Interview with Harry W. Shlaudeman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface: Argentine-United States Relations As Perón Assumed the Presidency

Beneath the Surface: Argentine-United States Relations as Perón Assumed the Presidency Vivian Reed June 5, 2009 HST 600 Latin American Seminar Dr. John Rector 1 Juan Domingo Perón was elected President of Argentina on February 24, 1946,1 just as the world was beginning to recover from World War II and experiencing the first traces of the Cold War. The relationship between Argentina and the United States was both strained and uncertain at this time. The newly elected Perón and his controversial wife, Eva, represented Argentina. The United States’ presence in Argentina for the preceding year was primarily presented through Ambassador Spruille Braden.2 These men had vastly differing perspectives and visions for Argentina. The contest between them was indicative of the relationship between the two nations. Beneath the public and well-documented contest between Perón and United States under the leadership of Braden and his successors, there was another player whose presence was almost unnoticed. The impact of this player was subtlety effective in normalizing relations between Argentina and the United States. The player in question was former United States President Herbert Hoover, who paid a visit to Argentina and Perón in June of 1946. This paper will attempt to describe the nature of Argentine-United States relations in mid-1946. Hoover’s mission and insights will be examined. In addition, the impact of his visit will be assessed in light of unfolding events and the subsequent historiography. The most interesting aspect of the historiography is the marked absence of this episode in studies of Perón and Argentina3 even though it involved a former United States President and the relations with 1 Alexander, 53. -

University of Birmingham the Eisenhower Administration and U.S. Foreign and Economic Policy Towards Latin America from 1953 to 1

University of Birmingham The Eisenhower Administration and U.S. Foreign and Economic Policy towards Latin America from 1953 to 1961 By Yu-Cheng Teng A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies School of Government and Society College of Social Science University of Birmingham Edgbaston Birmingham B15 2TT September 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i ABSTRACT The thesis aims to examine Eisenhower’s foreign policy towards Latin America from 1953 to 1961. In order to win the Cold War, the leading bureaucrats were split over different approaches needed to achieve policy objectives in Latin America within the hierarchically regularized machinery- but it was not necessarily welcomed by every Latin American nation. There were three problems with Eisenhower’s staff structuring arrangement towards Latin America: (a) politicization of U.S.-Latin American relations from 1953 to 1961 by senior U.S. bureaucrats with an anti-communism agenda for Latin American development; (b) neglect of Latin American requests for public funds before 1959; (c) bureaucratic conflicts over different methods to achieve foreign policy objectives, often resulting in tensions between policy and operations. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

Cabot, Elizabeth Lewis

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Service Spouse Series ELIZABETH LEWIS CABOT Interviewed by: Jewell Fenzi Initial interview date: April 28, 1987 TABLE OF CONTENTS Mrs. abot accompanied her husband, Ambassador John Moors abot, on his Foreign Service assignments in the United States and abroad Background Born in Mexico ity, Mexico Education: Sarbonne, Paris, France: Vassar ollege Married John Moors abot in 1,3. Family background Posts of Assignment Mexico ity, Mexico 1,3. Social Secretary to wife of Ambassador lark Ambassador and Mrs. 0euben lark Marriage 0io de Janeiro, Bra1il 1,3.21,33 Environment offee US4 economies Birth of children Embassy staff Instructions from the Ambassador 6ork and recreation Portuguese language study Bra1ilian work and play schedule Sao Paulo 0evolution hange of ambassadors and routine Naval and military missions The Hague, Netherlands 1,3321,38 Birth of child Post formality 1 Marriage of Juliana Dutch language study Evacuation to Stockholm European travel Stockholm, Sweden 1,38 Housing at Peruvian embassy 4uatemala ity, 4uatemala 1,3821,41 President 4eneral Jorge Ubico astaneda 4erman submarine activity British aribbean needs 4erman colony 6ashington, D 1,4121,43 Buenos Aires, Argentina 1,4321,46 Ambassador Spruille Braden ;Peron ”si=, Braden ”no= Argentineans in Paris European immigrants Ambassador 4eorge Strausser Messersmith Belgrade, Yugoslavia 1,46 Mikhailovich Tito=s policies Bombing destruction Shortages Environment Muslim ruins and architecture Monasteries Ethnic controversies ommunism 6ashington, D 1,4621,47 National 6ar ollege Nanking/Shanghai, hina 1,4721,4, 6ithout children ommunists hina Hands Ambassador John Aeighton Stuart Mao Tse2tung Madam hiang Bai2shek Soong family 2 Aocal travel Jack Service John Paton Davies John arter Vincent New York ity 1,4,21,30 United Nations, Aake Success Mrs. -

Cheek, James R

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR JAMES RICHARD CHEEK Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: September 13, 2010 Copyright 2012 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Georgia, raised in Arkansas Racial segregation University of Arkansas; Arkansas State Teachers College (Re-named University of Central Arkansas)% American University US Army, ermany (195,-195-) .ashington, D.C.0 National 2ducation Association (12A) 1959-19-1 2ntered the Foreign Service in 19-1 3arriage Philip 4aiser State Department0 Foreign Service Institute0 Spanish 19-1-18-2 language study Santiago, Chile0 Rotation Officer 1982-1988 President 2duardo Frei 9ohn 9ova Strikes and violence 2conomy 2nvironment Political Parties Communists Alliance for Progress USAID Population Ambassador Charles Cole Allende London, 2ngland0 Consular/Political Officer 1988-19-- 3iddle 2ast, 2ast of Suez 9udy arland 1 Liaison with Foreign Office Vietnam Flags Over Vietnam Ambassador David Bruce Adlai Stevenson death Operations 9ack Vaughn Ditchley House Conference Congressional Delegations 9oan Auten Visas Charley ilbert Department of State0 Desk Officer, Newly Independent 19---19-7 British Colonies Countries covered Leeward and .indward Islands Cuba Puerto Rico British AAssociated StatesB Antigua Tracking Station US official recognition of States Barbados delegation British policy ambling casinos Puerto Rico independence USAID Labor Party Rio de 9aneiro, Brazil0 Deputy Director, Peace Corps 19-7-19-9 Circumstances of assignment Program Operations Housing overnment US Ambassadors Rio de 9aneiro0 Transportation and Communication Officer (TCO) 19-9-1971 Operations Ambassador .illiam Rountree Steven Lowe 2mbassy Brasilia Civil aviation overnment Brazilian diplomats State enterprises 2 Brazilian army 4ubitschek Human Rights Ambassador Burk 2lbrick kidnapping 4idnappings Human Rights Soviets 3anagua, Nicaragua0 Political Counselor 1971-197, Ambassador Turner and 3rs. -

G ATEMALA by Helen Simon Travis and A

THE TRUTH ABOUT G ATEMALA By Helen Simon Travis and A. B. Magil About the Authors HELEN SIMON TRAVIS visited Guatemala in 1953, where she interviewed outstanding government, trade union, peasant, and cultural leaders. Her stirring report on developments in that country is based on eye-witness observation. A. B. MAGIL visited -Guatemala in 1951 and again in 1954. He is the author 'of numerous books and pamphlets, and is widely known as a writer, lecturer, and educator. He is pres ently associate editor of Masses & Mainstream. The drawing on the cover of this pamphlet is from a poster by the distinguished Mexican artist, Alberto Beltran. The quetzal bird is the national symbol of Guatemala. Published by NEW CENTURY PUBLISHERS, 832 Broadway, New York 3, N. Y. April, 1954 PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. ~. 209 By HELEN SIMON TRAVIS and A. B. MAGIL- It was Sunday, March 29, 1953. Two hundred men donned their new uniforms, grabbed their new rilles, grenades, ma chine-guns. Swiftly they descended on the town of Salama, a provincial capital not far from Guatemala City. They seized the mayor, others, representing the democratic authority of the state. They cut telephone and telegraph lines. Then they awaited news of other successful uprisings throughout this isolated democratic Central American republic. But the ne~Ts never came. l<t had spent a quiet, sunshiny Sunday in the country. I only learned about Salama the next day, and then it was all over. The 200 held on for 12 hours, but no masses flocked to their anti-democratic banners. -

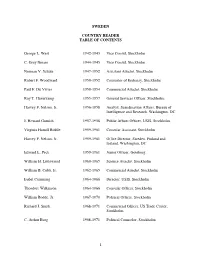

Table of Contents

SWEDEN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George L. West 1942-1943 Vice Consul, Stockholm C. Gray Bream 1944-1945 Vice Consul, Stockholm Norman V. Schute 1947-1952 Assistant Attaché, Stockholm Robert F. Woodward 1950-1952 Counselor of Embassy, Stockholm Paul F. Du Vivier 1950-1954 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Roy T. Haverkamp 1955-1957 General Services Officer, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1956-1958 Analyst, Scandinavian Affairs, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC J. Howard Garnish 1957-1958 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Virginia Hamill Biddle 1959-1961 Consular Assistant, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1959-1961 Office Director, Sweden, Finland and Iceland, Washington, DC Edward L. Peck 1959-1961 Junior Officer, Goteborg William H. Littlewood 1960-1965 Science Attaché, Stockholm William B. Cobb, Jr. 1962-1965 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Isabel Cumming 1964-1966 Director, USIS, Stockholm Theodore Wilkinson 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Stockholm William Bodde, Jr. 1967-1970 Political Officer, Stockholm Richard J. Smith 1968-1971 Commercial Officer, US Trade Center, Stockholm C. Arthur Borg 1968-1971 Political Counselor, Stockholm 1 Haven N. Webb 1969-1971 Analyst, Western Europe, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC Patrick E. Nieburg 1969-1972 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Gerald Michael Bache 1969-1973 Economic Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1969-1974 Desk Officer, Scandinavian Countries, USIA, Washington, DC William Bodde, Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC Arthur Joseph Olsen 1971-1974 Political Counselor, Stockholm John P. Owens 1972-1974 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC James O’Brien Howard 1972-1977 Agricultural Officer, US Department of Agriculture, Stockholm John P. Owens 1974-1976 Political Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1974-1977 Press Attaché, USIS, Stockholm David S. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WILLIAM P. STEDMAN, JR. In

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WILLIAM P. STEDMAN, JR. Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 23, 1989 Copyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Entry into the Foreign Service 1 47 Junior officers Latin American speciali%ation Buenos Aires, Argentina 1 47-1 50 Costa ,ica 1 50-1 52 A.D officer, /uatemala 1 5 -1 01 Political and economic pro1lems Loan program Economic officer, 2e3ico City 1 01-1 03 Alliance for Progress Am1assador Thomas C. 2ann Central Ban6 of 2e3ico Economic Policy, A,A 1 03-1 00 Lending programs Human rights Economic7A.D officer, Peru 1 00-1 08 F-5 aircraft .PC Country directory, A,A 1 08-1 71 Hic6enlooper Amendment pro1lems with Peru :.S. private financial interests in Latin America Peruvian earthqua6e :ruguay7Argentina affairs Am1assador to Bolivia 1 73-1 77 1 :.S. interests in Bolivia Bolivian dependence on :.S. Kissinger visit Narcotics pro1lem /ulf Oil Pro1lem Em1assy staffing Deputy Assistant Secretary, A,A 1 77-1 78 Human rights Career reflections INTERVIEW Q: Mr. Ambassador, could you e(plain how you became interested in foreign affairs* STED2AN: . guess this goes all the way bac6 to my youth. was born and raised in Baltimore. 2y father had been a schoolteacher, and went into the insurance business to ma6e enough money to 6eep us going. He was fascinated with foreign affairs. While in college, he had ta6en a year off and spent that time in /ermany. As a matter of fact, he 1ecame very interested himself in pursuing a career as a consul. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 1955

iJPw* lllM wm ■L \ ■pHap^ \\ \ ' / rj|(? V \ \ A \ 1 \\ VvV\-\ m\\\ \ * \ \ |mP ... may I suggest you enjoy the finest whiskey that money can buy 100 PROOF BOTTLED IN BOND Arnctm OsT uNlve«SF((f o<3 VJOUD j IKUM A .■. -V.ED IN B .n>.,v°vt 1N| *&9*. BOTTLED IN BOND KENTUCKY STRAIGHT 4/ KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY . oiniuto AND tomio IT I w HARPER DISTILLING COWART — lOUliVIUI UNIVCIt- - KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY, BOTTLED IN BOND, 100 PROOF, I. W. HARPER DISTILLING COMPANY, LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY World’s finest High Fidelity phonographs and records are RCA’s “New Orthophonic” NEW THRILLS FOR MUSIC-LOVERS! Orthophonic High Fidelity records RCA components and assemble your For the first time—in your own home that capture all the music. And New own unit, or purchase an RCA in¬ —hear music in its full sweep and Orthophonic High Fidelity phono¬ strument complete, ready to plug magnificence! RCA’s half-century graphs reproduce all the music on in and play! For the highest quality research in sound has produced New the records! You may either buy in High Fidelity it’s RCA Victor! ASSEMBLE YOUR OWN SYSTEM. Your choice of RCA READY TO PLUG IN AND PLAY. Complete RCA High intermatched tuners, amplifiers, automatic record Fidelity phonograph features three-speed changer, changers, speakers and cabinets may be easily as¬ 8-inch “Olson-design” speaker, wide-range amplifier, sembled to suit the most critical taste. Use your own separate bass and treble controls. Mahogany or limed cabinets if desired. See your RCA dealer’s catalog. oak finish. -

Guatemalan Exiles, Caribbean Basin Dictators, Operation PBFORTUNE

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Guatemalan Exiles, Caribbean Basin Dictators, Operation PBFORTUNE, and the Transnational Counter-Revolution against the Guatemalan Revolution, 1944-1952 Aaron Coy Moulton University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons, and the Latin American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Moulton, Aaron Coy, "Guatemalan Exiles, Caribbean Basin Dictators, Operation PBFORTUNE, and the Transnational Counter- Revolution against the Guatemalan Revolution, 1944-1952" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1533. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1533 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Guatemalan Exiles, Caribbean Basin Dictators, Operation PBFORTUNE, and the Transnational Counter-Revolution against the Guatemalan Revolution, 1944-1952 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Aaron Moulton University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in Latin American Studies, Spanish, and Mathematics, 2007 University of Kansas Master of Arts in Latin American Studies, 2009 May 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. __________________________________ -

The Foreign Service Journal, May 1957

Jcticnl Q.KC MPO RTED) O.F.C. CANADIAN WHISKY ONLY O.F.C. IS GUARANTEED OVER 6 YEARS OLD! \ HIK \1> Among Canadian whiskies, only O.F.C. tells you its exact age by placing a Certificate of Age on every bottle. Every drop has the same unchanging taste and quality. Yet O.F.C. costs no more than other Canadian whiskies. SchmkyM' Any bottle that says ^Schcnlc says SCHENLEY INTERNATIONAL CORP., NEW YORK, N Y. For Business .. For Pleasure Fnr a WnrIH nf ^prvirp YOU CAN COUNT ON AMERICAN EXPRESS Here are the world-wide, world-wise service, offered by American Express . 397 offices in 35 nations always ready to serve you completely, expertly, whatever your needs for business or pleasure. TRAVELERS CHEQUES MONEY ORDERS The best-known, most widely accepted cheques in the world! Pay bills and transmit funds American Express Travelers with convenient, economical Cheques are 100% safe—immediate American Express Money refund if lost or stolen. You can Orders... available through¬ buy them at BANKS, Railway out the U. S. at neighborhood Express and Western Union offices. stores, Railway Express and Western Union offices. TRAVEL SERVICES The trained and experienced OTHER FINANCIAL SERVICES staff of American Express Swift... convenient and dependable, will provide air or steamship other world-wide American Express tickets... hotel reservations... financial services include: foreign uniformed interpreters, and remittances, mail and cable transfer plan independent trips or of funds, and the purchase and escorted tours. SHIPPING SERVICES American Express offers t complete facilities to handle personal and household effects shipments, also the entire operation of import or export forwarding, including customs clearances and marine insurance. -

June 1-15, 1969

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Presidential Helicopter Flights 6/3/1969 A 2 Manifest Passenger Manifest – Air Force One 6/3/1969 A 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest 6/6/1969 A 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest 6/7/1969 A 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest from n.d. A Hickam AFB, Honolulu, Hawaii 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest 6/8/1969 A 7 Manifest Passenger Manifest – Air Force One from n.d. A Honolulu, Hawaii to Midway COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-3 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary June 1, 1969 – June 15, 1969 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------