Umar Farooq Zain (4)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad Ehsaas Undergraduate Scholarship Project (List of Recommended & Waiting Applicants)

National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad Ehsaas Undergraduate Scholarship Project (List of Recommended & Waiting Applicants) Semester CUURENT_EDUC S.NO. Name of the candidate Father Name Class/Program Decision (Fall 2019) ATION_CAMPUS 1 Saddam Hussain Ghulam Rasool BS English 2nd Recommended Main Campus 2 Zeeshan Zarin Usman Zarin BS Economics 2nd Recommended Main Campus 3 Sana Iftikhar Iftikhar Ahmed BS MASS COM 5th Recommended Main Campus 4 Mudasir Iqbal Nigah Wali BS Pak Study 2nd Recommended Main Campus 5 Amina Andaleeb Muhammad Ibrahim BS T & I 2nd Recommended Main Campus 6 Aqsa Tariq Tariq Hussain Nazar BS Psychology 4th Recommended Main Campus 7 Rabia Mukhtar Mukhtar Ahmad BS English 1st Recommended Multan Campus 8 Muhammad Nasir Aziz Abdul Wadood Aziz BSSE 3rd Recommended Main Campus 9 Mohammad Ahmad Bashir Ahmad BS PAG 1st Recommended Main Campus 10 Mohammad Asghar Muhammad Mithal BS English 4th Recommended Main Campus 11 Fida Ahmed Khair Muhammad BS IR 4th Recommended Main Campus 12 Sarwar Ghulam Ghulam Muhammad BS GPP 2nd Recommended Main Campus 13 Kainat Sheikh Sheikh Muhammad Ijaz BS English 3rd Recommended Lahore Campus 14 Ijaz Ahmad Nazar Khan BS English 2nd Recommended Peshawar Campus 15 Rooh Ullah Shah Mardan BS IR 3rd Recommended Main Campus 16 Shiza Waheed Abdul Waheed BS English 3rd Recommended Main Campus 17 Kiran . Didar Ali BS English 1st Recommended Main Campus 18 Sonia Abbas Ghulam Abbass BS Psychology 1st Recommended Main Campus 19 Sakhawat Ali Ibrahim BS PAG 3rd Recommended Main Campus 20 Naveed Ali -

Conflict in Afghanistan I

Conflict in Afghanistan I 92 Number 880 December 2010 Volume Volume 92 Number 880 December 2010 Volume 92 Number 880 December 2010 Part 1: Socio-political and humanitarian environment Interview with Dr Sima Samar Chairperson of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission Afghanistan: an historical and geographical appraisal William Maley Dynamic interplay between religion and armed conflict in Afghanistan Ken Guest Transnational Islamic networks Imtiaz Gul Impunity and insurgency: a deadly combination in Afghanistan Norah Niland The right to counsel as a safeguard of justice in Afghanistan: the contribution of the International Legal Foundation Jennifer Smith, Natalie Rea, and Shabir Ahmad Kamawal State-building in Afghanistan: a case showing the limits? Lucy Morgan Edwards The future of Afghanistan: an Afghan responsibility Conflict I in Afghanistan Taiba Rahim Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action www.icrc.org/eng/review Conflict in Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal web site at: ISSN 1816-3831 http://www.journals.cambridge.org/irc Afghanistan I Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief: Vincent Bernard The Review is printed in English and is Editorial assistant: Michael Siegrist published four times a year, in March, Publication assistant: June, September and December. Claire Franc Abbas Annual selections of articles are also International Review of the Red Cross published on a regional level in Arabic, Aim and scope 19, Avenue de la Paix Chinese, French, Russian and Spanish. The International Review of the Red Cross is a periodical CH - 1202 Geneva, Switzerland published by the ICRC. Its aim is to promote reflection on t +41 22 734 60 01 Published in association with humanitarian law, policy and action in armed conflict and f +41 22 733 20 57 Cambridge University Press. -

Katalog Der Nah-, Mittelöstlichen Und Islamischen Präsenz Im Internet Vorbemerkung

Katalog der nah-, mittelöstlichen und islamischen Präsenz im Internet Vorbemerkung Dieser Katalog erhebt keinen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit. Internetressourcen, die nicht mehr zugänglich sind, werden weiter aufgeführt und mit einem entsprechenden Hinweis versehen. Bestehende Links können z.Z. nicht überprüft werden. Es sei auf Internetarchive wie http://www.archive.org verwiesen, die periodisch Teile des Internet speichern. Nicht mehr zugängliche Ressourcen können auch durch die Suche nach Dokumenttiteln wieder aufgefunden werden. Ergänzungen und Korrekturen sind zuletzt im Juni 2010 vorgenommen worden. Selbstverständlich beinhaltet das Aufführen von Links keine Identifikation des Verfassers mit den Inhalten der einzelnen Internetressourcen. Themen Einstiegspunkte Afrika - südlich der Sahara Ahmadiya Aleviten Antikritik Arabische Staaten - Ägypten Arabische Staaten - Algerien Arabische Staaten - Bahrain Arabische Staaten - Irak Arabische Staaten - Jemen Arabische Staaten - Libanon Arabische Staaten - Libyen Arabische Staaten - Marokko Arabische Staaten - Mauretanien Arabische Staaten - Palästina Arabische Staaten - Saudi-Arabien Arabische Staaten - Sudan Arabische Staaten - Syrien Arabische Staaten - Tunesien Arabische Staaten - Verschiedene Asien - Afghanistan Asien – Bangla Desh Asien - Indien Asien - Indonesien Asien - Iran Asien - Kashmir Asien - Malaysia Asien - Pakistan Asien/Europa - Türkei Asien - Verschiedene Australien/Neuseeland Baha'i Christentum - Islam Christliche Missionsbestrebungen Drusen Europa - Verschiedene Staaten -

IN THIS ISSUE: Briefs

VOLUME IX, ISSUE 8 u FEBRUARY 24, 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: BRIEFS..................................................................................................................................1 GOVERNMENT OFFENSIVE TRIGGERS TALIBAN REPRISAL ATTACKS IN PAKISTan’s mohmand aGENCY By Animesh Roul......................................................................................................3 AFTER MUBARAK: EGypt’s islamisTS RESPOND TO A SECULAR REVOLUTION Malik Mumtaz By Hani Nasira............................................................................................................5 Qadri SUFI MILITANTS STRUGGLE WITH DEOBANDI JIHADISTS IN PAKISTAN By Arif Jamal............................................................................................................6 Terrorism Monitor is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation. The Terrorism Monitor is designed to be read by policy- makers and other specialists HAVE DARFUR REBELS JOINED QADDAFI’S MERCENARY DEFENDERS? yet be accessible to the general public. The opinions expressed A handful of unconfirmed reports from Libya have cited the presence of Darfur within are solely those of the rebels in the ranks of the African mercenaries defending the regime of President authors and do not necessarily Mu’ammar Qaddafi al-Intibaha( [Khartoum], February 21; Reuters, February reflect those of The Jamestown Foundation. 22). A spokesman for the Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs told a press gathering that authorities were investigating the claims (Sudan Tribune, February 22). Darfur -

January to March 2021

Welcome Back to School Note: Don’t print out this newsletter at all, because it has pictures and printing out the pictures of living things is impermissible by Islamic Shariah. Note: Don’t print out this newsletter at all, because it has pictures and printing out the pictures of living things is impermissible by Islamic Shariah. Note: Don’t print out this newsletter at all, because it has pictures and printing out the pictures of living things is impermissible by Islamic Shariah. Obligation of Fasting ﻳٰٓ ﹷﺎ ﻳ ﹷهﺎ �اﻟ ﹻﺬﻳْ ﹷﻦ ﹷ�ﻣﻨﹹ ْﻮا ﹹﻛﺘﹻ ﹷﺐ ﹷﻋ ْﻠﹷﻴﻜﹹ ﹹﻢ اﻟﺼ ﹷﻴ ﹹﺎم ﹷﻛ ﹷﻤﺎ ﹹﻛﺘﹻ ﹷﺐ ﹷﻋ�ﹷ� �اﻟ ﹻﺬﻳْ ﹷﻦ ﹻﻣ ْﻦ ﹷﻗ ْﺒﻠﹻﻜﹹ ْﻢ ﹷﻟ ﹷﻌ �ﻠﻜﹹ ْﻢ ﹷﺗ �ﺘ ﹹﻘ ْﻮ ﹷن (Verse 183, Surah Al-Baqarah, Part 2) Translation from Kanzul Iman: O believers! Fasting has been made obligatory upon you, like it was made obligatory upon those before you, that you may attain piety. Fasting and children When the children are capable of fasting, ask them to observe fast. When the children fast for the first time, encourage them. Prepare such an eective schedule for your fasting children that it includes time for worship, rest and other activities as well. However, keep them away from playing a lot like a normal day, else it will be quite dicult for them to keep patient until Iftar. The children who are not observing fast due to their lower age, ask them to avoid eating in public to respect Ramadan. Tell your children the excellence of Ramadan and explain the rulings of fasting in an easy way keeping their age in mind. -

Transnational Islamic Networks

Volume 92 Number 880 December 2010 Transnational Islamic networks Imtiaz Gul Imtiaz Gul is the Executive Director of the Centre for Research and Security Studies,Islamabad, and has been covering security and terrorism-related issues in the South/Central Asian region for more than two decades. Abstract Besides a surge in terrorist activities, events following the 11 September terrorist attack on the United States have raised a new challenge for the world: the emergence of transnational Islamic networks, predominantly influenced by organizations such as Ikhwan al Muslimeen (the Muslim Brotherhood) and Al Qaeda, which are helping to spread a particular religious ideology across the globe and are also having an impact on pre-existing groups in Afghanistan and Pakistan. This article gives an overview of the role of Islamist networks and their influence, drawn from Al Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood, in South and South-west Asia and the Afghanistan– Pakistan region in particular. It also explains how local like-minded outfits have used Al Qaeda’s anti-Western jargon to recruit foot soldiers and enlist support within their society, besides serving as financial conduits for the radical Wahabite/Salafi reformists. Traditional Islam in South and South-west Asia Islam came to the Indian subcontinent in the eighth century with the Arab con- quest of Sindh (now the fourth province of Pakistan in the south). In the ensuing decades, however, besides struggles and battles for political domination among kings and sultans of the region, Sufis and saints played a major role in influencing traditional Islam in South (and West) Asia. -

Maulana Shah Ahmed Noorani Siddiqui: A

MAULANA SHAH AHMED NOORANI SIDDIQUI: A POLITICAL STUDY ZAHID AHMED DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD SPRING 2015 MAULANA SHAH AHMED NOORANI SIDDIQUI: A POLITICAL STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ZAHID AHMED ISLAMABAD, PAKISTAN SPRING 2015 To My Parents and Wife ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost I offer my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Razia Sultana, who has supported me though out my thesis with her patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and knowledge whilst allowing me the room to work in my own way. Her guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis. Her insightful comments, hard questions and constructive criticisms at different stages of my research were thought-provoking and they helped me focus my ideas. My sincere thanks to Maulana Younas Noshahi, Maulana Jameel Ahmed Naeemi, Late Maulana Ishaq Naziri, Zaid Sarwar, Hassan Nawaz and Dr.Arshad Bashir Mirza for helping me in material collection and giving free access to their personal collections. I am thankful to all my teachers particularly Prof. Dr. Sikandar Hayat, Prof. Dr. Aslam Syed, and Prof. Masood Akther, for their help and guidance. I especially thank Shah Muhmmad Anas Noorani, Shah Muhmmad Owais Noorani, Azhar Iqbal, Khalil Ahmed Rana, Noor Alam Shah, Shabbir Chishti, Mahboobur Rasool for helping me in identification of resources. I am grateful to the staff of National Archives of Pakistan, National Library of Pakistan, National Institute of Pakistan Studies, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Institute of Policy Studies, Heavy Industry Taxila Education City Religious Education Library, Dr. -

The Clash of Civilizations the Muhammad Caricatures As a Case Study

The Clash of Civilizations The Muhammad Caricatures as a Case Study Dr. Eitan Azani, Dr. Ely Karmon, Dr. Michael Barak, Mrs. Lorena Atiyas-Lvovsky November 2020 1 The Clash of Civilizations The Muhammad Caricatures as a Case Study Europe is experiencing a wave of terror attacks in response to the publication of Muhammad caricatures. These attacks are a manifestation of a clash between two civilizations - one is the western liberalism and the other is radical Islamism that global jihadi organizations and the supporters of radical ideologies follow. These attacks in major European cities despite being tactical in nature, have a strategic effect on the population, decision makers and the relationship in the international arena between the West and Muslim countries and global jihadi organizations. From the analysis of the attacks and the reactions to them, as presented in the article: the main concern in light of the success of recent weeks’ attacks and the call for additional ones by terrorist organizations, is that we may be facing the beginning of a new wave of violence. In this context there is a possibility that attacks will spill over from France into the close European circle or even farther. The global nature of the threat is made possible, inter alia, due to amongs othersn, the threat posed by foreign fighters returning from jihadi theaters back to Europe and releasing those who have been convicted for terrorism. The French response to the attacks stressed the importance of secularism, freedom of worship and freedom of speech in the Republic. France has elevated its level of readiness to the highest one and French President Macron announced a far-reaching program to contend with radical Islam. -

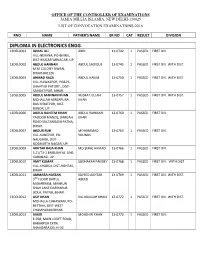

University Polytechnic

OFFICE OF THE CONTROLLER OF EXAMINATIONS JAMIA MILLIA ISLAMIA, NEW DELHI-110025 LIST OF CONVOCATION EXAMINATIONS-2016 RNO NAME FATHER'S NAME ER NO CAT RESULT DIVISION DIPLOMA IN ELECTRONICS ENGG. 13DEL0001 AJMAL ALI ABID 13-0742 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. VILL-NERANA, PO-BHIKKI, DIST-MUZAFFARNAGAR, UP. 13DEL0002 ABDUL HANNAN ABDUL SADIQUE 13-0745 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. WITH DIST. M.M COLONY SIWAN, BIHAR-841226 13DEL0003 AHMAD RAZA ABDUL HAKIM 13-0750 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. WITH DIST. VILL-HAWASPOR, PO&PS- SHAHPUR PATORY , DIST- SAMASTIPUR, BIHAR. 13DEL0005 ABDUL MANNAN KHAN NUSRAT ULLAH 13-0757 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. WITH DIST. MOHALLAH MIRZAPURA KHAN BASI KIRATPUR, DIST- BIJNOR, UP. 13DEL0006 ABDUL RAHEEM KHAN ABDUL RAHMAN 13-0760 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. YAQOOB MANZIL, DARGAH KHAN ROAD SULTANGANJ PATNA, BIHAR. 13DEL0007 ABDUR RUB MOHAMMAD 13-0763 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. VILL-SONEPUR, PO- YOUNUS NAUGARH, DIST- SIDDHARTH NAGAR, UP. 13DEL0009 AKHTAR RAJA KHAN MO.SERAJ AHMAD 13-0766 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. S 21/73-1 ENGLISHIYA LINE, VARANASI, UP. 13DEL0010 AMIT KUMAR SUDHAKAR PANDEY 13-0768 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. WITH DIST. VILL-KHAROJ, DIST-ROHTAS, BIHAR 13DEL0011 AMMARA HASSAN SAYEED AKHTAR 13-0769 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. WITH DIST. 3RD FLOOR BAITUL ABEED MUKARRAM, MAHRUN SHAH LANE DARIYAPUR GOLA, PATNA, BIHAR. 13DEL0012 ASIF KHAN KALIMULLAH KHAN 13-0772 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. WITH DIST. MOHALLA-CHHAWANI, PO- BETTIAH, DIST-WEST CHAMPARAN BIHAR. 13DEL0013 BAKIR MOHSHIN KHAN 13-0773 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. E-928, MAIN LOOFT ROAD, BABARPUR EXTN, SHAHDARA DELHI-32 OFFICE OF THE CONTROLLER OF EXAMINATIONS JAMIA MILLIA ISLAMIA, NEW DELHI-110025 LIST OF CONVOCATION EXAMINATIONS-2016 RNO NAME FATHER'S NAME ER NO CAT RESULT DIVISION 13DEL0014 FARAZ AHMAD MUMTAZ HUSAIN 13-0775 1 PASSED FIRST DIV. -

Profile of Sunni Tehreek by Fahad Nabeel, Muhammad Omar Afzaal and Sidra Waseem

Profile of Sunni Tehreek by Fahad Nabeel, Muhammad Omar Afzaal and Sidra Waseem Research Brief www.cscr.pk Introduction The Sunni Tehreek (ST) is a Sunni religio-organization of Pakistan. The party follows the Barelvi school of thought. The organization was formed in 1990 to prevent what the ST describes as ‘the capturing of the mosques and madrassas of the Barelvi school of thought’ by Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith groups. The concept of re-taking the mosques and madrassas defined their main motto, which was ‘Jawaniyan lutaaingai, masjidain bachayeingai [We will sacrifice our lives to protect our mosques]. It is part of the Sunni Ittehad Council, an alliance of Barelvi political parties. In 2009, the group’s leader, Muhammad Sarwat Ejaz Qadri, also formed the Pakistan Inquilab Tehreek as a political wing of the organization. In 2012, the party was converted into a political party with the name of Pakistan Sunni Tehreek (PST). History Salim Qadri, hailing from Karachi’s Saeedabad, started driving an auto rickshaw for livelihood after his matriculation examination. When Dawat-e-Islami (DeI) was established in I980, Salim Qadri became the leader of DeI’s Saeedabad wing. His enthusiastic services soon offered him a position in DeI and Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan (JUP). In 1988, he stood as JUP’s candidate for PA-75 in the Sindh Assembly, but he was defeated. After the elections, Salim Qadri quit his previous occupation and started a started a business of fabric and poultry farm. The ST was established by Salim Qadri in 1990 after he quit the DeI. -

Warrior Tanveer

Social media posts mostly from Pakistan flooded Facebook and Twitter calling him #GhaziTanveer (Warrior Tanveer). Soon after pictures of the alleged killer also started flooding Dawt-e-Islami related Facebook pages along with the picture of Mumtaz Qadri, who was hanged by Pakistan for killing former Governor Salman Taseer. Tanveer Qadri Attari Dawat-e-Islami extremists also shared Tanveer’s Facebook profile which uses the name ‘Tanveer Attari Qadri al Husaini‘ in Urdu and is filled with facebook posts praising killer Mumtaz Qadri and Dawat-e-Islami. The practice of adding Attari and Qadri to one’s name is common among Dawat-e-Islami members. Taveer’s Facebook posts from March 24th, the day of the killing are all in praise of different individuals who killed blasphemers. His last post is in praise of Mumtaz Qadri. The only TV channel he has liked on his Facebook profile is Madani Channel, which is run by Dawat-e-Islami from the town of Rochdale, UK. The same town made headlines in 2012 after child sex grooming activities of a Pakistani gang came to light. Dawat-e-Islami founder Ilyas Qadri Attari Dawat-e-Islami’s website describes Ahmadis as Kafir (Infidel) and Murtad (Apostates) and even goes to say that those who disagree are also Kafir (Infidels). The website further says: Anyone who believes in a Prophet after Muhammad, It doesn’t matter if they are Ahmadi or not are Murtad (Apostates) and they will be subject to the conditions of Murtads (Apostates). Source As to the what conditions the Apostates are subject to, Dawat-e-Islami website has a whole section in Urdu language explaining why the punishment for Apostasy is Death, the website further explains a Blasphemer is also an Apostate and hence WajibulQatal (worthy of death). -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan: a Literature Review List of Tables Table 3.1

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert D. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration.