Analysis of United States Compassionate and Geriatric Release Laws: Towards a Rights-Based Response for Diverse Elders and Their Families and Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aging in Prison a Human Rights Problem We Must Fix

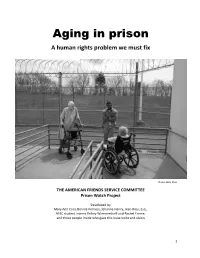

Aging in prison A human rights problem we must fix Photo: Nikki Khan THE AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Prison Watch Project Developed by Mary Ann Cool, Bonnie Kerness, Jehanne Henry, Jean Ross, Esq., AFSC student interns Kelsey Wimmershoff and Rachel Frome, and those people inside who gave this issue voice and vision 1 Table of contents 1. Overview 3 2. Testimonials 6 3. Preliminary recommendations for New Jersey 11 4. Acknowledgements 13 2 Overview The population of elderly prisoners is on the rise The number and percentage of elderly prisoners in the United States has grown dramatically in past decades. In the year 2000, prisoners age 55 and older accounted for 3 percent of the prison population. Today, they are about 16 percent of that population. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of prisoners age 65 and older increased by an alarming 63 percent, compared to a 0.7 percent increase of the overall prison population. At this rate, prisoners 55 and older will approach one-third of the total prison population by the year 2030.1 What accounts for this rise in the number of elderly prisoners? The rise in the number of older people in prisons does not reflect an increased crime rate among this population. Rather, the driving force for this phenomenon has been the “tough on crime” policies adopted throughout the prison system, from sentencing through parole. In recent decades, state and federal legislators have increased the lengths of sentences through mandatory minimums and three- strikes laws, increased the number of crimes punished with life and life-without-parole and made some crimes ineligible for parole. -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

Aging of the State Prison Population, 1993–2013 E

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics MAY 2016 Special Report NCJ 248766 Aging of the State Prison Population, 1993–2013 E. Ann Carson, Ph.D., BJS Statistician, and William J. Sabol, Ph.D., former BJS Director he number of prisoners sentenced to more than FIGURE 1 1 year under the jurisdiction of state correctional Sentenced state prisoners, by age, December 31, 1993, 2003, authorities increased 55% over the past two decades, and 2013 Tfrom 857,700 in 1993 to 1,325,300 in 2013. During the same period, the number of state prisoners age 55 or older Sentenced state prisoners increased 400%, from 3% of the total state prison population 1,000,000 in 1993 to 10% in 2013 (figure 1). Between 1993 and 2003, 800,000 the majority of the growth occurred among prisoners 39 or younger ages 40 to 54, while the number of those age 55 or older 600,000 increased faster from 2003 to 2013. In 1993, the median age 40–54 of prisoners was 30; by 2013, the median age was 36. The 400,000 changing age structure in the U.S. state prison population 200,000 has implications for the future management and care 55 or older of inmates. 0 1993 2003 2013 Two factors contributed to the aging of state prisoners Year between 1993 and 2013: (1) a greater proportion of Note: Based on prisoners sentenced to more than 1 year under the jurisdiction prisoners were sentenced to, and serving longer periods of state correctional authorities. -

Older Men in Prison : Emotional, Social, and Physical Health Characteristics

OLDER MEN IN PRISON: EMOTIONAL, SOCIALl AND PHYSICAL HEALTH CHARACTERISTICS Elaine Marie Gallagher B.Sc.N., University of Windsor, 196' M.Sc., Duke University, 1976 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Special Arrangements @~laine Marie Gallagher SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY March, 1988 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Elaine Marie Gallagher Degree: .?h. D. Interdisciplinary Studies Title of thesis: Emotional, Social and Physical Health Needs of Older Men in Prison. Examining Committee: Chairman: Dr. Bruce Clayman Dean of Graduate Studies Senior Supervisor: Dr. Gloria Gutman , -,,r LC.- Director Gerontology Center and Program Dr. Ellen Gee . ., Assistant Professor, Sociology Dr. Margaret Jackson I - Assistant Professor, Criminology External Examiners Dr. Real Prefontaine _- J Director, Treatment Services and Regional Health Care, Correctional Services of Canada Dr. Cathleen Burnett - - P.ssistant Professor, Sociology - P.dministration of Justice Program, University of Missouri-Kansas City PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser Unlverslty the right to lend my thesis, proJect or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or In response to a request from the I ibrary of any other university, or other educatlonal institution, on its own behalf or for one of Its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

When Prison Gets Old: Examining New Challenges Facing Elderly Prisoners in America

When Prison Gets Old: Examining New Challenges Facing Elderly Prisoners In America by Benjamin Pomerance ―The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” -- Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky John H. Bunz will celebrate his ninety-second birthday in November.1 Described by observers as ―feeble-looking‖ after the death of his wife in 2010, he requires a walker to take even a couple of steps, and needs a wheelchair to travel any distance of significant length.2 Yet he still is in better health than George Sanges, age 73, who suffers from cerebral palsy, has sagging skin that is listed as ―sallow,‖ takes multiple medications twice a day, and has recently been rushed to the emergency room for heart problems.3 And both of them are far more alert than Leon Baham, a 71-year-old man who has dementia and goes into delusional bouts of yearning for the company of his now-dead wife.4 On the surface, all of these elderly, ailing men have extremely sympathetic profiles. All three need intensive medical care.5 All three have unique physical and emotional needs that are inherent to growing older.6 All three appear to be the type of ―grandfatherly‖ figures to whom our society is historically taught to show the utmost compassion and concern. Yet all three of these individuals also have a huge component of their lives which would naturally tend to turn all thoughts of sympathy and care upside-down. They are all prisoners.7 Not low-level criminals, either, but violent felony offenders with significant sentences. -

Aging Behind Bars: Trends and Implications of Graying Prisoners In

Aging Behind Bars Trends and Implications of Graying Prisoners in the Federal Prison System KiDeuk Kim Bryce Peterson August 2014 Acknowledgments This report was prepared with intramural support from the Urban Institute. The authors would also like to acknowledge the insightful advice and support from Laurie Robinson of George Mason University, and Julie Samuels and Miriam Becker-Cohen of the Urban Institute. Any remaining errors are the authors’ alone. About the Authors KiDeuk Kim is a senior research associate in the Justice Police Center of the Urban Institute and a visiting fellow at the Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. His current research focuses on policy evaluation in criminal justice. Bryce Peterson is a research associate in the Justice Police Center of the Urban Institute. His current research interests include various issues related to correctional populations and their families. Copyright © August 2014. Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. Cover photograph © 2013. Yahoo News/Getty Image. The nonprofit Urban Institute is dedicated to elevating the debate on social and economic policy. For nearly five decades, Urban scholars have conducted research and offered evidence-based solutions that improve lives and strengthen communities across a rapidly urbanizing world. Their objective research helps expand opportunities for all, reduce hardship among the most vulnerable, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector. The views expressed -

It's About Time

CENTER ON SENTENCING AND CORRECTIONS Tina Chiu A and GeriatricRelease Increasing Costs, Aging Prisoners, Time About It’s PR I L 2010 istockphoto.com/mrrabbit2502 Executive Summary As harsher policies have led to longer prison sentences, often with a limited possibility of parole, correctional facilities throughout the United States are home to a growing number of elderly adults. Because this population has extensive and costly medical needs, states are con- fronting the complex, expensive repercussions of their sentencing practices. To reduce the costs of caring for aging inmates—or to avert future costs—legislators and policymakers have been increasingly will- ing to consider early release for those older prisoners who are seen as posing a relatively low risk to public safety. This report is based upon a statutory review of geriatric release provi- sions, including some medical release practices that specifically refer to elderly inmates. The review was supplemented by interviews and examination of data in publicly available documents. At the end of 2009, 15 states and the District of Columbia had provi- sions for geriatric release. However, the jurisdictions are rarely using these provisions. Four factors help explain the difference between the stated intent and the actual impact of geriatric release laws: political considerations and public opinion; narrow eligibility criteria; proce- dures that discourage inmates from applying for release; and compli- cated and lengthy referral and review processes. This report offers recommendations for responding to the disparities between geriatric release policies and practice, including the following: > States that look to geriatric release as a cost-saving measure must examine how they put policy into practice. -

The Forgotten Victims: Childhood and the Soviet Gulag, 1929–1953

Number 2203 ISSN: 2163-839X (online) Elaine MacKinnon The Forgotten Victims: Childhood and the Soviet Gulag, 1929–1953 This work is licensed under a CreaƟ ve Commons AƩ ribuƟ on-Noncommercial-No DerivaƟ ve Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of PiƩ sburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is cosponsored by the University of PiƩ sburgh Press. Elaine MacKinnon Abstract This study examines a facet of Gulag history that only in recent years has become a topic for scholarly examination, the experiences of children whose par- ents were arrested or who ended up themselves in the camps. It fi rst considers the situation of those who were true “children of the Gulag,” born either in prison or in the camps. Second, the paper examines the children who were left behind when their parents and relatives were arrested in the Stalinist terror of the 1930s. Those left behind without anyone willing or able to take them in ended up in orphanages, or found themselves on their own, having to grow up quickly and cope with adult situations and responsibilities. Thirdly, the study focuses on young persons who themselves ended up in the Gulag, either due to their connections with arrested family members, or due to actions in their own right which fell afoul of Stalinist “legality,” and consider the ways in which their youth shaped their experience of the Gulag and their strategies for survival. The effects of a Gulag childhood were profound both for individuals and for Soviet society as a whole. -

A Demographic Analysis of the North Carolina Prison Population

Aging in Place in the Big House: A Demographic Analysis of the North Carolina Prison Population Frank R. Baumgartner1 Sydney Johnson2 October 11, 2020 Introduction As in other states, North Carolina increased the severity of punishment for many crimes in the 1990s. Sentencing reforms effective in 1994 eliminated the traditional concept of parole from the state’s prison system and enhanced the length of punishment for the most serious crimes. The felony punishment chart laid out in the “structured sentencing” system enacted in 1993 provides for the punishment of LWOP sentences for all level A felonies as well as B1 felonies committed by those with significant numbers of prior points, and a decision by the judge to assign the “aggravated” sentence in the case. Level A felonies are limited to first-degree murder, which may also carry the sentence of death; LWOP here is the lesser sentence. Level B1 crimes include second-degree murder and 18 other crimes, mostly rape and sexual offenses3 (see NC Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission 2014). One obvious consequence of a reform that increases the number of individuals serving prison terms that provide no opportunity of parole is that they will “age in place” within the prison system until they die. Since these reforms were effective in 1994, as of 2020 we have had 1 Richard J. Richardson Distinguished Professor of Political Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, [email protected], corresponding author. 2 2020 Graduate, UNC-Chapel Hill, Political Science. 3 The list also includes terrorist killings with chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons, but no one listed in the NC DPS database is associated with this crime. -

Gulag Vs. Laogai

GULAG VS. LAOGAI THE FUNCTION OF FORCED LABOUR CAMPS IN THE SOVIET UNION AND CHINA Sanne Deckwitz (3443639) MA International Relations in Historical Perspective Utrecht University Supervisor: Prof. dr. B.G.J. de Graaff Second Reader: Dr. L. van de Grift January 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations and Acronyms.................................................................................................. ii Maps…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… iii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Chapter 1: Historical overview of the gulag…………………………………………………………... 6 1.1 Origins of the gulag, 1918-1929…………………………………………………………… 6 1.2 Stalin’s gulag, 1929-1953…………………………………………………………………….. 9 1.3 The gulag after Stalin, 1953-1992………………………………………………………… 14 Chapter 2: Historical overview of the laogai………………………………………………………….. 17 2.1 Origins of the laogai, 1927-1949…………………………………………………………... 18 2.2 The laogai during the Mao Era, 1949-1976…………………………………………… 20 2.3 The laogai after Mao, 1976-present……………………………………………………… 26 Chapter 3: The political function of the gulag and the laogai………………………………….. 29 3.1 Rule by the vanguard party of the proletariat……………………………………….. 29 3.2 Classicide: eliminating external enemies………………………………………………. 32 3.3 Fracticide: eliminating internal enemies………………………………………………. 34 3.4 China’s capitalist communism……………………………………………………………… 37 Chapter 4: The economical function of the gulag and the laogai ...............………………….. 40 4.1 Fulfilling the economic goals of socialism……………………………………………... 41 4.2 -

Systematic Review of Aged Care Interventions for Older Prisoners

DOI: 10.1111/ajag.12484 Research Systematic review of aged care interventions for older prisoners Bruce A Stevens range of prisoner needs. Some examples of creative Charles Sturt University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, responses are given in the review. Australia Rhonda Shaw Key words: aged, ageing, intervention, prisoners, prisons. Charles Sturt University, Port Macquarie, New South Wales, Australia Introduction Peter Bewert and Mavis Salt The number of prisoners aged 50 years and over increased Aged Care Plus Support Services, The Salvation Army, Sydney, by 33% between 2010 and 2015 in Australia [1] and by New South Wales, Australia 23% between 2009 and 2013 in the United States [2]. Fur- ther, prisoners aged 50 years and over increased as a pro- Rebecca Alexander and Brendan Loo Gee portion of the total prison population by 101% between Charles Sturt University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2003 and 2014 in Canada [3], while prisoners aged Australia 60 years and over increased as a proportion of the total prison population by 120% between 2002 and 2013 in the Objective: The care of older prisoners is a growing United Kingdom (UK) [4]. Prisoners aged 70 years and problem. This review examined aged care interventions in over tripled between 2004 and 2014 in New Zealand [5]. prisons. Methods: A systematic review was conducted following Definitions of an ‘older prisoner’ range from 45 to 65 years preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta- and over [6,7]. There has been some agreement about classi- analyses guidelines. A total of 1186 abstracts were fying older prisoners as 50 years and over [8], because older screened for inclusion. -

The Needs and Characteristics of Older Prisoners

2014 Analytical Services exists The needs and characteristics of older to improve policy making, decision taking and practice prisoners: Results from the Surveying Prisoner by the Ministry of Justice. Crime Reduction (SPCR) survey It does this by providing Samuel Omolade robust, timely and relevant This report summarises findings from Sample 2 of Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction data and advice drawn from (SPCR), a longitudinal cohort study of 2,171 adult prisoners sentenced to between 18 research and analysis months and four years in 2006 and 2007. It focuses on the needs and characteristics of undertaken by the 115 older prisoners (aged 50 and over) on reception to custody compared to 2,056 department’s analysts and younger prisoners (18–49 years old). by the wider research community. A degree of caution should be taken in extrapolating findings due to the small numbers in the SPCR sample and that older prisoners received into prison to serve a sentence of between 18 months and four years constituted a relatively small sub-sample of all prisoners aged over 50 at the time of the survey (15% of prison receptions between June 2006 and July 2007).1 However, this study is still useful in suggesting that older prisoners may have some unique needs which should be considered in targeting © Crown copyright 2014 resources. You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit Key findings http://www.nationalarchives. Older prisoners may have greater health needs than younger prisoners.