Is Nocturnal Foraging in a Tropical Bee an Escape from Interference Competition?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solanaceae) Flower–Visitor Network in an Atlantic Forest Fragment in Southern Brazil

diversity Article Bee Diversity and Solanum didymum (Solanaceae) Flower–Visitor Network in an Atlantic Forest Fragment in Southern Brazil Francieli Lando 1 ID , Priscila R. Lustosa 1, Cyntia F. P. da Luz 2 ID and Maria Luisa T. Buschini 1,* 1 Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Evolutiva da Universidade Estadual do Centro-Oeste, Rua Simeão Camargo Varela de Sá 03, Vila Carli, Guarapuava 85040-080, Brazil; [email protected] (F.L.); [email protected] (P.R.L.) 2 Research Centre of Vascular Plants, Palinology Research Centre, Botanical Institute of Sao Paulo Government, Av. Miguel Stéfano, 3687 Água Funda, São Paulo 04045-972, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 November 2017; Accepted: 8 January 2018; Published: 11 January 2018 Abstract: Brazil’s Atlantic Forest biome is currently undergoing forest loss due to repeated episodes of devastation. In this biome, bees perform the most frequent pollination system. Over the last decade, network analysis has been extensively applied to the study of plant–pollinator interactions, as it provides a consistent view of the structure of plant–pollinator interactions. The aim of this study was to use palynological studies to obtain an understanding of the relationship between floral visitor bees and the pioneer plant S. didymum in a fragment of the Atlantic Forest, and also learn about the other plants that interact to form this network. Five hundred bees were collected from 32 species distributed into five families: Andrenidae, Apidae, Colletidae, Megachilidae, and Halictidae. The interaction network consisted of 21 bee species and 35 pollen types. -

Jupiter and the Bee

Jupiter and the Bee At the beginning of time, the honeybee had no stinger. This left the bee with no way to protect her honey. The bee worked very hard to make her honey. But people were always taking it from her. This made the bee mad. The bee needed help. She needed a way to protect her honey. The bee decided to ask the gods for help. She took some of her best honey. Then she flew to Mount Olympus. That is where the gods lived. The bee went to see Jupiter. Jupiter was king of the gods. She brought him the honey as a gift. © 2018 Reading Is Fundamental • Content and art created by Simone Ribke Jupiter and the Bee Jupiter loved the honey. He had never tasted something so sweet. Jupiter said it was a great gift. In return, Jupiter promised to give the bee a gift. He asked her what she wanted. The bee asked Jupiter to give her a stinger. She would use it to keep people away from her honey. She would sting people who tried to take honey from her. Jupiter did not like this idea because he loved people. He did not want them to get stung. But he had made her a promise. Jupiter gave the bee a stinger, but using it came at a price. If she uses her stinger, she will die. The bee would have to choose. Will she protect her honey and die? Or will she let people take her honey and live? Jupiter gave stingers to all bees. -

What the Riddle-Makers Have Hidden Behind the Fire of a Dragon

Volume 38 Number 2 Article 7 5-15-2020 What the Riddle-Makers Have Hidden Behind the Fire of a Dragon Laurence Smith Independent Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Laurence (2020) "What the Riddle-Makers Have Hidden Behind the Fire of a Dragon," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 38 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol38/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Classical mythology, folklore, and fairy tales are full of dragons which exhibit fantastic attributes such as breathing fire, hoarding treasure, or possessing more than one head. This study maintains that some of these puzzling phenomena may derive from riddles, and will focus particularly on some plausible answers that refer to a real creature that has for millennia been valued and hunted by man: the honeybee. -

The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art

Dominican Scholar Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Theses Student Scholarship May 2019 The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art Maura Wilson Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Wilson, Maura, "The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art" (2019). Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses. 6. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor and approved by the department chair, has been presented to and accepted by the Master of Arts in Humanities Program in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities. An electronic copy of of the original signature page is kept on file with the Archbishop Alemany Library. Maura Wilson Candidate Joan Baranow, PhD Program Chair Joan Baranow, PhD First Reader Sandra Chin, MA Second Reader This master's thesis is available at Dominican Scholar: https://scholar.dominican.edu/humanities- masters-theses/6 i The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art By Maura Wilson This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor and approved by the program chair, has been presented to an accepted by the Department of Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA May 2019 ii iii Copyright © Maura Wilson 2019. -

Identifying Bee and Wasp Nests

IDENTIFYING BEE AND WASP NESTS Bumblebees, honey bees, hornets and yellow jackets may look alike from a distance, but their impact on your health, your yard and the ecosystem varies by species. Knowing how to recognize each species’ nest can help identify which of these buzzing insects are making themselves at home in your backyard – and allow for safe removal of any nests on your property. Bumblebees Bumblebees are not overly aggressive and rarely sting STRUCTURE: More disorganized than unless disturbed or threatened. These resourceful bees honey bee nests build nests that typically contain far fewer members than honey bees. MATERIALS USED: Dry grass or plant material surrounded by wax cells LOCATION: Dry, protected and hidden cavities below ground, on or near ground level, such as: Rodent tunnels Structural voids Piles of leaves Abandoned bird nests Honey Bees Although one of the most popular bees, honey bees only STRUCTURE: Impressively large nests represent a small percent of bee species and build nests made of six-sided tubes that to produce and store honey. create honey combs MATERIALS USED: Wax bonded to honey comb cells LOCATION: Areas that scout bees believe are appropriate for their colony, such as: Inside tree cavities Under edges of objects On rock crevices Carpenter Bees STRUCTURE: These excavators feed on plant pollen and nectar and Excavated galleries made up of tunnels with a round, drill are known for their ability to construct nests in wooden hole-size entrance structures. MATERIALS USED: Wood pulp, sticks, twigs LOCATION: Dry, unpainted and weathered wooden objects, particularly: Railings Roof eaves Window sills Doors Decks Fences Hornets When hornets perceive threats near their hives, they become STRUCTURE: Ball-shaped and made of aggressive and can deliver painful stings. -

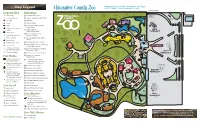

Map Legend 10001 W

Map Legend 10001 W. Bluemound Rd., Milwaukee, WI 53226 414-771-3040 www.milwaukeezoo.org Milwaukee County Zoo Bluemound Rd. Legend Key Buildings Auto teller 8 Animal Health Center Walk-In Entrance Zoofari Change Machine 9 Aquatic & Reptile Center (ARC) Drive-in Exit Animal Health Entrance Conference Center Center First Aid 0 Australia Sea Lion Birds Food - Dairy Complex Show g s Gifts = Dohmen Family Foundation Special Hippo Home Exhibit Handicap/Changing Macaque Island Zebra Station q Family Farm & Public Affairs Office Flamingo Parking Lot Information Swan w Florence Mila Borchert Lost Children’s Area Big Cat Country Fish, an Frogs & angut Mold-a-Rama e Herb & Nada Mahler Family Expedition Snakes Or Primates Apes Aviary Welcome Penny Press Dinosaur Center Summer Gorilla r Holz Family Impala Country 2015 Penguins j Private Picnic Areas ARC Bonobo t Idabel Wilmot Borchert Flamingo Theatre Rest Rooms Siamang Exhibit and Overlook Small Mammals Ropes Courses h Strollers sponsored & y Karen Peck Katz Conservation Zip Line by Wilderness Resort Education Center Giraffe Tornado Shelter u Kohl’s Cares for Kids Play Area Parking Lot i Northwestern Mutual Zoo Rides Family Farm Carousel sponsored African e Briggs o A. Otto Borchert Family Waterhol & Stratton by Penzeys Spices Special Exhibits Building a Zoo ebr Terrace Z Safari Train sponsored B. Jungle Birthday Room Lion by North Shore Bank Cheet Family p Peck Welcome Center Big African Kohl’s Farm Cats Savanna Wild ah Theater Sky Safari sponsored Sky JaguarT [ Primates of the World iger Safari South Live alks by PNC* Prairie America Grizzly Bear Snow Animal T Dairy Elephant ] Small Mammals Building Caribou Dogs Leopard Bongo Barn SkyTrail® Explorer Black Parking Lot Elk Bear Red Hippo Butterfly \ Stackner Animal Encounter Panda Garden Butterfly Ropes Courses & Zip Garden Camel W Line sponsored by a Stearns Family Apes of Africa arthog Bee Pachyderm Hive Exhibit Tri City National Bank* Tapir Pachyderm s Taylor Family Humboldt Penguins d Zoomobile sponsored Education d U.S. -

Heraldry & the Parts of a Coat of Arms

Heraldry reference materials The tomb of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou (died 1151) is the first recorded example of hereditary armory in Europe. The same shield shown here is found on the tomb effigy of his grandson, William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury. Heraldry & the Parts of a Coat of Arms From fleur-de-lis.com Here are some charts from Irish surnames.com, but you can look up more specific information for you by searching “charges” and the words that allude to your ancestors’ backgrounds and cultures, if you prefer. Also try: http://www.rarebooks.nd.edu/digital/heraldry/charges/crowns.html for a good reference source on charges. THE COLORS ON COATS OF ARMS Color Meaning Image Generosity Or (Gold) Argent (Silver or White) Sincerity, Peace Justice, Sovereignty, Purpure (Purple) Regal Warrior, Martyr, Military Gules (Red) Strength Azure (Blue) Strength, Loyalty Vert (Green) Hope, loyalty in love Sable (Black) Constancy, Grief Tenne or Tawny (Orange) Worthwhile Ambition Sanguine or Murray Victorious, Patient in Battle (Maroon) LINES ON COATS OF ARMS Name Meaning Image Irish Example Clouds or Air Nebuly Line Wavy Line Sea or Water Gillespie Embattled Fire, Town-Wall Patterson Line Engrailed Earth, Land Feeney Line Invecked Earth, Land Rowe Line Indented Fire Power Line HERALDIC BEASTS Name Meaning Image Irish Example Fierce Courage. In Ireland the Lion represented the 'lion' season, Lawlor Lion prior to the full arrival of Dillon Summer. The symbol can Condon also represent a great Warrior or Chief. Tiger Fierceness and valour Of Regal origin, one of high nature. In Ireland the Fish is associated with the legend of Fionn who became the first to Roche Fish taste the 'salmon of knowledge'. -

Each of the 30 Printable Bingo Cards Below Contains the English

Each of the 30 printable bingo cards below contains the English translation for 24 words randomly drawn from the set of words in the award-winning Linguacious™ Animals vocabulary flashcard game, available in many different foreign languages. Suggestions for how to use this bingo game to help kids acquire vocabulary in the foreign language of your choice can be found on our website: www.linguacious.net crab whale fox walrus rabbit snake frog cat monkey bee rhinoceros sheep owl starfish polar bear hen giraffe bird cow snail buffalo duck tiger eagle To access the foreign language version of each of these words and hear their pronunciation by a native speaker of that language, visit www.linguacious.net or use the award-winning Linguacious™ vocabulary flashcards or posters, also available on our website. deer dog camel whale frog rhinoceros sheep walrus starfish turtle polar bear mouse ostrich dolphin zebra eagle bee bear fish snake penguin buffalo owl grasshopper To access the foreign language version of each of these words and hear their pronunciation by a native speaker of that language, visit www.linguacious.net or use the award-winning Linguacious™ vocabulary flashcards or posters, also available on our website. ladybug fox starfish monkey lion squirrel dog turtle crab camel snake dolphin duck ostrich penguin fish polar bear spider horse tiger elephant grasshopper goat owl To access the foreign language version of each of these words and hear their pronunciation by a native speaker of that language, visit www.linguacious.net or use the award-winning Linguacious™ vocabulary flashcards or posters, also available on our website. -

Bees and Bears – 4.10

MAAREC Publication 4.10 In the mountainous and heavily wooded September 2014 areas of the Mid-Atlantic region, bears are a serious threat to beekeeping operations. Bears can do a great deal of damage to hives and equipment in a short period of time. Bee damage is most common in early spring and summer (April to June) when young adults come out of hibernation, but can also occur during October and November, when the colonies are slowing down reproduction, preparing for winter and have adequate stored honey. It is this time in the fall before bears enter hibernation dens that they are looking for a sweet and protein rich meal. They normally visit apiaries at night, smashing hives to get to the brood and honey and scattering frames and equipment around the apiary. Once bears locate an apiary, they return again and again. Destruction of beehives by bears is not new, but in recent years the problem has escalated. Black bears once ranged over the entire Mid-Atlantic region. Increased urbanization, cultivated acreage, and the trend toward monocultural agriculture have rapidly reduced both bee pasture and suitable bear habitat. Today, bears are mostly limited to wilderness areas but increasingly are appearing in subdivisions and outlying areas. The extensive use of herbicides and insecticides has reduced bee pasture and forced beekeepers to move their outyards into remote areas to avoid pesticide kills. Therefore, some of the safest/best bee forage is located in areas of high bear density. Most of the states in the Mid-Atlantic region have areas that have high bear populations per square mile, and bear population estimates based on bear kill records show an increase for all states in the Mid-Atlantic region. -

(Native) Bee Basics

A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Cover Art: Upper panel: The southeastern blueberry bee Habropoda( laboriosa) visiting blossoms of Rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium virgatum). Lower panel: Female andrenid bees (Andrena cornelli) foraging for nectar on Azalea (Rhododendron canescens). A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics: An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Illustrations by Steve Buchanan A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication United States Department of Agriculture Acknowledgments Edited by Larry Stritch, Ph.D. Julie Nelson Teresa Prendusi Laurie Davies Adams Worker honey bees (Apis mellifera) visiting almond blossoms (Prunus dulcis). Introduction Native bees are a hidden treasure. From alpine meadows in the national forests of the Rocky Mountains to the Sonoran Desert in the Coronado National Forest in Arizona and from the boreal forests of the Tongass National Forest in Alaska to the Ocala National Forest in Florida, bees can be found anywhere in North America, where flowers bloom. From forests to farms, from cities to wildlands, there are 4,000 native bee species in the United States, from the tiny Perdita minima to large carpenter bees. Most people do not realize that there were no honey bees in America before European settlers brought hives from Europe. These resourceful animals promptly managed to escape from domestication. As they had done for millennia in Europe and Asia, honey bees formed swarms and set up nests in hollow trees. -

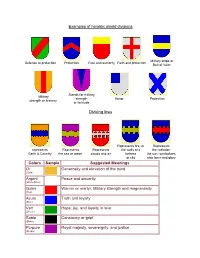

Examples of Heraldic Shield Divisions Dividing Lines Colors Sample

Examples of heraldic shield divisions Military strips or Defense or protection Protection Rule and authority Faith and protection Belt of Valor Stands for military Military strength Honor Protection strength or bravery. or fortitude. Dividing lines Represents fire, or Represents represents Represents Represents the walls of a the radiation Earth & Country the sea or water clouds and air fortress the sun. symbolizes or city also fame and glory Colors Sample Suggested Meanings Or Generosity and elevation of the mind (Gold) Argent Peace and sincerity (White/Silver) Gules Warrior or martyr; Military strength and magnanimity (Red) Azure Truth and loyalty (Blue) Vert Hope, joy, and loyalty in love (Green) Sable Constancy or grief (Black) Purpure Royal majesty, sovereignty, and justice (Purple) Tenne Worthy ambition (Orange) Sanguine Patient in battle, and yet victorious (Maroon) v Charges: Suggested Meanings: Acacia Branch Eternal and affectionate remembrance both for the living and the dead. Acorn Life, immortality and perseverence Anchor Christian emblem of hope and refuge; awarded to sea warriors for special feats performed Also signifies steadfastness and stability. In seafaring nations, the anchor is a symbol of good luck, of safety, and of security Annulet Emblem of fidelity; Also a mark of Cadency of the fifth son Antelope Represents action, agility and sacrifice and a very worthy guardian that is not easily provoked, but can be fierce when challenged Antlers Strength and fortitude Anvil Honour and strength; chief emblem of the smith's trade Arrow Readiness; if with a cross it denotes affliction; a bow and arrow signifies a man resolved to abide the uttermost hazard of battle. -

AMDRO 100530435 Quick Kill Carpenter Bee, Ant & Termite Foam

20 oz. DSC PS 8.75”W x 6.875”H .125” COPY FREE AREA 87093-7-90098_AMDRO Quick Kill Indoor Outdoor Carpenter Bee, Ant & Termite Killer Foam_20180108_25_90098_.pdf E IINSECTS KILLS: Termites* (including subterranean, drywood, dampwood and arboreal), PEEL KIILLS THE HERE AT YOU SEE & Wood Destroying Insects (Powder Post Beetles, Old House Borer, Wharf Borer), THAT ON’T Ants (Including: Argentine, Ghost, White-Footed, foraging Carpenter; Excluding: ONES YOU DON’T THE O Fire, Harvester, Leaf cutter and Pharaoh), Carpenter Bees. FOR USE IN AND AROUND STRUCTURES AND LIMITED OUTDOOR SPOT TREATMENTS: Apartments, Homes, Hobby Greenhouses, Interiorscapes. * Not a substitute for mechanical alteration, soil or foundation treatment. Kills Carpenter Bees, Carpenter Ants, Termites* (including subterranean, drywood, dampwood and arboreal) and other listed wood-damaging insects Where to Use For use in and around structures and limited outdoor spot treatments where wood- damaging insects are seen or suspected How to Use Insert applicator straw into nozzle and spray to apply where insects to be treated are seen or suspected INDOOR/OUTDOOR FIRST AID If swallowed: • Call a poison control center or doctor immediately for treatment advice. Carpenter Bee, • Have a person sip a glass of water if able to swallow. .125” COPY FREE AREA • Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Ant & Termite • Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. KILLER FOAM If inhaled: • Move person to fresh air. • If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambulance, then give artificial respiration, preferably by mouth-to-mouth, if possible.