Carbon Acquisition in Variable Environments: Aquatic Plants of the River Murray, Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WETLAND PLANTS – Full Species List (English) RECORDING FORM

WETLAND PLANTS – full species list (English) RECORDING FORM Surveyor Name(s) Pond name Date e.g. John Smith (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 (see your map) e.g. SP 1235 4325 (see your map) METHOD: wetland plants (full species list) survey Survey a single Focal Pond in each 1km square Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value using plants, by recording all wetland plant species present within the pond’s outer boundary. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from the extent of wetland vegetation (for example a ring of rushes growing at the pond’s outer edge), or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. After your survey please enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Stonewort, Bristly (Chara hispida) Bistort, Amphibious (Persicaria amphibia) Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia) Stonewort, Clustered (Tolypella glomerata) Crystalwort, Channelled (Riccia canaliculata) Arrowhead, Canadian (Sagittaria rigida) Stonewort, Common (Chara vulgaris) Crystalwort, Lizard (Riccia bifurca) Arrowhead, Narrow-leaved (Sagittaria subulata) Stonewort, Convergent (Chara connivens) Duckweed , non-native sp. -

Floristic Account of Submersed Aquatic Angiosperms of Dera Ismail Khan District, Northwestern Pakistan

Penfound WT. 1940. The biology of Dianthera americana L. Am. Midl. Nat. Touchette BW, Frank A. 2009. Xylem potential- and water content-break- 24:242-247. points in two wetland forbs: indicators of drought resistance in emergent Qui D, Wu Z, Liu B, Deng J, Fu G, He F. 2001. The restoration of aquatic mac- hydrophytes. Aquat. Biol. 6:67-75. rophytes for improving water quality in a hypertrophic shallow lake in Touchette BW, Iannacone LR, Turner G, Frank A. 2007. Drought tolerance Hubei Province, China. Ecol. Eng. 18:147-156. versus drought avoidance: A comparison of plant-water relations in her- Schaff SD, Pezeshki SR, Shields FD. 2003. Effects of soil conditions on sur- baceous wetland plants subjected to water withdrawal and repletion. Wet- vival and growth of black willow cuttings. Environ. Manage. 31:748-763. lands. 27:656-667. Strakosh TR, Eitzmann JL, Gido KB, Guy CS. 2005. The response of water wil- low Justicia americana to different water inundation and desiccation regimes. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage. 25:1476-1485. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 49: 125-128 Floristic account of submersed aquatic angiosperms of Dera Ismail Khan District, northwestern Pakistan SARFARAZ KHAN MARWAT, MIR AJAB KHAN, MUSHTAQ AHMAD AND MUHAMMAD ZAFAR* INTRODUCTION and root (Lancar and Krake 2002). The aquatic plants are of various types, some emergent and rooted on the bottom and Pakistan is a developing country of South Asia covering an others submerged. Still others are free-floating, and some area of 87.98 million ha (217 million ac), located 23-37°N 61- are rooted on the bank of the impoundments, adopting 76°E, with diverse geological and climatic environments. -

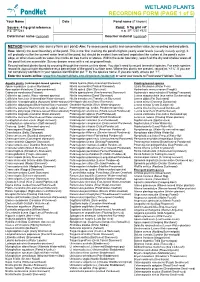

Pondnet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5)

WETLAND PLANTS PondNet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5) Your Name Date Pond name (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 e.g. SP 1235 4325 Determiner name (optional) Voucher material (optional) METHOD (complete one survey form per pond) Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value, by recording wetland plants. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from wetland vegetation like rushes at the pond’s outer edge, or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put ’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. Enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ or send your results to Freshwater Habitats Trust. Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Nitella hyalina (Many-branched Stonewort) Floating-leaved species Apium inundatum (Lesser Marshwort) Nitella mucronata (Pointed Stonewort) Azolla filiculoides (Water Fern) Aponogeton distachyos (Cape-pondweed) Nitella opaca (Dark Stonewort) Hydrocharis morsus-ranae (Frogbit) Cabomba caroliniana (Fanwort) Nitella spanioclema (Few-branched Stonewort) Hydrocotyle ranunculoides (Floating Pennywort) Callitriche sp. -

(Egeria Densa Planch.) Invasion Reaches Southeast Europe

BioInvasions Records (2018) Volume 7, Issue 4: 381–389 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.4.05 © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC This paper is published under terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (Attribution 4.0 International - CC BY 4.0) Research Article The Brazilian elodea (Egeria densa Planch.) invasion reaches Southeast Europe Anja Rimac1, Igor Stanković2, Antun Alegro1,*, Sanja Gottstein3, Nikola Koletić1, Nina Vuković1, Vedran Šegota1 and Antonija Žižić-Nakić2 1Division of Botany, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Marulićev trg 20/II, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 2Hrvatske vode, Central Water Management Laboratory, Ulica grada Vukovara 220, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3Division of Zoology, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Rooseveltov trg 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Author e-mails: [email protected] (AR), [email protected] (IS), [email protected] (AA), [email protected] (SG), [email protected] (VŠ), [email protected] (NK), [email protected] (AZ) *Corresponding author Received: 12 April 2018 / Accepted: 1 August 2018 / Published online: 15 October 2018 Handling editor: Carla Lambertini Abstract Egeria densa is a South American aquatic plant species considered highly invasive outside of its original range, especially in temperate and warm climates and artificially heated waters in colder regions. We report the first occurrence and the spread of E. densa in Southeast Europe, along with physicochemical and phytosociological characteristics of its habitats. Flowering male populations were observed and monitored in limnocrene springs and rivers in the Mediterranean part of Croatia from 2013 to 2017. -

Phenotypic Plasticity in Potamogeton (Potamogetonaceae )

Folia Geobotanica 37: 141–170, 2002 PHENOTYPIC PLASTICITY IN POTAMOGETON (POTAMOGETONACEAE ) Zdenek Kaplan Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-252 43 Prùhonice, Czech Republic; fax +420 2 6775 0031, e-mail [email protected] Keywords: Classification, Cultivation experiments, Modification, Phenotype, Taxonomy, Variability, Variation Abstract: Sources of the extensive morphological variation of the species and hybrids of Potamogeton were studied, especially from the viewpoint of the stability of the morphological characters used in Potamogeton taxonomy. Transplant experiments, the cultivation of clones under different values of environmental factors, and the cultivation of different clones under uniform conditions were performed to assess the proportion of phenotypic plasticity in the total morphological variation. Samples from 184 populations of 41 Potamogeton taxa were grown. The immense range of phenotypic plasticity, which is possible for a single clone, is documented in detail in 14 well-described examples. The differences among distinct populations of a single species observed in the field were mostly not maintained when grown together under the same environmental conditions. Clonal material cultivated under different values of environmental factors produced distinct phenotypes, and in a few cases a single genotype was able to demonstrate almost the entire range of morphological variation in an observed trait known for that species. Several characters by recent literature claimed to be suitable for distinguishing varieties or even species were proven to be dependent on environmental conditions and to be highly unreliable markers for the delimitation of taxa. The unsatisfactory taxonomy that results when such classification of phenotypes is adopted is illustrated by three examples from recent literature. -

Download This PDF File

Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae Article ID: 901 DOI: 10.5586/asbp.901 ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER in FLORISTICS AND PLANT CONSERVATION Publication History Received: 2020-04-26 Differences in Potamogeton praelongus Accepted: 2021-02-02 Published: 2021-05-15 Morphology and Habitats in Europe Handling Editor 1 1* 1 Zygmunt Dajdok; University of Zuzana Kozelková , Romana Prausová , Zina Tomášová , Wrocław, Poland; Lenka Šafářová2 https://orcid.org/0000-0002- 1 8386-5426 Department of Biology, University of Hradec Králové, Hradec Králové, 500 03, Czech Republic 2East Bohemian Museum in Pardubice, Pardubice, 530 02, Czech Republic Authors’ Contributions * ZK and RP: collection of feld To whom correspondence should be addressed. Email: [email protected] data and their evaluation; ZT: collection of feld data; LŠ: statistical analyses Abstract One of the most southern European occurrences of Potamogeton praelongus is in Funding the Czech Republic (CR), with only one native population in the Orlice River The study was fnanced by grants from the Ministry of foodplain in Eastern Bohemia, the only surviving site from 10 Czech localities Education of the Czech Republic known 45 years ago. is species is critically endangered in the CR and needs to – PřF UHK No. 2112/2014, be actively protected with a rescue program. e number of P. praelongus sites 2111/2015, 2107/2016, increases along a latitudinal gradient, from Central to North Europe (CR, Poland, 2113/2018, 2115/2019 and by funds awarded by EEA/Norway Sweden, and Norway), and correlates with improving conditions (water and the Ministry of Environment transparency and nutrient content in water) for this species along this gradient. -

Download This PDF File

Vol. 76, No. 2: 151-163, 2007 ACTA SOCIETATIS BOTANICORUM POLONIAE 151 RARE AND THREATENED PONDWEED COMMUNITIES IN ANTHROPOGENIC WATER BODIES OF OPOLE SILESIA (SW POLAND) ARKADIUSZ NOWAK1, SYLWIA NOWAK1, IZABELA CZERNIAWSKA-KUSZA2 1 Department of Biosystematics Laboratory of Geobotany and Plant Conservation, University of Opole Oleska 48, 45-052 Opole, Poland 2 Department of Land Cover Protection, University of Opole (Received: May 14, 2006. Accepted: August 16, 2006) ABSTRACT The paper presents results of geobotanic studies conducted in anthropogenic water bodies like excavation po- nds, fish culture ponds, other ponds, dam reservoirs, ditches, channels and recreational pools incl. watering places in Opole Silesia and surroundings in the years 2002-2005. The research focused on occurrence of threatened and rare pondweed communities. As the result of the investigations of several dozen of water bodies, 28 localities of rare pondweed communities were documented by 75 phytosociological relevés. Associations of Potametum tri- choidis J. et R Tx. in R. Tx. 1965, Potametum praelongi Sauer 1937, P. alpini Br.-Bl. 1949, P. acutifolii Segal 1961, P. obtusifolii (Carst. 1954) Segal 1965 and P. perfoliati W. Koch 1926 em. Pass. 1964 were found as well as communities formed by Potamogeton berchtoldii, P. nodosus and P. pusillus. The study confirms that anthropogenic reservoirs could serve as last refugees for many threatened pondweed communities, which decline or even extinct in their natural habitats. The results indicate that man-made habitats could shift the range limits of threatened species and support their dispersal. The authors conclude that habitats strongly transformed by man are important factors in the natural syntaxonomical diversity protection and should not be omitted in strategies of nature conservation. -

Potamogeton ×Fluitans (P. Natans × P. Lucens) in the Czech Republic. II

Preslia, Praha, 74: 187–195, 2001 187 Potamogeton ×fluitans (P. natans × P. lucens) in the Czech Republic. II. Isozyme analysis Potamogeton ×fluitans (P. natans × P. lucens) v České republice. II. Analýza isozymů Zdeněk Kaplan, IvanaPlačková & JanŠtěpánek Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences, CZ-252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic, e-mail: [email protected] Kaplan Z., Plačková I. & Štěpánek J. (2002): Potamogeton ×fluitans (P. natans × P. lucens)inthe Czech Republic. II. Isozyme analysis. – Preslia, Praha, 74: 187–195. Evidence from isozyme electrophoresis confirmed previous hypothesis on the occurrence of interspecific hybridization between Potamogeton natans L. and P.lucens L. formulated on the basis of morphology and stem anatomy. Isozyme phenotypes of the morphologically intermediate plants were compared with those obtained from the putative parents growing in the same locality. P. natans and P. lucens differed consistently in at least 12 loci and possessed different alleles at 7 loci. The hybrid had no unique alleles and exhibited an additive “hybrid” isozyme pattern for all 7 loci that could be reliably analysed and where the parents displayed different enzyme patterns. Both true parental genotypes were detected among samples of plants of P.lucens and P.natans from the same locality. The hybrid plants represent a recent F1 hybrid generation resulting from a single hybridization event. Consistent differences in enzyme activity between submerged and floating leaves of P. natans and P. ×fluitans were observed in all interpretable enzyme systems. Keywords: Potamogeton, hybridization, isozymes, electrophoresis, enzyme activity Introduction Potamogeton ×fluitans Roth (P. natans L. × P. lucens L.) was recently discovered in NE Bohemia‚ as a new taxon for the Czech Republic (Kaplan 2001). -

HANDY GUIDE to AQUATIC PLANTS in IRELAND Waterlilies Duckweeds

HANDY GUIDE TO AQUATIC PLANTS IN IRELAND Floating: Nymphaea, Nuphar, Nymphoides, Potamogeton, Lemna Rooted rosettes: Isoetes, Lobelia, Littorella, Subularia Ribbon-leaves: Sagittaria, Stratiotes, Potamogeton, Sparganium Simple alternate: Potamogeton, Lagarosiphon, Persicaria, Fontinalis antipyretica Opposite pairs: Crassula, Callitriche, Simple whorls: Elodea (3), Egeria (4-6), Hydrilla (4-5) Elodea Ceratophyllum Hottonia Egeria Ranunculus Myriophyllum Lagarosiphon Utricularia Hippuris, Hydrilla Other Compound leaves: Apium inundatum (Bipinnate, fine hair like branches) Oenanthe aquatica (Tripinnate; narrow leaflets, becoming emergent and cow- parsley-like) Waterlilies Nuphar lutea (2ndry veins arising along midrib; Yellow flwrd; over-wintering leaves lettuce like, petiole angular) Nymphaea alba (2ndry veins arising from petiole; White flwrd; petiole round, margin entire) Nymphoides peltata (Yellow flwrd; margin scalloped). – an alien invasive species Hydrocharis morsus-ranae (white flwd; leaves small, thick, rounded, margin smooth) Duckweeds Lemna gibba (Fat duckweed – bead-like) Lemna minor (2-4 mm across) Lemna minuta (1 mm across) Lemna trisulca (Ivy-leaved, usually submerged, sitting on plants or sediment) Spirodela polyrhiza (4-5 mm across; 2-4 roots) Starworts Submerged leaves long and linear, floating leaves blunt, ovate Callitriche brutia (leaves expanded at tip and notched) Callitriche hamulata (leaves expanded at tip and notched) Callitriche hermaphroditica (fruits winged) Callitriche obtusangula Callitriche palustris Callitriche -

Past and Present Status of the Aquatic Plants of the Marshlands of Iraq

Marsh Bulletin 2(2006) 160-172 MARSH BULLETIN Amaricf_Basra [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Past and present status of the aquatic plants of the marshlands of Iraq A. R. A. Alwan Biology Department , College of Science , University of Basrah Abstract Inventory and distribution of the aquatic plants historically recorded in the marshlands of Iraq were presented. More than hundred species of aquatic and amphibian plants have originally been recorded in the marshes of Iraq and less than 50% of this were recently recollected in 2004-2005. Several important aquatic plants such as the characteristic water lilies (Goaiba in Arabic) Nymphoides indica and N. peltata , the insectivorous Utricularia australis and the Arrowhead Sagittaria sagitifolia are seem to be disappeared. Until know sixteen obligate hydrophytes are not found. Two exotic species, Tamarix ramosissima and T. brachystichas invaded the area. Eight main types of aquatic vegetation were been identified and described, of which Hydrilla community was a new type for Iraq. The present status of plant diversity and communities of the Iraqi marshes was compared with that mentioned in the past. 1-Introduction However their boundaries can not precisely be The marshes of Iraq are considered as the defined . The majority of the permanent largest ecosystem in the middle East and marshes lie in the LSM through which the Western Eurasia (Maltby 1944, UNEP 2001, lower reaches and distributaries of the Tigris Nicholson and Clark 2003, Hussain and Ali and Euphrates flow. The Iraqi marshlands 2006) ; They lie in the triangle between Amara, (often called Alahwar) divided into three major Basrah and Thiqar, in the Lower part of the marshes : Mesopotamia with a maximum length 210km 1- The Eastern marshes, or Hawaiza marshes south-north and 170km east-west (Al-Khatab situated east of Tigris (S.E. -

Vallisneria Spiralis) in the Netherlands

Knowledge document for risk analysis of the non-native Tapegrass (Vallisneria spiralis) in the Netherlands by F.P.L. Collas, R. Beringen, K.R. Koopman, J. Matthews, B. Odé, R. Pot, L.B. Sparrius, J.L.C.H. van Valkenburg, L.N.H. Verbrugge & R.S.E.W. Leuven Knowledge document for risk analysis of the non-nativeTapegrass (Vallisneria spiralis) in the Netherlands F.P.L. Collas, R. Beringen, K.R. Koopman, J. Matthews, B. Odé, R. Pot, L.B. Sparrius, J.L.C.H. van Valkenburg, L.N.H. Verbrugge & R.S.E.W. Leuven 15 November 2012 Radboud University Nijmegen, Institute for Water and Wetland Research Department of Environmental Science, FLORON & Roelf Pot Research and Consultancy Commissioned by Invasive Alien Species Team Office for Risk Assessment and Research Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation Series of Reports on Environmental Science The series of reports on Environmental Science are edited and published by the Department of Environmental Science, Institute for Water and Wetland Research, Radboud University Nijmegen, Heyendaalseweg 135, 6525 AJ Nijmegen, The Netherlands (tel. secretariat: + 31 (0)24 365 32 81). Reports Environmental Science nr. 416 Title: Knowledge document for risk analysis of the non-native Tapegrass (Vallisneria spiralis) in the Netherlands Authors: Collas, F.P.L., R. Beringen, K.R. Koopman, J. Matthews, B. Odé, R. Pot, L.B. Sparrius, J.L.C.H. van Valkenburg, L.N.H. Verbrugge & R.S.E.W. Leuven Cover photo: Tapegrass (Vallisneria spiralis) in a side-branch of the river Erft at Kasterer Mühlen, Northrhine-Westphalia, Germany (© Photo A. -

Aquatic Plants Checklist

CHECKLIST OF SUBMERGED AND FLOATING AQUATIC PLANTS - BEDS, OLD CAMBS, HUNTS, NORTHANTS AND PETERBOROUGH Scientific name Common Name Beds old Cambs Hunts Northants and Ellenberg P'boro N PLANTS WITH SIMPLE, MORE OR LESS LINEAR UNDERWATER LEAVES; FLOATING OR EMERGENT LEAVES MAY BE BROADER Linear leaves only Eleogiton fluitans Floating Club-rush absent rare very rare extinct 2 Juncus bulbosus Bulbous Rush very rare rare rare very rare 2 Lagarosiphon major Curly Waterweed occasional occasional very rare very rare 6 + Potamogeton acutifolius Sharp-leaved Pondweed absent absent absent extinct 6 Potamogeton berchtoldii Small Pondweed rare occasional rare occasional 5 Potamogeton compressus Grass-wrack Pondweed extinct rare rare occasional 4 + Potamogeton friesii Flat-stalked Pondweed very rare occasional rare very rare 5 Potamogeton obtusifolius Blunt-leaved Pondweed very rare absent absent rare 5 + Potamogeton pectinatus Fennel Pondweed frequent frequent frequent frequent 7 + Potamogeton pusillus Lesser Pondweed occasional occasional occasional occasional 6 Potamogeton trichoides Hairlike Pondweed extinct occasional very rare very rare or extinct 6 Ruppia cirrhosa Spiral Tasselweed absent extinct absent absent 5 Zannichellia palustris Horned Pondweed occasional frequent occasional frequent 7 + Zostera marina Eelgrass absent very rare or extinct absent absent 6 Broad-leaved floating rosettes/leaves may be present Callitriche brutia ssp. hamulata Intermediate Water-starwort occasional absent very rare occasional 5 Callitriche obtusangula Blunt-fruited