Bardon Vectis an Outline of the History of Quarrying and Brick Making on the Isle of Wight Until 1939 Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Branch Line Weekend 15-17 March 2019 Photo Report

Branch Line Weekend 15-17 March 2019 Photo report First train of the gala – hauled by the two visiting locomotives (Steve Lee) We present some of the best photos submitted from the weekend, together with the text of the Railway’s Press Release, which acts as a nice summary of the weekend’s activities, rated by many participants as our best ever such event! Event roundup: The Bluebell Railway’s 2019 season of special events kicked off with a 3-day Branch Line event on 15th – 17th March. The event came earlier in the calendar this year, but despite ‘mixed’ weather was very well supported. The Friday proved the most popular day and indeed provided the unique opportunity to see the cavalcade of no less than 4 ex- L.S.W.R. locomotives in the form of Bluebell residents – Adams Radial 30583 and B4 30096 ‘Normandy’ together with visiting W24 ‘Calbourne’ and Beattie Well Tank 30587. Many thanks go to the Isle of Wight Railway for the loan of ‘Calbourne’ and the National Railway Museum for the loan of the Beattie Well Tank for this event. The other locomotives in steam were resident S.E.C.R. trio of ‘H’ 0-4-4T No. 263, ‘P’ 0-6-0T No.178 and ‘01’ 0-6-0 No. 65, plus S.R. ‘Q’ 0-6-0 No. 30541. The Adams Radial which earlier in the year underwent a repaint from LSWR green for the first time since 1983 to British Railways lined black – looked resplendent in her new livery and was much photographed whilst on static display at Horsted Keynes following movement up from Sheffield Park as part of the cavalcade. -

Steam Railway

STEAM RAILWAY VENTURES IN SANDOWN 1864 - 1879 - 1932 - 1936 - 1946 - 1948 - 1950 When a Beyer Peacock 2-4-0 locomotive entered the newly built Sandown Railway Station on August 23rd 1864, it was the first steam passenger train to grace the town. It is more than probable that many local people had never seen the likes of it before, even more unlikely was that many of them would ride on one, as the cost of railway travel was prohibitive for the working class at the time. The Isle of Wight Railway ran from Ryde St. Johns Road to Shanklin until 1866 when the extension to Ventnor was completed. The London & South Western Railway in conjunction with the London Brighton & South Coast Railway, joined forces to build the Railway Pier at Ryde and complete the line from Ryde St. Johns to the Pier Head in 1880. The line to Ventnor was truncated at Shanklin and closed to passengers in April 1966, leaving the 8½ miles that remains today. On August 23rd 2008 the initial section will have served the Island for 144 years, and long may it continue. The Isle of Wight Railway, in isolation on commencement from the Cowes and Newport Railway (completed in 1862) were finally connected by a branch line from Sandown to Newport in 1879. Curiously named, the Isle of Wight Newport Junction Railway, it ran via Alverstone, Newchurch, Merstone, Horringford, Blackwater and Shide. Never a financial success, it served the patrons of the line well, especially during the war years, taking hundreds of workers to the factories at East and West Cowes. -

Neolithic & Early Bronze Age Isle of Wight

Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Resource Assessment The Isle of Wight Ruth Waller, Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service September 2006 Inheritance: The map of Mesolithic finds on the Isle of Wight shows concentrations of activity in the major river valleys as well two clusters on the north coast around the Newtown Estuary and Wooton to Quarr beaches. Although the latter is likely due to the results of a long term research project, it nevertheless shows an interaction with the river valleys and coastal areas best suited for occupation in the Mesolithic period. In the last synthesis of Neolithic evidence (Basford 1980), it was claimed that Neolithic activity appears to follow the same pattern along the three major rivers with the Western Yar activity centred in an area around the chalk gap, flint scatters along the River Medina and greensand activity along the Eastern Yar. The map of Neolithic activity today shows a much more widely dispersed pattern with clear concentrations around the river valleys, but with clusters of activity around the mouths of the four northern estuaries and along the south coast. As most of the Bronze Age remains recorded on the SMR are not securely dated, it has been difficult to divide the Early from the Late Bronze Age remains. All burial barrows and findspots have been included within this period assessment rather than the Later Bronze Age assessment. Nature of the evidence base: 235 Neolithic records on the County SMR with 202 of these being artefacts, including 77 flint or stone polished axes and four sites at which pottery has been recovered. -

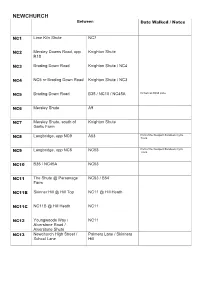

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes NC1 Lime Kiln Shute NC7 NC2 Mersley Downs Road, opp Knighton Shute R18 NC3 Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC4 NC4 NC5 nr Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC3 NC5 Brading Down Road B35 / NC10 / NC45A Known as Blind Lane NC6 Mersley Shute A9 NC7 Mersley Shute, south of Knighton Shute Garlic Farm Langbridge, opp NC9 A53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC8 Track Langbridge, opp NC8 NC53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC9 Track NC10 B35 / NC45A NC53 NC11 The Shute @ Parsonage NC53 / B54 Farm NC11B Skinner Hill @ Hill Top NC11 @ Hill Heath NC11C NC11B @ Hill Heath NC11 NC12 Youngwoods Way / NC11 Alverstone Road / Alverstone Shute NC13 Newchurch High Street / Palmers Lane / Skinners School Lane Hill NC14 Palmers Lane Dyers Lane Path obstructed not walkable NC15 Skinners Hill Alverstone Road NC16 Winford Road Alverstone Road NC17 Alverstone Main Road, opp Burnthouse Lane / NC44 Alverstone squirrel hide NC42 / youngwoods Way NC18 Burnthouse Lane / NC44 SS48 NC19 Alverstone Road NC20 / NC21 NC20 Alverstone Road / SS54 @ Cheverton Farm Borthwood Copse Borthwood Lane campsite NC21 Alverstone Road NC19 / NC20 / NC21 NC22 Borthwood Lane, opp NC19 NC22A @ Embassy Way Sandown airport @ Beaulieu Cottages runway ________________ SS30 @ Scotchells Brook SS28 @ Sandown Air Port NC22A NC22 / NC22B @ Embassy NC22 / SS25 Way Scotchells Brook Lane / NC22 / NC22A Known as Embassy Way – Sandown NC22B airport NC23 @ Embassy Way NC23 Borthwood Lane, opp Scotchells Brook Lane / SS57 NC24 Hale Common (A3056) @ Winford -

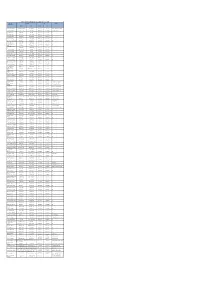

Location Address1 Address2 Address3 Postcode Asset Type

Location Address1 Address2 Address3 Postcode Asset Type Description Tenure Alverstone Land Alverstone Shute Alverstone PO36 0NT Land Freehold Alverstone Grazing Land Alverstone Shute Alverstone PO36 0NT Grazing Land Freehold Arreton Branstone Farm Study Centre Main Road Branstone PO36 0LT Education Other/Childrens Services Freehold Arreton Stockmans House Main Road Branstone PO36 0LT Housing Freehold Arreton St George`s CE Primary School Main Road Arreton PO30 3AD Schools Freehold Arreton Land Off Hazley Combe Arreton PO30 3AD Non-Operational Freehold Arreton Land Main Road Arreton PO30 3AB Schools Leased Arreton Land Arreton Down Arreton PO30 2PA Non-Operational Leased Bembridge Bembridge Library Church Road Bembridge PO35 5NA Libraries Freehold Bembridge Coastguard Lookout Beachfield Road Bembridge PO35 5TN Non-Operational Freehold Bembridge Forelands Middle School Walls Road Bembridge PO35 5RH Schools Freehold Bembridge Bembridge Fire Station Walls Road Bembridge PO35 5RH Fire & Rescue Freehold Bembridge Bembridge CE Primary Steyne Road Bembridge PO35 5UH Schools Freehold Bembridge Toilets Lane End Bembridge PO35 5TB Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge RNLI Life Boat Station Lane End Bembridge PO35 5TB Coastal Freehold Bembridge Car Park Lane End Forelands PO35 5UE Car Parks Freehold Bembridge Toilets Beach Road / Station Road Bembridge PO35 5NQ Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge Toilet High Street Bembridge PO35 5SE Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge Toilets High Street Bembridge PO35 5SD Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge -

Cattle Bulls, Baiting & Hard Cheese

f olkonwight Island Folk History Adapted from Cock & Bull Stories: Animals in Isle of Wight Folklore, Dialect and Cultural History (2008), by Alan R Phillips C ATTLE BULLS , BAITING & HARD CHEESE Numerous ox bones, many of which had been split open for the extraction of marrow, together with the teeth bones of a horse, were discovered in 1936 by Hubert Poole in a Mesolithic deposit on the east bank of the Newtown River. By the Iron Age dairy and b eef cattle together with sheep would have grazed the Island's meadows and oxen would have have been yoked to a wooden plough, or 'ard'. Courtesy of Isle of Wight Heritage Service Regarding the three - branched prehistoric flint implement known as a tribra ch, which has remained something of a mystery since its discovery most probably at Ventnor in the 1850s, Hubert Poole conjectured in 1941 that if displayed with its longer arm pointing downwards it bears a rough resemblance to the horned head of a bull, wh ich could conceivably have been mounted on a staff and carried in procession. This remains arguably still the best interpretation, though whether one would wish to concur with Poole that it might have been part of a phallic cult (all the rage in archaeolog ical circles when Poole was writing) is perhaps less likely. Poole went on to draw an analogy with the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes on the Island, which used to carry at an annual church parade a pair of bull's horns mounted on a staff in much th e same way that others carried a banner. -

ROAD OR PATH NAME from to from to Forest Road, Newport

ROAD AND PATH CLOSURES (10th August 2020 ‐ 16th August 2020) ROAD OR LOCATION DATE DETAILS PATH NAME FROM TO FROM TO Forest Road, Newport Hampshire Crescent Medina Way 14.08.2020 23.08.2020 Junction improvement works Chine Avenue, Shanklin Everton Lane High Street 14.08.2020 17.08.2020 Carriageway repairs High Street, Cowes Carvel Lane Sun Hill 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Town Quay, Cowes Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP High Street, Brading Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Quay Lane, Brading Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Seaview Lane, Nettlestone Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Surbiton Road, Ryde Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Upper Highland Road, Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Ryde Lower Highland Road, Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Ryde Lower Road, Brading Golf Links Road The Mall 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Upper Road, Brading Main Road Bullys Hill 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Zig Zag Road, Ventnor Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Bellevue Road, Ventnor Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Terrace Road, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Trafalgar Road, Newport Union Street New Street 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Bignor Place, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP Clarence Road, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 CIP York Road, Newport Entire length Entire length 14.08.2020 25.09.2020 -

Post-Medieval & Modern Isle of Wight

Post Med-Modern Period Owen Cambridge & Vicky Basford May 2007 1) Inheritance The post Medieval and modern period of the Isle of Wight is characterised by the enormous variation in the types of sites and landscapes. This period is perhaps the most dynamic in terms of the historically mapped social change and technological advances within the context of a rapidly changing socio-economic and political climate. The potential to understand the effects of industry, religion, politics and economics on shaping the landscape as a whole is a rare opportunity in archaeological terms but the advent of GIS and Historic Area Action Plans allows researchers unprecedented access to holistic data. Current political and social attitudes toward cultural heritage from this period are by no means consistent, on one hand regeneration of brown field sites is considered a priority and modern industrial heritage is seen to be an obstacle to economic regeneration but local interest in this period is increased over the last ten years at an exponential rate. The value of remains from the modern period inevitably reflect the changing research agendas of archaeologists and historians, the danger is that the true worth of those remains is only acknowledged in retrospect. Obvious gaps and biases: The most obvious bias when considering the evidence for this period comes from the archaeological investigations themselves. Excavation reports seldom explore the later cultural heritage and often dismiss material from this period as uninteresting. Until the recent English Heritage funded Extensive Urban Survey little systematic research had been conducted on the Island; the publication of the series of Extensive Urban Surveys does inevitably bias the information toward the Towns included in this works. -

Feasibility Study for Isle of Wight Railway Extension

Feasibility study for Isle of Wight railway extension July 6, 2021 A business case considering the re-opening of the railway between the existing Island Line and Newport has been submitted to the Department for Transport by the Isle of Wight Council. The authority, supported by Island MP Bob Seely, is seeking government support from the ‘Restoring Your Railway’ programme to further develop the case for reinstating some of the Islands’ lost rail links. The project will aim to reinstate the disused rail line between the Island Line and Newport, via Blackwater, providing a frequent, fast and reliable railway service from Ryde Pier Head to the Island’s county town. Councillor Phil Jordan, Cabinet member for transport and infrastructure, said extending the Island’s rail network had significant potential to boost the local economy while helping to ease congestion and reduce carbon emissions. He said: “Reinstating this rail link is vital to supporting the economic growth of our Island and to help reduce carbon emissions. It will provide a viable alternative to private car travel by improving journey times and connectivity. “We’ve submitted a strong case and hope the project will be successful in moving to the next stage. The government has previously signalled support for our ambitions and we’re hopeful they’ll help us progress this scheme further.” In May 2020, the council received up to £50,000 from the Restoring Your Railways programme to prepare a feasibility study for restoring former rail links between Newport and Ryde and Ventnor and Shanklin. In December 2020, the council appointed a consortium of organisations, led by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR Ltd), to prepare a Strategic Outline Business Case (SOBC) — an early feasibility study — and supporting work. -

Historic Environment Action Plan Arreton Valley

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan Arreton Valley Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service 0198 3 823810 Archaeology Unit @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for Arreton Valley INTRODUCTION This HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography, land use and settlement patterns which differentiate it from other HEAP areas. This HEAP identifies essential characteristics of the Arreton Valley HEAP Area as its open and exposed landscape with few native trees, its intensive agriculture and horticulture, its historic settlement patterns and buildings, and its valley floor pastures. The most significant features of this historic landscape, the most important forces for change, and key management issues are considered. Actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT Location, Geology and Topography • Geology is mainly Ferruginous Sands of the Lower Greensand Series with overlying Gravel Terraces in much of the area. Some Plateau Gravel deposits. Thin bands of Sandrock, Carstone, Gault and Upper Greensand along northern edge of area on boundary with East Wight Chalk Ridge . • Alluvium in river valleys. • Main watercourse is Eastern Yar which enters this HEAP Area at Great Budbridge and flows north east towards Newchurch. o Tributary streams flow into Yar. o The eastern side of the Yar Valley is crossed by drainage ditches to the south of Horringford. o Low-lying land to the east of Moor Farm and south of Bathingbourne has larger drainage canals • Land is generally below 50m OD with maximum altitude of 62m OD near Arreton Gore Cemetery. -

Location Address 1 Address 2 Location Postcode Asset Type

Location Address 1 Address 2 Location Postcode Asset Type Description Site Description Code Tenure Alverstone Grazing Land Alverstone Shute Alverstone PO36 0NT Grazing Land Alverstone Land at Alverstone Shute 02084 Freehold Appley Appley Beach Huts Esplanade Ryde PO33 1ND Esplanade, Parks & Gardens Ryde Appley Beach Huts 03190 Freehold Appley Beach area The Esplanade Ryde PO33 1ND Esplanade, Parks & Gardens Ryde Part of Beach at Appley M214 03267 Freehold Arreton Branstone Farm Study Centre Main Road Arreton PO36 0LT Education Non-Schools(Youth Centre, Residence etc) Arreton Branstone Farm Study Centre 00045 Freehold Arreton Stockmans House Main Road Arreton PO36 0LT Housing Arreton Stockmans House 00251 Freehold Arreton St George`s CE Primary School Main Road Arreton PO30 3AD Schools Arreton St George`s CE Primary School 00733 Freehold Arreton Land Off Hazley Combe Arreton PO30 3AD Non-Operational Arreton Land Adjacent Sewerage Works off Hazley Combe 01176 Freehold Arreton Land Garlic Festival Site Main Road Arreton PO36 0LT Non-Operational Arreton Land at Bathingbourne Site (Garlic Festival Site) 01821 Freehold Arreton Land Main Road Arreton PO30 3AB Schools Arreton Extra Playing Field Land adjacent School X0276 Leasehold Arreton Land Arreton Down Arreton PO30 2PA Non-Operational Arreton Land at Michael Moreys Hump X0277 Leasehold Bembridge Bembridge Library Church Road Bembridge PO35 5NA Libraries Bembridge Community Library 00028 Freehold Bembridge Coastguard Lookout Beachfield Road Bembridge PO35 5TN Non-Operational Bembridge Coastguard -

Compliments February 2020

Compliments February 2020 Clatterford Road, Carisbrooke – Customer wrote “Just a few lines to thank you for the resurfacing of Clatterford Road, my wife who is disabled was shown the utmost consideration and personal assistance by all of your conscientious staff when leaving and returning our house. The delay in finishing the roadworks, we now know was due to the insufficient supply of resurfacing material and what would have helped was if you had explained this on your Web Site. Once again thank you for the support of your employees and the prompt repainting of the disabled bay.” Bullen Road, Nettlestone – Customer wrote “Just to say thank you to the crew who cleared the fallen tree in Bullen Road last night. Not an easy job working in the pitch black with overhead cables. Fast, efficient and a job well done” Pallance Road, Gurnard – Customer wrote “just to say, thanks to the men doing the road sweeping; Pallance Road looks SO CLEAN!” Zig Zag Road, Ventnor – Customer called to say thank you for the work happening at the bottom of her road on Zig Zag road to repair the potholes, and that they are doing a brilliant job. Perowne Way, Sandown – Customer wrote “Thank you acting so quickly to my complaint” Cycle Track from Shanklin to Wroxall, Shanklin – Customer wrote “Please pass on my thanks to whoever swept the cycle path. It has been commented on by lots of dog walkers and cyclists, a great job, keep it up. Caws Avenue, Nettlestone – Customer called to say that he thought Island Roads did an amazing job resurfacing Caws Avenue and that we were very kind helping the elderly people in the area.