Deterministic Finite Automata 0 0,1 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midterm Study Sheet for CS3719 Regular Languages and Finite

Midterm study sheet for CS3719 Regular languages and finite automata: • An alphabet is a finite set of symbols. Set of all finite strings over an alphabet Σ is denoted Σ∗.A language is a subset of Σ∗. Empty string is called (epsilon). • Regular expressions are built recursively starting from ∅, and symbols from Σ and closing under ∗ Union (R1 ∪ R2), Concatenation (R1 ◦ R2) and Kleene Star (R denoting 0 or more repetitions of R) operations. These three operations are called regular operations. • A Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) D is a 5-tuple (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ), where Q is a finite set of states, Σ is the alphabet, δ : Q × Σ → Q is the transition function, q0 is the start state, and F is the set of accept states. A DFA accepts a string if there exists a sequence of states starting with r0 = q0 and ending with rn ∈ F such that ∀i, 0 ≤ i < n, δ(ri, wi) = ri+1. The language of a DFA, denoted L(D) is the set of all and only strings that D accepts. • Deterministic finite automata are used in string matching algorithms such as Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm. • A language is called regular if it is recognized by some DFA. • ‘Theorem: The class of regular languages is closed under union, concatenation and Kleene star operations. • A non-deterministic finite automaton (NFA) is a 5-tuple (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ), where Q, Σ, q0 and F are as in the case of DFA, but the transition function δ is δ : Q × (Σ ∪ {}) → P(Q). -

Chapter 6 Formal Language Theory

Chapter 6 Formal Language Theory In this chapter, we introduce formal language theory, the computational theories of languages and grammars. The models are actually inspired by formal logic, enriched with insights from the theory of computation. We begin with the definition of a language and then proceed to a rough characterization of the basic Chomsky hierarchy. We then turn to a more de- tailed consideration of the types of languages in the hierarchy and automata theory. 6.1 Languages What is a language? Formally, a language L is defined as as set (possibly infinite) of strings over some finite alphabet. Definition 7 (Language) A language L is a possibly infinite set of strings over a finite alphabet Σ. We define Σ∗ as the set of all possible strings over some alphabet Σ. Thus L ⊆ Σ∗. The set of all possible languages over some alphabet Σ is the set of ∗ all possible subsets of Σ∗, i.e. 2Σ or ℘(Σ∗). This may seem rather simple, but is actually perfectly adequate for our purposes. 6.2 Grammars A grammar is a way to characterize a language L, a way to list out which strings of Σ∗ are in L and which are not. If L is finite, we could simply list 94 CHAPTER 6. FORMAL LANGUAGE THEORY 95 the strings, but languages by definition need not be finite. In fact, all of the languages we are interested in are infinite. This is, as we showed in chapter 2, also true of human language. Relating the material of this chapter to that of the preceding two, we can view a grammar as a logical system by which we can prove things. -

6.045 Final Exam Name

6.045J/18.400J: Automata, Computability and Complexity Prof. Nancy Lynch 6.045 Final Exam May 20, 2005 Name: • Please write your name on each page. • This exam is open book, open notes. • There are two sheets of scratch paper at the end of this exam. • Questions vary substantially in difficulty. Use your time accordingly. • If you cannot produce a full proof, clearly state partial results for partial credit. • Good luck! Part Problem Points Grade Part I 1–10 50 1 20 2 15 3 25 Part II 4 15 5 15 6 10 Total 150 final-1 Name: Part I Multiple Choice Questions. (50 points, 5 points for each question) For each question, any number of the listed answersClearly may place be correct. an “X” in the box next to each of the answers that you are selecting. Problem 1: Which of the following are true statements about regular and nonregular languages? (All lan guages are over the alphabet{0, 1}) IfL1 ⊆ L2 andL2 is regular, thenL1 must be regular. IfL1 andL2 are nonregular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. IfL1 is nonregular, then the complementL 1 must of also be nonregular. IfL1 is regular,L2 is nonregular, andL1 ∩ L2 is nonregular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. IfL1 is regular,L2 is nonregular, andL1 ∩ L2 is regular, thenL1 ∪ L2 must be nonregular. Problem 2: Which of the following are guaranteed to be regular languages ? ∗ L2 = {ww : w ∈{0, 1}}. L2 = {ww : w ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. L2 = {w : ww ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. L2 = {w : for somex,| w| = |x| andwx ∈ L1}, whereL1 is a regular language. -

1 Alphabets and Languages

1 Alphabets and Languages Look at handout 1 (inference rules for sets) and use the rules on some exam- ples like fag ⊆ ffagg fag 2 fa; bg, fag 2 ffagg, fag ⊆ ffagg, fag ⊆ fa; bg, a ⊆ ffagg, a 2 fa; bg, a 2 ffagg, a ⊆ fa; bg Example: To show fag ⊆ fa; bg, use inference rule L1 (first one on the left). This asks us to show a 2 fa; bg. To show this, use rule L5, which succeeds. To show fag 2 fa; bg, which rule applies? • The only one is rule L4. So now we have to either show fag = a or fag = b. Neither one works. • To show fag = a we have to show fag ⊆ a and a ⊆ fag by rule L8. The only rules that might work to show a ⊆ fag are L1, L2, and L3 but none of them match, so we fail. • There is another rule for this at the very end, but it also fails. • To show fag = b, we try the rules in a similar way, but they also fail. Therefore we cannot show that fag 2 fa; bg. This suggests that the state- ment fag 2 fa; bg is false. Suppose we have two set expressions only involving brackets, commas, the empty set, and variables, like fa; fb; cgg and fa; fc; bgg. Then there is an easy way to test if they are equal. If they can be made the same by • permuting elements of a set, and • deleting duplicate items of a set then they are equal, otherwise they are not equal. -

Context Free Languages II Announcement Announcement

Announcement • About homework #4 Context Free Languages II – The FA corresponding to the RE given in class may indeed already be minimal. – Non-regular language proofs CFLs and Regular Languages • Use Pumping Lemma • Homework session after lecture Announcement Before we begin • Note about homework #2 • Questions from last time? – For a deterministic FA, there must be a transition for every character from every state. Languages CFLs and Regular Languages • Recall. • Venn diagram of languages – What is a language? Is there – What is a class of languages? something Regular Languages out here? CFLs Finite Languages 1 Context Free Languages Context Free Grammars • Context Free Languages(CFL) is the next • Let’s formalize this a bit: class of languages outside of Regular – A context free grammar (CFG) is a 4-tuple: (V, Languages: Σ, S, P) where – Means for defining: Context Free Grammar • V is a set of variables Σ – Machine for accepting: Pushdown Automata • is a set of terminals • V and Σ are disjoint (I.e. V ∩Σ= ∅) •S ∈V, is your start symbol Context Free Grammars Context Free Grammars • Let’s formalize this a bit: • Let’s formalize this a bit: – Production rules – Production rules →β •Of the form A where • We say that the grammar is context-free since this ∈ –A V substitution can take place regardless of where A is. – β∈(V ∪∑)* string with symbols from V and ∑ α⇒* γ γ α • We say that γ can be derived from α in one step: • We write if can be derived from in zero –A →βis a rule or more steps. -

Kleene Algebra with Tests and Coq Tools for While Programs Damien Pous

Kleene Algebra with Tests and Coq Tools for While Programs Damien Pous To cite this version: Damien Pous. Kleene Algebra with Tests and Coq Tools for While Programs. Interactive Theorem Proving 2013, Jul 2013, Rennes, France. pp.180-196, 10.1007/978-3-642-39634-2_15. hal-00785969 HAL Id: hal-00785969 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00785969 Submitted on 7 Feb 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Kleene Algebra with Tests and Coq Tools for While Programs Damien Pous CNRS { LIP, ENS Lyon, UMR 5668 Abstract. We present a Coq library about Kleene algebra with tests, including a proof of their completeness over the appropriate notion of languages, a decision procedure for their equational theory, and tools for exploiting hypotheses of a certain kind in such a theory. Kleene algebra with tests make it possible to represent if-then-else state- ments and while loops in most imperative programming languages. They were actually introduced by Kozen as an alternative to propositional Hoare logic. We show how to exploit the corresponding Coq tools in the context of program verification by proving equivalences of while programs, correct- ness of some standard compiler optimisations, Hoare rules for partial cor- rectness, and a particularly challenging equivalence of flowchart schemes. -

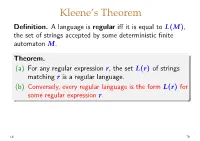

(A) for Any Regular Expression R, the Set L(R) of Strings

Kleene’s Theorem Definition. Alanguageisregular iff it is equal to L(M), the set of strings accepted by some deterministic finite automaton M. Theorem. (a) For any regular expression r,thesetL(r) of strings matching r is a regular language. (b) Conversely, every regular language is the form L(r) for some regular expression r. L6 79 Example of a regular language Recall the example DFA we used earlier: b a a a a M ! q0 q1 q2 q3 b b b In this case it’s not hard to see that L(M)=L(r) for r =(a|b)∗ aaa(a|b)∗ L6 80 Example M ! a 1 b 0 b a a 2 L(M)=L(r) for which regular expression r? Guess: r = a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ L6 81 Example M ! a 1 b 0 b a a 2 L(M)=L(r) for which regular expression r? Guess: r = a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ since baabaa ∈ L(M) WRONG! but baabaa ̸∈ L(a∗|a∗b(ab)∗ aaa∗ ) We need an algorithm for constructing a suitable r for each M (plus a proof that it is correct). L6 81 Lemma. Given an NFA M =(Q, Σ, δ, s, F),foreach subset S ⊆ Q and each pair of states q, q′ ∈ Q,thereisa S regular expression rq,q′ satisfying S Σ∗ u ∗ ′ L(rq,q′ )={u ∈ | q −→ q in M with all inter- mediate states of the sequence of transitions in S}. Hence if the subset F of accepting states has k distinct elements, q1,...,qk say, then L(M)=L(r) with r ! r1|···|rk where Q ri = rs,qi (i = 1, . -

Context-Free Languages ∗

Chapter 17: Context-Free Languages ¤ Peter Cappello Department of Computer Science University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 [email protected] ² Please read the corresponding chapter before attending this lecture. ² These notes are not intended to be complete. They are supplemented with figures, and material that arises during the lecture period in response to questions. ¤Based on Theory of Computing, 2nd Ed., D. Cohen, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1 Closure Properties Theorem: CFLs are closed under union If L1 and L2 are CFLs, then L1 [ L2 is a CFL. Proof 1. Let L1 and L2 be generated by the CFG, G1 = (V1;T1;P1;S1) and G2 = (V2;T2;P2;S2), respectively. 2. Without loss of generality, subscript each nonterminal of G1 with a 1, and each nonterminal of G2 with a 2 (so that V1 \ V2 = ;). 3. Define the CFG, G, that generates L1 [ L2 as follows: G = (V1 [ V2 [ fSg;T1 [ T2;P1 [ P2 [ fS ! S1 j S2g;S). 2 4. A derivation starts with either S ) S1 or S ) S2. 5. Subsequent steps use productions entirely from G1 or entirely from G2. 6. Each word generated thus is either a word in L1 or a word in L2. 3 Example ² Let L1 be PALINDROME, defined by: S ! aSa j bSb j a j b j Λ n n ² Let L2 be fa b jn ¸ 0g defined by: S ! aSb j Λ ² Then the union language is defined by: S ! S1 j S2 S1 ! aS1a j bS1b j a j b j Λ S2 ! aS2b j Λ 4 Theorem: CFLs are closed under concatenation If L1 and L2 are CFLs, then L1L2 is a CFL. -

Formal Languages We’Ll Use the English Language As a Running Example

Formal Languages We’ll use the English language as a running example. Definitions. Examples. A string is a finite set of symbols, where • each symbol belongs to an alphabet de- noted by Σ. The set of all strings that can be constructed • from an alphabet Σ is Σ ∗. If x, y are two strings of lengths x and y , • then: | | | | – xy or x y is the concatenation of x and y, so the◦ length, xy = x + y | | | | | | – (x)R is the reversal of x – the kth-power of x is k ! if k =0 x = k 1 x − x, if k>0 ! ◦ – equal, substring, prefix, suffix are de- fined in the expected ways. – Note that the language is not the same language as !. ∅ 73 Operations on Languages Suppose that LE is the English language and that LF is the French language over an alphabet Σ. Complementation: L = Σ L • ∗ − LE is the set of all words that do NOT belong in the english dictionary . Union: L1 L2 = x : x L1 or x L2 • ∪ { ∈ ∈ } L L is the set of all english and french words. E ∪ F Intersection: L1 L2 = x : x L1 and x L2 • ∩ { ∈ ∈ } LE LF is the set of all words that belong to both english and∩ french...eg., journal Concatenation: L1 L2 is the set of all strings xy such • ◦ that x L1 and y L2 ∈ ∈ Q: What is an example of a string in L L ? E ◦ F goodnuit Q: What if L or L is ? What is L L ? E F ∅ E ◦ F ∅ 74 Kleene star: L∗. -

Finite-State Automata and Algorithms

Finite-State Automata and Algorithms Bernd Kiefer, [email protected] Many thanks to Anette Frank for the slides MSc. Computational Linguistics Course, SS 2009 Overview . Finite-state automata (FSA) – What for? – Recap: Chomsky hierarchy of grammars and languages – FSA, regular languages and regular expressions – Appropriate problem classes and applications . Finite-state automata and algorithms – Regular expressions and FSA – Deterministic (DFSA) vs. non-deterministic (NFSA) finite-state automata – Determinization: from NFSA to DFSA – Minimization of DFSA . Extensions: finite-state transducers and FST operations Finite-state automata: What for? Chomsky Hierarchy of Hierarchy of Grammars and Languages Automata . Regular languages . Regular PS grammar (Type-3) Finite-state automata . Context-free languages . Context-free PS grammar (Type-2) Push-down automata . Context-sensitive languages . Tree adjoining grammars (Type-1) Linear bounded automata . Type-0 languages . General PS grammars Turing machine computationally more complex less efficient Finite-state automata model regular languages Regular describe/specify expressions describe/specify Finite describe/specify Regular automata recognize languages executable! Finite-state MACHINE Finite-state automata model regular languages Regular describe/specify expressions describe/specify Regular Finite describe/specify Regular grammars automata recognize/generate languages executable! executable! • properties of regular languages • appropriate problem classes Finite-state • algorithms for FSA MACHINE Languages, formal languages and grammars . Alphabet Σ : finite set of symbols Σ . String : sequence x1 ... xn of symbols xi from the alphabet – Special case: empty string ε . Language over Σ : the set of strings that can be generated from Σ – Sigma star Σ* : set of all possible strings over the alphabet Σ Σ = {a, b} Σ* = {ε, a, b, aa, ab, ba, bb, aaa, aab, ...} – Sigma plus Σ+ : Σ+ = Σ* -{ε} Strings – Special languages: ∅ = {} (empty language) ≠ {ε} (language of empty string) . -

Using Jflap in Academics to Understand Automata Theory in a Better Way

International Journal of Advances in Electronics and Computer Science, ISSN: 2393-2835 Volume-5, Issue-5, May.-2018 http://iraj.in USING JFLAP IN ACADEMICS TO UNDERSTAND AUTOMATA THEORY IN A BETTER WAY KAVITA TEWANI Assistant Professor, Institute of Technology, Nirma University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - As it is been observed that the things get much easier once we visualize it and hence this paper is just a step towards it. Usually many subjects in computer engineering curriculum like algorithms, data structures, and theory of computation are taught theoretically however it lacks the visualization that may help students to understand the concepts in a better way. The paper shows some of the practices on tool called JFLAP (Java Formal Languages and Automata Package) and the statistics on how it affected the students to learn the concepts easily. The diagrammatic representation is used to help the theory mentioned. Keywords - Automata, JFLAP, Grammar, Chomsky Heirarchy , Turing Machine, DFA, NFA I. INTRODUCTION visualization and interaction in the course is enhanced through the popular software tools[6,7]. The proper The theory of computation is a basic course in use of JFLAP and instructions are provided in the computer engineering discipline. It is the subject manual “JFLAP activities for Formal Languages and which is been taught theoretically and hands-on Automata” by Peter Linz and Susan Rodger. It problems are given to the students to enhance the includes the theoretical approach and their understanding but it lacks the programming implementation in JFLAP. [10] assignment. However the subject is the base for creation of compilers and therefore should be given III. -

Chapter 3: Lexing and Parsing

Chapter 3: Lexing and Parsing Aarne Ranta Slides for the book "Implementing Programming Languages. An Introduction to Compilers and Interpreters", College Publications, 2012. Lexing and Parsing* Deeper understanding of the previous chapter Regular expressions and finite automata • the compilation procedure • why automata may explode in size • why parentheses cannot be matched by finite automata Context-free grammars and parsing algorithms. • LL and LR parsing • why context-free grammars cannot alone specify languages • why conflicts arise The standard tools The code generated by BNFC is processed by other tools: • Lex (Alex for Haskell, JLex for Java, Flex for C) • Yacc (Happy for Haskell, Cup for Java, Bison for C) Lex and YACC are the original tools from the early 1970's. They are based on the theory of formal languages: • Lex code is regular expressions, converted to finite automata. • Yacc code is context-free grammars, converted to LALR(1) parsers. The theory of formal languages A formal language is, mathematically, just any set of sequences of symbols, Symbols are just elements from any finite set, such as the 128 7-bit ASCII characters. Programming languages are examples of formal languages. In the theory, usually simpler languages are studied. But the complexity of real languages is mostly due to repetitions of simple well-known patterns. Regular languages A regular language is, like any formal language, a set of strings, i.e. sequences of symbols, from a finite set of symbols called the alphabet. All regular languages can be defined by regular expressions in the following set: expression language 'a' fag AB fabja 2 [[A]]; b 2 [[B]]g A j B [[A]] [ [[B]] A* fa1a2 : : : anjai 2 [[A]]; n ≥ 0g eps fg (empty string) [[A]] is the set corresponding to the expression A.