Staging the Sites of Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

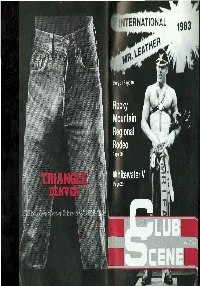

Clubscene-Jun83.Compressed.Pdf

C") Q) 0: oCl!, Q) c Q) (J (J) ..c ::l G Q) c Q) (J (J) ..c ::l G C\I Q) 0> oCl!, CONTENTS 5'. \-EP-"t"'e.;. _ • .cLUB ·--<-'r~. ..6"CENE •• ISSUE #11 '•. \~:l<i ~ ·~ l.{. ~"oj' Club News Pg. 8 International Mr. Leather '83 Pg. 16 Whitewater Weekend V Pg.23 J. Colt Thomas-International Mr. Leather '83 Rocky Mountain Regional Rodeo Pg.30 Sponsored by Officers Club-Houston Photo by I.M.L. Studios Club Calendar Pg.36 FOR THE ANIMAL OFFICES Kansas City IN YOU .... 3317 Montrose, Sui.te 1087 Burt Holderman (816)587·9941 Houston, Texas 77006 Minneapolis (713) 529-7620 Dan VanGuilder. (612) 872·9218 New Orleans PUBLISHERS .... .Alan LipkinlDan Mciver Wally Sherwood (504) 368-1805 Phoenix EDITOR .. .. Gerry "G. w." Webster Jerry Zagst (602) 266-2287 ART DIRECTOR. .... .Ty Davison FEATURE WRITERS TYPESETTER .. .Lee Christensen Fledermaus (713) 466-3224 Courtesy of Dungeon Master REPRESENTATIVE·AT·LARGE .Bill Green OFFICIALLY SANCTION ED ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Mid·America Conference of Clubs Dan Mciver (713) 529-7620 ADVERTISING AND EDITORIAL Atlanta Dale Scholes (404) 284·4370 The official views of this newsmagazine are expressed only in editorials. Opinions expressed in by-lined cot- (404) 872-0209 umns,letters and cartoons are those of the.wrlters and Chicago artists and do not necessarily represent the opinions Chuck Kiser. (312) 751·1640 of CLUB SCENE. Cleveland Publication of the name or photograph of any person or Tony Silwaru & organization in articles or advertising in CLUB SCENE Ron Criswell (216) 228·2631 is not to be construed as any indication of the sexual Corpus Christi orientation of such person or organization. -

Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: an Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives Among Leathermen

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 5-2020 Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen University of Oklahoma, [email protected] Trenton M. Haltom University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Worthen, Meredith G. F. and Haltom, Trenton M., "Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen" (2020). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 707. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/707 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. digitalcommons.unl.edu Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen1 and Trenton M. Haltom2 1 University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA; 2 University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA Corresponding author — Meredith G. F. Worthen, University of Oklahoma, 780 Van Vleet Oval, KH 331, Norman, OK 73019; [email protected] ORCID Meredith G. F. Worthen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6765-5149 Trenton M. Haltom http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1116-4644 Abstract The Fifty Shades books and films shed light on a sexual and leather-clad subculture predominantly kept in the dark: bondage, discipline, submission, and sadomasoch- ism (BDSM). -

Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 3-24-2016 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Barry, Todd, "From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1041. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1041 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 This dissertation examines how theatre and law have worked together to produce and regulate gay male lives since the 1895 Oscar Wilde trials. I use the term “gay legal theatre” to label an interdisciplinary body of texts and performances that include legal trials and theatrical productions. Since the Wilde trials, gay legal theatre has entrenched conceptions of gay men in transatlantic culture and influenced the laws governing gay lives and same-sex activity. I explore crucial moments in the history of this unique genre: the Wilde trials; the British theatrical productions performed on the cusp of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act; mainstream gay American theatre in the period preceding the Stonewall Riots and during the AIDS crisis; and finally, the contemporary same-sex marriage debate and the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). The study shows that gay drama has always been in part a legal drama, and legal trials involving gay and lesbian lives have often been infused with crucial theatrical elements in order to legitimize legal gains for LGBT people. -

Mr. Mid-Atlantic Leather Weekend 2018 Mr. MAL 2018 Contest Judges

Mr. Mid-Atlantic Leather Weekend 2018 Mr. MAL 2018 Contest Judges Martel Brown Mr. Mid-Atlantic Leather 2017 Continuing the Pittsburgh legacy, Martel became the 5th Mr. Pittsburgh Leather Fetish to win the title of Mr. Mid-Atlantic Leather. As a proud member of The Three Rivers Leather Club he has made it his mission to bridge the gap between the sometimes-distant subcultures within the gay community. In this way, he embraces his individuality in such a way that others are encouraged to find their own truth in their kinkster identities. Leading by example, your reigning Mr. Mid-Atlantic Leather has called out to the leather community to recognize how their umbrella extends to all marginalized kinksters that we all belong under an umbrella of leather and fetish as a community of sex-positive persons that embrace diversity while building a mosaic of micro communities within it that honor our differences, yet recognize our best traditions. Once you see his smile, you'll feel the weight of his sincerity and his promise to break down stereotypes, breakthrough barriers of prejudice, and to support the mentoring and creation of tomorrow's kinkster leaders that follow in all our courageous past leader's footsteps. Ralph Bruneau International Mr. Leather 2017 Ralph Bruneau competed at IML as Mr. GNI Leather 2016 representing Gay Naturists International, the largest naturist organization in the world. He began his leather journey in 1974 at the legendary Mineshaft in NYC. In his first career, he was an actor on Broadway and on television creating the role of Mike Doonesbury in the Broadway musical Doonesbury and appearing on TV in shows from soaps to Seinfeld. -

Submission for the Inquiry Into the Harm Being Done to Australian Children Through Access to Pornography on the Internet

Jàguar Lacroix 9th March 2016 1 Submission for the Inquiry into the harm being done to Australian children through access to pornography on the internet Jàguar Lacroix MAPs, Grad. Dip. Psych., Grad Dip. Coun, ADOM Animal Rights, Human Rights Activist; Doctoral candidature pending (2016) Thank you for this opportunity to express my thoughts and ideas. It is my hope that they make a constructive contribution to the debate. Jàguar Lacroix 9th March 2016 2 Submission for the Inquiry into the harm being done to Australian children through access to pornography on the internet "During times of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act." George Orwell When legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon (19931) wrote that, we live in a porn saturated world I thought she was exaggerating. Upon educating myself on this subject I find she could not have been more correct. In fact pornographic imagery is increasingly emulated in fashion, advertising, celebrity blogs and in all forms of media (please see appendix A. for examples). Soft porn has gone mainstream, one wonders if hardcore, now accessible by any smartphone in a free wi-fi zone is soon to follow? March 8th, International Women’s Day 2016: Having read all seventeen current submissions to the Submission for the Inquiry into the harm being done to Australian children through access to pornography on the internet, I find that little can be added to the recommendations of Professor Freda Briggs or the heartfelt concerns of mothers and parents; I have therefor chosen in this submission to focus on causation or what I perceive to be the sociological origins and outcomes of pornography production and consumption. -

Public Sex, Queer Intimate Kinship, and How the AIDS Epidemic Bathhouse Closures Constituted a Dignity Taking

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 92 Issue 3 Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration Article 13 3-6-2018 Fucking With Dignity: Public Sex, Queer Intimate Kinship, and How the AIDS Epidemic Bathhouse Closures Constituted a Dignity Taking Stephen M. Engel Bates College Timothy S. Lyle Iona College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephen M. Engel & Timothy S. Lyle, Fucking With Dignity: Public Sex, Queer Intimate Kinship, and How the AIDS Epidemic Bathhouse Closures Constituted a Dignity Taking, 92 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 961 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol92/iss3/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. FUCKING WITH DIGNITY: PUBLIC SEX, QUEER INTIMATE KINSHIP, AND HOW THE AIDS EPIDEMIC BATHHOUSE CLOSURES CONSTITUTED A DIGNITY TAKING STEPHEN M. ENGEL* TIMOTHY S. LYLE** I. INTRODUCTION On Friday, March 11, 2016, just before Nancy Reagan’s funeral be- gan, Hillary Clinton offered an unprompted assessment of the former first- lady’s advocacy on AIDS: “It may be hard for your viewers to remember how difficult it was for people to talk about HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. And because of both President and Mrs. -

New York City by Jeffrey Escoffier

New York City by Jeffrey Escoffier Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Top: New York City in Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com 1848. Above: Times Square in As the cultural and economic capital of the United States, New York City has attracted 2006. Photograph by people from across the country and over the globe. Today, approximately one of every John Kolter. three New Yorkers was born outside the United States. The image of Times Square appears under the GNU Free Off and on over two centuries, New York City has also reigned as the capital of Documentation License. homosexual, transgender, and queer life in America. It has frequently provided an environment in which homosexuals, transgender, and other queer people have found their niche. No doubt, the percentage of glbtq people (by any definition) living in New York City far exceeds the conventional estimate for the population as a whole. Current estimates range from 750,000 to more than one million glbtq people living in New York City proper. But New York City, probably more than any other city in the country, is also the capital of sex. Walt Whitman celebrated this aspect of New York in his poetry. "City of orgies, walks and joys," he wrote, "as I pass O Manhattan your frequent and swift flash of eyes offering me love." New York City was the stage upon which millions of men and women realized desires--sexual, artistic, and commercial--that they could never have fulfilled in the small towns and provincial cities of America. -

Public Sex, Queer Intimate Kinship, and How the AIDS Epidemic Bathhouse Closures Constituted a Dignity Taking Stephen M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Chicago-Kent College of Law Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 92 Article 13 Issue 3 Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration 3-6-2018 Fucking With Dignity: Public Sex, Queer Intimate Kinship, and How the AIDS Epidemic Bathhouse Closures Constituted a Dignity Taking Stephen M. Engel Bates College Timothy S. Lyle Iona College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephen M. Engel & Timothy S. Lyle, Fucking With Dignity: Public Sex, Queer Intimate Kinship, and How the AIDS Epidemic Bathhouse Closures Constituted a Dignity Taking, 92 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 961 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol92/iss3/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUCKING WITH DIGNITY: PUBLIC SEX, QUEER INTIMATE KINSHIP, AND HOW THE AIDS EPIDEMIC BATHHOUSE CLOSURES CONSTITUTED A DIGNITY TAKING STEPHEN M. ENGEL* TIMOTHY S. LYLE** I. INTRODUCTION On Friday, March 11, 2016, just before Nancy Reagan’s funeral be- gan, Hillary Clinton offered an unprompted assessment of the former first- lady’s advocacy on AIDS: “It may be hard for your viewers to remember how difficult it was for people to talk about HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. -

Container List for the Allan Bérubé Papers

Container List Series I: Personal Papers. Series I.A Personal Papers: Biographical Information. 1946-2007 Physical Description: Box 1, folders 1-33; Box 179, folder 2 Arrangement: Arranged chronologically. Scope and Content Note: Includes Bérubé’s birth certificate, genealogical research, transcripts of his eulogies for his father and aunt, financial papers, Vietnam War draft papers and conscientious objector statements, real estate records and his obituaries. There is also documentation regarding illegal rent increases and an AIDS discrimination settlement concerning Bérubé’s partner Brian Keith. 1/1 Birth Certificate, 1946 1/2 Motor vehicle registration and driving school, 1966 1/3 Ronald Bérubé (Father’s) National Association of Broadcast Employees and Technicians (NABET) Union items, circa 1968 1/4-5 “My anti-war, CO papers” – conscientious objector status, American Friends Service Committee, circa 1968-1969 1/6 Check books, 1975-1976 1/7-8 125 Lyon Street Apartment, 1980 1/9 Business cards for stores, food, circa 1980-1990 1/10 Health [personal records, pamphlets], circa 1980-1983 1/11 ID cards, voter registration, memberships, circa 1980-1999 1/12 Dad, Shanti, Hospice, etc., circa 1981 1/13 126 Laguna: bills paid, legal correspondence, 1981-1985 1/14 “Dad article” – Father’s death, 1982 1/15 126 Laguna: legal agreement includes Brian Keith’s death, 1986-1988 1/16 848 Page St. papers, 1988 1/17 360 Guerrero Street, Dolores Plaza condominium purchase, 1988 1/18 N. Commonwealth Avenue apartment, Los Angeles, California, 1993 1/19 Jeannette -

The Thrill of Reinvention: Identity, Community, and Site

310 841H ACSA ANNUAL MEETING THEORY AND CRITICISM 1996 The Thrill of Reinvention: Identity, Community, and Site IRA TATTELMAN Washington, DC INTRODUCTION vistas and displacements. The relations between individual and social, discovery and difference, intervention and inter- This paper addresses the relationship between identity and action are explored. My proposal offers a space in which design. How is identity created and what are its physical gays and I would hope lesbians can organize socially and manifestations? I concentrate on spaces in which identities participate in the public sphere. are captured and expressed in physical terms, made visible through spatial production. As an example, marginalized TAKING IT TO THE STREETS people adopt and adapt marginalized sites and then, by directly engaging those sites, imbue them with meaning. This section explores the appropriation and interpretation of When sites are ordinary, problematic or contested, can one public space for collective and private use by gays and transform the complexity of social control and the details of lesbians(gj1). My research focuses on how sexual minorities interaction by examining and embracing one's political, approach the city street for cultural, social and political religious, sexual, etc. values? purposes. By examining the street's reuse and reprogram- As individuals, we exist at the intersection of many differ- ming during Pride celebrations, I discuss the ways individu- ent communities. Through our differences and struggles, we als and groups question the urban and architectural traditions organize together, adjusting to the institutional, cultural and which can constrain them. psychological forces that influence decisions. Design actions GIL's are all too familiar with movement and the longing are a result of these experiences, structures and settings. -

RECONSIDERING the PLAYS of ROBERT CHESLEY Rebecca Lynn Gavrila, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ‘THAT WASN’T JUST A PARTY:’ RECONSIDERING THE PLAYS OF ROBERT CHESLEY Rebecca Lynn Gavrila, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Dissertation Directed by: Dr. Faedra Chatard Carpenter School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies “That Wasn’t Just A Party: Reconsidering The Plays of Robert Chesley” is a reclamation project that is placing Robert Chesley as a significant voice of Gay and Sexual Liberation in the Post-Stonewall gay theatrical canon. As the majority of his plays were both unproduced and unpublished, this project serves to introduce a contemporary, mainstream audience to the dramatic writings of Robert Chesley. Chesley is best known for writing the first full-length AIDS play to be produced in the United States, Night Sweats. Unlike his contemporaries, Larry Kramer and William Hoffman, Chesley never saw his work cross-over into the commercial mainstream in part because of his commitment to staging graphic gay sex scenes. Sadly, Robert Chesley would become a victim of the AIDS crisis, dying in 1990. The political and artistic ideologies represented by Chesley’s works are currently under-acknowledged within the gay American theatre canon. By exploring Robert Chesley and the way his work addressed the ideals of Sexual Liberation I am contributing to the discourse of gay cultural criticism and gay theatre history. The current gay theatre canon lacks a figure that represented this political ideology within his theatrical texts. ‘THAT WASN’T JUST A PARTY:’ RECONSIDERING THE PLAYS OF ROBERT CHESLEY By Rebecca Lynn Gavrila Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 Advisory Committee: Dr. -

Queer Intimacies 1

Running head: QUEER INTIMACIES 1 Queer Intimacies: A New Paradigm for the Study of Relationship Diversity Phillip L. Hammack University of California, Santa Cruz David M. Frost University College London Sam D. Hughes University of California, Santa Cruz Author Note This manuscript was completed in part while the first author was supported by a Scholar Award from the William T. Grant Foundation and a Fellowship from the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. We grateful acknowledge Sari van Anders, three anonymous reviewers, and members of the Society for Personology, all of whom provided valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article. Correspondence may be addressed to Phillip L. Hammack, Department of Psychology, University of California, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 USA. Email: [email protected]. Manuscript accepted for publication (2018), Annual Review of Sex Research. QUEER INTIMACIES 2 Abstract Recognition of sexual and gender diversity in the twenty-first century challenges normative assumptions of intimacy that privilege heterosexual monogamy and the biological family unit, presume binary cisgender identities, essentialize binary sexual identities, and view sexual or romantic desire as necessary. We propose a queer paradigm to study relationship diversity grounded in seven axioms: intimacy may occur (1) within relationships featuring any combination of cisgender, transgender, or non-binary identities; (2) with people of multiple gender identities across the life course; (3) in multiple relationships simultaneously with consent; (4) within relationships characterized by consensual asymmetry, power exchange, or role play; (5) in the absence or limited experience of sexual or romantic desire; (6) in the context of a chosen rather than biological family; and (7) in other possible forms yet unknown.