Kasparek, Christopher, "Krystyna Skarbek: Re-Viewing Britain's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliografia Naukometryczno-Bibliometryczno

POLSKA AKADEMIA UMIEJĘTNOŚCI Tom XIV PRACE KOMISJI HISTORII NAUKI PAU 2015 Michał KOKOWSKI Instytut Historii Nauki im. Ludwika i Aleksandra Birkenmajerów Polskiej Akademii Nauk [email protected] BIBLIOGRAFIA NAUKOMETRYCZNO ‑BIBLIOMETRYCZNO‑ ‑INFORMETRYCZNA (WYBÓR) Streszczenie Przedstawiono wybór bibliografii z zakresu naukometrii, bibliometrii oraz infor metrii. Bibliografia została wyselekcjonowana w ramach autorskich badań prowadzonych w zakresie: a) aktualnej debaty na temat naukometrii, bibliometrii oraz informetrii w Pol sce, b) historii tych dyscyplin oraz c) historii naukoznawstwa. Zaletą takiego wyboru jest uwzględnienie wielu publikacji, które: a) przedstawiają poglądy zarówno polskich, jak i zagranicznych autorów; b) omawiają poważne ograni czenia metodyczne naukometrii, bibliometrii oraz informetrii; c) ukazują nierozerwalny związek tych dyscyplin z naukoznawstwem. Prezentowaną niżej bibliografię autor wykorzystał także w dwóch artykułach opubli kowanych w tomie 14. Prac Komisji Historii Nauki PAU (rok 2015). Słowa kluczowe: bibliografia, naukometria, bibliometria, informetria, metodologia naukometrii, nadużycia metod naukometrycznych, naukoznawstwo, polityka naukowa, polskie i międzynarodowe standardy naukometrii ADLER Robert, EWING John, TAYLOR Peter 2008: Citation statistics: A report from the International Mathematical Union (IMU) in cooperation with the International Council of Industrial and Applied Mathemat ics (ICIAM) and the Institute of Mathematical Statistics (IMS). Available online: http://www.mathunion.org/fileadmin/IMU/Report/CitationStatistics.pdf. -

Eastern Europe, Literature, Postimperial Difference

Form and Instability 8flashpoints The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Founding Editor; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Nouri Gana (Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) A complete list of titles is on page 222. Form and Instability Eastern Europe, Literature, Postimperial Difference Anita Starosta northwestern university press ❘ evanston, illinois THIS BOOK IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A COLLABORATIVE GRANT FROM THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION. Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2016 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2016. All rights reserved. Digital Printing isbn 978-0-8101-3202-3 paper isbn 978-0-8101-3259-7 cloth Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. -

Notes and References Documents Held at the Public Record Office, London, Are Crown Copyright and Are Reproduced by Permission of the Controller Ofhm Stationery Office

Notes and References Documents held at the Public Record Office, London, are crown copyright and are reproduced by permission of the Controller ofHM Stationery Office. I NTRODUCTION Christopher Andrew and David Dilks I. David Dilks (ed.), The Diaries rifSir Alexander Cadogan O.M. 1938-1945 (Lon don , (971) , p. 21. 2. Interview with Professor Hinsley in Part 3 of the BBC Radio 4 documentary series 'T he Profession of Intelligence', written and presented by Christopher Andrew (producer Peter Everett); first broadcast 16 Aug 1981. 3. F. H. Hinsleyet al., British Intelligencein the Second World War (London, 1979-). The first two chapters of volume I contain a useful retrospect on the pre-war development of the intelligence community. Curiously, despite the publication of Professor Hinsley's volumes, the government has decided not to release the official histories commissioned by it on wartime counter-espionage and deception. The forthcoming (non-official) collection of essays edited by Ernest R. May, Knowing One's Enemies: IntelligenceAssessment before the Two World Wars (Princeton) promises to add significantly to our knowledge of the role of intelligence on the eve of the world wars. 4. House of Commons Education, Science and Arts Committee (Session 1982-83) , Public Records: Minutes ofEvidence, pp . 76-7. 5. Chapman Pincher, Their Trade is Treachery (London, 1981). Nigel West, A Matter of Trust: MI51945-72 (London, 1982). Both volumes contain ample evidence of extensive 'inside information'. 6. Nigel West , MI5: British Security Operations /90/-/945 (London, 1981), pp . 41, 49, 58. One of the most interesting studies of British peacetime intelligence which depends on a substantial amount of inside information is Antony Verrier's history of post-war British foreign policy , Through the Looking Glass (London, 1983) . -

HC Dissertation Final

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ________________ Date A Muslim Humanist of the Ottoman Empire: Ismail Hakki Bursevi and His Doctrine of the Perfect Man By Hamilton Cook Doctor of Philosophy Islamic Civilizations Studies _________________________________________ Professor Vincent J. Cornell Advisor _________________________________________ Professor Ruby Lal Committee Member _________________________________________ Professor Devin J. Stewart Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date A Muslim Humanist of the Ottoman Empire: Ismail Hakki Bursevi and His Doctrine of the Perfect Man By Hamilton Cook M.A. Brandeis University, 2013 B.A., Brandeis University, 2012 Advisor: Vincent J. Cornell, Ph.D. -

Polish Contribution to World War II - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:45 AM Polish Contribution to World War II from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Polish contribution to World War II - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:45 AM Polish contribution to World War II From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The European theatre of World War II opened with the German invasion of Poland on Friday September 1, 1939 and the Soviet Polish contribution to World invasion of Poland on September 17, 1939. The Polish Army War II was defeated after more than a month of fighting. After Poland had been overrun, a government-in-exile (headquartered in Britain), armed forces, and an intelligence service were established outside of Poland. These organizations contributed to the Allied effort throughout the war. The Polish Army was recreated in the West, as well as in the East (after the German invasion of the Soviet Union). Poles provided crucial help to the Allies throughout the war, fighting on land, sea and air. Notable was the service of the Polish Air Force, not only in the Allied victory in the Battle of Britain but also the subsequent air war. Polish ground troops The personnel of submarine were present in the North Africa Campaign (siege of Tobruk); ORP Sokół displaying a Jolly the Italian campaign (including the capture of the monastery hill Roger marking, among others, at the Battle of Monte Cassino); and in battles following the the number of sunk or damaged invasion of France (the battle of the Falaise pocket; an airborne ships brigade parachute drop during Operation Market Garden and one division in the Western Allied invasion of Germany). Polish forces in the east, fighting alongside the Red army and under Soviet command, took part in the Soviet offensives across Belarus and Ukraine into Poland, across the Vistula and towards the Oder and then into Berlin. -

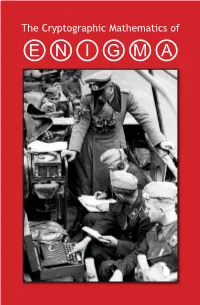

Revised Edition 2019 Dedicated to the Memory of the Allied Polish Cryptanalysts

The Cryptographic Mathematics of ⒺⓃⒾⒼⓂⒶ This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email your request to [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Color photographs, David S. Reynolds, NSA/CSS photographer Cover: General Heinz Guderian in armored command vehicle with an Engima machine in use, May/June 1940. German Federal Archive The Cryptographic Mathematics of Enigma Dr. A. Ray Miller Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency Revised edition 2019 Dedicated to the Memory of the Allied Polish Cryptanalysts Marian Rejewski Jerzy Rozycki Henryk Zygalski he Enigma cipher machine had the confidence of German forces who depended upon its security. This misplaced con- Tfidence was due in part to the large key space the machine provided. This brochure derives for the first time the exact number of theoretical cryptographic key settings and machine configura- tions for the Enigma cipher machine. It also calculates the number of practical key settings Allied cryptanalysts were faced with daily throughout World War II. Finally, it shows the relative contribution each component of the Enigma added to the overall strength of the machine. ULTRA [decrypted Enigma messages] was the great- est secret of World War II after the atom bomb. With the exception of knowledge about that weapon and the prob- able exception of the time and place of major operations, such as the Normandy invasion, no information was held more tightly…. -

Author(S) Naval Postgraduate School (U.S.) Title Catalogue for 1968-1970

Author(s) Naval Postgraduate School (U.S.) Title Catalogue for 1968-1970 Publisher Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School Issue Date 1968 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10945/31701 This document was downloaded on May 22, 2013 at 14:30:37 R, S****** NAM PIST1IIAII1ATI SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA CATALOGUE FOR 1968-1970 MM POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA CATALOGUE FOR 1968-1970 Paul Robert Ignatius Secretary of the Navy MISSION The Secretary of the Navy has defined the mission of the Naval Postgraduate School as follows: "To conduct and direct the Advanced Education of commissioned officers, and to provide such other technical and professional instruction as may be prescribed to meet the needs of the Naval Service; and in support of the foregoing, to foster and encourage a program of research in order to sustain academic excellence." Superintendent Robert Waring McNitt Rear Admiral, U.S. Navy B.S., Naval Academy, 1938; Naval Postgraduate School, 1945; M.S., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1947 Academic Dean Robert Fross Rinehart B.A., Wittenberg College, 1930; M.A., Ohio State Univ., 1932; Ph.D., 1934; D.Sc, Wittenberg Univ., 1960 b<3 a -a s © ; NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Deputy Superintendent for Operations and Programs Fletcher Harris Burnham Captain, U.S. Navy B.S., Naval Academy, 1943; B.S. in Operations Analysis, Naval Postgraduate School, 1954; M.S., 1954 Deputy Superintendent for Administration and Logistics Thomas Andrew Melusky Captain, U.S. Navy B.S., Univ. of Washington, 1941 M.A., George Washington Univ., 1963 Dean of Programs Wilbert Frederick Koehler B.S. Allegheny College, 1933; M.A., Cornell Univ., 1934; Ph.D., Johns Hopkins Univ. -

British Codebreaking Operations: 1938-43 Andrew J

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2015 All the King’s Men: British Codebreaking Operations: 1938-43 Andrew J. Avery East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Avery, Andrew J., "All the King’s Men: British Codebreaking Operations: 1938-43" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2475. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2475 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All the King’s Men: British Codebreaking Operations: 1938-43 _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _____________________ by Andrew J. Avery May 2015 _____________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Andrew L. Slap Dr. John Rankin Keywords: World War II, Alan Turing, Bletchley Park, Code-breaking, Room 40, Gordon Welchman, GC&CS ABSTRACT All the King’s Men: British Codebreaking Operations: 1938-43 by Andrew J. Avery The Enigma code was one of the most dangerous and effective weapons the Germans wielded at the outbreak of the Second World War. The Enigma machine was capable of encrypting radio messages that seemed virtually unbreakable. -

Creativity Anoiko 2011

Creativity Anoiko 2011 PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 27 Mar 2011 10:09:26 UTC Contents Articles Intelligence 1 Convergent thinking 11 Divergent thinking 12 J. P. Guilford 13 Robert Sternberg 16 Triarchic theory of intelligence 20 Creativity 23 Ellis Paul Torrance 42 Edward de Bono 46 Imagination 51 Mental image 55 Convergent and divergent production 62 Lateral thinking 63 Thinking outside the box 65 Invention 67 Timeline of historic inventions 75 Innovation 111 Patent 124 Problem solving 133 TRIZ 141 Creativity techniques 146 Brainstorming 148 Improvisation 154 Creative problem solving 158 Intuition (knowledge) 160 Metaphor 164 Ideas bank 169 Decision tree 170 Association (psychology) 174 Random juxtaposition 174 Creative destruction 175 References Article Sources and Contributors 184 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 189 Article Licenses License 191 Intelligence 1 Intelligence Intelligence is a term describing one or more capacities of the mind. In different contexts this can be defined in different ways, including the capacities for abstract thought, understanding, communication, reasoning, learning, planning, emotional intelligence and problem solving. Intelligence is most widely studied in humans, but is also observed in animals and plants. Artificial intelligence is the intelligence of machines or the simulation of intelligence in machines. Numerous definitions of and hypotheses about intelligence have been proposed since before the twentieth century, with no consensus reached by scholars. Within the discipline of psychology, various approaches to human intelligence have been adopted. The psychometric approach is especially familiar to the general public, as well as being the most researched and by far the most widely used in practical settings.[1] History of the term Intelligence derives from the Latin verb intelligere which derives from inter-legere meaning to "pick out" or discern. -

Prace Komisji Historii Nauki PAU XIV 2015 / Proceedings of the PAU Commission on the History of Science XIV 2015

PRACE KOMISJI HISTORII NAUKI PAU TOM XIV Komitet Redakcyjny / The Editorial Committee Redaktor naczelny i sekretarz redakcji / Editor-in-Chief and Editorial Secretary: prof. dr hab. Michał KOKOWSKI (Instytut Historii Nauki im. L. i A. Birkenmajerów PAN; Warszawa–Kraków) Zastępca redaktora naczelnego / Deputy Editor-in-Chief: prof. dr hab. Jerzy KREINER (em. prof., Instytut Fizyki Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego; Kraków) Redaktor statystyczny / Statistical Editor: dr Alicja RAFALSKA-ŁASOCHA (Zakład Chemii Nieorganicznej, Wydział Chemii, Uniwersytet Jagielloński; Kraków) Redaktorzy pomocniczy / Advisory Editors: prof. Jan GOLINSKI, PhD (University of New Hampshire, College of Liberal Arts, Department of History; Durham, Great Britain) dr Jan SURMAN (Leibniz Graduate School „Geschichte, Wissen, Medien in Ostmittel europa”, HerderInstitut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung; Marburg, Germany) dr hab. Piotr DASZKIEWICZ (Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle; Paris, France) Redaktor językowy (jęz. polski) / Linguistic Editor (Polish): Edyta PODOLSKA-FREJ (Dział Wydawnictw Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności / Publishing Department of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences; Kraków) Redaktor językowy (jęz. angielski) / Linguistic Editor (English): Filip KLEPACKI Od kolejnego numeru PRACE KOMISJI HISTORII NAUKI PAU będą się ukazywać pod nowym tytułem STUDIA HISTORIAE SCIENTIARUM. Zostanie zachowana ciągłość wydawnicza i tematyczna; numeracja tomów będzie zapisywana liczbami arabskimi a nie rzymskimi (jest to podyktowane kwestiami tech nicznymi). -

Positivism in Poland Was Synthesized Into a National Reawakening Through the Literary Works of Boleslaw Prus During the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century

Nolan Kinney The Positive Reawakening Of Polish Nationalism Positivism is an intellectual movement that emerged in Europe during the mid to late 19th century. This movement was a direct reaction to Romanticism and impacted what had been the country of Poland in a very unique way. Poland was partitioned by Prussia, Russia, and Austria, and by 1795 the nation that once was Poland no longer existed on the map. Positivism was a philosophy developed by Auguste Comte a Frenchman in 1856. This philosophy was adapted by Polish intellectuals, writers, poets, and politicians in hopes of using this to re-establish Poland’s national and cultural identity without the existence of the Polish nation. Positivism in Poland was synthesized into a national reawakening through the literary works of Boleslaw Prus during the second half of the nineteenth century. Prus was a journalist that turned to writing fiction describing Polish society under the influence of Positivism. He wrote a series of books that show in detail the influence of positivist thought on the different facets of society. Prus represents Polish society in the majority of works and he also includes positivist commentary and represents the conflict between Positivist thought and the Polish reality. Those books were titled, The Outpost(1886), The Doll(1889), and The Pharaoh(1895). This paper is going to examine The Doll, and The Outpost, and how Positivism impacted Polish society. Positivism was a path to promoting Polish nationalism between 1860 and 1890. In the Polish case it separated the nation from that of the people. In Poland, Positivism was based on Comte’s philosophy that all parts of society are working toward one goal. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. To Catch a Wave: The Beach Boys and Rock Historiography Luis A. Sánchez PhD Music Research The University of Edinburgh 2011 i Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis, submitted in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh, and the research contained herein is of my own composition, except where explicitly stated in the text, and was not previously submitted for any other degree or professional qualification at this or any other university. __________________________________ Luis A. Sánchez, 16 June, 2011 ii Abstract From the release of their first single “Surfin’” in 1961 to the release of the album Pet Sounds in 1966, rock history traces the arc of the American rock group the Beach Boys in broad terms of the early-sixties Southern California surf music trend and the revolutionary effects of the Beatles’ stateside arrival in 1964.