Global Perestroika by Vijay Prashad, Professor of International Studies, Trinity College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Third World to the Global South Written by Alina Sajed

From the Third World to the Global South Written by Alina Sajed This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. From the Third World to the Global South https://www.e-ir.info/2020/07/27/from-the-third-world-to-the-global-south/ ALINA SAJED, JUL 27 2020 The term ‘Global South’ is not an uncontroversial one. There have been many debates in the last few decades regarding its usefulness, both analytical and historical, but especially its connection to another equally debated term, ‘Third World.’ In the midst of these debates, however, there has appeared a loose consensus around their meaning and their linkages. I will attempt to elucidate here the meaning and histories of both terms, and the connections and ruptures between them. To do so, I will be drawing on the work of several Marxist intellectuals, such as L.S. Stavrianos and Vijay Prashad, among others. It must be emphasized, however, that the term Global South cannot be considered separately from that of the Third World. I argue that the idea of Global South could not have emerged without taking seriously the conceptual work done by the term Third World, and indeed without the legacy left by Third Worldism and its historical landmarks. The discussion below devotes significant space to understanding not only the emergence of the term Third World, but especially the central role played by processes of capitalist expansion to conceptualizing both Third World and Global South, albeit in different ways and at different historical junctures. -

Arab Spring, Libyan Winter Vijay Prashad Remarks

Arab Spring, Libyan Winter Vijay Prashad remarks. Arab Spring, Libyan Winter is less about predicting the future and more about showing us how the Atlantic powers insinuated themselves into the Arab Spring, to attempt to create a Libyan Winter to the advantage of their national interests, the interest of the multinational oil firms and the neoliberal reformers within Libya. Part I: Arab Spring. I. Bread When the unwashed began to assert themselves in France, the royalty scoffed at them. What they wanted was bread, whose price skyrocketed in 1774–75. Taking to the streets in remarkable numbers, the people demanded fair prices for bread, their main staple. In reaction to la guerre des farines, the flour war, Marie Antoinette proposed that the poor “eat cake.” After the Revolution removed the monarchy and its élèves from the thrones of power, the new government hastened to subsidize bread. Hunger broke the back of fear. It is the lesson for the ages. It was a lesson for North Africa in late 2010. In the last two quarters of 2010, the IMF Food Price Index rose by thirty percent. Grain prices soared by sixty percent. Protestors in Tunisia came onto the streets in December with baguettes raised in the air. In Egypt, protestors took to the streets in January chanting, “They are eating pigeon and chicken, and we are eating beans all the time.” Hunger and inequality drove the protests. Their governments hastened to up their subsidies, but it was too little, too late. The question of bread reveals a great deal about the delinquent states in Egypt and Tunisia. -

War Rites and Women's Rights

Smith ScholarWorks Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications Study of Women and Gender Spring 2005 Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth Armstrong Smith College, [email protected] Vijay Prashad Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Elisabeth and Prashad, Vijay, "Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights" (2005). Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/swg_facpubs/22 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] Solidarity: War Rites and Women's Rights Author(s): Elisabeth B. Armstrong and Vijay Prashad Source: CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, terror wars (spring 2005), pp. 213- 253 Published by: Michigan State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41949472 Accessed: 14-01-2020 19:07 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Michigan State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to CR: The New Centennial Review This content downloaded from 131.229.19.247 on Tue, 14 Jan 2020 19:07:36 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Solidarity War Rites and Women's Rights Elisabeth b. -

To Be Effective, Socialism Must Adapt to 21St Century Needs

To Be Effective, Socialism Must Adapt To 21st Century Needs Vijay Prashad IS socialism making a comeback? If so, what exactly is socialism, why did it lose steam toward the latter part of the 20th century, and how do we distinguish democratic socialism, currently in an upward trend in the U.S., from social democracy, which has all but collapsed? Vijay Prashad, executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and a leading scholar in socialist studies and the politics of the global South, offers answers to these questions. C.J. Polychroniou: Socialism represented a powerful and viable alternative to capitalism from the mid-1800s all the way up to the third quarter of the 20th century, but entered a period of crisis soon thereafter for reasons that continue to be debated today. In your view, what are some of the main political, economic and ideological factors that help explain socialism’s setback in the contemporary era? Vijay Prashad: The first thing to acknowledge is that “socialism” is not merely a set of ideas or a policy framework or anything like that. Socialism is a political movement, a general way of referring to a situation where the workers gain the upper hand in the class struggle and put in place institutions, policies and social networks that advantage the workers. When the political movement is weak and the workers are on the weaker side of the class struggle, it is impossible to speak confidently of “socialism.” So, we need to study carefully how and why workers — the immense majority of humanity — began to see the reservoirs of their strength get depleted. -

Black Masculinity and Obama's Feminine Side

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2009 Our First Unisex President?: Black Masculinity and Obama's Feminine Side Frank Rudy Cooper University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Gender Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Frank Rudy, "Our First Unisex President?: Black Masculinity and Obama's Feminine Side" (2009). Scholarly Works. 1124. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/1124 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUR FIRST UNISEX PRESIDENT?: BLACK MASCULINITY AND OBAMA'S FEMININE SIDE FRANK RUDY COOPERt ABSTRACT People often talk about the significance of Barack Obama's status as our first black President. During the 2008 Presidential campaign, however, a newspaper columnist declared, "If Bill Clinton was once con- sidered America's first black president, Obama may one day be viewed as our first woman president." That statement epitomized a large media discourse on Obama's femininity. In this essay, I thus ask how Obama will influence people's understandings of the implications of both race and gender. To do so, I explicate and apply insights from the fields of identity performance theory, critical race theory, and masculinities studies. With respect to race, the essay confirms my prior theory of "bipolar black masculinity." That is, the media tends to represent black men as either the completely threatening and race-affirming Bad Black Man or the completely comforting and assimilationist Good Black Man. -

Cataracts of Silence

RACISM Durban, South Africa and PUBLIC 3 - 5 September 2001 POLICY Cataracts of Silence Race on the Edge of Indian Thought Vijay Prashad United Nations Research Institute for Social Development 2 The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multidisciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary problems affecting development. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and environmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of national research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. Current research programmes include: Civil Society and Social Movements; Democracy, Governance and Human Rights; Identities, Conflict and Cohesion; Social Policy and Development; and Technology, Business and Society. A list of the Institute’s free and priced publications can be obtained by contacting the Reference Centre. UNRISD work for the Racism and Public Policy Conference is being carried out with the support of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. UNRISD also thanks the governments of Denmark, Finland, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom for their core funding. UNRISD, Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 9173020 Fax: (41 22) 9170650 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unrisd.org Copyright © UNRISD. This paper has not been edited yet and is not a formal UNRISD publication. -

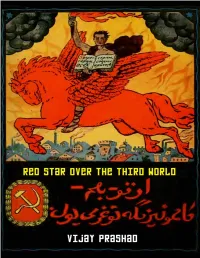

“Red Star Over the Third World” by Vijay Prashad

ALSO BY VIJAY PRASHAD FROM LEFTWORD BOOKS No Free Left: The Futures of Indian Communism 2015 The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South. 2013 Arab Spring, Libyan Winter. 2012 The Darker Nations: A Biography of the Short-Lived Third World. 2009 Namaste Sharon: Hindutva and Sharonism Under US Hegemony. 2003 War Against the Planet: The Fifth Afghan War, Imperialism and Other Assorted Fundamentalisms. 2002 Enron Blowout: Corporate Capitalism and Theft of the Global Commons, co-authored with Prabir Purkayastha. 2002 Dispatches from the Arab Spring: Understanding the New Middle East, co-edited with Paul Amar. 2013 Dispatches from Pakistan, co-edited with Madiha R. Tahir and Qalandar Bux Memon. 2012 Dispatches from Latin America: Experiments Against Neoliberalism, co-edited with Teo Balvé. 2006 OTHER TITLES BY VIJAY PRASHAD Uncle Swami: South Asians in America Today. 2012 Keeping Up with the Dow Joneses: Stocks, Jails, Welfare. 2003 The American Scheme: Three Essays. 2002 Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. 2002 Fat Cats and Running Dogs: The Enron Stage of Capitalism. 2002 The Karma of Brown Folk. 2000 Untouchable Freedom: A Social History of a Dalit Community. 1999 First published in November 2017 E-book published in December 2017 LeftWord Books 2254/2A Shadi Khampur New Ranjit Nagar New Delhi 110008 INDIA LeftWord Books is the publishing division of Naya Rasta Publishers Pvt. Ltd. leftword.com © Vijay Prashad, 2017 Front cover: Bolshevik Poster in Russian and Arabic Characters for the Peoples of the East: ‘Proletarians of All Countries, Unite!’, reproduced from Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution, New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1921 Sources for images, as well as references for any part of this book are available upon request. -

In the Ruins of the Present

IN THE RUINS OF THE PRESENT Tricontinental Working Document, no. 1 March 2018 Every few months, Tricontinental will release a working document. These documents are intended to stimu-late debate about issues of importance. Please use them as you see fit – reproduce them, translate them, and discuss the issues raised by them. We hope that readers find the series useful. We are always open to criticism and guidance, not only about the contents of the working document, but also about the form itself. If you have any comments about the papers, or would like to submit a document for the series, please write to [email protected] or [email protected]. In the Ruins of the Present Vijay Prashad. Ağaca balta vurmuşlar ‘sapı bendendir’ demiş. When the axe came into the forest, the trees said: the handle is one of us. (Turkish proverb). Raoul Peck, the Haitian filmmaker, opens his film – predicament. They know the punishment that Der Junge Karl Marx (2017) – in the forests of Prussia. they face: indignity, starvation and death. This Peasants gather fallen wood. They look cold and they know. What they do not know is their crime. hungry. We hear horses in the distance. The guards and What have they done to deserve this? the aristocrats are near. They have come to claim the right to everything in the forest. The peasants run. But The Dominican-American writer Junot Diaz they have no energy. They fall. The whips and lances visited Haiti after the devastating earthquake of of the aristocrats and the guards strike them. -

Anatomy of the Islamic State

The Marxist, XXX 3, July–September 2014 VIJAY PRASHAD Anatomy of the Islamic State ISLAMIC STATE Execution of Western journalists and aid workers and a threat to the US allies in Iraqi Kurdistan brought the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) onto the concern list of the West, and subsequently to the world. That the IS had already seized the Iraqi cities of Fallujah and Ramadi and the Syrian cities of Raqqa and Deires-Zor almost a year beforehand had not sent up the amber light of caution. Already Iraq and Syria had been seriously threatened by the IS, which had captured land that straddle the two countries and had been in control of the Omar and Tanakoil fields in eastern Syria from where it had begun to accumulate its revenues. In January 2014, two ambassadors from western European countries told me that my reports had greatly exaggerated the influence of ISIS. They wanted to maintain the view that the Syrian civil war was between the forces of Freedom (the rebels) and Authoritarianism (the Syrian government). That Cold War derived framework had not been applicable to Syria at least since early 2012, when dangerous forces had inserted themselves into the emergent chaos in northern Syria. By 2014, those forces had seriously threatened not only Damascus, but the entire region, from the borders of Iran to the borders of Saudi Arabia. As his forces spread themselves across this land, the leader of ISIS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi did something audacious: he anointed himself the Caliph of Islam and dropped the geographical limitation to his organisation. -

Jonathan R. Bailyn

THE UNITED STATES and ISRAEL: CULTURAL FOUNDATIONS of the SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP JONATHAN R. BAILYN Submitted to the Department of Sociology and Anthropology ofAmherst College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors. Faculty Advisor: Jan Dizard 4 16 2007 Israel was not created in order to disappear - Israel will endure and flourish. It is the child of hope and home of the brave. It can neither be broken by adversity nor demoralized by success. It carries the shield of democracy and it honors the sword of freedom. -President John F. Kennedy the UNITED STATES and ISRAEL: CULTURAL FOUNDATIONS of the SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP __ INTRODUCTION: THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP 1 I. FOUNDATIONAL MYTHS 19 II. JEWISH ASSIMILATION 51 III. RELIGIOUS HERITAGE 81 IV. THE HOLOCAUST 103 V. STRATEGIC ALLIES 127 CONCLUSION: THE LIMITS 145 bibliography 163 __ Jonathan R. Bailyn INTRODUCTION: THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP THE LOBBY In March 2006, John J. Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago and Stephen M. Walt of Harvard University published The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy on Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government webpage. It was submitted as a digital “working paper” on March 13, 2006, and on March 23 was run in print by the London Review of Books.1 In the piece Mearsheimer and Walt contend that American foreign policy in the Middle East “is due almost entirely…to the activities of the ‘Israel Lobby.’”2 The Israel Lobby has managed to “skew” and “divert” U.S. foreign policy away from its own national interest while simultane- ously “convincing” America that U.S. -

The Occupation of the American Mind

THE OCCUPATION OF THE AMERICAN MIND ISRAEL’S PUBLIC RELATIONS WAR IN THE UNITED STATES A DOCUMENTARY NARRATED BY ROGER WATERS “It doesn’t matter if justice is on your side. You have to depict your position as just.” —Benjamin Netanyahu, Prime Minister of Israel Over the past few years, Israel’s ongoing military occupation of Palestinian territory and repeated invasions of the Gaza strip have triggered a fierce backlash against Israeli policies virtually everywhere in the world—except the United States. The Occupation of the American Mind takes an eye-opening look at this critical exception, zeroing in on pro-Israel public relations efforts within the U.S. Narrated by Roger Waters and featuring leading observers of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict and U.S. media culture, the film explores how the Israeli government, the U.S. government, and the pro-Israel lobby have joined forces, often with very different motives, to shape American media coverage of the conflict in Israel’s favor. From the U.S.-based public relations campaigns that emerged in the 1980s to today, the film provides a sweeping analysis of Israel’s decades-long battle for the hearts, minds, and tax dollars of the American people in the face of widening international condemnation of its increasingly right-wing policies. ISRAEL’S PUBLIC THE OCCUPATION OF RELATIONS WAR IN THE AMERICAN MIND THE UNITED STATES FILMMAKERS' STATEMENT Over the past 25 years, the Media Education Foundation has produced dozens of educational films that examine how mainstream media narratives shape our understanding of the world. A number of these films have focused explicitly on mainstream news coverage of crucial policy issues. -

Dream History of the Global South

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 4 (1): 43 - 53 (May 2012) Prashad, Dream history of the global South Dream history of the global South1 Vijay Prashad Abstract This article provides a brief history of the Third World project, the project of the Non-Allied Movement, and the project of the South, and serves to give a larger context of the befell the Arab world, and the revolution that started in 2011. It shows on one hand the attempts to decolonize the Third World and freeing it from Western imperialism and domination, and on the other hand the continuing project of imperialism and its effects on the Third World, including the Arab world. It also discusses the changing global political economy and the possibilities of the future global system. Part I: The Third World project2 “The Third World today faces Europe like a colossal mass whose project should be to try to resolve the problem to which Europe has not been able to find the answers.” Franz Fanon, 1961 The massive wave of anti-colonial movements that opened with the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and came into its own by the last quarter of the 19th century, broke the legitimacy of colonial domination. No longer could it be said that a European power had the manifest destiny to govern other peoples. When such colonial adventures were tried out, they were chastised for being immoral. In 1928, the anti-colonial leaders gathered in Brussels for a meeting of the League Against Imperialism. This was the first attempt to create a global platform to unite the visions of the anti-colonial movements from Africa, Asia and Latin America.