Law, Justice and Disobedience Howard Zinn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanities 1

Humanities 1 Humanities HUM 1100. Philosophy: Good Questions for Life. 2 Units. HUM 1100A. Studies in Humanities: The Classical Word. 2-3 Unit. HUM 1110. Literature: Reading Cultures. 2 Units. HUM 1110A. Studies in the Humanities: Renaissance To Enlightenment. 2-3 Unit. HUM 1120. Art History: Visual Literacy. 2 Units. HUM 1120A. Studies in the Humanities: Contemporary Voices. 2-3 Unit. HUM 1510. Independent Study: Humanities. 1-5 Unit. HUM 2500. Prior Learning: Humanities. 1-5 Unit. HUM 3030. Twenty-First Century Latin American Social Movements. 3-4 Unit. HUM 3040. Birds in the Field & Human Imagination. 3-4 Unit. The purpose of this course is to engage a tradition that spans millennia and every culture: a human fascination with birds. Taking a multidisciplinary approach, we will explore birds through many lens and avenues. As naturalists, we will seek out birds in the wild, experimenting with different approaches to observation. We will consider common themes in the life circumstances of birds, as well as explore the impact of human civilization on the ecology of natural habitats. Further, we will explore birds as symbols of the human imagination as expressed. HUM 3070. Borderlands: Exploring Identities & Borders. 3-4 Unit. HUM 3090. Queer Perspectives: Applications in Contemporary Soc. 3-4 Unit. This course critically addresses the term ?queer,? its changing definition, and the particular ways in which it has described, marginalized and excluded people, communities and modes of thought. Using both academic and empirical examples, students will explore and uncover how queer thought has influenced such diverse human endeavors as civil rights, athletics, literature, pop culture, and science. -

Reviews: a Power Governments Cannot Suppress

Reviews: A Power Governments Cannot Suppress Spring 2007 Rethinking Schools Books Bringing History Alive A new compilation of essays by Howard Zinn A Power Governments Cannot Suppress By Howard Zinn (City Lights, 2006) 308 pp. $16.95 By Erik Gleibermann In a new compilation of essays, activist historian Howard Zinn tells the story of Sergeant Jeremy Feldbusch who wakes up blind five weeks after a shell explosion in the Iraq War puts him in a coma. Jeremy's father sits beside him in the army hospital and wonders "if God thought you had seen enough killing." Zinn, our elder statesman of progressive American history, begins his opening essay with this story to reflect back on a long, painful pattern of young people enticed to enlist in seemingly just military causes whose devastated lives become forgotten statistics. This flashback narrative approach is Zinn's compelling trademark, bringing history alive by casting current political controversies in a stark historical light that reveals how today's injustices echo through American history. As in A People's History of the United States, which many conscientious high school teachers use to counterbalance the ideological slant of standard history texts, A Power Governments Cannot Suppress will help students harness history as a critical tool. Zinn details the ugly underside of oppression in U.S. history, while celebrating longignored examples of courageous resistance that can inspire the activist looking for models. In one essay he describes how a speech he gave to memorialize the Boston Massacre at the city's landmark Faneuil Hall became an occasion to reflect on massacres American forces have perpetrated since Puritan settlers slaughtered over 600 Pequot Indians in 1636. -

The Counterculture of the 1960S in the United States: an ”Alternative Consciousness”? Mélisa Kidari

The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An ”Alternative Consciousness”? Mélisa Kidari To cite this version: Mélisa Kidari. The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An ”Alternative Conscious- ness”?. Literature. 2012. dumas-00930240 HAL Id: dumas-00930240 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00930240 Submitted on 14 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An "Alternative Consciousness"? Nom : KIDARI Prénom : Mélisa UFR ETUDES ANGLOPHONES Mémoire de master 1 professionnel - 12 crédits Spécialité ou Parcours : parcours PLC Sous la direction de Andrew CORNELL Année universitaire 2011-2012 The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An "Alternative Consciousness"? Nom : KIDARI Prénom : Mélisa UFR ETUDES ANGLOPHONES Mémoire de master 1 professionnel - 12 crédits Spécialité ou Parcours : parcours PLC Sous la direction de Andrew CORNELL Année universitaire 2011-2012 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Mr. Andrew Cornell for his precious advice and his -

For All the People

Praise for For All the People John Curl has been around the block when it comes to knowing work- ers’ cooperatives. He has been a worker owner. He has argued theory and practice, inside the firms where his labor counts for something more than token control and within the determined, but still small uni- verse where labor rents capital, using it as it sees fit and profitable. So his book, For All the People: The Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, reached expectant hands, and an open mind when it arrived in Asheville, NC. Am I disappointed? No, not in the least. Curl blends the three strands of his historical narrative with aplomb, he has, after all, been researching, writing, revising, and editing the text for a spell. Further, I am certain he has been responding to editors and publishers asking this or that. He may have tired, but he did not give up, much inspired, I am certain, by the determination of the women and men he brings to life. Each of his subtitles could have been a book, and has been written about by authors with as many points of ideological view as their titles. Curl sticks pretty close to the narrative line written by worker own- ers, no matter if they came to work every day with a socialist, laborist, anti-Marxist grudge or not. Often in the past, as with today’s worker owners, their firm fails, a dream to manage capital kaput. Yet today, as yesterday, the democratic ideals of hundreds of worker owners support vibrantly profitable businesses. -

!["That [Zinn] Was Considered Radical Says Way More About This Society Than It Does About Him." (Herbert 2010)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7420/that-zinn-was-considered-radical-says-way-more-about-this-society-than-it-does-about-him-herbert-2010-987420.webp)

"That [Zinn] Was Considered Radical Says Way More About This Society Than It Does About Him." (Herbert 2010)

-~(~~- REMEMBERING ZINN: CONFESSIONS OF A RADICAL HISTORIAN MICHAEL SNODGRASS "That [Zinn] was considered radical says way more about this society than it does about him." (Herbert 2010) In the mid-1990s, at the University of Texas, I and my fellow traveling graduate students organized a Radical History Reading Group. As scholarship, "radical history" implied two things for us: a critical rendering of the past from a leftist perspective, and a scholarship that examines history "from the roots," not only recovering the silenced perspectives of ordinary people but also foregrounding their grassroots and progressive movements that challenged entrenched systems of power and injustice. Our reading group was a modest attempt to engage with what we considered to be cutting-edge scholarship, to share and discuss our own research papers, and to then retreat to the hole-in the-wall bars along Austin's Guadalupe Street. Our own interests as radical historians ranged widely: Cuban slave rebels, the American Indian Movement, Argentine anarchists, southern abolitionists, bandits in the US-Mexican borderlands. But we all embraced the idea that the past should be analyzed and narrated from the perspective of the oppressed, and of those who struggled on behalf of the underdogs. So upon receiving funding from our history department to host our first guest speaker we instinctively invited Howard Zinn, a self-confessed radical, a historian - a Radical Historian like us. Professor Zinn accepted our offer. It was 1995. The first revised edition of A People's History of the United States was newly released. His sweeping 600-page survey of U.S. -

Howard Zinn on Dissent, Democracy, and Education

REVITALIZING POLITICS NOW AND THEN: HOWARD ZINN ON DISSENT, DEMOCRACY, AND EDUCATION Aaron Cooley This paper presents a discussion of Howard Zinn's intellectual and political ideas. Through the analysis of selections from his immense body of work, several interrelated themes emerge. Drawing more attention to these notions of dissent and democracy is crucial to revi talizing education at all levels and vital to advancing the public dis course towards progressive goals. Howard's remarkable life and work are summarized best in his own words. His primary concern, he explained, was "the countless small actions of unknown people" that lie at the roots of "those great moments" that enter the historical record-a record that will be pro foundly misleading, and seriously disempowering, if it is tom from these roots as it passes through the filters of doctrine and dogma. His life was always closely intertwined with his writings and innu merable talks and interviews. It was devoted, selflessly, to empow erment of the unknown people who brought about great moments. (Chomsky 2010,2) Introduction In life, Howard Zinn was controversial. Upon his passing in 2010, even some of his obituaries were unable to avoid controversy. The prime and sorry example was a brief story on National Public Radio that discussed his work and its context: Professor, author and political activist Howard Zinn died yesterday. Considered the people's historian, Zinn's book, A People's History of the United States, was unabashedly leftist. It celebrated the historical contribution of feminists, workers and people of color when other books did not. -

The Chronicle WEATHER

Volume 70 Number 112 WEATHER Tuesday, Cloudy and cold. Chance of March IB. 1975 rain tonight. Duke University The Chronicle Durham, North Carolina Cahow predicts rise in minority students By Sally Rice have applied under Ihe re loss of minority students to This year's admissions gular April notification other schools, said Cahow, process will produce an plan, and these applicants, is that there is a demand. "exceptionally good yield" added Cahow. look "con particularly in northern of minority students for siderably bettor than last schools, for minority stu next year's freshman class, year's group". dents from the South. predicts director of ad Cahow makes his predic Cahow also said that the missions Clark Cahow. tion of a higher number of Admissions Committee is He also disclosed that the minority students in next aiming for no particular overall number of under year's freshman class on the number of minority stu graduate applicants to Duke basis of the fact that last dents, but will accept as is up three per cent, year, only 84 minority stu many asare qualified. whereas at most schools dents chose to conn: to Cahow revealed that the across tbe country the Duke. total number of under number of applicants has Lured by aid graduate applicants to Duke Phillip Berrigan, seen here after his release from prison in 1972, will speak either remained the same or Cahow said that original this year is 7.394. as com at Duke tonight (UPI) dropped by as much as ten ly last year. 100 minority pared with last year's 7,189. -

Daniel Berrigan SJ and the Conception of a Radical Theatre A

Title: “This is Father Berrigan Speaking from the Underground”: Daniel Berrigan SJ and the Conception of a Radical Theatre Author Name: Benjamin Halligan Affiliation: University of Wolverhampton Postal address: Dr Benjamin Halligan Director of the Doctoral College Research Hub - MD150g, Harrison Learning Centre City Campus South, University of Wolverhampton Wulfruna Street, Wolverhampton WV1 1LY United Kingdom [email protected] 01902 322127 / 07825 871633 Abstract: The letter “Father Berrigan Speaks to the Actors from Underground” suggests the conception of a radical theatre, intended as a contribution to a cultural front against the US government during a time of the escalation of the war in Vietnam. The letter was prepared further to Berrigan’s dramatization of the trial in which he and fellow anti-war activists were arraigned for their public burning of draft cards in 1968. The play was The Trial of the Catonsville Nine and its production coincided with a period in which Berrigan, declining to submit to imprisonment, continued his ministry while a fugitive. Keywords: Daniel Berrigan, underground, Jesuit, Catonsville, anti-war, theatre, counterculture, spirituality, activism, Living Theatre. Biographical note: Dr Benjamin Halligan is Director of the Doctoral College of the University of Wolverhampton. Publications include Michael Reeves (Manchester UP, 2003), Desires for Reality: Radicalism and Revolution in Western European Film (Berghahn, 2016), and the co-edited collections Mark E. Smith and The Fall: Art, Music and Politics (Ashgate, 2010), Reverberations: The Philosophy, Aesthetics and Politics of Noise (Continuum, 2012), Resonances: Noise and Contemporary Music (Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), The Music Documentary: Acid Rock to Electropop (Routledge, 2013), and The Arena Concert: Music, Media and Mass Entertainment (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015). -

High School: Virginia and US History Historical Fiction: • the Jungle, Upton Sinclair -- Particularly Useful with 11Th Graders When English Teacher Assigns It

High School: Virginia and US History Historical fiction: • The Jungle, Upton Sinclair -- particularly useful with 11th graders when English teacher assigns it. Also could be useful in excerpted form in a specially edited for school use book. See particularly chapter 14. • The Killer Angels, by Michael Shaara, The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about the Battle of Gettysburg. History books: • A People’s History of the United States: 1492—Present, by Howard Zinn. Clear point of view taken here, effective to use selected chapters with students to stimulate discussion and send students into evidence to support or oppose thesis. • Putting the Movement Back Into Civil Rights Teaching: A Resource Guide for K-12 Classrooms. Book is a collection of lessons, readings, photographs, primary source documents, and interviews, to help students go beyond the “heroes approach.” Videos: • Eyes on the Prize video series: NOTE – big copyright problem recently limiting its availability. Consider The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader, a collection of original documents, speeches and firsthand of the black struggle for freedom from 1954 to 1990. • The Patriot: The debate in the S.C. statehouse sums up the SOL perfectly! I also who the battle scene that Mel and Heath Ledger see from the house. Warning- watch out for the decapitating cannon ball! • Gettysburg: Yes, a 3 hour long film, but I use the scene in the woods before Picketts Charge and the charge itself. It pretty much sums up the whole war in thirty minutes. • Far and Away: Hollywood's version of late 19th century immigration and western settlement. -

Korea and the Global Struggle for Socialism a Perspective from Anthropological Marxism

Korea and the Global Struggle for Socialism A Perspective from Anthropological Marxism Eugene E Ruyle Emeritus Professor of Anthropology and Asian Studies California State University, Long Beach Pablo Picasso, Massacre in Korea (1951) CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................. 2 What Is Socialism and Why Is It Important? .................................................. 3 U.S. Imperialism in Korea ...................................................................................18 Defects in Building Socialism in Korea ..........................................................26 1. Nuclear weapons 2. Prisons and Political Repression 3. Inequality, Poverty and Starvation 4. The Role of the Kim family. Reading “Escape from Camp 14.” A Political Review.................................37 For Further Study:.................................................................................................49 References cited.....................................................................................................50 DRAFT • DO NOT QUOTE OR CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION Introduction Even on the left, the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (DPRK) is perhaps the most misunderstood country on our Mother Earth. Cuba and Vietnam both enjoy support among wide sectors of the American left, but north Korea is the object of ridicule and scorn among otherwise intelligent people. In order to clear away some of the misunderstanding, we can do no better than quote -

D^J£$~/Ù /H^Nerru^ &JL.C.9U^

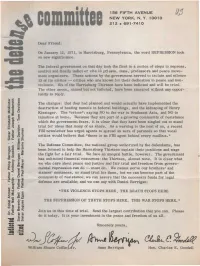

156 FIFTH AVENUE 11$ NEW YORK, N. Y. 10010 t$ committee 212 • 691-7410 Dear Friend: On January 12, 1971, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the word REPRESSION took on new significance. The federal government on that day took the first in a series of steps to repress, control and finally indict or cite 13 priests, nuns, professors and peace move ment organizers. These actions by the government served to isolate and silence 13 of its critics — critics who are known for their dedication to peace and non violence. Six of the Harrisburg Thirteen have been indicted and will be tried. The other seven, named but not indicted, have been smeared without any oppor tunity to reply. >- .C c » •-> o »2 5 The charges: that they had planned and would actually have implemented the — CD • — < T: > destruction of heating tunnels in federal buildings, and the kidnaping of Henry 2 • Q Kissinger. The "crime": saying NO to the war in Southeast Asia, and NO to 5 £ o injustice at home. Because they are part of a growing community of resistance •g « . which the government fears, it is clear that they have been singled out to stand ••= ^ § trial for ideas that many of us share. As a warning to the rest of us, a recent i_ » •; <2 FBI newsletter has urged agents to spread an aura of paranoia so that vocal m •£ Q 3 critics would believe that "there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox. " cö "• E" .* = c The Defense Committee, the national group authorized by the defendants, has S5 ? Î5 been formed to help the Harrisburg Thirteen explain their positions and wage t° c 2 the fight for a fair trial. -

Philip Berrigan Praised As 'Prophet of Peace' at Baltimore Funeral Mass

Philip Berrigan praised as ‘prophet of peace’ at Baltimore funeral Mass Hundreds of people marched through the troubled, poverty-stricken streets of West Baltimore Dec. 9 to celebrate the life of controversial Catholic peace activist Philip Francis Berrigan. Led by a cross bearer and a bagpiper playing “Amazing Grace,” they paid tribute to a man who put his Christian conscience on the line time after time, serving years in prison for his anti-war protests. The former Josephite priest, best known for burning draft files in Catonsville in the late 1960s, died of liver and kidney cancer Dec. 6 at Jonah House in Baltimore. He was 79. Clutching red and yellow roses, with some carrying peace signs and large dove figures, the mourners wound their way through the same St. Peter Claver neighborhood which Berrigan had once served as a priest. Passing boarded-up, graffiti-scrawled row houses, friends, family and admirers followed a pickup truck carrying a simple, unfinished wooden coffin with Berrigan’s remains. Painted red flowers, a cross and the words “blessed are the peacemakers” adorned the makeshift coffin, which was also accompanied by chanting, drum- beating Buddhist monks. Inside St. Peter Claver, mourners filled every pew – spilling over into the aisles and choir loft for a funeral liturgy marked by calls for social justice and an end to war plans in Iraq. Berrigan was the leader of the Catonsville Nine, a group of peace activists who burned 500 draft files using homemade napalm at a Selective Service office in Catonsville in 1968. A year earlier he poured blood on draft files in Baltimore with three others.