Drumgath Ladies Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newry & Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan

Newry & Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan Ulster Wildlife Trust watch Contents Foreword .................................................................................................1 Biodiversity in the Newry and Mourne District ..........................2 Newry and Mourne District Local Biodiversity Action Plan ..4 Our local priority habitats and species ..........................................5 Woodland ..............................................................................................6 Wetlands ..................................................................................................8 Peatlands ...............................................................................................10 Coastal ....................................................................................................12 Marine ....................................................................................................14 Grassland ...............................................................................................16 Gardens and urban greenspace .....................................................18 Local action for Newry and Mourne’s species .........................20 What you can do for Newry and Mourne’s biodiversity ......22 Glossary .................................................................................................24 Acknowledgements ............................................................................24 Published March 2009 Front Cover Images: Mill Bay © Conor McGuinness, -

Evaluation/Monitoring Report No 86. Aughnagun Road Milltown

Evaluation/Monitoring Report No 86. Aughnagun Road Milltown Mayobridge Co. Down AE/06/189 Ronan McHugh Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork Evaluation/Monitoring Report No. 86 Site Specific Information Site Address: Aughnagun Road, Milltown, Mayobridge, Co. Down Townland: Milltown SMR No.: Closest recorded sites is Dow 051:011 State Care Scheduled Other Grid Ref: J 1328 2840 County: Down Excavation Licence No: AE/06/189 Planning Ref / No.: P/2005/2445/F Date of Monitoring: 14th August 2006 Archaeologist Present. Ronan McHugh Brief Summary: The proposed development site is located in a field directly across a public roadway from a scheduled monument, the court tomb registered in the Northern Ireland Sites and Monuments Record as DOW 051:011. Three trenches were excavated to evaluate the potential impact of the proposed development on hidden archaeological remains. Nothing of archaeological significance was uncovered in any of the trenches. Type of monitoring: Excavation of three test trenches by mechanical excavator equipped with a grading bucket under archaeological supervision. Size of area opened: Three trenches were excavated. Two of these measured 50 metres x 2 metres. The third trench measured 25 metres x 2 metres. Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork Evaluation/Monitoring Report No. 86 Current Land Use: Pasture Intended Land Use: Residential Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork Evaluation/Monitoring Report No. 86 Background Archaeological evaluation was requested in response to application for outline planning permission for a single dwelling house in the townland of Milltown, less than 2 km south-south- east of Newry, Co. Down (Fig. 1). Fig 1. Location map showing approximate position of the development site (Circled in red) (Map supplied by EHS). -

Rathfriland Baptist Church February 2020

Monthly Bulletin Sunday Rotas February Meetings Rathfriland Baptist Door C/ Audio C/ Meeting Date Talk Church Men’s Thursday 20th at 8pm Church 2nd Andrew AP Snr Steven G Rachel P Bible Class Laura Good Every Tuesday at 6.45pm 9th John B Ian McC AP Snr Marcella News Club Sheila Women’s Saturday 8th at 12.30pm Meeting 16th John B John Kyle Julie T C.A.S.T. Sunday, 9th & 23rd Lydiard Victoria H The Well Saturday, 8th at 8pm 23rd Paul Johnny Caleb Fiona Omerod Charlene February 2020 “And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, (and we beheld His glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father,) full of grace and truth.’ John 1 v 14 Contact details: Contact Pastor Wilson: Rathfriland Baptist Church Telephone: 02840631117 Loughbrickland Road Mobile: 07904565635 Meetings Co. Down BT 34 5PZ E-mail: Sunday Services — 11:30am & 6:30pm Wednesday Night Audio Northern Ireland [email protected] Sunday School & Bible Class — 10:10am 5th 12th 19th 26th Please forward any information or details to Prayer Meeting — Wednesday at 8pm As 2nd As 9th As 16th As 23rd Judith, no later than the second Sunday in the month, for inclusion in the next bulletin. (Email to: [email protected],Tel: 07746713818) www.rathfrilandbaptist.com Meetings on The Lord’s Day CAST Dinner Ladies’ Event Date Details 9th Testimony Cameron Sharp (PM) 16th Testimony Peter Davidson (PM) 23rd Pastor Johnny Omerod Conference (AM/PM) You are invited to join us at 10am on Saturday 29th Feb (D.V) in Vic Gospel Concert Ryn, Lisburn for a prophetic Sincere Christian sympathy to: When—Saturday, 29th (doors conference. -

Slieve Donard Resort and Spa

The Present Day Over the past one hundred years the Slieve Donard has proved to be one of the finest and most luxurious hotels in Ireland, attracting guests from all over the world. The hotel celebrated its Centenary in 1997, and also achieved its 4 star status in that year. Over the years many additions and developments have been undertaken at the hotel; the addition of new Resort bedrooms and a magnificent new Spa in 2006 being the most significant in its history. The History of the Slieve Donard Resort and Spa Famous Guests For over a century the hotel has witnessed a massive ensemble of VIPS and Celebrities who have enjoyed the chic style and hospitality of ‘The Slieve’. Former guests at the hotel include: Percy French: Charlie Chaplin: King Leopold (of Belgium): Alan Whicker: Judith Chalmers: Dame Judi Dench: Angela Rippon: Sir Alf Ramsey: Jack Charlton: Frank Bough: Daniel O’Donnell to name but a few. In more recent times they’ve also had visits from Eamonn Holmes: Archbishop Tutu: Michael Jordan: Tiger Woods: Michael Douglas: Catherine Zeta Jones: Lee Janzen: Jack Nicklaus: Gary Player: Arnold Palmer and The Miami Dolphins. A little known fact is that even before the hotel was built it generated Slieve Donard Resort and Spa, Downs Road, interest. In 1897 the Duke and Duchess of York, during a royal visit to Newcastle, County Down, BT33 0AH Newcastle, inspected the construction site as part of their tour. T. +44 (0) 28 4372 1066 E. [email protected] hastingshotels.com Introduction The Decor The Style Hastings Hotels purchased the Slieve Donard Hotel in 1972 together with five The Slieve Donard typified the ideas of Victorian grandeur and luxury with its From the very beginning the Slieve was intended to be a place to relax, be other Railway hotels, including the Midland in Belfast, the Great Northern in Drawing Room, Grand Coffee Room, Reading and Writing Room, Smoking entertained and pursue leisurely activities. -

The Concise Dictionary A-Z

The Concise Dictionary A-Z Helping to explain Who is responsible for the key services in our district. In association with Newry and Mourne District Council www.newryandmourne.gov.uk 1 The Concise Dictionary Foreword from the Mayor Foreword from the Clerk As Mayor of Newry and Mourne, I am delighted We would like to welcome you to the third to have the opportunity to launch this important edition of Newry and Mourne District Council’s document - the Concise Dictionary, as I believe Concise Dictionary. it will be a very useful source of reference for all Within the Newry and Mourne district there our citizens. are a range of statutory and non-statutory In the course of undertaking my duties as organisations responsible for the delivery a local Councillor, I receive many calls from of the key services which impact on all of our citizens regarding services, which are not our daily lives. It is important that we can directly the responsibility of Newry and Mourne access the correct details for these different District Council, and I will certainly use this as organisations and agencies so we can make an information tool to assist me in my work. contact with them. We liaise closely with the many statutory This book has been published to give you and non-statutory organisations within our details of a number of frequently requested district. It is beneficial to everyone that they services, the statutory and non-statutory have joined with us in this publication and I organisations responsible for that service and acknowledge this partnership approach. -

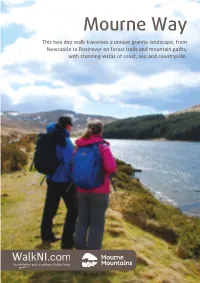

Mourne Way Guide

Mourne Way This two day walk traverses a unique granite landscape, from Newcastle to Rostrevor on forest trails and mountain paths, with stunning vistas of coast, sea and countryside. Slieve Commedagh Spelga Dam Moneyscalp A25 Wood Welcome to the Tollymore B25 Forest Park Mourne Way NEWCASTLE This marvellously varied, two- ROSTREVOR B8 Lukes B7 Mounatin NEWCASTLE day walk carries you from the B180 coast, across the edge of the Donard Slieve Forest Meelmore Mourne Mountains, and back to Slieve Commedagh the sea at the opposite side of the B8 HILLTOWN Slieve range. Almost all of the distance Hen Donard Mounatin Ott Mounatin is off-road, with forest trails and Spelga mountain paths predominating. Dam Rocky Lough Ben Highlights include a climb to 500m Mounatin Crom Shannagh at the summit of Butter Mountain. A2 B25 Annalong Slieve Wood Binnian B27 Silent Valley The Mourne Way at Slieve Meelmore 6 Contents Rostrevor Forest Finlieve 04 - Section 1 ANNALONG Newcastle to Tollymore Forest Park ROSTREVOR 06 - Section 2 Tollymore Forest Park to Mourne Happy Valley A2 Wood A2 Route is described in an anticlockwise direction. 08 - Section 3 However, it can be walked in either direction. Happy Valley to Spelga Pass 10 - Section 4 Key to Map Spelga Pass to Leitrim Lodge SECTION 1 - NEWCASTLE TO TOLLYMORE FOREST PARK (5.7km) 12 - Section 5 Leitrim Lodge to Yellow SECTION 2 - TOLLYMORE FOREST PARK TO HAPPY VALLEY (9.2km) Water Picnic Area SECTION 3 - HAPPY VALLEY TO SPELGA PASS (7km) 14 - Section 6 Yellow Water Picnic Area to SECTION 4 - SPELGA PASS TO LEITRIM LODGE (6.7km) Kilbroney Park SECTION 5 - LEITRIM LODGE TO YELLOW WATER PICNIC AREA (3.5km) 16 - Accommodation/Dining The Western Mournes: Hen Mountain, Cock Mountain and the northern slopes of Rocky Mountain 18 - Other useful information SECTION 6 - YELLOW WATER PICNIC AREA TO KILBRONEY PARK (5.3km) 02 | walkni.com walkni.com | 03 SECTION 1 - NEWCASTLE TO TOLLYMORE FOREST PARK NEWCASTLE TO TOLLYMORE FOREST PARK - SECTION 1 steeply now to reach the gate that bars the end of the lane. -

Curates of Clonallon Who Resided in Mayobridge, Prior to the Formation of a New Parish

CURATES OF CLONALLON WHO RESIDED IN MAYOBRIDGE, PRIOR TO THE FORMATION OF A NEW PARISH Reverend Fr Mooney The Revd Fr. Mooney was the first resident Curate in Mayobridge. He lived in the old Church of Ireland Vicarage until a new Parochial House was built by the Revd Fr. McMullan about the 1870s. He was a nephew of Fr. John Mooney, who was P.P. of Annaclone, and educated for the Priesthood at Maynooth. He was ordained in Newry by the Most Revd Dr. Blake in 1854. Having served the people of Mayobridge for 17 years, he was appointed Parish Priest of Annaclone in 1876 and he died on the 3rd September 1889. Before arriving in Mayobridge, he served as Curate in Banbridge from 1854 until 1856 and in Dromara from 1856 until 1859. His remains are buried in Magheral. Reverend Fr Matthew Lynch The Revd Fr. Matthew Lynch replaced him in Mayobridge where he served from 1876 until 1881. Born in the Parish of Drumgath, he studied Ethics at Violet Hill Newry and from there, entered the Irish College at Salamanca in 1862, and commenced his Theological Studies in 1863. He was ordained by Dr. Leahy in Newry Cathedral on 18th August 1867. He was appointed to Dromara, as Curate in 1868 and served there until July 1869, when he was transferred to Annaclone. Having served there until July 1876, he was then appointed Curate in Mayobridge where he stayed until November 1881. On the 13th November 1881, he became P.P. of Aghaderg and on 26th April 1890 he was appointed P.P. -

Announcements for Sunday 19Th May 2019

Announcements for Sunday 19th May 2019 Minister Jesus said, “A city on a hill cannot be hidden… Rev Trevor Boyd, Dip. Min. in the same way, let your light shine before men, that The Manse 13 Redbridge Road, they may see your good deeds and praise your Father Rathfriland, in heaven.” BT34 5AH Matthew 5: 14 &16 028 406 30272 079 5510 2923 We exist as a congregation:- COMMITTED to the weekly worship of the Lord www.1strathfriland.co.uk DEDICATED to learning and obeying the Word of God MOTIVATED to witness to our Community by Word and www.facebook.com/FirstRathfriland Action that JESUS is the only way to SALVATION @1stRathfrilandP Welcome in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ. We have come together to worship God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, upon whom we depend for everything, and who blesses us daily by his grace. Today: Sunday 19th May 2019 11:00am Prayer Meeting in Morrison Room 11:30am Loyal Friends. 1 Samuel 19: 1-24—Rev. Boyd 6.30pm Prayer Meeting in Choir Room. 7.00pm Gospel at a river, Acts 16: 6-15—Rev. Boyd Next Sunday 26th May 11.00am Prayer Meeting in Morrison Room 11.30am Promises, 1 Samuel 20; 1-16 6.30pm Prayer Meeting in Choir Room 7.00pm Gospel on the Street, Acts 16: 16-23—Rev. Boyd On Wednesday 22nd May in the Church Hall the Rev. Boyd will give a talk on his Sabbatical trip to London and the islands of Harris and Lewis in the Hebrides. There will be photos, some short video clips, Psalm singing and an opportunity for questions. -

Planning Applications Decisions Issued

Planning Applications Decisions Issued From: 25/05/2020 To: 31/05/2020 No. of Applications: 44 Reference Number Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Date Application Time to Decision Status Process Issued (Weeks) LA07/2017/1122/F Mr Thomas Small 57 Lands approximately 90m Provision of storage shed 29/05/2020 PERMISSION 141.8 Chancellors Road south of 57 Chancellors Road associated with established GRANTED Altnaveigh Altnaveigh economic development use Newry Newry (use class B4) including associated site works and landscaping LA07/2018/0037/F Marie and Eugene Millar 23 24a Kilbroney Road Proposed replacement 29/05/2020 PERMISSION 120.6 Park Lane Rostrevor dwelling REFUSED Rostrevor BT34 3BJ Warrenpoint LA07/2018/0649/F Jim Magill 75 Creagh Road Lands 320m north of 7 Glen Replacement of existing wind 29/05/2020 PERMISSION 103.6 Tempo Road turbine approved under GRANTED BT94 3FZ Drummiller application P/2010/0931/F, Newry changing 30m hub height to Co. Down 40m and 27m rotor diameter to 39m rotor diameter LA07/2019/0455/O Gerard Hanna 2 Carnacavill Lands between 4 and 10 Infill site for 2 dwellings 26/05/2020 PERMISSION 58.4 Road Ballyhafry Road GRANTED Castlewellan Newcastle BT31 9HB Page 1 of 10 Planning Applications Decisions Issued From: 25/05/2020 To: 31/05/2020 No. of Applications: 44 Reference Number Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Date Application Time to Decision Status Process Issued (Weeks) LA07/2019/0683/F Mr Steven Nicholson 71 Land approx. 300m west of 44 Proposed free range poultry 29/05/2020 PERMISSION 54.2 Aughnagurgan Road Blaney Road shed with 2no feed bins and GRANTED Newtownhamilton Newtownhamilton associated site works (Poultry BT35 0DZ shed to contain 16,000 free range egg laying hens) LA07/2019/0824/F Francis Annett 7 to the rear of No 78 Proposed farm store for hay, 29/05/2020 PERMISSION 51.4 Brackenagh West Road Carrigenagh Road machinery and veterinary REFUSED Ballymartin Kilkeel inspections BT34 4PW BT34 4PZ LA07/2019/0858/F Mr Richard Murphy 21 Land approx. -

Drumgath Ladies Group

Survey Report No. 62 Harry Welsh and David Craig Drumgath Ladies Group Drumgath Graveyard Drumgath County Down 2 © Ulster Archaeological Society 2017 Ulster Archaeological Society c/o School of Natural and Built Environment The Queen’s University of Belfast Belfast BT7 1NN Cover illustration: Graveyard survey 30 July 2017 _____________________________________________________________________ 3 CONTENTS List of figures 4 1. Summary 5 2. Introduction 7 3. The 29 July 2017 UAS Survey 7 4. Discussion 10 5. Recommendations for further work 13 6. Bibliography 13 Appendices A. Photographic record 14 B. Headstones database 18 4 LIST OF FIGURES Figures Page 1. Location map for Drumgath 5 2. Aerial view of the monument, looking south 6 3. Drone image of the site, north to the top of the image 8 4. Drone image of the site with hillshade applied, north to the top 9 5. Profile drawing of the enclosure (south-west/north-east) 9 6. UAS Survey Group members at work at Drumgath 10 7. Headstone with cross inscription 11 8. Cross-shaped grave marker or possible wayside cross 11 9. Typical granite block grave marker 12 5 1. Summary 1.1 Location A site survey was undertaken at a graveyard at Drumgath, County Down on Saturday 29 July 2017. This survey was undertaken to detail some of the many interesting headstones and other features that were visible within an early medieval enclosure, previously surveyed by the Ulster Archaeological Society (Stevenson and Scott 2017). The survey was the fifth in a series of planned surveys undertaken by members of the Ulster Archaeological Society during 2017. -

Speeding in E District for 10 Years

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION REQUEST Request Number: F-2015-02079 Keyword: Operational Policing Subject: Speeding In E District For 10 Years Request and Answer: Question 1 Can you tell us how many people have been caught speeding on the 30mph stretch of the A51 Madden Road near Tandragee Road in the past three years and how many accidents have occurred on this road in the past 10 years? Answer The decision has been taken to disclose the located information to you in full. All data provided in answer to this request is from the Northern Ireland Road Safety Partnership (NIRSP). Between January 2012 and May 2015, 691 people have been detected speeding on the A51 Madden Road, Tandragee. There have been 8 collisions recorded on the Madden Road between its junction with Market Street and where the Madden Road/Tandragee Road meets Whinny Hill. This is for the time period 1st April 2005 to 31st March 2015. One collision resulted in a fatality, one resulted in serious injury and 6 resulted in slight injuries. Question 2 Also can you provide figures for the average amount of speeders caught per road in E district? Clarification Requested: Would you be happy with those sites identified as having met the criteria for enforcement at 30mph by the NIRSP in the new district of ‘Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon’? I have provided a list below. Please let me know how you wish to proceed. Madden Road, Tandragee Monaghan road, Middletown village, Armagh Kilmore Road, Richhill, Armagh Whinny Hill, Gilford Donaghcloney Road, Blackskull Hilltown Road, Rathfriland Banbridge Road, Waringstown Main Street, Loughgall Scarva Road, Banbridge Banbridge Road, Kinallen Kernan Road, Portadown A3 Monaghan Road Armagh Road, Portadown Portadown Road, Tandragee Clarification Received: Yes I would be happy with those figures. -

The Down Rare Plant Register of Scarce & Threatened Vascular Plants

Vascular Plant Register County Down County Down Scarce, Rare & Extinct Vascular Plant Register and Checklist of Species Graham Day & Paul Hackney Record editor: Graham Day Authors of species accounts: Graham Day and Paul Hackney General editor: Julia Nunn 2008 These records have been selected from the database held by the Centre for Environmental Data and Recording at the Ulster Museum. The database comprises all known county Down records. The records that form the basis for this work were made by botanists, most of whom were amateur and some of whom were professional, employed by government departments or undertaking environmental impact assessments. This publication is intended to be of assistance to conservation and planning organisations and authorities, district and local councils and interested members of the public. Cover design by Fiona Maitland Cover photographs: Mourne Mountains from Murlough National Nature Reserve © Julia Nunn Hyoscyamus niger © Graham Day Spiranthes romanzoffiana © Graham Day Gentianella campestris © Graham Day MAGNI Publication no. 016 © National Museums & Galleries of Northern Ireland 1 Vascular Plant Register County Down 2 Vascular Plant Register County Down CONTENTS Preface 5 Introduction 7 Conservation legislation categories 7 The species accounts 10 Key to abbreviations used in the text and the records 11 Contact details 12 Acknowledgements 12 Species accounts for scarce, rare and extinct vascular plants 13 Casual species 161 Checklist of taxa from county Down 166 Publications relevant to the flora of county Down 180 Index 182 3 Vascular Plant Register County Down 4 Vascular Plant Register County Down PREFACE County Down is distinguished among Irish counties by its relatively diverse and interesting flora, as a consequence of its range of habitats and long coastline.