Chapter 3: Lexing and Parsing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midterm Study Sheet for CS3719 Regular Languages and Finite

Midterm study sheet for CS3719 Regular languages and finite automata: • An alphabet is a finite set of symbols. Set of all finite strings over an alphabet Σ is denoted Σ∗.A language is a subset of Σ∗. Empty string is called (epsilon). • Regular expressions are built recursively starting from ∅, and symbols from Σ and closing under ∗ Union (R1 ∪ R2), Concatenation (R1 ◦ R2) and Kleene Star (R denoting 0 or more repetitions of R) operations. These three operations are called regular operations. • A Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) D is a 5-tuple (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ), where Q is a finite set of states, Σ is the alphabet, δ : Q × Σ → Q is the transition function, q0 is the start state, and F is the set of accept states. A DFA accepts a string if there exists a sequence of states starting with r0 = q0 and ending with rn ∈ F such that ∀i, 0 ≤ i < n, δ(ri, wi) = ri+1. The language of a DFA, denoted L(D) is the set of all and only strings that D accepts. • Deterministic finite automata are used in string matching algorithms such as Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm. • A language is called regular if it is recognized by some DFA. • ‘Theorem: The class of regular languages is closed under union, concatenation and Kleene star operations. • A non-deterministic finite automaton (NFA) is a 5-tuple (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ), where Q, Σ, q0 and F are as in the case of DFA, but the transition function δ is δ : Q × (Σ ∪ {}) → P(Q). -

Backtrack Parsing Context-Free Grammar Context-Free Grammar

Context-free Grammar Problems with Regular Context-free Grammar Language and Is English a regular language? Bad question! We do not even know what English is! Two eggs and bacon make(s) a big breakfast Backtrack Parsing Can you slide me the salt? He didn't ought to do that But—No! Martin Kay I put the wine you brought in the fridge I put the wine you brought for Sandy in the fridge Should we bring the wine you put in the fridge out Stanford University now? and University of the Saarland You said you thought nobody had the right to claim that they were above the law Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 1 Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 2 Problems with Regular Problems with Regular Language Language You said you thought nobody had the right to claim [You said you thought [nobody had the right [to claim that they were above the law that [they were above the law]]]] Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 3 Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 4 Problems with Regular Context-free Grammar Language Nonterminal symbols ~ grammatical categories Is English mophology a regular language? Bad question! We do not even know what English Terminal Symbols ~ words morphology is! They sell collectables of all sorts Productions ~ (unordered) (rewriting) rules This concerns unredecontaminatability Distinguished Symbol This really is an untiable knot. But—Probably! (Not sure about Swahili, though) Not all that important • Terminals and nonterminals are disjoint • Distinguished symbol Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 5 Martin Kay Context-free Grammar 6 Context-free Grammar Context-free -

Chapter 6 Formal Language Theory

Chapter 6 Formal Language Theory In this chapter, we introduce formal language theory, the computational theories of languages and grammars. The models are actually inspired by formal logic, enriched with insights from the theory of computation. We begin with the definition of a language and then proceed to a rough characterization of the basic Chomsky hierarchy. We then turn to a more de- tailed consideration of the types of languages in the hierarchy and automata theory. 6.1 Languages What is a language? Formally, a language L is defined as as set (possibly infinite) of strings over some finite alphabet. Definition 7 (Language) A language L is a possibly infinite set of strings over a finite alphabet Σ. We define Σ∗ as the set of all possible strings over some alphabet Σ. Thus L ⊆ Σ∗. The set of all possible languages over some alphabet Σ is the set of ∗ all possible subsets of Σ∗, i.e. 2Σ or ℘(Σ∗). This may seem rather simple, but is actually perfectly adequate for our purposes. 6.2 Grammars A grammar is a way to characterize a language L, a way to list out which strings of Σ∗ are in L and which are not. If L is finite, we could simply list 94 CHAPTER 6. FORMAL LANGUAGE THEORY 95 the strings, but languages by definition need not be finite. In fact, all of the languages we are interested in are infinite. This is, as we showed in chapter 2, also true of human language. Relating the material of this chapter to that of the preceding two, we can view a grammar as a logical system by which we can prove things. -

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: the Power of Dynamic Analysis

Adaptive LL(*) Parsing: The Power of Dynamic Analysis Terence Parr Sam Harwell Kathleen Fisher University of San Francisco University of Texas at Austin Tufts University [email protected] [email protected] kfi[email protected] Abstract PEGs are unambiguous by definition but have a quirk where Despite the advances made by modern parsing strategies such rule A ! a j ab (meaning “A matches either a or ab”) can never as PEG, LL(*), GLR, and GLL, parsing is not a solved prob- match ab since PEGs choose the first alternative that matches lem. Existing approaches suffer from a number of weaknesses, a prefix of the remaining input. Nested backtracking makes de- including difficulties supporting side-effecting embedded ac- bugging PEGs difficult. tions, slow and/or unpredictable performance, and counter- Second, side-effecting programmer-supplied actions (muta- intuitive matching strategies. This paper introduces the ALL(*) tors) like print statements should be avoided in any strategy that parsing strategy that combines the simplicity, efficiency, and continuously speculates (PEG) or supports multiple interpreta- predictability of conventional top-down LL(k) parsers with the tions of the input (GLL and GLR) because such actions may power of a GLR-like mechanism to make parsing decisions. never really take place [17]. (Though DParser [24] supports The critical innovation is to move grammar analysis to parse- “final” actions when the programmer is certain a reduction is time, which lets ALL(*) handle any non-left-recursive context- part of an unambiguous final parse.) Without side effects, ac- free grammar. ALL(*) is O(n4) in theory but consistently per- tions must buffer data for all interpretations in immutable data forms linearly on grammars used in practice, outperforming structures or provide undo actions. -

Deterministic Finite Automata 0 0,1 1

Great Theoretical Ideas in CS V. Adamchik CS 15-251 Outline Lecture 21 Carnegie Mellon University DFAs Finite Automata Regular Languages 0n1n is not regular Union Theorem Kleene’s Theorem NFAs Application: KMP 11 1 Deterministic Finite Automata 0 0,1 1 A machine so simple that you can 0111 111 1 ϵ understand it in just one minute 0 0 1 The machine processes a string and accepts it if the process ends in a double circle The unique string of length 0 will be denoted by ε and will be called the empty or null string accept states (F) Anatomy of a Deterministic Finite start state (q0) 11 0 Automaton 0,1 1 The singular of automata is automaton. 1 The alphabet Σ of a finite automaton is the 0111 111 1 ϵ set where the symbols come from, for 0 0 example {0,1} transitions 1 The language L(M) of a finite automaton is the set of strings that it accepts states L(M) = {x∈Σ: M accepts x} The machine accepts a string if the process It’s also called the ends in an accept state (double circle) “language decided/accepted by M”. 1 The Language L(M) of Machine M The Language L(M) of Machine M 0 0 0 0,1 1 q 0 q1 q0 1 1 What language does this DFA decide/accept? L(M) = All strings of 0s and 1s The language of a finite automaton is the set of strings that it accepts L(M) = { w | w has an even number of 1s} M = (Q, Σ, , q0, F) Q = {q0, q1, q2, q3} Formal definition of DFAs where Σ = {0,1} A finite automaton is a 5-tuple M = (Q, Σ, , q0, F) q0 Q is start state Q is the finite set of states F = {q1, q2} Q accept states : Q Σ → Q transition function Σ is the alphabet : Q Σ → Q is the transition function q 1 0 1 0 1 0,1 q0 Q is the start state q0 q0 q1 1 q q1 q2 q2 F Q is the set of accept states 0 M q2 0 0 q2 q3 q2 q q q 1 3 0 2 L(M) = the language of machine M q3 = set of all strings machine M accepts EXAMPLE Determine the language An automaton that accepts all recognized by and only those strings that contain 001 1 0,1 0,1 0 1 0 0 0 1 {0} {00} {001} 1 L(M)={1,11,111, …} 2 Membership problem Determine the language decided by Determine whether some word belongs to the language. -

6.045 Final Exam Name

6.045J/18.400J: Automata, Computability and Complexity Prof. Nancy Lynch 6.045 Final Exam May 20, 2005 Name: • Please write your name on each page. • This exam is open book, open notes. • There are two sheets of scratch paper at the end of this exam. • Questions vary substantially in difficulty. Use your time accordingly. • If you cannot produce a full proof, clearly state partial results for partial credit. • Good luck! Part Problem Points Grade Part I 1–10 50 1 20 2 15 3 25 Part II 4 15 5 15 6 10 Total 150 final-1 Name: Part I Multiple Choice Questions. (50 points, 5 points for each question) For each question, any number of the listed answersClearly may place be correct. an “X” in the box next to each of the answers that you are selecting. Problem 1: Which of the following are true statements about regular and nonregular languages? (All lan guages are over the alphabet{0, 1}) IfL1 ⊆ L2 andL2 is regular, thenL1 must be regular. IfL1 andL2 are nonregular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. IfL1 is nonregular, then the complementL 1 must of also be nonregular. IfL1 is regular,L2 is nonregular, andL1 ∩ L2 is nonregular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. IfL1 is regular,L2 is nonregular, andL1 ∩ L2 is regular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. Problem 2: Which of the following are guaranteed to be regular languages ? ∗ L2 = {ww : w ∈{0, 1}}. L2 = {ww : w ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. L2 = {w : ww ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. L2 = {w : for somex,| w| = |x| andwx ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. -

Sequence Alignment/Map Format Specification

Sequence Alignment/Map Format Specification The SAM/BAM Format Specification Working Group 3 Jun 2021 The master version of this document can be found at https://github.com/samtools/hts-specs. This printing is version 53752fa from that repository, last modified on the date shown above. 1 The SAM Format Specification SAM stands for Sequence Alignment/Map format. It is a TAB-delimited text format consisting of a header section, which is optional, and an alignment section. If present, the header must be prior to the alignments. Header lines start with `@', while alignment lines do not. Each alignment line has 11 mandatory fields for essential alignment information such as mapping position, and variable number of optional fields for flexible or aligner specific information. This specification is for version 1.6 of the SAM and BAM formats. Each SAM and BAMfilemay optionally specify the version being used via the @HD VN tag. For full version history see Appendix B. Unless explicitly specified elsewhere, all fields are encoded using 7-bit US-ASCII 1 in using the POSIX / C locale. Regular expressions listed use the POSIX / IEEE Std 1003.1 extended syntax. 1.1 An example Suppose we have the following alignment with bases in lowercase clipped from the alignment. Read r001/1 and r001/2 constitute a read pair; r003 is a chimeric read; r004 represents a split alignment. Coor 12345678901234 5678901234567890123456789012345 ref AGCATGTTAGATAA**GATAGCTGTGCTAGTAGGCAGTCAGCGCCAT +r001/1 TTAGATAAAGGATA*CTG +r002 aaaAGATAA*GGATA +r003 gcctaAGCTAA +r004 ATAGCT..............TCAGC -r003 ttagctTAGGC -r001/2 CAGCGGCAT The corresponding SAM format is:2 1Charset ANSI X3.4-1968 as defined in RFC1345. -

Lexing and Parsing with ANTLR4

Lab 2 Lexing and Parsing with ANTLR4 Objective • Understand the software architecture of ANTLR4. • Be able to write simple grammars and correct grammar issues in ANTLR4. EXERCISE #1 Lab preparation Ï In the cap-labs directory: git pull will provide you all the necessary files for this lab in TP02. You also have to install ANTLR4. 2.1 User install for ANTLR4 and ANTLR4 Python runtime User installation steps: mkdir ~/lib cd ~/lib wget http://www.antlr.org/download/antlr-4.7-complete.jar pip3 install antlr4-python3-runtime --user Then in your .bashrc: export CLASSPATH=".:$HOME/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar:$CLASSPATH" export ANTLR4="java -jar $HOME/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar" alias antlr4="java -jar $HOME/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar" alias grun='java org.antlr.v4.gui.TestRig' Then source your .bashrc: source ~/.bashrc 2.2 Structure of a .g4 file and compilation Links to a bit of ANTLR4 syntax : • Lexical rules (extended regular expressions): https://github.com/antlr/antlr4/blob/4.7/doc/ lexer-rules.md • Parser rules (grammars) https://github.com/antlr/antlr4/blob/4.7/doc/parser-rules.md The compilation of a given .g4 (for the PYTHON back-end) is done by the following command line: java -jar ~/lib/antlr-4.7-complete.jar -Dlanguage=Python3 filename.g4 or if you modified your .bashrc properly: antlr4 -Dlanguage=Python3 filename.g4 2.3 Simple examples with ANTLR4 EXERCISE #2 Demo files Ï Work your way through the five examples in the directory demo_files: Aurore Alcolei, Laure Gonnord, Valentin Lorentz. 1/4 ENS de Lyon, Département Informatique, M1 CAP Lab #2 – Automne 2017 ex1 with ANTLR4 + Java : A very simple lexical analysis1 for simple arithmetic expressions of the form x+3. -

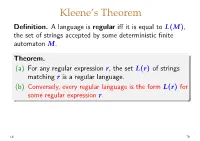

(A) for Any Regular Expression R, the Set L(R) of Strings

Kleene’s Theorem Definition. Alanguageisregular iff it is equal to L(M), the set of strings accepted by some deterministic finite automaton M. Theorem. (a) For any regular expression r,thesetL(r) of strings matching r is a regular language. (b) Conversely, every regular language is the form L(r) for some regular expression r. L6 79 Example of a regular language Recall the example DFA we used earlier: b a a a a M ! q0 q1 q2 q3 b b b In this case it’s not hard to see that L(M)=L(r) for r =(a|b)∗ aaa(a|b)∗ L6 80 Example M ! a 1 b 0 b a a 2 L(M)=L(r) for which regular expression r? Guess: r = a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ L6 81 Example M ! a 1 b 0 b a a 2 L(M)=L(r) for which regular expression r? Guess: r = a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ since baabaa ∈ L(M) WRONG! but baabaa ̸∈ L(a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ ) We need an algorithm for constructing a suitable r for each M (plus a proof that it is correct). L6 81 Lemma. Given an NFA M =(Q, Σ, δ, s, F),foreach subset S ⊆ Q and each pair of states q, q′ ∈ Q,thereisa S regular expression rq,q′ satisfying S Σ∗ u ∗ ′ L(rq,q′ )={u ∈ | q −→ q in M with all inter- mediate states of the sequence of transitions in S}. Hence if the subset F of accepting states has k distinct elements, q1,...,qk say, then L(M)=L(r) with r ! r1|···|rk where Q ri = rs,qi (i = 1, . -

Compiler Design

CCOOMMPPIILLEERR DDEESSIIGGNN -- PPAARRSSEERR http://www.tutorialspoint.com/compiler_design/compiler_design_parser.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com In the previous chapter, we understood the basic concepts involved in parsing. In this chapter, we will learn the various types of parser construction methods available. Parsing can be defined as top-down or bottom-up based on how the parse-tree is constructed. Top-Down Parsing We have learnt in the last chapter that the top-down parsing technique parses the input, and starts constructing a parse tree from the root node gradually moving down to the leaf nodes. The types of top-down parsing are depicted below: Recursive Descent Parsing Recursive descent is a top-down parsing technique that constructs the parse tree from the top and the input is read from left to right. It uses procedures for every terminal and non-terminal entity. This parsing technique recursively parses the input to make a parse tree, which may or may not require back-tracking. But the grammar associated with it ifnotleftfactored cannot avoid back- tracking. A form of recursive-descent parsing that does not require any back-tracking is known as predictive parsing. This parsing technique is regarded recursive as it uses context-free grammar which is recursive in nature. Back-tracking Top- down parsers start from the root node startsymbol and match the input string against the production rules to replace them ifmatched. To understand this, take the following example of CFG: S → rXd | rZd X → oa | ea Z → ai For an input string: read, a top-down parser, will behave like this: It will start with S from the production rules and will match its yield to the left-most letter of the input, i.e. -

7.2 Finite State Machines Finite State Machines Are Another Way to Specify the Syntax of a Sentence in a Lan- Guage

32397_CH07_331_388.qxd 1/14/09 5:01 PM Page 346 346 Chapter 7 Language Translation Principles Context Sensitivity of C++ It appears from Figure 7.8 that the C++ language is context-free. Every production rule has only a single nonterminal on the left side. This is in contrast to a context- sensitive grammar, which can have more than a single nonterminal on the left, as in Figure 7.3. Appearances are deceiving. Even though the grammar for this subset of C++, as well as the full standard C++ language, is context-free, the language itself has some context-sensitive aspects. Consider the grammar in Figure 7.3. How do its rules of production guarantee that the number of c’s at the end of a string must equal the number of a’s at the beginning of the string? Rules 1 and 2 guarantee that for each a generated, exactly one C will be generated. Rule 3 lets the C commute to the right of B. Finally, Rule 5 lets you substitute c for C in the context of having a b to the left of C. The lan- guage could not be specified by a context-free grammar because it needs Rules 3 and 5 to get the C’s to the end of the string. There are context-sensitive aspects of the C++ language that Figure 7.8 does not specify. For example, the definition of <parameter-list> allows any number of formal parameters, and the definition of <argument-expression-list> allows any number of actual parameters. -

Formal Languages We’Ll Use the English Language As a Running Example

Formal Languages We’ll use the English language as a running example. Definitions. Examples. A string is a finite set of symbols, where • each symbol belongs to an alphabet de- noted by Σ. The set of all strings that can be constructed • from an alphabet Σ is Σ ∗. If x, y are two strings of lengths x and y , • then: | | | | – xy or x y is the concatenation of x and y, so the◦ length, xy = x + y | | | | | | – (x)R is the reversal of x – the kth-power of x is k ! if k =0 x = k 1 x − x, if k>0 ! ◦ – equal, substring, prefix, suffix are de- fined in the expected ways. – Note that the language is not the same language as !. ∅ 73 Operations on Languages Suppose that LE is the English language and that LF is the French language over an alphabet Σ. Complementation: L = Σ L • ∗ − LE is the set of all words that do NOT belong in the english dictionary . Union: L1 L2 = x : x L1 or x L2 • ∪ { ∈ ∈ } L L is the set of all english and french words. E ∪ F Intersection: L1 L2 = x : x L1 and x L2 • ∩ { ∈ ∈ } LE LF is the set of all words that belong to both english and∩ french...eg., journal Concatenation: L1 L2 is the set of all strings xy such • ◦ that x L1 and y L2 ∈ ∈ Q: What is an example of a string in L L ? E ◦ F goodnuit Q: What if L or L is ? What is L L ? E F ∅ E ◦ F ∅ 74 Kleene star: L∗.