Gulag Vs. Laogai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult

Bard College Bard Digital Commons History - Master of Arts in Teaching Master of Arts in Teaching Spring 2018 'Long Live Chairman Mao!' The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult Angelica Maldonado Bard College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/history_mat Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Secondary Education Commons Recommended Citation Maldonado, Angelica, "'Long Live Chairman Mao!' The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult" (2018). History - Master of Arts in Teaching. 1. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/history_mat/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Master of Arts in Teaching at Bard Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History - Master of Arts in Teaching by an authorized administrator of Bard Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘Long Live Chairman Mao!’ The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult By Angelica Maldonado Bard Masters of Arts in Teaching Academic Research Project January 26, 2018 Maldonado 2 Table of Contents I. Synthesis Essay…………………………………………………………..3 II. Primary documents and headnotes……………………………………….28 a. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung b. Chairman Mao badges c. Chairman Mao swims across the Yangzi d. Bombard the Headquarters e. Mao Pop Art III. Textbook critique…………………………………………………………33 IV. New textbook entry………………………………………………………37 V. Bibliography……………………………………………………………...40 Maldonado 3 "Had Mao died in 1956, his achievements would have been immortal. Had he died in 1966, he would still have been a great man. But he died in 1976. Alas, what can one say?"1 - Chen Yun Despite his celebrated status as a founding father, war hero, and poet, Mao Zedong is often placed within the pantheon of totalitarian leaders, amongst the ranks of Mussolini, Stalin, and Hitler. -

Full Case Study

National Park Service National Park Service U. S. Department of the Interior Civic Engagement www.nps.gov/civic/ Civic Engagement and the Gulag Museum at Perm-36, Russia Through communication with former prisoners and guards and an international dialogue with other "sites of conscience," The Gulag Museum at Perm-36, Russia, is building all its programs on a foundation of civic engagement. In December 1999, National Park Service (NPS) Northeast Regional Director Marie Rust became a founding member of the International Coalition of Historic Site Museums of Conscience. At the Coalition’s first formal meeting, Ms. Rust met Dr. Victor Shmyrov, Director of the Gulag Museum at Perm-36 in Russia, another founding institution of the Coalition. Dr. Shmyrov’s museum preserves and interprets a gulag camp built under Joseph Stalin in 1946 near the city of Perm in the village of Kutschino, Russia. Known as Perm-36, the camp served initially as a regular timber production labor camp. Later, the camp became a particularly isolated and severe facility for high government officials. In 1972, Perm-36 became the primary facility in the country for persons charged with political crimes. Many of the Soviet Union’s most prominent dissidents, including Vladimir Bukovsky, Sergei Kovalev and Anatoly Marchenko, served their sentences there. It was only during the Soviet government’s period of “openness” of Glasnost, under President Mikael Gorbachev, that the camp was finally closed in 1987. Although there were over 12,000 forced labor camps in the former Soviet Union, Perm-36 is the last surviving example from the system. -

The Struggle for Human Rights

Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal Volume 17 | Issue 2 Article 14 2000 The trS uggle For Human Rights Harry Wu Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wu, Harry (2000) "The trS uggle For Human Rights," Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal: Vol. 17: Iss. 2, Article 14. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj/vol17/iss2/14 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wu: The Struggle For Human Rights ESSAY THE STRUGGLE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Harry Wu* This past April of 1999, while China's Prime Minister Zhu Ronji was being hosted in Washington, D.C., it was my honor to receive the Samuel M. Kaynard Award for Excellence in the Field of Labor Law at Hofstra University School of Law-the award named after the well- respected, late Professor Samuel M. Kaynard. The warm welcome of Professor Kaynard's family members, faculty and students of Hofstra, and one of the most moving introductions I have thus far received, given by Hofstra graduate David Feldman, made the entire event one that I shall cherish forever. I am painfully reminded that as a college student in the late 1950s in China, I was encouraged to speak my mind in class when we dis- cussed the former Soviet Union's invasion of Hungary. -

The Historical Experience of Labor: Archaeological Contributions To

4 Barbara L. Voss (芭芭拉‧沃斯) Pacific Railroad, complained about the scarcity of white labor in California. Crocker proposed that Chinese laborers would be hardworking The Historical Experience and reliable; both he and Stanford had ample of Labor: Archaeological prior experience hiring Chinese immigrants to work in their homes and on previous business Contributions to Interdisciplinary ventures (Howard 1962:227; Williams 1988:96). Research on Chinese Railroad construction superintendent J. H. Stro- Railroad Workers bridge balked but relented when faced with rumors of labor organizing among Irish immi- 劳工的历史经验:考古学对于中 grants. As Crocker’s testimony to the Pacific 国铁路工人之跨学科研究的贡献 Railway Commission later recounted: “Finally he [Strobridge] took in fifty Chinamen, and a ABSTRACT while after that he took in fifty more. Then, they did so well that he took fifty more, and he Since the 1960s, archaeologists have studied the work camps got more and more until we finally got all we of Chinese immigrant and Chinese American laborers who could use, until at one time I think we had ten built the railroads of the American West. The artifacts, sites, or twelve thousand” (Clark 1931:214; Griswold and landscapes provide a rich source of empirical informa- 1962:109−111; Howard 1962:227−228; Chiu tion about the historical experiences of Chinese railroad 1967:46; Kraus 1969a:43; Saxton 1971:60−66; workers. Especially in light of the rarity of documents Mayer and Vose 1975:28; Tsai 1986; Williams authored by the workers themselves, archaeology can provide 1988:96−97; Ambrose 2000:149−152; I. Chang direct evidence of habitation, culinary practices, health care, social relations, and economic networks. -

Announcement the International Historical, Educational, Charitable and Human Rights Society Memorial, Based in Moscow, Asks

Network of Concerned Historians NCH Campaigns Year Year Circular Country Name original follow- up 2017 88 Russia Yuri Dmitriev 2020 Announcement The international historical, educational, charitable and human rights society Memorial, based in Moscow, asks you to sign a petition in support of imprisoned historian and Gulag researcher Yuri Dmitriev in Karelia. The petition calls for Yuri Dmitriev to be placed under house arrest for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until his court case is over. The petition can be signed in Russian, English, French, Italian, German, Hebrew, Polish, Czech, and Finnish. It can be found here and here. This is the second petition for Yuri Dmitriev. The first, from 2017, can be found here. Please find below: (1) a NCH case summary (2) the petition text in English. P.S. Another historian, Sergei Koltyrin – who had defended Yuri Dmitriev and was subsequently imprisoned under charges similar to his – died in a prison hospital in Medvezhegorsk, Karelia, on 2 April 2020. Please sign the petition immediately. ========== NCH CASE SUMMARY On 13 December 2016, the Federal Security Service (FSB) arrested Karelian historian Yuri Dmitriev (1956–) and held him in remand prison on charges of “preparing and circulating child pornography” and “depravity involving a minor [his foster child, eleven or twelve years old in 2017].” The arrest came after an anonymous tip: the individual and his motives, as well as how he got the private information, remain unknown. Dmitriev said the “pornographic” photos of his foster child were taken because medical workers had asked him to monitor the health and development of the girl, who was malnourished and unhealthy when he and his wife took her in at age three with the intention of adopting her. -

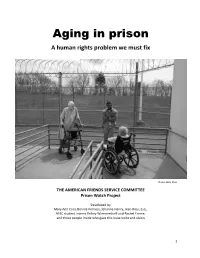

Aging in Prison a Human Rights Problem We Must Fix

Aging in prison A human rights problem we must fix Photo: Nikki Khan THE AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Prison Watch Project Developed by Mary Ann Cool, Bonnie Kerness, Jehanne Henry, Jean Ross, Esq., AFSC student interns Kelsey Wimmershoff and Rachel Frome, and those people inside who gave this issue voice and vision 1 Table of contents 1. Overview 3 2. Testimonials 6 3. Preliminary recommendations for New Jersey 11 4. Acknowledgements 13 2 Overview The population of elderly prisoners is on the rise The number and percentage of elderly prisoners in the United States has grown dramatically in past decades. In the year 2000, prisoners age 55 and older accounted for 3 percent of the prison population. Today, they are about 16 percent of that population. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of prisoners age 65 and older increased by an alarming 63 percent, compared to a 0.7 percent increase of the overall prison population. At this rate, prisoners 55 and older will approach one-third of the total prison population by the year 2030.1 What accounts for this rise in the number of elderly prisoners? The rise in the number of older people in prisons does not reflect an increased crime rate among this population. Rather, the driving force for this phenomenon has been the “tough on crime” policies adopted throughout the prison system, from sentencing through parole. In recent decades, state and federal legislators have increased the lengths of sentences through mandatory minimums and three- strikes laws, increased the number of crimes punished with life and life-without-parole and made some crimes ineligible for parole. -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

The Suppression of Communism Act

The Suppression of Communism Act http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1972_07 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Suppression of Communism Act Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 7/72 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Yengwa, Massabalala B. Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1972-03-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1972 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. Criticism of Bill in Parliament and by the Bar. The real purpose of the Act. -

Hu Jia on Behalf of the Silenced Voices of China and Tibet

Sakharov Prize 2008 Year for China Hu Jia On behalf of the silenced voices of China and Tibet Hu Jia and his wife, Zeng Jinyan, were nominated for last year's Sakharov Prize and were among the final three short-listed candidates. Hu Jia was consequently imprisoned and remains in prison to this day. Hu Jia is a prominent human rights activist who works on various issues including civil rights, environmental protection and AIDS advocacy. He was arrested shortly after his testimony on 26 November 2007 via conference call before the European Parliament's sub-committee on Human Rights. In his statement, he expressed his desire that 2008 be the “year of human rights in China”. He also pointed out that the Chinese national security department was creating a human rights disaster with one million people persecuted for fighting for human rights and many of them detained in prison, in camps or mental hospitals. He also said: "The irony is that one of the people in charge of organising the Olympics is the head of the Public Security Bureau in Beijing who is responsible for so many human rights violations. The promises of China are not being kept before the games." As a direct result of his address to members of the European Parliament, Hu Jia was arrested, charged with "inciting subversion of state power", and sentenced on 3 April 2008 to three-and-a-half years' in jail with one year denial of political rights. He was found guilty of writing articles about the human rights situation in the run-up to the Olympic Games. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

From Slavery to Mass Incarceration

loïc wacquant FROM SLAVERY TO MASS INCARCERATION Rethinking the ‘race question’ in the US ot one but several ‘peculiar institutions’ have success- ively operated to define, confine, and control African- NAmericans in the history of the United States. The first is chattel slavery as the pivot of the plantation economy and inceptive matrix of racial division from the colonial era to the Civil War. The second is the Jim Crow system of legally enforced discrimination and segregation from cradle to grave that anchored the predominantly agrarian society of the South from the close of Reconstruction to the Civil Rights revolution which toppled it a full century after abolition. America’s third special device for containing the descendants of slaves in the Northern industrial metropolis is the ghetto, corresponding to the conjoint urbanization and proletarianization of African-Americans from the Great Migration of 1914–30 to the 1960s, when it was ren- dered partially obsolete by the concurrent transformation of economy and state and by the mounting protest of blacks against continued caste exclusion, climaxing with the explosive urban riots chronicled in the Kerner Commission Report.1 The fourth, I contend here, is the novel institutional complex formed by the remnants of the dark ghetto and the carceral apparatus with which it has become joined by a linked relationship of structural symbiosis and functional surrogacy. This suggests that slavery and mass imprisonment are genealogically linked and that one cannot understand the latter—its new left review 13 jan feb 2002 41 timing, composition, and smooth onset as well as the quiet ignorance or acceptance of its deleterious effects on those it affects—without return- ing to the former as historic starting point and functional analogue. -

State Slavery Sanctioned by the 13Th Amendment

State Slavery sanctioned by the 13th Amendment HISTORY OF PRISON LABOR IN THE UNITED STATES Prison labor has its roots in slavery. After the 1861-1865 Civil War, a system of “hiring out prisoners” was introduced in order to continue the slavery tradition. Freed slaves were charged with not carrying out their sharecropping commitments (cultivating someone else’s land in exchange for part of the harvest) or petty thievery – which were almost never proven –or vagrancy (leaving the plantation in search of better opportunities) and were then “hired out” for cotton picking, working in mines and building railroads. From 1870 until 1910 in the state of Georgia, 88% of hired-out convicts were Black. In Alabama, 93% of “hired-out” miners were Black. In Mississippi, a huge prison farm similar to the old slave plantations replaced the system of hiring out convicts. The notorious Parchman plantation existed until 1972. At least 37 states have legalized the contracting of prison labor by private corporations that mount their operations inside state prisons. The list of such companies contains the cream of U.S. corporate society: IBM, Boeing, Motorola, Microsoft, AT&T, Wireless, Texas Instrument, Dell, Compaq, Honeywell, Hewlett-Packard, Nortel, Lucent Technologies, 3Com, Intel, Northern Telecom, TWA, Nordstrom’s, Revlon, Macy’s, Pierre Cardin, Target Stores, and many more. All of these businesses are excited about the economic boom generation by prison labor. Just between 1980 and 1994, profits went up from $392 million to $1.31 billion. Inmates in state penitentiaries generally receive the minimum wage for their work, but not all; in Colorado, they get about $2 per hour, well under the minimum.