The Illinois Task Force on Crime and Corrections Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2015 Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1490 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2625217 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1156-1239 (2015) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod EVIEW R ABSTRACT This Article introduces to legal scholarship the first sustained discussion of prison LA LAW LA LAW C abolition and what I will call a “prison abolitionist ethic.” Prisons and punitive policing U produce tremendous brutality, violence, racial stratification, ideological rigidity, despair, and waste. Meanwhile, incarceration and prison-backed policing neither redress nor repair the very sorts of harms they are supposed to address—interpersonal violence, addiction, mental illness, and sexual abuse, among others. Yet despite persistent and increasing recognition of the deep problems that attend U.S. incarceration and prison- backed policing, criminal law scholarship has largely failed to consider how the goals of criminal law—principally deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retributive justice—might be pursued by means entirely apart from criminal law enforcement. Abandoning prison-backed punishment and punitive policing remains generally unfathomable. This Article argues that the general reluctance to engage seriously an abolitionist framework represents a failure of moral, legal, and political imagination. -

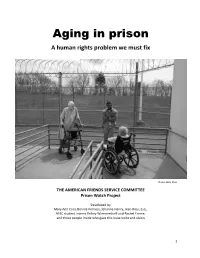

Aging in Prison a Human Rights Problem We Must Fix

Aging in prison A human rights problem we must fix Photo: Nikki Khan THE AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Prison Watch Project Developed by Mary Ann Cool, Bonnie Kerness, Jehanne Henry, Jean Ross, Esq., AFSC student interns Kelsey Wimmershoff and Rachel Frome, and those people inside who gave this issue voice and vision 1 Table of contents 1. Overview 3 2. Testimonials 6 3. Preliminary recommendations for New Jersey 11 4. Acknowledgements 13 2 Overview The population of elderly prisoners is on the rise The number and percentage of elderly prisoners in the United States has grown dramatically in past decades. In the year 2000, prisoners age 55 and older accounted for 3 percent of the prison population. Today, they are about 16 percent of that population. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of prisoners age 65 and older increased by an alarming 63 percent, compared to a 0.7 percent increase of the overall prison population. At this rate, prisoners 55 and older will approach one-third of the total prison population by the year 2030.1 What accounts for this rise in the number of elderly prisoners? The rise in the number of older people in prisons does not reflect an increased crime rate among this population. Rather, the driving force for this phenomenon has been the “tough on crime” policies adopted throughout the prison system, from sentencing through parole. In recent decades, state and federal legislators have increased the lengths of sentences through mandatory minimums and three- strikes laws, increased the number of crimes punished with life and life-without-parole and made some crimes ineligible for parole. -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

Aging of the State Prison Population, 1993–2013 E

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics MAY 2016 Special Report NCJ 248766 Aging of the State Prison Population, 1993–2013 E. Ann Carson, Ph.D., BJS Statistician, and William J. Sabol, Ph.D., former BJS Director he number of prisoners sentenced to more than FIGURE 1 1 year under the jurisdiction of state correctional Sentenced state prisoners, by age, December 31, 1993, 2003, authorities increased 55% over the past two decades, and 2013 Tfrom 857,700 in 1993 to 1,325,300 in 2013. During the same period, the number of state prisoners age 55 or older Sentenced state prisoners increased 400%, from 3% of the total state prison population 1,000,000 in 1993 to 10% in 2013 (figure 1). Between 1993 and 2003, 800,000 the majority of the growth occurred among prisoners 39 or younger ages 40 to 54, while the number of those age 55 or older 600,000 increased faster from 2003 to 2013. In 1993, the median age 40–54 of prisoners was 30; by 2013, the median age was 36. The 400,000 changing age structure in the U.S. state prison population 200,000 has implications for the future management and care 55 or older of inmates. 0 1993 2003 2013 Two factors contributed to the aging of state prisoners Year between 1993 and 2013: (1) a greater proportion of Note: Based on prisoners sentenced to more than 1 year under the jurisdiction prisoners were sentenced to, and serving longer periods of state correctional authorities. -

Older Men in Prison : Emotional, Social, and Physical Health Characteristics

OLDER MEN IN PRISON: EMOTIONAL, SOCIALl AND PHYSICAL HEALTH CHARACTERISTICS Elaine Marie Gallagher B.Sc.N., University of Windsor, 196' M.Sc., Duke University, 1976 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Special Arrangements @~laine Marie Gallagher SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY March, 1988 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Elaine Marie Gallagher Degree: .?h. D. Interdisciplinary Studies Title of thesis: Emotional, Social and Physical Health Needs of Older Men in Prison. Examining Committee: Chairman: Dr. Bruce Clayman Dean of Graduate Studies Senior Supervisor: Dr. Gloria Gutman , -,,r LC.- Director Gerontology Center and Program Dr. Ellen Gee . ., Assistant Professor, Sociology Dr. Margaret Jackson I - Assistant Professor, Criminology External Examiners Dr. Real Prefontaine _- J Director, Treatment Services and Regional Health Care, Correctional Services of Canada Dr. Cathleen Burnett - - P.ssistant Professor, Sociology - P.dministration of Justice Program, University of Missouri-Kansas City PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser Unlverslty the right to lend my thesis, proJect or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or In response to a request from the I ibrary of any other university, or other educatlonal institution, on its own behalf or for one of Its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

Restorative Justice in Prisons: Methods, Approaches and Effectiveness

Strasbourg, 29 September 2014 PC-CP (2014) 17 rev PC-CP\docs 2014\PC-CP(2014)17e rev EUROPEAN COMMITTEE ON CRIME PROBLEMS (CDPC) Council for Penological Co-operation (PC-CP) Restorative Justice in Prisons: Methods, Approaches and Effectiveness Document prepared by Gerry JOHNSTONE Professor of Law, Law School, University of Hull, United Kingdom Introduction Imprisonment of offenders is a central and seemingly indispensable part of the raft of methods used to respond to crime in contemporary societies. Whereas in dealing with other problems, such as mental disorder, modern societies have pursued policies of decarceration – relying less upon control in institutions, more upon care and control in the community – in responding to crime these societies are making increasing use of imprisonment. Walmsley (2013) estimates that, throughout the world, 10.2 million people are held in penal institutions and that prison populations are growing in all five continents at a faster rate than the general population. For the public at large, this raises little concern; indeed, there is much public support for high custody rates and for lengthy prison sentences for those who commit violent and sexual offences (Roberts, 2008). But for penal reformers and most criminologists this is a regressive trend: society is increasing its use of an outdated penal method which is ineffective (in either deterring crime or preparing offenders for life in the community upon release), inhumane, and very expensive.i Critics of imprisonment argue both for a significant reduction in its use and for the reform of prison conditions to render the practice more constructive and civilised. -

When Prison Gets Old: Examining New Challenges Facing Elderly Prisoners in America

When Prison Gets Old: Examining New Challenges Facing Elderly Prisoners In America by Benjamin Pomerance ―The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” -- Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky John H. Bunz will celebrate his ninety-second birthday in November.1 Described by observers as ―feeble-looking‖ after the death of his wife in 2010, he requires a walker to take even a couple of steps, and needs a wheelchair to travel any distance of significant length.2 Yet he still is in better health than George Sanges, age 73, who suffers from cerebral palsy, has sagging skin that is listed as ―sallow,‖ takes multiple medications twice a day, and has recently been rushed to the emergency room for heart problems.3 And both of them are far more alert than Leon Baham, a 71-year-old man who has dementia and goes into delusional bouts of yearning for the company of his now-dead wife.4 On the surface, all of these elderly, ailing men have extremely sympathetic profiles. All three need intensive medical care.5 All three have unique physical and emotional needs that are inherent to growing older.6 All three appear to be the type of ―grandfatherly‖ figures to whom our society is historically taught to show the utmost compassion and concern. Yet all three of these individuals also have a huge component of their lives which would naturally tend to turn all thoughts of sympathy and care upside-down. They are all prisoners.7 Not low-level criminals, either, but violent felony offenders with significant sentences. -

The Socioeconomic Impact of Pretrial Detention, the Papers in the Series Look at the Intersection of Pretrial Detention and Public Health, Torture, and Corruption

THE SOCIOECONOMIC IMPACT OF PRETRIAL DETENTION September 2010 PRE-PUBLICATION DRAFT Copyright © 2010 by the Open Society Institute. All rights reserved. 2 About the Global Campaign for Pretrial Justice Excessive and arbitrary pretrial detention 1 is an overlooked form of human rights abuse that affects millions of persons each year, causing and deepening poverty, stunting economic development, spreading disease, and undermining the rule of law. Pretrial detainees may lose their jobs and homes; contract and spread disease; be asked to pay bribes to secure release or better conditions of detention; and suffer physical and psychological damage that last long after their detention ends. In view of the magnitude of this worldwide problem, the Open Society Justice Initiative, together with other partners, is in the process of launching a Global Campaign for Pretrial Justice. Its principal purpose is to reduce unnecessary pretrial detention and demonstrate how this can be accomplished effectively at little or no risk to the community. The impact of indiscriminate and excessive use of pretrial detention is felt most sharply in the countries that are the focus of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Key goals on child health, gender equality, and universal education are directly inhibited by the very significant expense and opportunity lost when someone is detained and damaged through pretrial detention. 2 Current Global Campaign activities include collecting empirical evidence to document the scale and gravity of arbitrary and unnecessary pretrial detention; building communities of practice and expertise among NGOs, practitioners, researchers and policy makers; and piloting innovative practices and methodologies aimed at finding effective, low cost solutions. -

Research Into Restorative Justice in Custodial Settings

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN CUSTODIAL SETTINGS Report for the Restorative Justice Working Group in Northern Ireland Marian Liebmann and Stephanie Braithwaite CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Full Report Introduction 1 Restorative Justice 1 Community Service 2 Victim/Offender Mediation 4 Victim Enquiry Work 8 Victim/Offender Groups 8 Relationships in Prison 13 Victim Awareness Work in Prisons 15 Restorative Justice Philosophy in Prisons 17 Issues in Custodial Settings 19 Conclusion 21 Recommendations 21 Useful Organisations 22 Organisations and People Contacted 25 References and useful Publications 27 Restorative Justice in Custodial Settings Marian Liebmann and Stephanie Braithwaite Executive Summary Introduction This lays out the scope of the task. As there is very little written material or research in this area, the authors of the report have, in addition to searching the literature in the normal way, made informal contact with a wide range of professionals and practitioners working in the field of Restorative Justice. The short timescale has meant that there is still material yet to arrive. Nevertheless a good range of information has been gathered. As part of this research, the authors undertook two surveys in April 1999, one of victim/offender mediation services’ involvement with offenders in custody, one of custodial institutions reported to be undertaking Restorative Justice initiatives. Restorative Justice We have used as a starting point a definition of restorative justice by the R.J.W.G. of Northern Ireland: “Using a Restorative Justice model within the Criminal Justice System is embarking on a process of settlement in which: victims are key participants, offenders must accept responsibility for their actions and members of the communities (victims and offenders) are involved in seeking a healing process which includes restitution and restoration." Community Service The Prison Phoenix Trust carried out two surveys of community work and projects carried out by prison establishments, in 1996 and 1998. -

Aging Behind Bars: Trends and Implications of Graying Prisoners In

Aging Behind Bars Trends and Implications of Graying Prisoners in the Federal Prison System KiDeuk Kim Bryce Peterson August 2014 Acknowledgments This report was prepared with intramural support from the Urban Institute. The authors would also like to acknowledge the insightful advice and support from Laurie Robinson of George Mason University, and Julie Samuels and Miriam Becker-Cohen of the Urban Institute. Any remaining errors are the authors’ alone. About the Authors KiDeuk Kim is a senior research associate in the Justice Police Center of the Urban Institute and a visiting fellow at the Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. His current research focuses on policy evaluation in criminal justice. Bryce Peterson is a research associate in the Justice Police Center of the Urban Institute. His current research interests include various issues related to correctional populations and their families. Copyright © August 2014. Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. Cover photograph © 2013. Yahoo News/Getty Image. The nonprofit Urban Institute is dedicated to elevating the debate on social and economic policy. For nearly five decades, Urban scholars have conducted research and offered evidence-based solutions that improve lives and strengthen communities across a rapidly urbanizing world. Their objective research helps expand opportunities for all, reduce hardship among the most vulnerable, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector. The views expressed -

It's About Time

CENTER ON SENTENCING AND CORRECTIONS Tina Chiu A and GeriatricRelease Increasing Costs, Aging Prisoners, Time About It’s PR I L 2010 istockphoto.com/mrrabbit2502 Executive Summary As harsher policies have led to longer prison sentences, often with a limited possibility of parole, correctional facilities throughout the United States are home to a growing number of elderly adults. Because this population has extensive and costly medical needs, states are con- fronting the complex, expensive repercussions of their sentencing practices. To reduce the costs of caring for aging inmates—or to avert future costs—legislators and policymakers have been increasingly will- ing to consider early release for those older prisoners who are seen as posing a relatively low risk to public safety. This report is based upon a statutory review of geriatric release provi- sions, including some medical release practices that specifically refer to elderly inmates. The review was supplemented by interviews and examination of data in publicly available documents. At the end of 2009, 15 states and the District of Columbia had provi- sions for geriatric release. However, the jurisdictions are rarely using these provisions. Four factors help explain the difference between the stated intent and the actual impact of geriatric release laws: political considerations and public opinion; narrow eligibility criteria; proce- dures that discourage inmates from applying for release; and compli- cated and lengthy referral and review processes. This report offers recommendations for responding to the disparities between geriatric release policies and practice, including the following: > States that look to geriatric release as a cost-saving measure must examine how they put policy into practice. -

The Forgotten Victims: Childhood and the Soviet Gulag, 1929–1953

Number 2203 ISSN: 2163-839X (online) Elaine MacKinnon The Forgotten Victims: Childhood and the Soviet Gulag, 1929–1953 This work is licensed under a CreaƟ ve Commons AƩ ribuƟ on-Noncommercial-No DerivaƟ ve Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of PiƩ sburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is cosponsored by the University of PiƩ sburgh Press. Elaine MacKinnon Abstract This study examines a facet of Gulag history that only in recent years has become a topic for scholarly examination, the experiences of children whose par- ents were arrested or who ended up themselves in the camps. It fi rst considers the situation of those who were true “children of the Gulag,” born either in prison or in the camps. Second, the paper examines the children who were left behind when their parents and relatives were arrested in the Stalinist terror of the 1930s. Those left behind without anyone willing or able to take them in ended up in orphanages, or found themselves on their own, having to grow up quickly and cope with adult situations and responsibilities. Thirdly, the study focuses on young persons who themselves ended up in the Gulag, either due to their connections with arrested family members, or due to actions in their own right which fell afoul of Stalinist “legality,” and consider the ways in which their youth shaped their experience of the Gulag and their strategies for survival. The effects of a Gulag childhood were profound both for individuals and for Soviet society as a whole.