6.1. Breaking the Electronic Sprawl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music-Week-1993-05-0

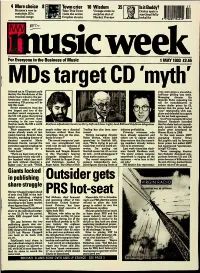

4 Morechoice 8 Town crier 10 Wisdom Kenyon'smaintain vowR3's to Take This Town Vintage comic is musical range visitsCroydon the streets active Marketsurprise Preview star of ■ ^ • H itmsKweek For Everyone in the Business of Music 1 MAY 1993 £2.65 iiistargetCO mftl17 Adestroy forced the eut foundationsin CD prices ofcould the half-hourtives were grillinggiven a lastone-and-a- week. wholeliamentary music selectindustry, committee the par- MalcolmManaging Field, director repeating hisSir toldexaraining this week. CD pricing will be reducecall for dealer manufacturers prices by £2,to twoSenior largest executives and two from of the "cosy"denied relationshipthat his group with had sup- a thesmallest UK will record argue companies that pricing in pliera and defended its support investingchanges willin theprevent new talentthem RichardOur Price Handover managing conceded director thatleader has in mademusic. the UK a world Kaufman adjudicates (centre) as Perry (left) and Ames (right) head EMI and PolyGram délégations atelythat his passed chain hadon thenot immedi-reduced claimsTheir alreadyarguments made will at echolast businesspeople rather without see athose classical fine Tradingmoned. has also been sum- industryPrivately profitability. witnesses who Warnerdealer Musicprice inintroduced 1988. by Goulden,week's hearing. managing Retailer director Alan of recordingsdards for years that ?" set the stan- RobinTemple Morton, managing whose director label othershave alreadyyet to appearedappear admit and managingIn the nextdirector session BrianHMV Discountclassical Centre,specialist warned Music the tionThe was record strengthened companies' posi-last says,spécialisés "We're intrying Scottish to put folk, out teedeep members concem thatalready the commit-believe lowerMcLaughlin prices saidbut addedhe favoured HMV thecommittee music against industry singling for outa independentsweek with the late inclusionHyperion of erwise.music that l'm won't putting be heard oth-out CDsLast to beweek overpriced, committee chair- hadly high" experienced CD sales. -

Master Thesis the Changes in the Dutch Dance Music Industry Value

Master thesis The changes in the Dutch dance music industry value chain due to the digitalization of the music industry University of Groningen, faculty of Management & Organization Msc in Business Administration: Strategy & Innovation Author: Meike Biesma Student number: 1677756 Supervisor: Iván Orosa Paleo Date: 11 May 2009 Abstract During this research, the Dutch dance music industry was investigated. Because of the changes in the music industry, that are caused by the internet, the Dutch dance music industry has changed accordingly. By means of a qualitative research design, a literature study was done as well as personal interviews were performed in order to investigate what changes occurred in the Dutch dance music industry value chain. Where the Dutch dance music industry used to be a physical oriented industry, the digital music format has replaced the physical product. This has had major implications for actors in the industry, because the digital sales have not compensated the losses that were caused by the decrease in physical sales. The main trigger is music piracy. Digital music is difficult to protect, and it was found that almost 99% of all music available on the internet was illegal. Because of the decline in music sales revenues, actors in the industry have had to change their strategies to remain profitable. New actors have emerged, like digital music retailers and digital music distributors. Also, record companies have changed their business model by vertically integrating other tasks within the dance music industry value chain to be able to stay profitable. It was concluded that the value chain of the Dutch dance music industry has changed drastically because of the digitalization of the industry. -

Treble Culture

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN P A R T I FREQUENCY-RANGE AESTHETICS ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4411 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:53:21:53 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4422 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:54:21:54 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN CHAPTER 2 TREBLE CULTURE WAYNE MARSHALL We’ve all had those times where we’re stuck on the bus with some insuf- ferable little shit blaring out the freshest off erings from Da Urban Classix Colleckshun Volyoom: 53 (or whatevs) on a tinny set of Walkman phone speakers. I don’t really fi nd that kind of music off ensive, I’m just indiff er- ent towards it but every time I hear something like this it just winds me up how shit it sounds. Does audio quality matter to these kids? I mean, isn’t it nice to actually be able to hear all the diff erent parts of the track going on at a decent level of sound quality rather than it sounding like it was recorded in a pair of socks? —A commenter called “cassette” 1 . do the missing data matter when you’re listening on the train? —Jonathan Sterne (2006a:339) At the end of the fi rst decade of the twenty-fi rst century, with the possibilities for high-fi delity recording at a democratized high and “bass culture” more globally present than ever, we face the irony that people are listening to music, with increasing frequency if not ubiquity, primarily through small plastic -

Global Hip-Hop Class

AAAS 135b: GLOBAL HIP-HOP Wed 6:30-9:20 pm Mandel G03 Spring 2012 Wayne Marshall [email protected] office hours: by appointment DESCRIPTION Examining how hip-hop travels and is embraced, represented, and transformed in various locales around the world, this course approaches hip-hop as itself constituted by international flows and as a product and set of practices that circulate globally in complex ways, cast variously as American, African-American, and/or black, and recast through the cultural logics of the new spaces it enters, the soundscapes it permeates. A host of questions arise when we consider hip-hopʼs global scope and significance: What does the genre in its various forms (audio, video, sartorial, gestural) carry beyond the US? What do people bring to it in new local contexts? How are US notions of race and nation mediated by hip-hop's global reach? Why do some global (which is to say, local) hip-hop scenes fasten onto the genre's well-rehearsed focus on place, community, and righteous opposition to structural and representational forms of violence, while others appear more enamored with slick portrayals of hustler archetypes, cool machismo, and ruggedly individualist, conspicuous consumption? How can hip-hop circulate in such contradictory forms? In what ways do hip-hop scenes differ from North to South America, West to East Africa, Europe to Asia? What threads unite them? In pursuit of such questions, we will read across the emerging literature on global hip- hop as we explore the growing resources available via the internet, where websites and blogs, MySpace and YouTube and the like have facilitated a further efflorescence of international (and peer-to-peer) exchanges around hip-hop. -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

Read Or Download

afrique.q 7/15/02 12:36 PM Page 2 The tree of life that is reggae music in all its forms is deeply spreading its roots back into Afri- ca, idealized, championed and longed for in so many reggae anthems. African dancehall artists may very well represent the most exciting (and least- r e c o g n i z e d ) m o vement happening in dancehall today. Africa is so huge, culturally rich and diverse that it is difficult to generalize about the musical happenings. Yet a recent musical sampling of the continent shows that dancehall is begin- ning to emerge as a powerful African musical form in its own right. FromFrom thethe MotherlandMotherland....Danc....Danc By Lisa Poliak daara-j Coming primarily out of West Africa, artists such as Gambia’s Rebellion D’Recaller, Dancehall Masters and Senegal’s Daara-J, Pee GAMBIA Froiss and V.I.B. are creating their own sounds growing from a fertile musical and cultural Gambia is Africa’s cross-pollination that blends elements of hip- dancehall hot spot. hop, reggae and African rhythms such as Out of Gambia, Rebel- Senegalese mbalax, for instance. Most of lion D’Recaller and these artists have not yet spread their wings Dancehall Masters are on the international scene, especially in the creating music that is U.S., but all have the musical and lyrical skills less rap-influenced to explode globally. Chanting down Babylon, than what is coming these African artists are inspired by their out of Senegal. In Jamaican predecessors while making music Gambia, they’re basi- that is uniquely their own, praising Jah, Allah cally heavier on the and historical spiritual leaders. -

New Promo Pack 2021 4 1 1.Pdf

Promo Pack 2021 Danceparty247 was set up in April 2020 and is run by DJ Envy, DJ Wongy and DJ Te. It is a brand where DJ's and DJ/producers from around the world come together to stream weekly shows across the internet. As well as UK based DJ's we have DJs and producers from, Spain, Puerto Rico, Portugal, Egypt, Belgium, Czech Republic and South Africa. Danceparty247 streams across several platforms and across our own website danceparty247.club. We are PPL and PRS compliant on our website by using the Beathubz planform media player. We reach up to 10,000 unique listens a week. This is comprised of live listeners and views on recorded replays. Many of our shows attain 250-300+ concurrent listeners. In association with Type 2 Promotions we are looking to put on regular good quality events in several parts of the UK. Giving the opportunity for Danceparty247 DJ's to DJ Live. At the same time making sure that both the venue and ourselves mutually benefit from this arrangement. We are open to discussing any ideas you may have. We are looking in the first instance to put on a regular event once a month with yourselves. Given the opportunity we would like to arrange a Zoom meeting or WhatsApp video call with yourselves to discuss our proposal further. Benny Bereal, DJ Envy, DJ Wongy, DJ Te Email: [email protected] WhatsApp: Benny Bereal 07765083211 Simon Wright 07903557538 Martin Young 07851465067 Type2 Productions Benny Bereal I am an Actor, Writer, Director and Promoter. I have been working in the film and tv industry for 5 years and have worked on programmes on channels for the like of the BBC, ITV, CH5 and I have worked alongside names such as Pierce Brosnan, Dave Bautista, David Tennant and Margot Robbie. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

'Survival of 'Radio Culture'

Coventry University Coventry University Repository for the Virtual Environment (CURVE) Author name: Mudhai, O.F. Title: Survival of ‘radio culture’ in a converged networked new media environment. Article & version: Post-print Original citation & hyperlink: Mudhai, O.F. (2011) 'Survival of ‘radio culture’ in a converged networked new media environment' in Popular Media, Democracy and Development in Africa. ed. Herman Wasserman. London: Routledge: 253-268 http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415577946 Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Available in the CURVE Research Collection: October 2011 http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open Survival of ‘radio culture’ in a converged networked new media environment* Okoth Fred Mudhai ([email protected]) Coventry University Introduction With emphasis on popular music and related entertainment rather than democratic culture and identity politics, this chapter examines the extent to which radio remains significant in socio-cultural and political landscapes in Africa given the proliferation of newer information and communication technologies (ICTs) more recently enlivened by cell phones and social networking applications. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Garage House Music Whats up with That

Garage House Music whats up with that Future funk is a sample-based advancement of Nu-disco which formed out of the Vaporwave scene and genre in the early 2010s. It tends to be more energetic than vaporwave, including elements of French Home, Synth Funk, and making use of Vaporwave modifying techniques. A style coming from the mid- 2010s, often explained as a blend of UK garage and deep home with other elements and strategies from EDM, popularized in late 2014 into 2015, typically mixes deep/metallic/sax hooks with heavy drops somewhat like the ones discovered in future garage. One of the very first house categories with origins embeded in New York and New Jersey. It was named after the Paradise Garage bar in New york city that operated from 1977 to 1987 under the prominent resident DJ Larry Levan. Garage house established along with Chicago home and the outcome was home music sharing its resemblances, affecting each other. One contrast from Chicago house was that the vocals in garage house drew stronger impacts from gospel. Noteworthy examples consist of Adeva and Tony Humphries. Kristine W is an example of a musician involved with garage house outside the genre's origin of birth. Also understood as G-house, it includes very little 808 and 909 drum machine-driven tracks and often sexually explicit lyrics. See likewise: ghettotech, juke house, footwork. It integrates components of Chicago's ghetto house with electro, Detroit techno, Miami bass and UK garage. It includes four-on-the-floor rhythms and is normally faster than a lot of other dance music categories, at approximately 145 to 160 BPM. -

{Download PDF} Cultural Traditions in the United Kingdom

CULTURAL TRADITIONS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lynn Peppas | 32 pages | 24 Jul 2014 | Crabtree Publishing Co,Canada | 9780778703136 | English | New York, Canada Cultural Traditions in the United Kingdom PDF Book Retrieved 11 July It was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in and was launched by the post office as the K2 two years after. Under the Labour governments of the s and s most secondary modern and grammar schools were combined to become comprehensive schools. Due to the rise in the ownership of mobile phones among the population, the usage of the red telephone box has greatly declined over the past years. In , scouting in the UK experienced its biggest growth since , taking total membership to almost , We in Hollywood owe much to him. Pantomime often referred to as "panto" is a British musical comedy stage production, designed for family entertainment. From being a salad stop to housing a library of books, ingenious ways are sprouting up to save this icon from total extinction. The Tate galleries house the national collections of British and international modern art; they also host the famously controversial Turner Prize. Jenkins, Richard, ed. Non-European immigration in Britain has not moved toward a pattern of sharply-defined urban ethnic ghettoes. Media Radio Television Cinema. It is a small part of the tartan and is worn around the waist. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. At modern times the British music is one of the most developed and most influential in the world. Wolverhampton: Borderline Publications. Initially idealistic and patriotic in tone, as the war progressed the tone of the movement became increasingly sombre and pacifistic.