advantage of their national interests, the interest of the multinational oil firms and the neoliberal reformers within Libya. Part I: Arab Spring. I. Bread When the unwashed began to assert themselves in France, the royalty scoffed at them. What they wanted was bread, whose price skyrocketed in 1774–75. Taking to the streets in remarkable numbers, the people demanded fair prices for bread, their main staple. In reaction to la guerre des farines, the flour war, Marie Antoinette proposed that the poor “eat cake.” After the Revolution removed the monarchy and its élèves from the thrones of power, the new government hastened to subsidize bread. Hunger broke the back of fear. It is the lesson for the ages. It was a lesson for North Africa in late 2010. In the last two quarters of 2010, the IMF Food Price Index rose by thirty percent. Grain prices soared by sixty percent. Protestors in Tunisia came onto the streets in December with baguettes raised in the air. In Egypt, protestors took to the streets in January chanting, “They are eating pigeon and chicken, and we are eating beans all the time.” Hunger and inequality drove the protests. Their governments hastened to up their subsidies, but it was too little, too late. The question of bread reveals a great deal about the delinquent states in Egypt and Tunisia. -

War Rites and Women's Rights

Smith ScholarWorks Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications Study of Women and Gender Spring 2005 Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth Armstrong Smith College, [email protected] Vijay Prashad Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Elisabeth and Prashad, Vijay, "Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights" (2005). Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs/22 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Author(s): Elisabeth B. Armstrong and Vijay Prashad Source: CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, terror wars (spring 2005), pp. 213- 253 Published by: Michigan State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41949472 Accessed: 14-01-2020 19:07 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Michigan State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to CR: The New Centennial Review This content downloaded from 131.229.19.247 on Tue, 14 Jan 2020 19:07:36 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Solidarity War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth b. -

Introduction 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South

Notes Introduction 1. Kwame Nkrumah, Towards Colonial Freedom: Africa in the Struggle against World Imperialism, London: Heinemann, 1962. Kwame Nkrumah was the first president of Republic of Ghana, 1957–1966. 2. J.M. Roberts, History of the World, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 425. For further details see Leonard Thompson, A History of South Africa, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990, pp. 31–32. 3. Douglas Farah, “Al Qaeda Cash Tied to Diamond Trade,” The Washington Post, November 2, 2001. 4. Ibid. 5. http://www.africapolicy.org/african-initiatives/aafall.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 6. G. Feldman, “U.S.-African Trade Profile.” Also available online at: http:// www.agoa.gov/Resources/TRDPROFL.01.pdf. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 7. Ibid. 8. Salih Booker, “Africa: Thinking Regionally, Update.” Also available online at: htt://www.africapolicy.org/docs98/reg9803.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 9. For full details on Nigeria’s contributions toward eradication of the white minority rule in Southern Africa and the eradication of apartheid system in South Africa see, Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigerian Foreign Policy under Military Rule, 1966–1999, Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003, pp. 79–93. 10. See Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of Zimbabwe: A Study of Foreign Policy Decision Making of an Emerging Nation. Stockholm, Sweden: Bethany Books, 1992, p. 141. 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South Africa 1. “Mr. Prime Minister: A Selection of Speeches Made by the Right Honorable, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa,” Prime Minister of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Lagos: National Press Limited, 1964, p. -

To Be Effective, Socialism Must Adapt to 21St Century Needs

To Be Effective, Socialism Must Adapt To 21st Century Needs Vijay Prashad IS socialism making a comeback? If so, what exactly is socialism, why did it lose steam toward the latter part of the 20th century, and how do we distinguish democratic socialism, currently in an upward trend in the U.S., from social democracy, which has all but collapsed? Vijay Prashad, executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and a leading scholar in socialist studies and the politics of the global South, offers answers to these questions. C.J. Polychroniou: Socialism represented a powerful and viable alternative to capitalism from the mid-1800s all the way up to the third quarter of the 20th century, but entered a period of crisis soon thereafter for reasons that continue to be debated today. In your view, what are some of the main political, economic and ideological factors that help explain socialism’s setback in the contemporary era? Vijay Prashad: The first thing to acknowledge is that “socialism” is not merely a set of ideas or a policy framework or anything like that. Socialism is a political movement, a general way of referring to a situation where the workers gain the upper hand in the class struggle and put in place institutions, policies and social networks that advantage the workers. When the political movement is weak and the workers are on the weaker side of the class struggle, it is impossible to speak confidently of “socialism.” So, we need to study carefully how and why workers — the immense majority of humanity — began to see the reservoirs of their strength get depleted. -

Africa and the OAU Zdenel< Cervenl<A

The Unfinished Quatfor Unity THE UMFIMISHED QUEST FORUMITY Africa and the OAU Zdenel< Cervenl<a JrFRIEDMANN Julian Friedmann Publishers Ltd 4 Perrins Lane, London NW3 1QY in association with The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala, Sweden. THE UNFINISHED QUEST FOR UNITY first published in 1977 Text © Zdenek Cervenka 1977 Typeset by T & R Filmsetters Ltd Printed in Great Britain by ISBN O 904014 28 2 Conditions of sale This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition inc1uding this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction by Raph Uwechue ix Author's Note xiv Map xx CHAPTER l:The Establishment of the Organization of African Unity 1 1. Africa before the OAU 1 2. The Addis Ababa Summit Conference 4 CHAPTER II: The OAU Charter 12 1. The purposes .12 2. The principles .13 3. Membership .16 CHAPTER III: The Principal Organs of the OAU. .. 20 1. The Assembly of Heads of State and Government .20 2. The Council of Ministers .24 3. The General Secretariat .27 4. The Specialized Commissions .36 5. The Defence Commission .38 CHAPTER lY: The OAU Liberation Committee . .45 1. Relations with the liberation movements .46 2. Organization and structure .50 3. Membership ..... .52 4. Reform limiting its powers .55 5. The Accra Declaration on the new liberation strategy .58 6. -

Nigerian History and Current Affairs August 2013 Vol

Nigerian History and Current Affairs August 2013 Vol. 4.0 Origination, Information and Statistics Current Ministers as @ Aug. 2013 Top Officials in Government States Data and Governors Addresses of Federal Ministries Addresses of State Liaison Offices Past and Present Leaders 1960 -2013 Foreign Leaders 1921 - 1960 Natural Resources Tourist Attractions Exchange Rate History Memorable events - 800BC to Aug. 2013 Political Parties Map of Nigeria Compilation Addresses of Federal Ministries by Government Websites www.promong.com Local Government Areas Promoting brands nationwide Tertiary Institutions Important Abbreviations …more than 10,000 monthly Sports Info downloads !!! Traditional Ruler Titles Civil War Events Memorable Dates Brief Biography of Notable Nigerians Web Diary General Knowledge Quiz Downloadable from www.promong.com 2 Contents Nigeria Origination, Information and Statistics………………..…………………………………………………………………………….3 States and Their Natural Resources...................…………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Tourist Attraction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Anthem, Pledge, Coat of Arms and National Flag……………………………………………………………………………………………9 Senate Presidents,Foreign Leaders, Premiers of the 1st Republic…………………………………………………………………..9 Inec Chairmen, Govenors of the 2nd Republic.………………………………………………..……….………………………………….10 Historical value of the Us dollar to the Naira…………………………………………………………….………………………………….10 Civil War Events…………………………………………………………….. ……………………………………….……………………………….…10 Vice Presidents, -

Black Masculinity and Obama's Feminine Side

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2009 Our First Unisex President?: Black Masculinity and Obama's Feminine Side Frank Rudy Cooper University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Gender Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Frank Rudy, "Our First Unisex President?: Black Masculinity and Obama's Feminine Side" (2009). Scholarly Works. 1124. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/1124 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUR FIRST UNISEX PRESIDENT?: BLACK MASCULINITY AND OBAMA'S FEMININE SIDE FRANK RUDY COOPERt ABSTRACT People often talk about the significance of Barack Obama's status as our first black President. During the 2008 Presidential campaign, however, a newspaper columnist declared, "If Bill Clinton was once con- sidered America's first black president, Obama may one day be viewed as our first woman president." That statement epitomized a large media discourse on Obama's femininity. In this essay, I thus ask how Obama will influence people's understandings of the implications of both race and gender. To do so, I explicate and apply insights from the fields of identity performance theory, critical race theory, and masculinities studies. With respect to race, the essay confirms my prior theory of "bipolar black masculinity." That is, the media tends to represent black men as either the completely threatening and race-affirming Bad Black Man or the completely comforting and assimilationist Good Black Man. -

Cataracts of Silence

RACISM Durban, South Africa and PUBLIC 3 - 5 September 2001 POLICY Cataracts of Silence Race on the Edge of Indian Thought Vijay Prashad United Nations Research Institute for Social Development 2 The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multidisciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary problems affecting development. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and environmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of national research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. Current research programmes include: Civil Society and Social Movements; Democracy, Governance and Human Rights; Identities, Conflict and Cohesion; Social Policy and Development; and Technology, Business and Society. A list of the Institute’s free and priced publications can be obtained by contacting the Reference Centre. UNRISD work for the Racism and Public Policy Conference is being carried out with the support of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. UNRISD also thanks the governments of Denmark, Finland, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom for their core funding. UNRISD, Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 9173020 Fax: (41 22) 9170650 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unrisd.org Copyright © UNRISD. This paper has not been edited yet and is not a formal UNRISD publication. -

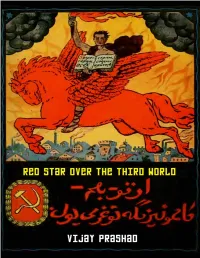

“Red Star Over the Third World” by Vijay Prashad

ALSO BY VIJAY PRASHAD FROM LEFTWORD BOOKS No Free Left: The Futures of Indian Communism 2015 The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South. 2013 Arab Spring, Libyan Winter. 2012 The Darker Nations: A Biography of the Short-Lived Third World. 2009 Namaste Sharon: Hindutva and Sharonism Under US Hegemony. 2003 War Against the Planet: The Fifth Afghan War, Imperialism and Other Assorted Fundamentalisms. 2002 Enron Blowout: Corporate Capitalism and Theft of the Global Commons, co-authored with Prabir Purkayastha. 2002 Dispatches from the Arab Spring: Understanding the New Middle East, co-edited with Paul Amar. 2013 Dispatches from Pakistan, co-edited with Madiha R. Tahir and Qalandar Bux Memon. 2012 Dispatches from Latin America: Experiments Against Neoliberalism, co-edited with Teo Balvé. 2006 OTHER TITLES BY VIJAY PRASHAD Uncle Swami: South Asians in America Today. 2012 Keeping Up with the Dow Joneses: Stocks, Jails, Welfare. 2003 The American Scheme: Three Essays. 2002 Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. 2002 Fat Cats and Running Dogs: The Enron Stage of Capitalism. 2002 The Karma of Brown Folk. 2000 Untouchable Freedom: A Social History of a Dalit Community. 1999 First published in November 2017 E-book published in December 2017 LeftWord Books 2254/2A Shadi Khampur New Ranjit Nagar New Delhi 110008 INDIA LeftWord Books is the publishing division of Naya Rasta Publishers Pvt. Ltd. leftword.com © Vijay Prashad, 2017 Front cover: Bolshevik Poster in Russian and Arabic Characters for the Peoples of the East: ‘Proletarians of All Countries, Unite!’, reproduced from Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution, New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1921 Sources for images, as well as references for any part of this book are available upon request.