Political Memory in and After the Persian Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

The Second After the King and Achaemenid Bactria on Classical Sources

The Second after the King and Achaemenid Bactria on Classical Sources MANEL GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ Universidad de Barcelona–CEIPAC* ABSTRACT The government of the Achaemenid Satrapy of Bactria is frequently associated in Classical sources with the Second after the King. Although this relationship did not happen in all the cases of succession to the Achaemenid throne, there is no doubt that the Bactrian government considered it valuable and important both for the stability of the Empire and as a reward for the loser in the succession struggle to the Achaemenid throne. KEYWORDS Achaemenid succession – Achaemenid Bactria – Achaemenid Kingship Crown Princes – porphyrogenesis Beyond the tradition that made of Zoroaster the and harem royal intrigues among the successors King of the Bactrians, Rege Bactrianorum, qui to the throne in the Achaemenid Empire primus dicitur artes magicas invenisse (Justinus (Shahbazi 1993; García Sánchez 2005; 2009, 1.1.9), Classical sources sometimes relate the 155–175). It is in this context where we might Satrapy of Bactria –the Persian Satrapy included find some explicit references to the reward for Sogdiana as well (Briant 1984, 71; Briant 1996, the prince who lost the succession dispute: the 403 s.)– along with the princes of the offer of the government of Bactria as a Achaemenid royal family and especially with compensation for the damage done after not the ruled out prince in the succession, the having been chosen as a successor of the Great second in line to the throne, sometimes King (Sancisi–Weerdenburg 1980, 122–139; appointed in the sources as “the second after the Briant 1984, 69–80). -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

Christianity in Afghanistan By: Brittany Tierney

Christianity in Afghanistan By: Brittany Tierney Christianity is usually known throughout history for its expansion, “from the Middle East to Europe and ultimately onto the global stage…we rarely think of major reverses or setbacks.” 1 However, this is not the case of Christianity in central Asia, and most notably in Afghanistan, where Christianity has altogether been annihilated from the country. Afghanistan, now referred to after its 2004 constitution as the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, has a history full of violence and territorial conquests, most recognizably between the Arabs and Mongols. While the country today is over 99% Islam,2 it was once home to an array of religious groups including Hinduism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity. Even after the initial Islamic spread of the seventh century, Christianity and most other religions were free from persecution. Christianity and Islam co-existed for many centuries within the Afghan boarders, until the Mongol army invaded the country and began a long reign of power that included religious persecution. To better understand the eradication of Christianity in Afghanistan more clearly, this essay will focus on three main areas: the Islamic and Christian history of Afghanistan, how the two co-existed peacefully for centuries, and then hone in specifically on the Mongol empire of the thirteenth century, when Christianity was violently persecuted under the Mongol general, Ghazan. Today, everything in Afghanistan is closely tied to Islam, from its politics to social customs, but Afghanistan looked much different throughout its history. The sparsely populated landscape of ancient Afghanistan made it “ripe for conquest but difficult to rule: empires rose and fell periodically throughout its history.” 3 Before the Islamic conquests occurred in the seventh century, Afghanistan, situated in central Asia, was dominated by the 1 Phillip Jenkins, The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia- and How it Died (New York: Harper Collins, 2008), 2. -

Skeleton from Greek Mystery Tomb to Be Identified Next Month 19 January 2015

Skeleton from Greek mystery tomb to be identified next month 19 January 2015 speculation that a member of Alexander the Great's entourage had been buried there. The ministry had originally thought that a single skeleton lay in the tomb, but on Monday said that out of 550 bone fragments found, 157 had been matched to specific bodies so far. Other bones were those of animals, including a horse. The tomb, measuring 500 metres (1,640 feet) in circumference and dug into a 30-metre hill—was found to contain sculptures of sphinxes and caryatids, intricate mosaics and coins featuring the The site where archaeologists have unearthed a funeral face of Alexander the Great. mound dating from the time of Alexander the Great in Amphipolis, northern Greece pictured on November 22, 2014 Bones from at least five people, including a baby and an elderly woman, were identified in a massive tomb in Greece dating back to the era of Alexander the Great, the culture ministry said Monday. "A minimum number of five people have been identified from bone remains, four of whom were buried and one of whom was burned," the ministry said in a statement. "The dead are a woman, two middle-aged men and a newborn" and a fifth person whose sex could not be verified, it said. The woman was estimated to be aged over 60, and the two men between 35 and 45 years old, officials said. No other details were immediately available on the baby and the fifth person. The excavation of the tomb in Amphipolis, northern Greece—the largest ever unearthed in the country—made global headlines this summer amid 1 / 2 Picture provided by the Greek Ministry of Culture on November 12, 2014 shows a grave found in the tomb dating to the Alexander the Great era (356-323 BC) at the ancient Amphipolis archaeological site in the northern region of Macedonia Before the announcements, it was thought that the tomb could contain Alexander's Bactrian wife Roxana, the king's mother Olympias, or one of his generals. -

The Death of Alexander the Great 1. Introduction

The death of Alexander the Great THE DEATH OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT ABSTRACT The circumstances of Alexander’s death are reviewed. Since contemporary sources vary in their accounts of the reason for his death, they are briefly reviewed and assessed. The account of Alexander’s final illness is then discussed as recorded in the King’s Journal and the Liber de morte testamentumque Alexandri Magni. The theory that he was poisoned is rejected, as is the hypothesis that he drank himself to death. His final illness shows symptoms characteristic of malignant tertian malaria (Plasmodium fal- ciparum), possibly precipitated by recent wounds, exhaustion and heavy drinking. 1. INTRODUCTION Alexander, King of Macedonia, conqueror of the Persian empire, died in Babylon at sunset on the 10th of June, 323 BC.1 He was not yet 33 years old, had been king for 12 years and 8 months and had shown himself to be fully deserving of the title “The Great”. Educated by Aristotle, trained in warfare by his father Philip II, he invaded Asia at the age of 22 and defeated Darius III within 3 years. He never returned to Macedonia but commenced with the establishment of an Asian em- pire based on Hellenistic culture whilst incorporating the best elements of the Persians and other conquered nations. With few exceptions he was remarkably magnanimous towards his former enemies, perform- ing acts of justice far in advance of his time. As Tarn (1948:I.124- 125) puts it: This was probably the most important thing about him: he was a great dreamer. To be mystical and intensely practical, to dream greatly and to do greatly, is not given to many men; it is this combination which gives Alexander his place apart in history. -

Political Memory in and After the Persian Empire Persian the After and Memory in Political

POLITICAL IN MEMORY AND AFTER THE PERSIAN EMPIRE At its height, the Persian Empire stretched from India to Libya, uniting the entire Near East under the rule of a single Great King for the rst time in history. Many groups in the area had long-lived traditions of indigenous kingship, but these were either abolished or adapted to t the new frame of universal Persian rule. is book explores the ways in which people from Rome, Egypt, Babylonia, Israel, and Iran interacted with kingship in the Persian Empire and how they remembered and reshaped their own indigenous traditions in response to these experiences. e contributors are Björn Anderson, Seth A. Bledsoe, Henry P. Colburn, Geert POLITICAL MEMORY De Breucker, Benedikt Eckhardt, Kiyan Foroutan, Lisbeth S. Fried, Olaf E. Kaper, Alesandr V. Makhlaiuk, Christine Mitchell, John P. Nielsen, Eduard Rung, Jason M. Silverman, Květa Smoláriková, R. J. van der Spek, Caroline Waerzeggers, IN AND AFTER THE Melanie Wasmuth, and Ian Douglas Wilson. JASON M. SILVERMAN is a postdoctoral researcher in the Faculty of eology PERSIAN EMPIRE at the University of Helsinki. He is the author of Persepolis and Jerusalem: Iranian In uence on the Apocalyptic Hermeneutic (T&T Clark) and the editor of Opening Heaven’s Floodgates: e Genesis Flood Narrative, Its Context and Reception (Gorgias). CAROLINE WAERZEGGERS is Associate Professor of Assyriology at Leiden University. She is the author of Marduk-rēmanni: Local Networks and Imperial Politics in Achaemenid Babylonia (Peeters) and e Ezida Temple of Borsippa: Priesthood, Cult, Archives (Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten). Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Edited by Waerzeggers Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-089-4) available at Silverman Jason M. -

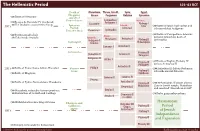

Hellenistic Period and World

The Hellenistic Period 323–63 BCE Death of Macedonia, Thrace, Asia M., Syria, Egypt, 323 Diogenes; Greece Pergamon Babylon Cyrenaica Death of Alexander suicide of Lysimachus / Ptolemies... 310 Demosthenes Roxana & Alexander IV murdered; Cassander Antigonus I Ptolemy I 306 e Diadochi assume title of kings Epicurus; Seleucids... Soter 301 300 Seleucus I Battle of Ipsus: Lysimachus and Euclid; Lysimachus Seleucus defeat Antigonus Zeno the Stoic Demetrius I 280 281 Pyrrhus invades Italy Attalids... Battle of Corupedium: Seleucus 278 Celts invade Anatolia Antigonids... Philetaerus Antiochus I defeats Lysimachus; death of Antigonus II Ptolemy II Lysimachus Septuagint Gonatas Philadelphus Eumenes I Antiochus II Archimedes Ptolemy III Demetrius II Seleucus II Euregetes Antigonus III Attalus I Ptolemy IV 217 Battle of Raphia: Ptolemy IV Philopater defeats Antiochus III Antiochus III 202 Philip V 200 Battle of Zama: Rome defeats Hannibal Rosetta 200 Antiochus III defeats Ptolemies; Stone Ptolemy V Seleucids control Palestine 189 Battle of Magnesia Epiphanes Eumenes II Seleucus IV Perseus 168 Antiochus IV Battle of Pydna: Rome defeats Macedonia Ptolemy VI 168, 167 Antiochus IV places altar to Demetrius I Philometer Zeus in Jewish temple; Mattathias and sons lead “Maccabean Revolt” 148 Macedonia reduced to Roman province; Attalus II 146 Destruction of Corinth and Carthage Demetrius II 142 Judea gains independence Attalus III vs. others 120 Mithridates becomes king of Pontus Pharisees and Antiochus VIII Hasmonean Sadducees Grypos; Ptolemy IX Period appear Antiochus IX 100 Ptolemy X of Jewish Independence Ptolemy IX and Expansion Ptolemy XII 66 Pompey commands th e Roman East 5130000-hellenistic-period-tml-map-bcrx BcResources.net © ncBc The Hellenistic World 323–63 BCE 189 Battle 168 Battle of of Magnesia CELTS Pydna Jaxartes R. -

Alexander the Great's Cabinet

Letter from Academic Assistant I would like to start by welcoming you all to this annual session of HaydarpaşaMUN! I also would like to state that I think you are the twelve luckiest delegates of the conference since you are now allocated in our traditional World-Changing Commander’s Cabinet themed committee. In this year’s cabinet you will represent the bravest and the most sharp witted of the soldiers since you will be serving Alexander III of the Macedons as known as Alexander the Great and shall have the most adventurous battles devoted to his army. On the other hand you will further learn upon the history’s biggest mastermind and be granted the chance to rewrite it. I can guarantee you that you will have the most of fun and also the biggest academic pleasure. Therefore I would like to thank every person behind this conference by starting with our passionate and sympathetic Secretary General Zeynep Naz Coşkun and our esteemed and hardworking Crisis Team since they are the ones who will be providing you this highly prestigious committee before concluding my thanks I would also like to thank my academic trainee Zeynep Erşen for her hardworks and fellow companionship In order to conclude I can recommend you nothing but further research the topic since ancient warfare ,political structure and relations can be really hard to understand. I personally recommend the website called ancient history encyclopedia also the videos that briefly explains warfare of the era since visual explanations are more easy to understand. In case you have any questions please don’t hesitate to contact me and my trainee via m [email protected] and z[email protected] Hope to see you soon! Yağmur Zühal Tokur - Academic Assistant Zeynep Erşen - Academic Trainee Introduction Alexander the Great whom you will become companies of for these four days was not just the king of Macedonia or the leader that started Hellenistic Era. -

Progress and Development of the Tolerance Principle in Central Asia (Ancient and Early Middle Ages)

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 04, APRIL 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Progress And Development Of The Tolerance Principle In Central Asia (Ancient And Early Middle Ages) Murtazaeva Rakhbar, Adilov Abror, Saipova Kamola, Atadjanova Sayora Abstract: In this article, the authors highlighted the historical aspects of the formation and development of the principles of tolerance in the socio- political and spiritual life in antiquity and the early Middle Ages among the peoples of Central Asia. The historical aspects of this problem have not yet been published in international publications. Index Terms: Central Asia, tolerance, the ancient period, the early Middle Ages, territory, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, Buddhism. ———————————————————— 1. INTRODUCTION the Conference rightly recognized the experience of At the end of the 20th century, lots of changes in the socio- Uzbekistan in tolerance. political and economic sphere of the world accelerated the process of globalisation. As a result, instead of struggle 2. METHODS between ‗cold war‘, ideologies and systems; terrorism, The role of tolerance in the socio-political and spiritual extremism, drug addiction, decreasing social and moral event which took place in Central Asia from the ancient values, the institution of the family, and ‗culture‘ called times to the 16th century A.D. has been shown. The ‗common‘ have begun to enter the lives of the young. At the problem of history of ancient and medieval tolerance in same time, the rise of racial, religious, territorial, ethnic Central Asia have been researched by Uzbek scholars such conflicts in the world, the growing of the population, and F. Buryakov (Buryakov 2011), A. -

Alexander the Great and the “Clash” of Ancient Civilizations

International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. XXIV No 2 2018 ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND THE “CLASH” OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS Mădălina STRECHIE University of Craiova, Craiova, Romania [email protected] Abstract: Alexander the Great was not only a great political leader, but also an amazing general. He did not face only armies, but entire civilizations which he forced to merge, following his own example. We believe that his most lasting victory was the Hellenistic civilization, a new civilization that emerged after the “clash of civilizations” that Alexander, the great leader, had opposed, namely the Greek civilization versus the Persian civilization. His war was totally new, revolutionary, both in terms of fighting tactics, weapons, and especially goals. Alexander became the Great because of his ambition to conquer the world from one end to the other. Beginning with the pretext meant to take revenge for the Persian Wars, his expedition to the Persian Empire was in fact a special “clash of civilizations”. With Alexander, the West fully demonstrates its expansionist tendencies, conquering at first an empire and civilization after civilization. Thus, in turn, the Greek crusher of the new half-god of war defeated the Phoenician, Egyptian, Persian civilizations (the coordinator of the empire that initiated for the first time the process of assimilation of the defeated ones, namely Persanization).From the military point of view, Alexander the Great was the initiator of the lightning war, of course mutatis mutandis, forming a military monarchy within the conquered civilizations, turning for the first time in history, generals into important politicians, we think here of the Diadochi. -

Political Memory in and After the Persian Empire Persian the After and Memory in Political

POLITICAL IN MEMORY AND AFTER THE PERSIAN EMPIRE At its height, the Persian Empire stretched from India to Libya, uniting the entire Near East under the rule of a single Great King for the rst time in history. Many groups in the area had long-lived traditions of indigenous kingship, but these were either abolished or adapted to t the new frame of universal Persian rule. is book explores the ways in which people from Rome, Egypt, Babylonia, Israel, and Iran interacted with kingship in the Persian Empire and how they remembered and reshaped their own indigenous traditions in response to these experiences. e contributors are Björn Anderson, Seth A. Bledsoe, Henry P. Colburn, Geert POLITICAL MEMORY De Breucker, Benedikt Eckhardt, Kiyan Foroutan, Lisbeth S. Fried, Olaf E. Kaper, Alesandr V. Makhlaiuk, Christine Mitchell, John P. Nielsen, Eduard Rung, Jason M. Silverman, Květa Smoláriková, R. J. van der Spek, Caroline Waerzeggers, IN AND AFTER THE Melanie Wasmuth, and Ian Douglas Wilson. JASON M. SILVERMAN is a postdoctoral researcher in the Faculty of eology PERSIAN EMPIRE at the University of Helsinki. He is the author of Persepolis and Jerusalem: Iranian In uence on the Apocalyptic Hermeneutic (T&T Clark) and the editor of Opening Heaven’s Floodgates: e Genesis Flood Narrative, Its Context and Reception (Gorgias). CAROLINE WAERZEGGERS is Associate Professor of Assyriology at Leiden University. She is the author of Marduk-rēmanni: Local Networks and Imperial Politics in Achaemenid Babylonia (Peeters) and e Ezida Temple of Borsippa: Priesthood, Cult, Archives (Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten). Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Edited by Waerzeggers Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-089-4) available at Silverman Jason M.