Rapid Review of DFID's Humanitarian Response to Typhoon Haiyan in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fy 2014 Brgy

CY 2014 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT FOR BARANGAYS PROVINCE OF ILOILO (In P0.00 ) COMPUTATION OF THE FY 2013 FINAL INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT CY 2010 Census of P80,000 BARANGAY Population FOR BRGYS. SHARE EQUAL TOTAL W/ 100 OR MORE BASED ON SHARING (ROUNDED) POPULATION POPULATION MUNICIPALITY OF AJUY 1 Adcadarao 595 80,000.00 248,123.73 607,973.12 936,097.00 2 Agbobolo 288 80,000.00 120,100.23 607,973.12 808,073.00 3 Badiangan 1,086 80,000.00 452,877.94 607,973.12 1,140,851.00 4 Barrido 1,536 80,000.00 640,534.55 607,973.12 1,328,508.00 5 Bato Biasong 941 80,000.00 392,410.81 607,973.12 1,080,384.00 6 Bay-ang 2,622 80,000.00 1,093,412.49 607,973.12 1,781,386.00 7 Bucana Bunglas 348 80,000.00 145,121.11 607,973.12 833,094.00 8 Central 1,788 80,000.00 745,622.25 607,973.12 1,433,595.00 9 Culasi 4,401 80,000.00 1,835,281.60 607,973.12 2,523,255.00 10 Lanjagan 1,166 80,000.00 486,239.12 607,973.12 1,174,212.00 11 Luca 3,131 80,000.00 1,305,672.96 607,973.12 1,993,646.00 12 Malayu-an 2,790 80,000.00 1,163,470.95 607,973.12 1,851,444.00 13 Mangorocoro 1,142 80,000.00 476,230.76 607,973.12 1,164,204.00 14 Nasidman 490 80,000.00 204,337.19 607,973.12 892,310.00 15 Pantalan Nabaye 1,125 80,000.00 469,141.51 607,973.12 1,157,115.00 16 Pantalan Navarro 453 80,000.00 188,907.65 607,973.12 876,881.00 17 Pedada 1,265 80,000.00 527,523.57 607,973.12 1,215,497.00 18 Pili 2,606 80,000.00 1,086,740.25 607,973.12 1,774,713.00 19 Pinantan Diel 507 80,000.00 211,426.44 607,973.12 899,400.00 20 Pinantan Elizalde 531 80,000.00 221,434.79 607,973.12 909,408.00 -

Marine Accidents from 72 to Presentorigfinal Docx

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Department of Transportation and Communications PUNONGHIMPILAN TANOD BAYBAYIN NG PILIPINAS (HEADQUARTERS PHILIPPINE COAST GUARD ) BOARD OF MARINE INQUIRY TH 139 25 STREET , PORT AREA , MANILA MARINE ACCIDENTS FROM 1972-PRESENT NO. VESSEL’s CASE NO. & PLACE OF DATE OF BMI NO. OF SURVI- BMI & SBMI DATE NAME NATURE INCIDENT INCIDENT F & R CASUALTIES VOR FINDINGS FORWARDED TO (dated) DEAD/MISSIN AND LEGAL G RECOMMENDATION S 450 M/V Baleno SBMI Off Isla Verde, 26 Dec 09 6 Dead 73 Owner/shipmaster & Officer Owner/shipmaster 9 Capsizing Batangas 44 Survivors violate PPA Administrative & Officer violate Order No. 03-2006 on Guidelines Implementing PPA Missing VTMS, violate Memo Cir N0 Administrative 170, Human error. Order No. 03-2006 on Guidelines Implementing VTMS, violate Memo Cir N0 170, Human error. 449 M/V Catalyn SBMI 3 NM from 24 Dec 09 10 Dead B Collision Limbones 17 46 Ongoing Investigation VS. Island off Survivors F/V Anatalia Maragondon, Missing Cavite 448 M/V SBMI-03-06 At the vicinity in bet 11 Mar 06 Human error For review Premship X Collision/ the sec to the last red buoy and last Vs. Sinking red buoy, Tagud M/V Mihara II Consolascion side. 447 M/V Super BMI-942-09 Coastal waters off 06 Sept 2009 20 Nov 09 10 Dead 958 Human error Forwarded to CPCG Ferry 9 Capsizing/Sinking Zamboanga Survivors Decision dtd Dec 07, 2009 (ATSC) Peninsula 1 446 M/Bca SBMI-001-09 Vicinity waters of 231300H May 7 Jul 09 43 Human error Forwarded to CPCG Commandos-6 Capsizing Malahibomanok, 2009 12 Dead Survivors Decision dtd Batangas Bay, Oct 28, 2009 Batangas City 445 M/Bca Mae SBMI-01-08 Vicinity of Linao, 14 Dec 08 23 Mar 09 47 30 45 The proximate and Forwarded to CPCG Jan Capsizing Aparri, Cagayan Dead Survivors immediate cause of Decision dtd capsizing is the breaking of Nov. -

Weekly Edition 16 of 2020

Notices 1922 -- 2047/20 ADMIRALTY NOTICES TO MARINERS Weekly Edition 16 16 April 2020 (Published on the ADMIRALTY website 06 April 2020) CONTENTS I Explanatory Notes. Publications List II ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners. Updates to Standard Nautical Charts III Reprints of NAVAREA I Navigational Warnings IV Updates to ADMIRALTY Sailing Directions V Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Lights and Fog Signals VI Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Radio Signals VII Updates to Miscellaneous ADMIRALTY Nautical Publications VIII Updates to ADMIRALTY Digital Services For information on how to update your ADMIRALTY products using ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners, please refer to NP294 How to Keep Your ADMIRALTY Products Up--to--Date. Mariners are requested to inform the UKHO immediately of the discovery of new or suspected dangers to navigation, observed changes to navigational aids and of shortcomings in both paper and digital ADMIRALTY Charts or Publications. The H--Note App helps you to send H--Notes to the UKHO, using your device’s camera, GPS and email. It is available for free download on Google Play and on the App Store. The Hydrographic Note Form (H102) should be used to forward this information and to report any ENC display issues. H102A should be used for reporting changes to Port Information. H102B should be used for reporting GPS/Chart Datum observations. Copies of these forms can be found at the back of this bulletin and on the UKHO website. The following communication facilities are available: NMs on ADMIRALTY website: Web: admiralty.co.uk/msi Searchable Notices to Mariners: Web: www.ukho.gov.uk/nmwebsearch Urgent navigational information: e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 353448 +44(0)7989 398345 Fax: +44(0)1823 322352 H102 forms e--mail: [email protected] (see back pages of this Weekly Edition) Post: UKHO, Admiralty Way, Taunton, Somerset, TA1 2DN, UK All other enquiries/information e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 484444 (24/7) Crown Copyright 2020. -

R6 CY 2010 IRA Level Brgy LBM

CY 2010 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT FOR BARANGAYS REGION VI PROVINCE OF ILOILO COMPUTATION OF THE CY 2010 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT CY 2007 Census of P80,000 BARANGAY Population FOR BRGYS. SHARE EQUAL TOTAL W/ 100 OR MORE BASED ON SHARING (ROUNDED) POPULATION POPULATION MUNICIPALITY OF AJUY 1 Adcadarao 504 80,000.00 166,530.62 463,312.44 709,843.00 2 Agbobolo 271 80,000.00 89,543.25 463,312.44 632,856.00 3 Badiangan 1,096 80,000.00 362,138.01 463,312.44 905,450.00 4 Barrido 1,453 80,000.00 480,097.19 463,312.44 1,023,410.00 5 Bato Biasong 923 80,000.00 304,975.71 463,312.44 848,288.00 6 Bay-ang 2,567 80,000.00 848,182.72 463,312.44 1,391,495.00 7 Bucana Bunglas 357 80,000.00 117,959.19 463,312.44 661,272.00 8 Central 1,759 80,000.00 581,205.07 463,312.44 1,124,518.00 9 Culasi 4,292 80,000.00 1,418,153.58 463,312.44 1,961,466.00 10 Lanjagan 1,156 80,000.00 381,963.08 463,312.44 925,276.00 11 Luca 2,831 80,000.00 935,413.04 463,312.44 1,478,725.00 12 Malayu-an 2,797 80,000.00 924,178.84 463,312.44 1,467,491.00 13 Mangorocoro 1,324 80,000.00 437,473.29 463,312.44 980,786.00 14 Nasidman 478 80,000.00 157,939.75 463,312.44 701,252.00 15 Pantalan Nabaye 1,235 80,000.00 408,066.09 463,312.44 951,379.00 16 Pantalan Navarro 436 80,000.00 144,062.20 463,312.44 687,375.00 17 Pedada 1,220 80,000.00 403,109.82 463,312.44 946,422.00 18 Pili 2,600 80,000.00 859,086.51 463,312.44 1,402,399.00 19 Pinantan Diel 419 80,000.00 138,445.10 463,312.44 681,758.00 20 Pinantan Elizalde 534 80,000.00 176,443.15 463,312.44 719,756.00 21 Pinay Espinosa 1,142 80,000.00 -

Postal Code Province City Barangay Amti Bao-Yan Danac East Danac West

Postal Code Province City Barangay Amti Bao-Yan Danac East Danac West 2815 Dao-Angan Boliney Dumagas Kilong-Olao Poblacion (Boliney) Abang Bangbangcag Bangcagan Banglolao Bugbog Calao Dugong Labon Layugan Madalipay North Poblacion 2805 Bucay Pagala Pakiling Palaquio Patoc Quimloong Salnec San Miguel Siblong South Poblacion Tabiog Ducligan Labaan 2817 Bucloc Lamao Lingay Ableg Cabaruyan 2816 Pikek Daguioman Tui Abaquid Cabaruan Caupasan Danglas 2825 Danglas Nagaparan Padangitan Pangal Bayaan Cabaroan Calumbaya Cardona Isit Kimmalaba Libtec Lub-Lubba 2801 Dolores Mudiit Namit-Ingan Pacac Poblacion Salucag Talogtog Taping Benben (Bonbon) Bulbulala Buli Canan (Gapan) Liguis Malabbaga 2826 La Paz Mudeng Pidipid Poblacion San Gregorio Toon Udangan Bacag Buneg Guinguinabang 2821 Lacub Lan-Ag Pacoc Poblacion (Talampac) Aguet Bacooc Balais Cayapa Dalaguisen Laang Lagben Laguiben Nagtipulan 2802 Nagtupacan Lagangilang Paganao Pawa Poblacion Presentar San Isidro Tagodtod Taping Ba-I Collago Pang-Ot 2824 Lagayan Poblacion Pulot Baac Dalayap (Nalaas) Mabungtot 2807 Malapaao Langiden Poblacion Quillat Bonglo (Patagui) Bulbulala Cawayan Domenglay Lenneng Mapisla 2819 Mogao Nalbuan Licuan-Baay (Licuan) Poblacion Subagan Tumalip Ampalioc Barit Gayaman Lul-Luno 2813 Abra Luba Luzong Nagbukel-Tuquipa Poblacion Sabnangan Bayabas Binasaran Buanao Dulao Duldulao Gacab 2820 Lat-Ey Malibcong Malibcong Mataragan Pacgued Taripan Umnap Ayyeng Catacdegan Nuevo Catacdegan Viejo Luzong San Jose Norte San Jose Sur 2810 Manabo San Juan Norte San Juan Sur San Ramon East -

Aklan Antique Capiz Guimaras Iloilo Masbate Negros Occidental Negros

121°50'E 122°0'E 122°10'E 122°20'E 122°30'E 122°40'E 122°50'E 123°0'E 123°10'E 123°20'E Busay Tonga Salvacion Panubigan Panguiranan Lanas Poblacion Mapitogo Romblon Palane Mapili Pinamihagan Poblacion Jangan Ilaya Victory Masbate Dao Balud Baybay Sampad 12°0'N 12°0'N Yapak Ubo San Balabag Antonio San Andres Quinayangan Diotay Quinayangan Tonga Manoc-Manoc Guinbanwahan Mabuhay Bongcanaway Danao Union Pulanduta Caticlan Argao Rizal Calumpang Cubay San Norte Viray Unidos Poblacion Cogon Pawa Naasug Motag Balusbus Cubay Libertad Dumlog Sur Malay Bel-Is Cabulihan Nabaoy Tagororoc Mayapay Napaan Habana Habana Balusbos Jintotolo Cabugan Gibon Alegria Laserna Toledo Cantil Poblacion El Progreso Tag-Osip Nabas Nagustan Buruanga Poblacion Katipunan Buenasuerte Nazareth Alimbo-Baybay 11°50'N Buenavista Aslum 11°50'N Buenafortuna Ondoy Poblacion Colongcolong Aquino Agbago Polo San Tigum Inyawan Solido Tagbaya Isidro Matabana Tul-Ang Bugtongbato Maramig Magallanes Laguinbanua Buenavista Naisud Panilongan Pajo Santa Bagacay Cubay Luhod-Bayang Antipolo Cruz Jawili Libertad Pinatuad Capilijan Panangkilon Batuan Afga Santander San Rizal Codiong Unat Regador Paz Roque Mabusao Dumatad Poblacion Tinindugan Igcagay Candari Maloco Naligusan Bagongbayan Centro Santa Weste Baybay Lindero Barusbus Bulanao Cruz Buang Agdugayan Panayakan Tagas Union Pucio Taboc Tondog Dapdap Tinigbas San Naile Tangalan Sapatos Patria Santo Guia Joaquin Fragante Cabugao Tamalagon Baybay Duyong Rosario Zaldivar Jinalinan Santa Tingib Cabugao Pudiot Nauring Ana Lanipga Dumga Alibagon -

This Keyword List Contains Pacific Ocean (Excluding Great Barrier Reef)

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 3/2/2016 Pacific Ocean (without the Great Barrier Reef) This keyword list contains Pacific Ocean (excluding Great Barrier Reef) place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Pacific Ocean (without Great Barrier Reef)” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Cauit Reefs (13N123E0016) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Legaspi (13N123E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Manito Reef (13N123E0015) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Matalibong ( Bariis ) (13N123E0006) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Rapu Rapu Island (13N124E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Sto. Domingo (13N123E0002) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amalau Bay (14S170E0012) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amami-Gunto > Amami-Gunto (28N129E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > American Samoa (14S170W0000) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > Manu'a Islands (14S170W0038) OCEAN BASIN > -

DRR Activities -Matrix 12082014 V3

PHILIPPINES: Summary of DRR Activities in Region VI (Western Visayas) (as of 11 August 2014) PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY ORGANISATION PROJECT TITLE Camanci Lupit Mambuquaio World Vision PFA (Psychological First Aid) Batan Man‐up Tabon Not Specified CARE DRR Polocate Agbanawan Badiangan San Isidro Venturanza AKLAN Sigcay Banga Mambog ADRA Support Self Recovery Shelter– Aklan Muguing Linabuan Sur Jumarap Palale Cerrudo Pasanghan Malinao Not Specified New Washington Not Specified CARE DRR Barbaza Not Specified CARE DRR Batbatan Island Philippine Red Cross (PRC)/German Red Cross Culasi Malalison Island (GRC) PRC/GRC Haiyan Recovery Antique Laua‐an Not Specified CARE DRR Barangay 4 (Pob) Bariri San Jose Bugarot PRC/GRC Haiyan Recovery Antique Durog Philippine Red Cross (PRC)/German Red Cross Maybato Sur (GRC) Alegre ANTIQUE Esparagoza Importante Martinez Philippine Red Cross (PRC)/German Red Cross Tibiao PRC/GRC Haiyan Recovery Antique Natividad (GRC) San Francisco Norte San Isidro Tigbaboy CAPIZ Cuartero Mahabang Sapa IOM Disaster Preparedness Orientation PHILIPPINES: Summary of DRR Activities in Region VI (Western Visayas) (as of 11 August 2014) PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY ORGANISATION PROJECT TITLE San Martin San Miguel Philippine Red Cross (PRC)/German Red Cross Dumalag San Rafael PRC/GRC Haiyan Recovery Capiz (GRC) Sto. Angel Sto. Nino Aglalana IOM Disaster Preparedness Orientation Aglanot Agsirab Dumarao Lawaan PRC/GRC Haiyan Recovery Capiz Sagrada Familia Philippine Red Cross (PRC)/German Red Cross Tina (GRC) Agmalobo Bridging -

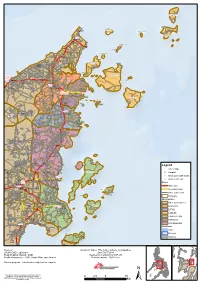

Iloilo Guimaras

REGION VI (Western Visayas) Humanitarian Organizations activities in Iloilo province (as of 22 Dec) 122°27'30"E 122°58'0"E N " Number of total activities 0 Ongoing Activities 3 ' 0 Organizations 1 ° 2 No Data 1 Action contre la Faim 1 <30 Mandaon DSWD 1 30-100 Humanity Purse 2 <100 IOM 28 Médecins Sans Frontières 4 Save the Children 1 UNICEF 1 World Vision International 1 Organizations DOLE 18 UNDP 16 Organizations GIZ 77 International Rescue Committee 8 Nabas IOM 1 Save the Children 164 UNICEF 8 Ibajay Welthungerhilfe 22 Pandan Tangalan World Vision International 4 Numancia Organizations Makato ADRA 4 N " Kalibo 0 ' Caritas 1 0 4 Lezo ° 1 Citizens' Disaster Response Cente6r 1 New Washington Concern Worldwide 76 Banga Malinao DfID 3 DfiD 3 Nabunot Island Disaster Aid International 2 Roxas City Batan Carles Handicap International 6 Sebaste Balete Panay Tumaquin Island Humanity First 5 AKLAN Ivisan Binuluangan Island Sapi-An International Rescue Committee 34 Altavas Calagnan IsIOlaMnd 5 Madalag Balasan Pilar Médecins Sans Frontières 45 Panitan Estancia Sicogon Island Mambusao Sigma Philippine Red Cross 7 Culasi Libacao President Roxas Bayas Island Batad Relief operation for Northern Iloilo 2 Dao Save the Children 109 Jamindan Solidar Suisse 16 CAPIZ Ma-Ayon UNFPA 1 San Dionisio World Vision International 8 Tibiao Dumalag Cuartero Sara Organizations Sambrero Island Action contre la Faim 8 Barbaza Tapaz Dumarao ADRA 6 CARE 15 Lemery Caritas 12 Bingawan Concepcion Igbon Island N " Center for Agrarian Reform and Rur9a0l Development 0 3 Passi ' 9 ° Laua-An San Rafael Christian Aid 100 1 Calinog City 1 Ajuy Concern 12 Lambunao San Tagubanhan Island DSWD 45 Enrique FAO 12 Barotac Viejo GOAL 7 Bugasong Duenas Banate HEKS 1 Valderrama Badiangan Dingle International Rescue Committee 8 Janiuay Anilao Médecins Sans Frontières 92 ILOILO Save the Children 53 WFP 80 Mina Pototan World Vision International 11 Patnongon Maasin Manapla San Remigio Barotac Nuevo Organizations Cabatuan New Enrique Victorias Access Aid international 13 Alimodian Lucena B. -

Legend 0 5 10 2.5 Km

ASLUMAN Granada(!G! Granada Granada BHS Isla Gigante Norte GRANADA Gabi Gabi BHS G! (!Gabi Nabunut Island Cabugwana GABI Cabuquana ! Cabuguana BUENAVISTA Balbagon Island !Lantangan LANTANGAN PUNTA (BOLOCAWE) LANTANGAN Isla Gigante Sur Carles RHU G Carles !(Carles CABUGUANA LANTANGAN POBLACION LANTANGAN Cabilao Grande! Cabilao Kabilao Grande BAROSBOS BANCAL Tulunananum Island LANTANGAN Bankal(!G! Bancal Bancal BUENAVISTA Barosbos Bancal BHS Barrosbos ! Barrosbos GUINTICGAN Buenavista CABILAO Buenavista ! Dayhagan Guinticgan GRANDE Dayhagan ! ! Guinticgan DAYHAGAN C!abilao Abong Abong (!G! Kabilao Abong Tabugon Island Cawayan BHS ABONG BHS CauayanG! Cawayan TABUGON ! (! CABILAO ! Pinanlabuan Cawayan Pinanlabuan PEQUE-O ! Tarong DAYHAGAN TarongG! (! Tabugun CAWAYAN ! ISLA Tarong Tabugun DE CANA BHS TABUGON (!G Balogo BHS Binuluangan Island ! BALOGO TARONG Tinigban Balogo ! BOLO BINULUANGAN BHS !Casanayan G! Balogo (!Binuluangan (!G! CASANAYAN Casanayan Tupas Binulwangan Bolo ! SAN Bolo ! Tupas ! BHS Taytay ANTONIO Taytay ! G (! TUPAZ ! Casanayan TINIGBAN ! BHS PANTALAN TUPAZ NATIVIDAD SAN RAMON NALUMSAN Manjogay Mambot Pantalan Apad ! Manjogay Nalumsan Mambot ! Pantalan ! Apad ! Nalumsan(!G! Sta Fe G Manlot Island (! Nalumsan Mamhut SAN MANLOT Calangnaan Island ! BHS PEDRO BHS Norte San Pedro BHS Manhut ! MANLOT Santa Fe SAN !G Mamhut Norte Pilar Medicare & ! ESTEBAN ( Manhut Santa Fe BALANTI-AN MAMHUT Commmunity BARANGCALAN NORTE BARANGCALAN Poblacion BHS KINALKALAN LAWIS HospGital G Kinalkalan Balanti-an BHS (! POBLACIO(!N Natividad Kinalkalan -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AKLAN 535,725 ALTAVAS 23,919 Cabangila 1,705 Cabugao 1,708 Catmon

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aklan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AKLAN 535,725 ALTAVAS 23,919 Cabangila 1,705 Cabugao 1,708 Catmon 1,504 Dalipdip 698 Ginictan 1,527 Linayasan 1,860 Lumaynay 1,585 Lupo 2,251 Man-up 2,360 Odiong 2,961 Poblacion 2,465 Quinasay-an 459 Talon 1,587 Tibiao 1,249 BALETE 27,197 Aranas 5,083 Arcangel 3,454 Calizo 3,773 Cortes 2,872 Feliciano 2,788 Fulgencio 3,230 Guanko 1,322 Morales 2,619 Oquendo 1,226 Poblacion 830 BANGA 38,063 Agbanawan 1,458 Bacan 1,637 Badiangan 1,644 Cerrudo 1,237 Cupang 736 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aklan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Daguitan 477 Daja Norte 1,563 Daja Sur 602 Dingle 723 Jumarap 1,744 Lapnag 594 Libas 1,662 Linabuan Sur 3,455 Mambog 1,596 Mangan 1,632 Muguing 695 Pagsanghan 1,735 Palale 599 Poblacion 2,469 Polo 1,240 Polocate 1,638 San Isidro 305 Sibalew 940 Sigcay 974 Taba-ao 1,196 Tabayon 1,454 Tinapuay 381 Torralba 1,550 Ugsod 1,426 Venturanza 701 BATAN 30,312 Ambolong 2,047 Angas 1,456 Bay-ang 2,096 Caiyang 832 Cabugao 1,948 Camaligan 2,616 Camanci 2,544 Ipil 504 Lalab 2,820 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aklan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Lupit 1,593 Magpag-ong -

Legend Lantangan SCI Early Recovery & Livelihoods FAO Bancal Food Security and Agriculture Carles

Region VI (Western Visayas) : Food Security and Agriculture And Early Recovery & Livelihoods Clusters Ongoing Response Activities in ILOILO Province (a s of 23 May 2014) 123°0'0"E CARLES Concern Worldwide Carles Gabi Punta SCI Legend Lantangan SCI Early Recovery & Livelihoods FAO Bancal Food Security and Agriculture Carles Abong Organisations Acronyms Tabugon Cawayan NAA-NCCP ACT Alliance Binuluangan SOS Save Our Species Tarong TFB-Task Force Buliganay BALASAN Pantalan Tinigban Data Source: ACF Manlot OCHA, DSWD, GADM Barangcalan Gogo 01.75 3.5 7 San Roque Daculan Talingting Carles Km Poblacion Norte ¯ Bayuyan Tacbuyan Punta Batuanan philippines.humanitarianresponse.info Loguingot Bito-On Feedback: [email protected] Created 27 May 2014 Balasan Cano-An Pa-On BATAD Daan Banua Estancia Botongan Manipulon Tanza SCI Santa Ana ESTANCIA Bayas KAISA Fdt. Jolog NAA SCI Embarcadero SOS Salong TFB Batad Banban WVI Alinsolong Binon-An ACF Tanao SCI Madanlog Odiongan World Renew Capiz Tamangi Mandu-Awak Agdaliran Bagacay Boroñgon Cubay SAN DIONISIO Hacienda Conchita San Dionisio SCI Cudionan KAISA Fdt. Sua San Nicolas ACF Sara Tuble Tiabas FAO Capinang Dugman SCI Pase Santol Bondulan Siempreviva Malangabang Bacjawan Norte CONCEPCION CALINOG Lemery Bacjawan Sur ACF Igbon Concern Worldwide Poblacion One Meal World Renew Polopina Pantalan Navarro SCI Bingawan Lo-Ong Lanjagan FAO Niño SCI Taguhangin Rojas Plandico Nipa Concepcion Passi City Ajuy Pantalan Nabaye Bucana Bunglas AJUY Silagon San Rafael Bato Biasong Maliogliog ADRA Mangorocoro Calinog Concern Worldwide Bagongon KAISA Fdt. Tagubanhan Canabajan ADRA Pili FAO Punta Buri San Enrique Malayu-An Santo Rosario Barrido Culasi Luca Barotac Viejo Nasidman Duenas Banate Pedada Dingle Bay-Ang Badiangan Anilao.