Reviews: a Power Governments Cannot Suppress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chronicle WEATHER

Volume 70 Number 112 WEATHER Tuesday, Cloudy and cold. Chance of March IB. 1975 rain tonight. Duke University The Chronicle Durham, North Carolina Cahow predicts rise in minority students By Sally Rice have applied under Ihe re loss of minority students to This year's admissions gular April notification other schools, said Cahow, process will produce an plan, and these applicants, is that there is a demand. "exceptionally good yield" added Cahow. look "con particularly in northern of minority students for siderably bettor than last schools, for minority stu next year's freshman class, year's group". dents from the South. predicts director of ad Cahow makes his predic Cahow also said that the missions Clark Cahow. tion of a higher number of Admissions Committee is He also disclosed that the minority students in next aiming for no particular overall number of under year's freshman class on the number of minority stu graduate applicants to Duke basis of the fact that last dents, but will accept as is up three per cent, year, only 84 minority stu many asare qualified. whereas at most schools dents chose to conn: to Cahow revealed that the across tbe country the Duke. total number of under number of applicants has Lured by aid graduate applicants to Duke Phillip Berrigan, seen here after his release from prison in 1972, will speak either remained the same or Cahow said that original this year is 7.394. as com at Duke tonight (UPI) dropped by as much as ten ly last year. 100 minority pared with last year's 7,189. -

Daniel Berrigan SJ and the Conception of a Radical Theatre A

Title: “This is Father Berrigan Speaking from the Underground”: Daniel Berrigan SJ and the Conception of a Radical Theatre Author Name: Benjamin Halligan Affiliation: University of Wolverhampton Postal address: Dr Benjamin Halligan Director of the Doctoral College Research Hub - MD150g, Harrison Learning Centre City Campus South, University of Wolverhampton Wulfruna Street, Wolverhampton WV1 1LY United Kingdom [email protected] 01902 322127 / 07825 871633 Abstract: The letter “Father Berrigan Speaks to the Actors from Underground” suggests the conception of a radical theatre, intended as a contribution to a cultural front against the US government during a time of the escalation of the war in Vietnam. The letter was prepared further to Berrigan’s dramatization of the trial in which he and fellow anti-war activists were arraigned for their public burning of draft cards in 1968. The play was The Trial of the Catonsville Nine and its production coincided with a period in which Berrigan, declining to submit to imprisonment, continued his ministry while a fugitive. Keywords: Daniel Berrigan, underground, Jesuit, Catonsville, anti-war, theatre, counterculture, spirituality, activism, Living Theatre. Biographical note: Dr Benjamin Halligan is Director of the Doctoral College of the University of Wolverhampton. Publications include Michael Reeves (Manchester UP, 2003), Desires for Reality: Radicalism and Revolution in Western European Film (Berghahn, 2016), and the co-edited collections Mark E. Smith and The Fall: Art, Music and Politics (Ashgate, 2010), Reverberations: The Philosophy, Aesthetics and Politics of Noise (Continuum, 2012), Resonances: Noise and Contemporary Music (Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), The Music Documentary: Acid Rock to Electropop (Routledge, 2013), and The Arena Concert: Music, Media and Mass Entertainment (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015). -

Law, Justice and Disobedience Howard Zinn

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 5 Article 2 Issue 4 Symposium on Civil Disobedience 1-1-2012 Law, Justice and Disobedience Howard Zinn Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Howard Zinn, Law, Justice and Disobedience, 5 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 899 (1991). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol5/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES LAW, JUSTICE AND DISOBEDIENCE HOWARD ZINN* In the year 1978, I was teaching a class called "Law and Justice in America," and on the first day of class I handed out the course outlines. At the end of the hour one of the students came up to the desk. He was a little older than the others. He said: "I notice in your course outline you will be discussing the case of U.S. vs. O'Brien. When we come to that I would like to say something about it." I was a bit surprised, but glad that a student would take such initiative. I said, "Sure. What's your name?" He said: "O'Brien. David O'Brien." It was, indeed, his case. It began the morning of March 31, 1966. American troops were pouring into Vietnam, and U.S. -

D^J£$~/Ù /H^Nerru^ &JL.C.9U^

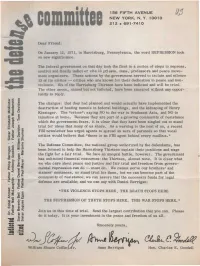

156 FIFTH AVENUE 11$ NEW YORK, N. Y. 10010 t$ committee 212 • 691-7410 Dear Friend: On January 12, 1971, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the word REPRESSION took on new significance. The federal government on that day took the first in a series of steps to repress, control and finally indict or cite 13 priests, nuns, professors and peace move ment organizers. These actions by the government served to isolate and silence 13 of its critics — critics who are known for their dedication to peace and non violence. Six of the Harrisburg Thirteen have been indicted and will be tried. The other seven, named but not indicted, have been smeared without any oppor tunity to reply. >- .C c » •-> o »2 5 The charges: that they had planned and would actually have implemented the — CD • — < T: > destruction of heating tunnels in federal buildings, and the kidnaping of Henry 2 • Q Kissinger. The "crime": saying NO to the war in Southeast Asia, and NO to 5 £ o injustice at home. Because they are part of a growing community of resistance •g « . which the government fears, it is clear that they have been singled out to stand ••= ^ § trial for ideas that many of us share. As a warning to the rest of us, a recent i_ » •; <2 FBI newsletter has urged agents to spread an aura of paranoia so that vocal m •£ Q 3 critics would believe that "there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox. " cö "• E" .* = c The Defense Committee, the national group authorized by the defendants, has S5 ? Î5 been formed to help the Harrisburg Thirteen explain their positions and wage t° c 2 the fight for a fair trial. -

Philip Berrigan Praised As 'Prophet of Peace' at Baltimore Funeral Mass

Philip Berrigan praised as ‘prophet of peace’ at Baltimore funeral Mass Hundreds of people marched through the troubled, poverty-stricken streets of West Baltimore Dec. 9 to celebrate the life of controversial Catholic peace activist Philip Francis Berrigan. Led by a cross bearer and a bagpiper playing “Amazing Grace,” they paid tribute to a man who put his Christian conscience on the line time after time, serving years in prison for his anti-war protests. The former Josephite priest, best known for burning draft files in Catonsville in the late 1960s, died of liver and kidney cancer Dec. 6 at Jonah House in Baltimore. He was 79. Clutching red and yellow roses, with some carrying peace signs and large dove figures, the mourners wound their way through the same St. Peter Claver neighborhood which Berrigan had once served as a priest. Passing boarded-up, graffiti-scrawled row houses, friends, family and admirers followed a pickup truck carrying a simple, unfinished wooden coffin with Berrigan’s remains. Painted red flowers, a cross and the words “blessed are the peacemakers” adorned the makeshift coffin, which was also accompanied by chanting, drum- beating Buddhist monks. Inside St. Peter Claver, mourners filled every pew – spilling over into the aisles and choir loft for a funeral liturgy marked by calls for social justice and an end to war plans in Iraq. Berrigan was the leader of the Catonsville Nine, a group of peace activists who burned 500 draft files using homemade napalm at a Selective Service office in Catonsville in 1968. A year earlier he poured blood on draft files in Baltimore with three others. -

Review of at Play in the Lions' Den, a Biography and Memoir of Daniel

The Journal of Social Encounters Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 9 2018 Review of At Play in the Lions’ Den, A Biography and Memoir of Daniel Berrigan by Jim Forest William L. Portier University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Portier, William L. (2018) "Review of At Play in the Lions’ Den, A Biography and Memoir of Daniel Berrigan by Jim Forest," The Journal of Social Encounters: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, 96-101. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters/vol2/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Social Encounters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Journal of Social Encounters At Play in the Lions’ Den, A Biography and Memoir of Daniel Berrigan by Jim Forest. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2017. Xiv + 336 pp. $28 US. In 1957 Daniel Berrigan (1921-2016), a thirty-six-year-old Jesuit priest, about to begin teaching New Testament at Lemoyne College in his hometown of Syracuse, New York, published his first book. A book of poetry entitled Time Without Number, it won the Lamont Poetry Award and was also nominated for a National Book Award. At the time, he realized that, “Publishers would now take almost anything I chose to compile; the question of quality was largely in my own hands and my own sense of things” (47). -

The Berrigans: Conspiracy and Conscience

":!•,%‘^'. The Berrigans: Conspiracy and Conscience But how shall we educate men to to it," Buck reported. "Phil, who is violence—have now turned to violent goodness, to a sense of one another, to given to putting things in a more earthy and bizarre methods? Or is it possible a love of the truth? And more ur- way, said it was all bullshit." that the Government has drawn mon- gently, how shall we do this in a bad Though one largely Catholic antiwar strous conclusions from flimsy evidence, time? group readily admitted to being the perhaps taking protesters' idle specu- —Daniel Berrigan, East Coast Conspiracy, Anderson de- lations with total solemnity? The first nounced Hoover for attacking the Ber- could help rekindle the fires of protest HE scenario read like an Ian Flan- rigans. If the Justice Department had that have seemed dimmer lately and Ting doodle, a picaresque fantasy. The evidence against them, he said, it should also revive lingering fear and hate of rad- cast: a ragtag band of radical pacifists, be put before a grand jury. Hoover icals. The second could again put in many of them Roman Catholics. some made no reply, but Attorney General question the Government's responsibility priests and nuns, a physics professor Mitchell needed no advice from An- and fairness in dealing with dissent and and a Moslem from Pakistan. The lead- derson. The case was already on its stir new talk of "repression." ing actors: two hotly controversial priests way to court. Last week a federal grand The indictment gave only the bare —Philip Berrigan, 47, a Josephite. -

Resist Newsletter, Sept. 1968

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 9-23-1968 Resist Newsletter, Sept. 1968 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, Sept. 1968" (1968). Resist Newsletters. 128. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/128 a call to resist ....... illegitimate authority 23 Septe~•er 1968 - 763 M~ssachusetts Avenue, i/4, Camerid~e, Mass., .Newsletter i/16 THE TRIAL OF THE CATONSVILLE NINE A REP.ORT . .ON. .THE. PARIS TALKS The trial of the Catonsville Nine (Cornell Professor Douglas Dowd, for burning draft board records will member of the Mobilization Steering begin in Baltimore on October 7. We Committee, was one of five American want to share with you some information scholars who recently spent 13 hours about and perspective on the trial, and over two days in discussions in Paris to urge you to join us in activities with North Vietnam's top negotiators. related to the event and to the more The views are his, and the statistics general needs of the anti-war movement. are those given to him and his col leagues by the North Vietnamese. The Baltimore trial will be short These figures also were checked with and highly political, both inside and U.S. records. His account of the outside the courtroom. The group has Paris meeting is here printed com decided upon a "collective defense"; plete, and it is used by permission. the team of lawyers is led by William From The Ithaca Journal, 13 September, Kunstler. They will not ask for a 1968.) jury (partly because choosing a jury is usually time-wasting and undramatic, By DOUGLAS F. -

+ Christmas 2002, Vol

JOURNAL OF THE CATHOLIC PEACE FELLOWSHIP THE HOPES AND FEARS OF ALL THE YEARS . OUT OF THE LITTLE TOWN OF BETHLEHEM, which to this day wears the wounds of war, has come the Prince of Peace. The little town is not forgotten this Christmas: manger scenes cover the landscape, from living rooms to lawns to even city halls. The images of Mary and Joseph, the magi and the shepherds, the star and the angels, and at the center, the Source—the infant Jesus—kindle hopes of love and peace and joy. As well they should. In this time of war and rumors of war, we must remember that amid our fears, Hope has sprung. And Hope will triumph. Christmas scenes—with their sym- CHRISTMAS bols and songs and stirred memories—promise us that. 2002 VOL 2. 1 Yet they teach us much more if we look closely at how Hope springs forth among us. Not a work of planning or power, the Lord’s Nativity is attended with bold and risky acts of utter obedience to God. An expectant couple is uprooted; shepherds, dumbstruck, follow the urgings of angels; kings, on blind faith, empty their treasuries and set out on a journey with an unknown end: None among our Christmas cast of pilgrims enjoys much homeland security. And soon after the holy night, family and kings are back on the move, fleeing terror. Even in Bethlehem, their apparent refuge in a dangerous world, they find no abiding home. And as pilgrim church, neither do we. Citizens of the kingdom of God, we are seeking a homeland which is the city with foundations, whose architect and maker is God. -

The Chronicle = WEATHER

Volume 70 Number 113 WEATHER Wednesday, CWtr a>) ooU. "Win < March 19. 1975 Duke University The Chronicle Durham=, Nort h Carolina Glaser appoints budget group, vows openness By Dan Caldwell In his inaaugural address to the ASDU legislature, newly-elected president Rick Glaser renewed his cam paign pledge to have ASDU be "more communicative" with students. Saying that "We must be open with ourselves," Glaser reiterated his proposals which he believes will increase ' interest in ASDU affairs. These include bi-weekly col umns in the Chronicle and monthly press conferences Rick Glaser in his inaugural address to the ASDU legislature. (Photo by Jim Conner) where Glaser will be available for questions. In addition to improved communications, Glaser also Kontum. Pieiku captured reiterated his plans to lake legislation to various campus "interest groups", with the goal once again being in creased input into student government. Conluding his remarks. Glaser promised that commit Highland defeats spark exodus tees will be more closely supervised under the Committee Review Board. Should the performance of some students persons—farmers, businessmen, Montagnard By Malcolm W. Browne on committees be regarded as unsatisfacotry. Glaser said. IC| 1975 NYT News Sanies tribesmen and soldiers—were strung out for 140 "Some people could be removed from committees if they SAIGON—The greatest exodus of refugees from miles along the sole remaining open road to the are found not doing their jobs." South Vietnam's Central Highlands in modern his safety of the seacoast. Aside from Glaser's speech, the only other business of tory was under way Tuesday, as rear-guard troops Behind them, Communist forces were poised to the meeting was an allocation of $400 for the upcoming blew up military installations they were abandon occupy a vast, economically important area they Folk Life Festival and creation of an ad hoc budget com ing and civilian stragglers burned down their had never before entirely conquered, even during mittee. -

Deacon Derek Scalia '05 Builds Communities for Peace and Justice

THE MAGAZINE OF RAVEN NATION SPRING 2020 PierceDeacon Derek Scalia ’05 builds communities for peace and justice. In spite of snowy conditions, about 500 people came to Franklin Pierce’s Rindge campus on Monday, February 10, to attend a Bernie Sanders town hall. This event took place the day before New Hampshire’s fi rst-in-the-nation primary. Here, members of the press set up behind the audience to fi lm Sanders’s speech. ANDREW CUNNINGHAM SpringVOL. 38, NO. 1 20 Features 32 22 | Front Row Seat 32 | “As we say in the village” From New Hampshire to Iowa (and back), Gabe Norwood ’18 preserves 17th-century students involved in the Marlin Fitzwater history as a first-person educator at Center gain valuable experience as political Plimoth Plantation. journalists. BY JANA F. BROWN BY JANA F. BROWN 28 | Brave and Consistent Work Derek Scalia ’05 builds communities for peace and justice. BY JULIE RIZZO On the Cover Derek Scalia ’05 PHOTOGRAPHER: ANDREW CUNNINGHAM How are we doing? What do you like? What stories do we need to know about? Let us hear from you: [email protected] 2 PIERCE SPRING 2020 Departments 5 President’s Message Preparing to thrive 6 Ravenings Archives go digital, cutting the ribbon at the 20 38 College of Business, highlighting the Jessica Marulli Scholarship winner, Clothing Closet comes to life, student journalists capture Radically Rural highlights, Hannings documentary in progress, Doria Brown ’16 leads sustainability efforts in N.H., University announces formation of the Institute for Climate Action, catching up with Trustees Frederick 22 Pierce and Jonathan Slavin ’92, Lori Shibinette M.B.A. -

John of the Cross

John of the Cross This article is about the Spanish saint. For the national personification of the Philippines, see Juan dela Cruz. Saint John of the Cross, O.C.D. (Spanish: San Juan de la Cruz; 1542[1] – 14 December 1591), was a major figure of the Counter-Reformation, a Spanish mystic, a Roman Catholic saint, a Carmelite friar and a priest who was born at Fontiveros, Old Castile. John of the Cross was a reformer of the Carmelite Order and is considered, along with Saint Teresa of Ávila, as a founder of the Discalced Carmelites. He is also known for his writings. Both his poetry and his studies on the growth of the soul are considered the summit of mystical Spanish literature and one of the peaks of all Spanish lit- erature. He was canonized as a saint in 1726 by Pope Benedict XIII. He is one of the thirty-five Doctors of the Church. 1 Life 1.1 Early life and education Statues in Fontiveros of John of the Cross, erected in 1928 by He was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez[3] into a converso popular subscription by the townspeople. family (descendents of Muslim or Jewish converts to Christianity) in Fontiveros, near Ávila, a town of around 2,000 people.[4][5] His father, Gonzalo, was an accoun- Spaniard St. Ignatius of Loyola. In 1563[11] he en- tant to richer relatives who were silk merchants. How- tered the Carmelite Order, adopting the name John of ever, when in 1529 he married John’s mother, Catalina, St.