On Universally Easy Classes for NP-Complete Problems *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midterm Study Sheet for CS3719 Regular Languages and Finite

Midterm study sheet for CS3719 Regular languages and finite automata: • An alphabet is a finite set of symbols. Set of all finite strings over an alphabet Σ is denoted Σ∗.A language is a subset of Σ∗. Empty string is called (epsilon). • Regular expressions are built recursively starting from ∅, and symbols from Σ and closing under ∗ Union (R1 ∪ R2), Concatenation (R1 ◦ R2) and Kleene Star (R denoting 0 or more repetitions of R) operations. These three operations are called regular operations. • A Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) D is a 5-tuple (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ), where Q is a finite set of states, Σ is the alphabet, δ : Q × Σ → Q is the transition function, q0 is the start state, and F is the set of accept states. A DFA accepts a string if there exists a sequence of states starting with r0 = q0 and ending with rn ∈ F such that ∀i, 0 ≤ i < n, δ(ri, wi) = ri+1. The language of a DFA, denoted L(D) is the set of all and only strings that D accepts. • Deterministic finite automata are used in string matching algorithms such as Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm. • A language is called regular if it is recognized by some DFA. • ‘Theorem: The class of regular languages is closed under union, concatenation and Kleene star operations. • A non-deterministic finite automaton (NFA) is a 5-tuple (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ), where Q, Σ, q0 and F are as in the case of DFA, but the transition function δ is δ : Q × (Σ ∪ {}) → P(Q). -

Chapter 6 Formal Language Theory

Chapter 6 Formal Language Theory In this chapter, we introduce formal language theory, the computational theories of languages and grammars. The models are actually inspired by formal logic, enriched with insights from the theory of computation. We begin with the definition of a language and then proceed to a rough characterization of the basic Chomsky hierarchy. We then turn to a more de- tailed consideration of the types of languages in the hierarchy and automata theory. 6.1 Languages What is a language? Formally, a language L is defined as as set (possibly infinite) of strings over some finite alphabet. Definition 7 (Language) A language L is a possibly infinite set of strings over a finite alphabet Σ. We define Σ∗ as the set of all possible strings over some alphabet Σ. Thus L ⊆ Σ∗. The set of all possible languages over some alphabet Σ is the set of ∗ all possible subsets of Σ∗, i.e. 2Σ or ℘(Σ∗). This may seem rather simple, but is actually perfectly adequate for our purposes. 6.2 Grammars A grammar is a way to characterize a language L, a way to list out which strings of Σ∗ are in L and which are not. If L is finite, we could simply list 94 CHAPTER 6. FORMAL LANGUAGE THEORY 95 the strings, but languages by definition need not be finite. In fact, all of the languages we are interested in are infinite. This is, as we showed in chapter 2, also true of human language. Relating the material of this chapter to that of the preceding two, we can view a grammar as a logical system by which we can prove things. -

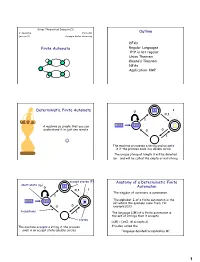

Deterministic Finite Automata 0 0,1 1

Great Theoretical Ideas in CS V. Adamchik CS 15-251 Outline Lecture 21 Carnegie Mellon University DFAs Finite Automata Regular Languages 0n1n is not regular Union Theorem Kleene’s Theorem NFAs Application: KMP 11 1 Deterministic Finite Automata 0 0,1 1 A machine so simple that you can 0111 111 1 ϵ understand it in just one minute 0 0 1 The machine processes a string and accepts it if the process ends in a double circle The unique string of length 0 will be denoted by ε and will be called the empty or null string accept states (F) Anatomy of a Deterministic Finite start state (q0) 11 0 Automaton 0,1 1 The singular of automata is automaton. 1 The alphabet Σ of a finite automaton is the 0111 111 1 ϵ set where the symbols come from, for 0 0 example {0,1} transitions 1 The language L(M) of a finite automaton is the set of strings that it accepts states L(M) = {x∈Σ: M accepts x} The machine accepts a string if the process It’s also called the ends in an accept state (double circle) “language decided/accepted by M”. 1 The Language L(M) of Machine M The Language L(M) of Machine M 0 0 0 0,1 1 q 0 q1 q0 1 1 What language does this DFA decide/accept? L(M) = All strings of 0s and 1s The language of a finite automaton is the set of strings that it accepts L(M) = { w | w has an even number of 1s} M = (Q, Σ, , q0, F) Q = {q0, q1, q2, q3} Formal definition of DFAs where Σ = {0,1} A finite automaton is a 5-tuple M = (Q, Σ, , q0, F) q0 Q is start state Q is the finite set of states F = {q1, q2} Q accept states : Q Σ → Q transition function Σ is the alphabet : Q Σ → Q is the transition function q 1 0 1 0 1 0,1 q0 Q is the start state q0 q0 q1 1 q q1 q2 q2 F Q is the set of accept states 0 M q2 0 0 q2 q3 q2 q q q 1 3 0 2 L(M) = the language of machine M q3 = set of all strings machine M accepts EXAMPLE Determine the language An automaton that accepts all recognized by and only those strings that contain 001 1 0,1 0,1 0 1 0 0 0 1 {0} {00} {001} 1 L(M)={1,11,111, …} 2 Membership problem Determine the language decided by Determine whether some word belongs to the language. -

6.045 Final Exam Name

6.045J/18.400J: Automata, Computability and Complexity Prof. Nancy Lynch 6.045 Final Exam May 20, 2005 Name: • Please write your name on each page. • This exam is open book, open notes. • There are two sheets of scratch paper at the end of this exam. • Questions vary substantially in difficulty. Use your time accordingly. • If you cannot produce a full proof, clearly state partial results for partial credit. • Good luck! Part Problem Points Grade Part I 1–10 50 1 20 2 15 3 25 Part II 4 15 5 15 6 10 Total 150 final-1 Name: Part I Multiple Choice Questions. (50 points, 5 points for each question) For each question, any number of the listed answersClearly may place be correct. an “X” in the box next to each of the answers that you are selecting. Problem 1: Which of the following are true statements about regular and nonregular languages? (All lan guages are over the alphabet{0, 1}) IfL1 ⊆ L2 andL2 is regular, thenL1 must be regular. IfL1 andL2 are nonregular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. IfL1 is nonregular, then the complementL 1 must of also be nonregular. IfL1 is regular,L2 is nonregular, andL1 ∩ L2 is nonregular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. IfL1 is regular,L2 is nonregular, andL1 ∩ L2 is regular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. Problem 2: Which of the following are guaranteed to be regular languages ? ∗ L2 = {ww : w ∈{0, 1}}. L2 = {ww : w ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. L2 = {w : ww ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. L2 = {w : for somex,| w| = |x| andwx ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. -

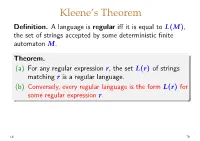

(A) for Any Regular Expression R, the Set L(R) of Strings

Kleene’s Theorem Definition. Alanguageisregular iff it is equal to L(M), the set of strings accepted by some deterministic finite automaton M. Theorem. (a) For any regular expression r,thesetL(r) of strings matching r is a regular language. (b) Conversely, every regular language is the form L(r) for some regular expression r. L6 79 Example of a regular language Recall the example DFA we used earlier: b a a a a M ! q0 q1 q2 q3 b b b In this case it’s not hard to see that L(M)=L(r) for r =(a|b)∗ aaa(a|b)∗ L6 80 Example M ! a 1 b 0 b a a 2 L(M)=L(r) for which regular expression r? Guess: r = a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ L6 81 Example M ! a 1 b 0 b a a 2 L(M)=L(r) for which regular expression r? Guess: r = a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ since baabaa ∈ L(M) WRONG! but baabaa ̸∈ L(a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ ) We need an algorithm for constructing a suitable r for each M (plus a proof that it is correct). L6 81 Lemma. Given an NFA M =(Q, Σ, δ, s, F),foreach subset S ⊆ Q and each pair of states q, q′ ∈ Q,thereisa S regular expression rq,q′ satisfying S Σ∗ u ∗ ′ L(rq,q′ )={u ∈ | q −→ q in M with all inter- mediate states of the sequence of transitions in S}. Hence if the subset F of accepting states has k distinct elements, q1,...,qk say, then L(M)=L(r) with r ! r1|···|rk where Q ri = rs,qi (i = 1, . -

Formal Languages We’Ll Use the English Language As a Running Example

Formal Languages We’ll use the English language as a running example. Definitions. Examples. A string is a finite set of symbols, where • each symbol belongs to an alphabet de- noted by Σ. The set of all strings that can be constructed • from an alphabet Σ is Σ ∗. If x, y are two strings of lengths x and y , • then: | | | | – xy or x y is the concatenation of x and y, so the◦ length, xy = x + y | | | | | | – (x)R is the reversal of x – the kth-power of x is k ! if k =0 x = k 1 x − x, if k>0 ! ◦ – equal, substring, prefix, suffix are de- fined in the expected ways. – Note that the language is not the same language as !. ∅ 73 Operations on Languages Suppose that LE is the English language and that LF is the French language over an alphabet Σ. Complementation: L = Σ L • ∗ − LE is the set of all words that do NOT belong in the english dictionary . Union: L1 L2 = x : x L1 or x L2 • ∪ { ∈ ∈ } L L is the set of all english and french words. E ∪ F Intersection: L1 L2 = x : x L1 and x L2 • ∩ { ∈ ∈ } LE LF is the set of all words that belong to both english and∩ french...eg., journal Concatenation: L1 L2 is the set of all strings xy such • ◦ that x L1 and y L2 ∈ ∈ Q: What is an example of a string in L L ? E ◦ F goodnuit Q: What if L or L is ? What is L L ? E F ∅ E ◦ F ∅ 74 Kleene star: L∗. -

Using Jflap in Academics to Understand Automata Theory in a Better Way

International Journal of Advances in Electronics and Computer Science, ISSN: 2393-2835 Volume-5, Issue-5, May.-2018 http://iraj.in USING JFLAP IN ACADEMICS TO UNDERSTAND AUTOMATA THEORY IN A BETTER WAY KAVITA TEWANI Assistant Professor, Institute of Technology, Nirma University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - As it is been observed that the things get much easier once we visualize it and hence this paper is just a step towards it. Usually many subjects in computer engineering curriculum like algorithms, data structures, and theory of computation are taught theoretically however it lacks the visualization that may help students to understand the concepts in a better way. The paper shows some of the practices on tool called JFLAP (Java Formal Languages and Automata Package) and the statistics on how it affected the students to learn the concepts easily. The diagrammatic representation is used to help the theory mentioned. Keywords - Automata, JFLAP, Grammar, Chomsky Heirarchy , Turing Machine, DFA, NFA I. INTRODUCTION visualization and interaction in the course is enhanced through the popular software tools[6,7]. The proper The theory of computation is a basic course in use of JFLAP and instructions are provided in the computer engineering discipline. It is the subject manual “JFLAP activities for Formal Languages and which is been taught theoretically and hands-on Automata” by Peter Linz and Susan Rodger. It problems are given to the students to enhance the includes the theoretical approach and their understanding but it lacks the programming implementation in JFLAP. [10] assignment. However the subject is the base for creation of compilers and therefore should be given III. -

Chapter 3: Lexing and Parsing

Chapter 3: Lexing and Parsing Aarne Ranta Slides for the book "Implementing Programming Languages. An Introduction to Compilers and Interpreters", College Publications, 2012. Lexing and Parsing* Deeper understanding of the previous chapter Regular expressions and finite automata • the compilation procedure • why automata may explode in size • why parentheses cannot be matched by finite automata Context-free grammars and parsing algorithms. • LL and LR parsing • why context-free grammars cannot alone specify languages • why conflicts arise The standard tools The code generated by BNFC is processed by other tools: • Lex (Alex for Haskell, JLex for Java, Flex for C) • Yacc (Happy for Haskell, Cup for Java, Bison for C) Lex and YACC are the original tools from the early 1970's. They are based on the theory of formal languages: • Lex code is regular expressions, converted to finite automata. • Yacc code is context-free grammars, converted to LALR(1) parsers. The theory of formal languages A formal language is, mathematically, just any set of sequences of symbols, Symbols are just elements from any finite set, such as the 128 7-bit ASCII characters. Programming languages are examples of formal languages. In the theory, usually simpler languages are studied. But the complexity of real languages is mostly due to repetitions of simple well-known patterns. Regular languages A regular language is, like any formal language, a set of strings, i.e. sequences of symbols, from a finite set of symbols called the alphabet. All regular languages can be defined by regular expressions in the following set: expression language 'a' fag AB fabja 2 [[A]]; b 2 [[B]]g A j B [[A]] [ [[B]] A* fa1a2 : : : anjai 2 [[A]]; n ≥ 0g eps fg (empty string) [[A]] is the set corresponding to the expression A. -

Regular Expressions

Regular Expressions A regular expression describes a language using three operations. Regular Expressions A regular expression (RE) describes a language. It uses the three regular operations. These are called union/or, concatenation and star. Brackets ( and ) are used for grouping, just as in normal math. Goddard 2: 2 Union The symbol + means union or or. Example: 0 + 1 means either a zero or a one. Goddard 2: 3 Concatenation The concatenation of two REs is obtained by writing the one after the other. Example: (0 + 1) 0 corresponds to f00; 10g. (0 + 1)(0 + ") corresponds to f00; 0; 10; 1g. Goddard 2: 4 Star The symbol ∗ is pronounced star and means zero or more copies. Example: a∗ corresponds to any string of a’s: f"; a; aa; aaa;:::g. ∗ (0 + 1) corresponds to all binary strings. Goddard 2: 5 Example An RE for the language of all binary strings of length at least 2 that begin and end in the same symbol. Goddard 2: 6 Example An RE for the language of all binary strings of length at least 2 that begin and end in the same symbol. ∗ ∗ 0(0 + 1) 0 + 1(0 + 1) 1 Note precedence of regular operators: star al- ways refers to smallest piece it can, or to largest piece it can. Goddard 2: 7 Example Consider the regular expression ∗ ∗ ((0 + 1) 1 + ")(00) 00 Goddard 2: 8 Example Consider the regular expression ∗ ∗ ((0 + 1) 1 + ")(00) 00 This RE is for the set of all binary strings that end with an even nonzero number of 0’s. -

Regular Languages Context-Free Languages

Regular Languages continued Context-Free Languages CS F331 Programming Languages CSCE A331 Programming Language Concepts Lecture Slides Wednesday, January 23, 2019 Glenn G. Chappell Department of Computer Science University of Alaska Fairbanks [email protected] © 2017–2019 Glenn G. Chappell Review Formal Languages & Grammars Grammar Derivation of xxxxyy Each line is a 1. S → xxSy production. S 1 2. S → a xxSy 1 3. S → ε xxxxSyy 3 xxxxyy To use a grammar: No “ε” § Begin with the start symbol. appears here. § Repeat: § Apply a production, replacing the left-hand side with the right-hand side. § We can stop only when there are no more nonterminals. The result is a derivation of the final string. The language generated by a grammar consists of all strings for which there is a derivation. 23 Jan 2019 CS F331 / CSCE A331 Spring 2019 2 Review Regular Languages — Regular Grammars & Languages A regular grammar is a grammar, each of whose productions looks like one of the following. We allow a production using the same A → ε A → b A → bC nonterminal twice: A → bA A regular language is a language that is generated by some regular grammar. This grammar is regular: S → ε S → t S → xB B → yS The language it generates is therefore a regular language: {ε, xy, xyxy, xyxyxy, …, t, xyt, xyxyt, xyxyxyt, …} 23 Jan 2019 CS F331 / CSCE A331 Spring 2019 3 Review Regular Languages — Finite Automata [1/3] A deterministic finite automaton (Latin plural “automata”), or DFA, is a kind of recognizer for regular languages. A DFA has: § A finite collection of states. -

The Limits of Regular Languages

The Limits of Regular Languages Announcements ● Midterm tomorrow night in Hewlett 200/201, 7PM – 10PM. ● Open-book, open-note, open-computer, closed-network. ● Covers material up to and including DFAs. Regular Expressions The Regular Expressions ● Goal: Assemble all regular languages from smaller building blocks! ● Atomic regular expressions: Ø ε a ● Compound regular expressions: R1R2 R1 | R2 R* (R) Operator Precedence ● Regular expression operator precedence: (R) R* R1R2 R1 | R2 ● ab*c|d is parsed as ((a(b*))c)|d Regular Expressions are Awesome ● Let Σ = { a, ., @ }, where a represents “some letter.” ● Regular expression for email addresses: aa* (.aa*)* @ aa*.aa* (.aa*)* [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Regular Expressions are Awesome ● Let Σ = { a, ., @ }, where a represents “some letter.” ● Regular expression for email addresses: a+(.a+)*@a+(.a+)+ [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Regular Expressions are Awesome a+(.a+)*@a+(.a+)+ @, . a, @, . @, . @, . q 2 q8 q7 @ ., @ . a @ @, . a start q a q @ q a . a 0 1 3 q04 q5 q6 a a a The Power of Regular Expressions Theorem: If R is a regular expression, then ℒ(R) is regular. Proof idea: Induction over the structure of regular expressions. Atomic regular expressions are the base cases, and the inductive step handles each way of combining regular expressions. A Marvelous Construction ● To show that any language described by a regular expression is regular, we show how to convert a regular expression into an NFA. ● Theorem: For any regular expression R, there is an NFA N such that ● ℒ(R) = ℒ(N) ● N has exactly one accepting state. -

Generalized Nondeterministic Finite Automaton (GNFA); It Can Be Shown (We Omit the Proof for Brevity) That Any DFA Can Be Converted Into a GNFA

Regular Languages Contents • Finite Automata • Non-Determinism • Regular Expressions • Non-Regular Languages Finite Automata • The theory of computation begins with the basic question: What is a computer? • In our subsequent discussion we introduce various types of abstract, computational models. We begin with the simplest such model: a finite state automaton (FA), plural: automata. • Finite automata are good models for computers with an extremely limited amount of memory (e.g. a basic controller). As we will show, this limited memory significantly limits what is computable by a FA. Finite Automata • The figure above is called a state diagram of an automaton, which we will call M. • M has three states, labeled q1, q2 and q3. The start state, q1, is indicated by the arrow pointing at it from nowhere. The accept state, q2, is the one with a double circle. The arrows going from one state to another are called transitions. • When the automaton receives an input string such as 1101, it processes that string and produces an output; the output is either accept or reject. Finite Automata • For example, when we feed the input string 1101 into M, the processing proceeds as follows: 1. Start in state q1 2. Read 1, follow transition from q1 to q2. 3. Read 1, follow transition from q2 to q2. 4. Read 0, follow transition from q2 to q3. 5. Read 1, follow transition from q3 to q2. 6. Accept because M is in accept state q2 at the end of the input. Finite Automata • Formally, a finite automaton is a 5-tuple 푄, Σ, δ, 푞0, 퐹 , where: 1.