(Or Do You Want the Truth)? Intersections of Punk and Queer in the 1970S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenes and Subcultures

ISSN 1751-8229 IJŽS Volume Three, Number One Realizing the Scene; Punk and Meaning’s Demise R. Pope - Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada. Joplin and Hendrix set the intensive norm for rock shows, fed the rock audience’s need for the emotional charge that confirmed they’d been at a “real” event… The ramifications were immediate. Singer-songwriters’ confessional mode, the appeal of their supposed “transparency”, introduced a kind of moralism into rock – faking an emotion (which in postpunk ideology is the whole point and joy of pop performance) became an aesthetic crime; musicians were judged for their openness, their honesty, their sensitivity, were judged, that is, as real, knowable people (think of that pompous rock fixture, the Rolling Stone interview)’. -Simon Frith, from `Rock and the Politics of Memory’ (1984: 66-7) `I’m an icon breaker, therefore that makes me unbearable. They want you to become godlike, and if you won’t, you’re a problem. They want you to carry their ideological load for them. That’s nonsense. I always hoped I made it completely clear that I was as deeply confused as the next person. That’s why I’m doing this. In fact, more so. I wouldn’t be up there on stage night after night unless I was deeply confused, too’. -John Lydon, from Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (1994: 107) `Gotta go over the Berlin Wall I don't understand it.... I gotta go over the wall I don't understand this bit at all... Please don't be waiting for me’ -Sex Pistols lyrics to `Holidays in the Sun’ INTRODUCTION: CULTURAL STUDIES What is Lydon on about? What is punk 'about’? Within the academy, punk is generally understood through the lens of cultural studies, through which punk’s activities are cast an aura of meaningful `resistance’ to `dominant’ forces. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Cultural Representations of the Moors Murderers and Yorkshire Ripper Cases

CULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF THE MOORS MURDERERS AND YORKSHIRE RIPPER CASES by HENRIETTA PHILLIPA ANNE MALION PHILLIPS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History, and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines written, audio-visual and musical representations of real-life British serial killers Myra Hindley and Ian Brady (the ‘Moors Murderers’) and Peter Sutcliffe (the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’), from the time of their crimes to the present day, and their proliferation beyond the cases’ immediate historical-legal context. Through the theoretical construct ‘Northientalism’ I interrogate such representations’ replication and engagement of stereotypes and anxieties accruing to the figure of the white working- class ‘Northern’ subject in these cases, within a broader context of pre-existing historical trajectories and generic conventions of Northern and true crime representation. Interrogating changing perceptions of the cultural functions and meanings of murderers in late-capitalist socio-cultural history, I argue that the underlying structure of true crime is the counterbalance between the exceptional and the everyday, in service of which its second crucial structuring technique – the depiction of physical detail – operates. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Women's Sex-Toy Parties: Technology, Orgasm, and Commodification

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ McCaughey, Martha, and Christina French.(2001) “Women’s Sex-Toy Parties: Technology, Orgasm, and Commodification,” Sexuality and Culture 5:3:77-96. (ISSN: 1095-5143) The version of record is available from http://www.springer.com (September 2001) Women’s Sex-Toy Parties: Technology, Orgasm, and Commodification Martha McCaughey and Christina French ABSTRACT: This article presents participant-observation research from five female-only sex- toy parties. We situate the sale of sex toys in the context of in-home marketing to women, the explosion of a sex industry, and the emergence of lifestyle and body politics. We explore the significance of sex toys for women as marketed in female-only contexts, paying particular attention to the similarities and differences with Tupperware’s marketing of plastic that promises happiness to women. We argue that sex-toy sales follow the exact patterns of Tupperware sales but, since the artifacts sold are for the bedroom rather than the kitchen, foster an even greater sense of intimacy between the women— which has both positive and negative consequences for thinking critically about the commodification of sexuality, bodies, and lifestyles in our capitalist culture. Vibrators and other sex toys constitute the technological route to a self- reflexive body project of female orgasm. We ask to what extent such a body project, achieved primarily through an individualistic, capitalistic consumption model, can offer a critique of -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Sex and the City: Branding, Gender and the Commodification of Sex Consumption in Contemporary Retailing

Sex and the city: Branding, gender and the commodification of sex consumption in contemporary retailing Martin, A. and Crewe, L. (2016) Urban Studies Abstract This paper explores the changing spatiality of the sex retail industry in England and Wales, from highly regulated male orientated sex shops, pushed to the legislative margins of the city and social respectability, towards the emergence of unregulated female orientated ‘erotic boutiques’ located visibly in city centres. This is achieved through an exploration of the oppositional binaries of perceptions of sex shops as dark, dirty, male orientated, and ‘seedy’ and erotic boutiques as light, female orientated and stylish, showing how such discourses are embedded in the physical space, design and marketing of the stores and the products sold within them. More specifically, the paper analyses how female orientated sex stores utilise light, colour and design to create an ‘upscaling’ of sexual consumerism and reflects on what the emergence of up-scale female spaces for sexual consumption in the central city might mean in terms of theorisations of the intersectionality between agency, power, gender and class. The paper thus considers how the shifting packaging and presentation of sex-product consumption in the contemporary city alters both its acceptability and visibility. Keywords Consumption, Retailing, Sex Shop, Brands, The City, Space, Gender 1 1. Introduction One of the most interesting developments in the recent study of sexuality has been an increasing focus on its spatial dimensions. In this paper we address the spatial, social and gendered contours of sex shops. This is significant as part of a broader project to theorise both the emotional and the corporeal dimensions of the consuming body, and its classed and gendered composition. -

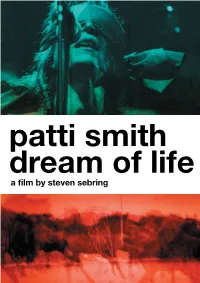

Patti DP.Indd

patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring THIRTEEN/WNET NEW YORK AND CLEAN SOCKS PRESENT PATTI SMITH AND THE BAND: LENNY KAYE OLIVER RAY TONY SHANAHAN JAY DEE DAUGHERTY AND JACKSON SMITH JESSE SMITH DIRECTORS OF TOM VERLAINE SAM SHEPARD PHILIP GLASS BENJAMIN SMOKE FLEA DIRECTOR STEVEN SEBRING PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW SCOTT VOGEL PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP HUNT EXECUTIVE CREATIVE STEVEN SEBRING EDITORS ANGELO CORRAO, A.C.E, LIN POLITO PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW CONSULTANT SHOSHANA SEBRING LINE PRODUCER SONOKO AOYAGI LEOPOLD SUPERVISING INTERNATIONAL PRODUCERS JUNKO TSUNASHIMA KRISTIN LOVEJOY DISTRIBUTION BY CELLULOID DREAMS Thirteen / WNET New York and Clean Socks present Independent Film Competition: Documentary patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring USA - 2008 - Color/B&W - 109 min - 1:66 - Dolby SRD - English www.dreamoflifethemovie.com WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY 2 rue Turgot Sundance office located at the Festival Headquarters 75009 Paris, France Marriott Sidewinder Dr. T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 Jeff Hill – cell: 917-575-8808 [email protected] E: [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com Michelle Moretta – cell: 917-749-5578 E: [email protected] synopsis Dream of Life is a plunge into the philosophy and artistry of cult rocker Patti Smith. This portrait of the legendary singer, artist and poet explores themes of spirituality, history and self expression. Known as the godmother of punk, she emerged in the 1970’s, galvanizing the music scene with her unique style of poetic rage, music and trademark swagger. -

American Punk: the Relations Between Punk Rock, Hardcore, and American Culture

American Punk: The Relations between Punk Rock, Hardcore, and American Culture Gerfried Ambrosch ABSTRACT Punk culture has its roots on both sides of the Atlantic. Despite continuous cross-fertiliza- tion, the British and the American punk traditions exhibit distinct features. There are notable aesthetic and lyrical differences, for instance. The causes for these dissimilarities stem from the different cultural, social, and economic preconditions that gave rise to punk in these places in the mid-1970s. In the U. K., punk was mainly a movement of frustrated working-class youths who occupied London’s high-rise blocks and whose families’ livelihoods were threatened by a declin- ing economy and rising unemployment. Conversely, in America, punk emerged as a middle-class phenomenon and a reaction to feelings of social and cultural alienation in the context of suburban life. Even city slickers such as the Ramones, New York’s counterpart to London’s Sex Pistols and the United States’ first ‘official’ well-known punk rock group, made reference to the mythology of suburbia (not just as a place but as a state of mind, and an ideal, as well), advancing a subver- sive critique of American culture as a whole. Engaging critically with mainstream U.S. culture, American punk’s constitutive other, punk developed an alternative sense of Americanness. Since the mid-1970s, punk has produced a plethora of bands and sub-scenes all around the world. This phenomenon began almost simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic—in London and in New York, to be precise—and has since spread to the most remote corners of the world. -

Regulations on Sex Toy Industry in Europe

Vol. 16, 2021 A new decade for social changes ISSN 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com 9 772668 779000 Technium Social Sciences Journal Vol. 16, 168-174, February, 2021 ISSN: 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com Regulations on Sex Toy Industry in Europe Yeshwant Naik Senior Researcher, Faculty of Law, University of Muenster, Germany [email protected] Abstract. The European sex toy market is witnessing a strategic sales growth. The lockdown to contain the Corona Pandemic situation is boosting the market scenario. Countries such as the UK, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain are key growing countries driving the demand for sex toys in Europe. Against this background, this article explores the sex toy industry in Europe and the few laws that govern it. It discusses that a lack of regulation of these products has allowed manufacturers to exploit the inexpensive but highly toxic materials used in the making of sex toys to the detriment of consumers, and the implications inclined towards improving the protection of consumers in Europe. Keywords. Industry, Sex Toy, Law, Europe Introduction A sex toy is an item that is mostly utilized to ease human sexual pleasure, such as vibrator or dildo. Many of these toys are made in the resemblance of human genitals. They can also be non-vibrating or vibrating. The word sex toy may, too, include sex furniture and BDSM apparatus. In European countries like Germany, Denmark, and Holland, safety regulations on the sex toy industry do not exist. This permits the manufacturers to manufacture goods without any limits of reporting the chemical or the material utilized in the product (Döring & Poeschl, 2019). -

APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH Axis.Wmg.Com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

2017 NEW RELEASE SPECIAL APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Le Soleil Est Pres de Moi (12" Single Air Splatter Vinyl)(Record Store Day PRH A 190295857370 559589 14.98 3/24/17 Exclusive) Anni-Frid Frida (Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) PRL A 190295838744 60247-P 21.98 3/24/17 Wild Season (feat. Florence Banks & Steelz Welch)(Explicit)(Vinyl Single)(Record WB S 054391960221 558713 7.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles, Bowie, David PRH A 190295869373 559537 39.98 3/24/17 '74)(3LP)(Record Store Day Exclusive) BOWPROMO (GEM Promo LP)(1LP Vinyl Bowie, David PRH A 190295875329 559540 54.98 3/24/17 Box)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Live at the Agora, 1978. (2LP)(Record Cars, The ECG A 081227940867 559102 29.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live from Los Angeles (Vinyl)(Record Clark, Brandy WB A 093624913894 558896 14.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits Acoustic (2LP Picture Cure, The ECG A 081227940812 559251 31.98 3/24/17 Disc)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits (2LP Picture Disc)(Record Cure, The ECG A 081227940805 559252 31.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Groove Is In The Heart / What Is Love? Deee-Lite ECG A 081227940980 66622 14.98 3/24/17 (Pink Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Coral Fang (Explicit)(Red Vinyl)(Record Distillers, The RRW A 081227941468 48420 21.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live At The Matrix '67 (Vinyl)(Record Doors, The ECG A 081227940881 559094 21.98 3/24/17