Monastic Discourse on the Ottoman Threat in 14Th- and 15Th-Century Serbian Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

Cultural Heritage, Reconstruction and National Identity in Kosovo

1 DOI: 10.14324/111.444.amps.2013v3i1.001 Title: Identity and Conflict: Cultural Heritage, Reconstruction and National Identity in Kosovo Author: Anne-Françoise Morel Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 3, no.1. May 2013 Affiliation: Universiteit Gent Abstract: The year 1989 marked the six hundredth anniversary of the defeat of the Christian Prince of Serbia, Lazard I, at the hands of the Ottoman Empire in the “Valley of the Blackbirds,” Kosovo. On June 28, 1989, the very day of the battle's anniversary, thousands of Serbs gathered on the presumed historic battle field bearing nationalistic symbols and honoring the Serbian martyrs buried in Orthodox churches across the territory. They were there to hear a speech delivered by Slobodan Milosevic in which the then- president of the Socialist Republic of Serbia revived Lazard’s mythic battle and martyrdom. It was a symbolic act aimed at establishing a version of history that saw Kosovo as part of the Serbian nation. It marked the commencement of a violent process of subjugation that culminated in genocide. Fully integrated into the complex web of tragic violence that was to ensue was the targeting and destruction of the region’s architectural and cultural heritage. As with the peoples of the region, this heritage crossed geopolitical “boundaries.” Through the fluctuations of history, Kosovo's heritage had already become subject to divergent temporal, geographical, physical and even symbolical forces. During the war it was to become a focal point of clashes between these forces and, as Anthony D. Smith argues with regard to cultural heritage more generally, it would be seen as “a legacy belonging to the past of ‘the other,’” which, in times of conflict, opponents try “to damage or even deny.” Today, the scars of this conflict, its damage and its denial are still evident. -

Looking Into Iraq

Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch cc79-cover.qxp 28/07/2005 15:27 Page 2 Chaillot Paper Chaillot n° 79 In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) beca- Looking into Iraq me an autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of the European security and defence policy. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between European experts and decision-makers at all levels. Chaillot Papers are monographs on topical questions written either by a member of the ISS research team or by outside authors chosen and commissioned by the Institute. Early drafts are normally discussed at a semi- nar or study group of experts convened by the Institute and publication indicates that the paper is considered Edited by Walter Posch Edited by Walter by the ISS as a useful and authoritative contribution to the debate on CFSP/ESDP. Responsibility for the views expressed in them lies exclusively with authors. Chaillot Papers are also accessible via the Institute’s Website: www.iss-eu.org cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 1 Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch Institute for Security Studies European Union Paris cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 2 Institute for Security Studies European Union 43 avenue du Président Wilson 75775 Paris cedex 16 tel.: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 30 fax: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss-eu.org Director: Nicole Gnesotto © EU Institute for Security Studies 2005. -

TODAY We Are Celebrating Our Children's Slava SVETI SAVA

ST. ELIJAH SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH 2200 Irwin Street, Aliquippa, PA 15001 Rev. Branislav Golic, Parish Priest e-mail: [email protected] Parish Office: 724-375-4074 webpage: stelijahaliquippa.com Center Office: 724-375-9894 JANUARY 26, 2020 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Saint Sava Born Prince Rastko Nemanjic, son of the Serbian ruler and founder of the Serbian medieval state Stefan Nemanja, St. Sava became the first Patriarch of Serbia (1219-1233) and is an important Saint in the Serbian Orthodox Church. As a young boy, Rastko left home to join the Orthodox monastic colony on Mount Athos and was given the name Sava. In 1197 his father, King Stefan Nemanja, joined him. In 1198 they moved to and restored the abandoned monastery Hilandar, which was at that time the center of Serbian Orthodox monastic life. St. Sava's father took the monastic vows under the name Simeon, and died in Hilandar on February 13, 1200. He is also canonized a saint of the Church. After his father's death, Sava retreated to an ascetic monastery in Kareya which he built himself in 1199. He also wrote the Kareya typicon both for Hilandar and for the monastery of ascetism. The last typicon is inscribed into the marble board at the ascetic monastery, which today also exists there. He stayed on Athos until the end of 1207, when he persuaded the Patriarch of Constantinople to elevate him to the position of first Serbian archbishop, thereby establishing the independence of the archbishopric of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the year 1219. Saint Sava is celebrated as the founder of the independent Serbian Orthodox Church and as the patron saint of education and medicine among Serbs. -

The Symbolic Significance of the String-Course in Orthodox Sacred Architecture

European Journal of Science and Theology, June 2007, Vol.3, No.2, 61-70 _______________________________________________________________________ THE SYMBOLIC SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STRING-COURSE IN ORTHODOX SACRED ARCHITECTURE Mihaela Palade* University Bucharest, Faculty of Orthodox Theology, Department of Sacred Art, Str. Sf. Ecaterina nr. 2,040155 Bucharest IV, Romania (Received 7 May 2007) Abstract A brief analysis of the decorative system peculiar to Romanian sacred architecture leads to singling out an element that distinctly stands out, being present in the overwhelming majority of the respective worship places. It is the string-course, a protruding ornament that circumscribes the median part of the façade and is made of various materials: stone, brick, plaster. At first sight it appears to be an agreeable, ingenious aesthetic solution, since the horizontal line it emphasizes enters into a pleasant dialogue with the vertical arches, windows, pillars and other upright elements. The present essay points out that this element is not a mere aesthetic device, but has a deep symbolic significance related to that of the church it girdles. Keywords: girding one’s waist with the belt, the Church – Christ’s mystical body, string- course, girding one with strength Motto: Thou hast turned for me my mourning into dancing; Thou hast loosed my sackcloth, And girded me with gladness. (Psalm 29/30.10, 11) 1. The presence of the string-course in the Orthodox sacred architecture; types and variations exemplified within the Romanian area In the Byzantine architecture, one or several horizontal profiles mark the outside decoration, surrounding the façade either from end to end or only partially. -

Hotel Prohor Pcinjski, Spa Bujanovac Media Center Bujanovac SPA Phone: +38164 5558581; +38161 6154768; [email protected]

Telenet Hotels Network | Serbia Hotel Prohor Pcinjski, Spa Bujanovac Media Center Bujanovac SPA Phone: +38164 5558581; +38161 6154768; www.booking-hotels.biz [email protected] Hotel Prohor Pcinjski, Spa Bujanovac Hotel has 100 beds, 40 rooms in 2 single rooms, 22 double rooms, 5 rooms with three beds, and 11 apartments. Hotel has restaurant, aperitif bar, and parking. Restaurant has 160 seats. All rooms have telephone, TV, and SATV. Bujanovac SPA Serbia Bujanovacka spa is located at the southernmost part of Serbia, 2,5 km away from Bijanovac and 360 km away from Belgrade, at 400 m above sea level. Natural curative factors are thermal mineral waters, curative mud [peloid] and carbon dioxide. Medical page 1 / 9 Indications: rheumatic diseases, recuperation states after injuries and surgery, some cardiovascular diseases, peripheral blood vessel diseases. Medical treatment is provided in the Institute for specialized rehabilitation "Vrelo" in Bujanovacka Spa. The "Vrelo" institute has a diagnostic-therapeutic ward and a hospital ward within its premises. The diagnostic-therapeutic ward is equipped with the most modern means for diagnostics and treatment. Exceptional treatment results are achieved by combining the most modern medical methods with the curative effect of the natural factors - thermal mineral waters, curative mud and natural gas. In the vicinity of Bujanovacka Spa there is Prohorovo, an area with exceptional natural characteristics. In its centre there is the St. Prohor Pcinjski monastery, dating from the 11th century, with a housing complex that was restored for the purpose of tourist accommodation. The Prohorovo area encompasses the valley of the river Pcinja and Mounts Kozjak and Rujan, and is an area exceptionally pleasant for excursions and hunting. -

The Enchanting Pannonian Beauty – Fruška Gora Tour Guide

Tourism Organisation of FREE COPY Vojvodina FRUŠKA GORA TOUR GUIDE The Enchanting Pannonian Beauty www.vojvodinaonline.com SERBIA Čelarevo NOVI SAD PETROVARADIN BAČKA PALANKA Veternik Futog Šarengrad DUNAV Begeč Ilok Neštin Susek Sremska Kamenica DANUBE Čerević Ledinci Banoštor Rakovac SREMSKI Beočin KARLOVCI Šakotinac Bukovac Man. Rakovac Popovica St.Rakovac Orlovac Testera St.Ledinci Lug Man. Paragovo FT Sviloš Grabovo Andrevlje Beočin PM Vizić Srednje brdo Stražilovo Brankov grob Man. Divša FT Osovlje Zmajevac PM Sot Ljuba Brankovac Šidina Akumulacija Dom PTT Bikić Do Sot PM Debeli cer Crveni čot V.Remeta Berkasovo Lovište Vorovo Moharac PM Iriški venac Man. Velika Lipovača Privina Akumulacija Ravne Remeta Papratski do Glava Moharač Stara Bingula Venac Letenka Man. Man. Grgeteg Privina glava Jezero Grgeteg Bruje Man. Petkovica Man. Stari Man. VRDNIK Man. Jazak Ravanica Kuveždin Man. Šišatovac Šišatovac Ležimir Man. Krušedol Man. Jazak Man. Neradin Krušedol Erdevik Bešenovo Man. Mala Divoš Remeta Gibarac Jazak Akumulacija M.Remeta Šelovrenac Akumulacija Remeta Akumulacija Grgurevci IRIG Bingula Manđelos Šuljam ČORTANOVAČKA ŠUMA Bačinci Bešenovo Manđelos DUNAV Čalma Akumulacija Akumulacija Kukujevci Vranjaš Kudoš Akumulacija Stejanovci Čortanovci 2 Stejanovci An Island in the Sea of Panonian Grain ruška gora is an island-mountain, an island in the sea of Panonian grain. It is sit- uated in Vojvodina, in the north of Serbia. It is immersed in the large plain of the FPanonian basin. Once it was splashed by the waves of the Panonian Sea, where- as today, towards its peaks climb regional and local roads that reveal beautiful local sto- ries about nature, ecology, the National Park, monasteries, tame mountain villages and temperamental people. -

The Ottoman State and Semi-Nomadic Groups Along

HStud 27 (2013)2, 219–235 DOI: 10.1556/HStud.27.2013.2.2 THE OTTOMAN STATE AND SEMI-NOMADIC GROUPS ALONG THE OTTOMAN DANUBIAN SERHAD (FRONTIER ZONE) IN THE LATE 15TH AND THE FIRST HALF OF THE 16TH CENTURIES: CHALLENGES AND POLICIES NIKOLAY ANTOV University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA E-mail: [email protected] The main subject of this article is the relationship between the Ottoman state and semi-nomadic groups in the Ottoman Danubian frontier zone (serhad) in the late 15th and the first half of the 16th century. Taking the two extremities of the Danubian frontier zone – the provinces of Smederevo in Serbia and Silistre in the northeastern Balkans – as case studies, the article compares the ways in which the Ottoman state dealt with semi-nomadic Vlachs at one end of the frontier zone and Turcoman yürüks (and related groups) at the other. Placing the subject in the broader context of the historical development of the Danubian frontier zone, the author analyzes the Ottoman state’s changing policies toward these two groups. Taking into account the largely different historical legacies and demographic make-ups, the article analyzes the many commonalities (as well as some important differences) in the way the Ot- toman government integrated such groups in its administrative structure. It high- lights the process in which such semi-nomadic groups, traditionally utilized by the Ottoman state as auxiliary soldiers, were gradually “tamed” by the state in the course of the 16th century, becoming gradually sedentarized and losing their privi- leged status. Keywords: Ottoman, frontier, 16th century, semi-nomads, Vlachs, Yürüks The frontier and (pastoral) nomadism are two concepts that have fascinated (Mid- dle Eastern and) Ottomanist historians from the very conception of these fields of historical inquiry. -

SEIA NEWSLETTER on the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism

SEIA NEWSLETTER On the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism _______________________________________________________________________________________ Number 182: November 30, 2010 Washington, DC The Feast of Saint Andrew at sues a strong summons to all those who by HIS IS THE ADDRESS GIVEN BY ECU - The Ecumenical Patriarchate God’s grace and through the gift of Baptism MENICAL PATRIARCH BARTHOLO - have accepted that message of salvation to TMEW AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE renew their fidelity to the Apostolic teach- LITURGY COMMEMORATING SAINT S IS TRADITIONAL FOR THE EAST F ing and to become tireless heralds of faith ANDREW ON NOVEMBER 30: OF ST. ANDREW , A HOLY SEE in Christ through their words and the wit- Your Eminence, Cardinal Kurt Koch, ADELEGATION , LED BY CARDINAL ness of their lives. with your honorable entourage, KURT KOCH , PRESIDENT OF THE PONTIFI - In modern times, this summons is as representing His Holiness the Bishop of CAL COUNCIL FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN urgent as ever and it applies to all Chris- senior Rome and our beloved brother in the UNITY , HAS TRAVELLED TO ISTANBUL TO tians. In a world marked by growing inter- Lord, Pope Benedict, and the Church that PARTICIPATE IN THE CELEBRATIONS for the dependence and solidarity, we are called to he leads, saint, patron of the Ecumenical Patriarchate proclaim with renewed conviction the truth It is with great joy that we greet your of Constantinople. Every year the Patriar- of the Gospel and to present the Risen Lord presence at the Thronal Feast of our Most chate sends a delegation to Rome for the as the answer to the deepest questions and Holy Church of Constantinople and express Feast of Sts. -

KOKINO WEB 02 04 2018-Min.Pdf

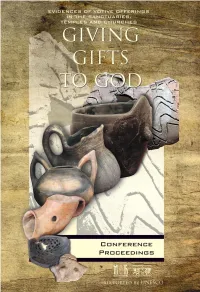

NATIONAL INSTITUTION MUSEUM OF KUMANOVO 1 Published by National Institution Museum of Kumanovo, In a partnership with Ministry of Culture and Archaeological Museum of Macedonia Edited by Dejan Gjorgjievski Editorial board: Bogdan Tanevski (Museum of Kumanovo, Kumanovo), Jovica Stankovski (Museum of Kumanovo, Kumanovo), Aleksandra Papazova (Archaeological Museum of Macedonia, Skopje), Aleksandar Bulatović (Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade), Bojana Plemić (College of Tourism, Belgrade), Carolyn Snively (Gettysburg College, Pennsylvania), Philip Mihaylov (Museum of Pernik, Pernik), Anastasios Antonaras (Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki) All rights reserved. All parts of this publication are protected by copyright. Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution. This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems. This publication has been peer reviewed. CIP - Каталогизација во публикација Национална и универзитетска библиотека “Св. Климент Охридски”, Скопје 902:2-522(497)(062) 902:338.483.12(497)(062) 902.2(497)(062) INTERNATIONAL archaeological conference “Kokino” (1 & 2 ; 2016-2017 ; Skopje, Kumanovo) Giving gift to God : evidences of votive offerings in the sanctuaries, temples and churches : proceedings of the 1 st & 2nd International archaeological conference “Kokino”, held in Skopje & Kumanovo, 2016-2017 / [edited by Dejan Gjorgjievski]. - Kumanovo -

New Europe College Black Sea Link Program Yearbook 2014-2015 Program Yearbook 2014-2015 Black Sea Link

New Europe College Black Sea Link Program Yearbook 2014-2015 Program Yearbook 2014-2015 Black Sea Link ANNA ADASHINSKAYA ASIYA BULATOVA NEW EUROPE COLLEGE DIVNA MANOLOVA OCTAVIAN RUSU LUSINE SARGSYAN ANTON SHEKHOVTSOV NELLI SMBATYAN VITALIE SPRÎNCEANĂ ISSN 1584-0298 ANASTASIIA ZHERDIEVA CRIS Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai Copyright – New Europe College ISSN 1584-0298 New Europe College Str. Plantelor 21 023971 Bucharest Romania www.nec.ro; e-mail: [email protected] Tel. (+4) 021.307.99.10, Fax (+4) 021. 327.07.74 DIVNA MANOLOVA Born in 1984, in Bulgaria Ph.D. in Medieval Studies and in History, Central European University, 2014 Dissertation: Discourses of Science and Philosophy in the Letters of Nikephoros Gregoras Fellowships and grants: Visiting Research Fellow, Brown University, Department of Classics (2013) Doctoral Research Support Grant, Central European University (2013) Medieval Academy of America Etienne Gilson Dissertation Grant (2012) Junior Fellow, Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Koç University (2012–2013) Junior Fellow in Byzantine Studies, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection (2011–2012) Participation in international conferences in Austria, Bulgaria, France, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and United States of America. Publications and translations in the fields of Byzantine Studies, History of Medieval Philosophy, and History of Medieval Science. WHO WRITES THE HISTORY OF THE ROMANS? AGENCY AND CAUSALITY IN NIKEPHOROS GREGORAS’ HISTORIA RHŌMAÏKĒ Abstract The present article inquires -

The Memorial Church of St. Sava on Vračar Hill in Belgrade

Balkanologie Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires Vol. VII, n° 2 | 2003 Volume VII Numéro 2 Nationalism in Construction: The Memorial Church of St. Sava on Vračar Hill in Belgrade Bojan Aleksov Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/494 DOI: 10.4000/balkanologie.494 ISSN: 1965-0582 Publisher Association française d'études sur les Balkans (Afebalk) Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2003 Number of pages: 47-72 ISSN: 1279-7952 Electronic reference Bojan Aleksov, « Nationalism in Construction: The Memorial Church of St. Sava on Vračar Hill in Belgrade », Balkanologie [Online], Vol. VII, n° 2 | 2003, Online since 19 February 2009, connection on 17 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/494 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/balkanologie.494 © Tous droits réservés Balkanologie VII (2), décembre 2003, p. 47-72 \ 47 NATIONALISM IN CONSTRUCTION : THE MEMORIAL CHURCH OF ST. SAVA ON VRAČAR HILL IN BELGRADE Bojan Aleksov* During the combat we all saw St. Sava, robed in white, and seated in a white chariot drawn by white horses, leading us on to victory.1 The role of St. Sava, whom the late Serbian Patriarch German praised as the "Sun of Serbian heaven" in Serbian oral tradition during medieval and Ottoman period was to always watch over Serbian people2. In many popular le gends and folk tales he is the creator of miraculous springs, a master of the for ces of nature with all features of a God who blesses and punishes. Often cruel in punishing and horrendous in his rage, St. Sava, has the features of a primi tive pagan god and, though a Christian saint, in the eyes of popular culture he embodied a pre-Christian pagan divinity or the ancient Serbian god of the un- derworkR In the age of nationalism however, the Serbian cult of St.