The Story of Sambhar by Padmini Natarajan — Archive.Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Main Items: Appam: Pittu: Dosa: Naan Bread: Kothu Parotta

Main Items: Idiyappam Idly Chappathi Idiyappa Kothu Appam: Plain Appam Paal Appam Egg Appam Pittu: Plain Pittu Kuzhal Pittu Keerai Pittu Veg Pittu Kothu Egg Pittu Kothu Dosa: Plain Dosa Butter Plain Dosa Onion Masala Egg Dosa Masala Dosa Egg Cheese Dosa Onion Dosa Nutella Dosa Ghee Roast Plain Roast Naan Bread: Plain Naan Garlic Naan Cheese Naan Garlic Cheese Naan Kothu Parotta: Veg Kothu Parotta Egg Kothu Parotta Chicken Kothu Parotta Mutton Kothu Parotta Beef Kothu Parotta Fish Kothu Parotta Prawn Kothu Parotta RICE: Plain Rice Coconut Rice Lemon Rice Sambar Rice Tamarind Rice Curd Rice Tomato Rice Briyani: Veg Briyani Chicken Briyani Mutton Briyani Fish Briyani Prawn Briyani Fried Rice: Veg Fried Rice Chicken Fried Rice Seafood Fried Rice Mixed Meat Fried Rice Egg Fried Rice Fried Noodles: Veg Fried Noodles Chicken Fried Noodles Seafood Fried Noodles Mixed Meat Fried Noodles Egg Fried Noodles Parotta: Plain Parotta Egg Parotta EggCheese Parotta Chilli Parotta Nutella Parotta Live Item: Varieties of Appam Varieties of Parotta Varieties of Pittu Varieties of Dosa Mutton(Bone Boneless ▭): Mutton Curry (Srilankan & Indian Style) ▭ Mutton Devil ▭ Mutton Rasam ▭ Mutton Kuruma ▭ Mutton Varuval ▭ Pepper Mutton ▭ Chicken(Bone Boneless ▭): Chicken Curry (Srilankan & Indian Style) ▭ Chicken 65 ▭ Pepper Chicken ▭ Chicken Devil ▭ Chicken Tikka ▭ Butter Chicken ▭ Chicken Rasam ▭ Chicken Kuruma ▭ Chicken Varuval ▭ Chilli Chicken ▭ Chicken Lollipop Chicken Drumstick -

View Newsletter

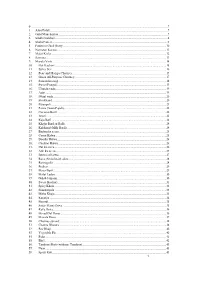

0. ..........................................................................................................................................................................................7 1. Aloo Palak.................................................................................................................................................................7 2. Gobi Manchurian.....................................................................................................................................................7 3. Sindhi Saibhaji..........................................................................................................................................................8 4. Shahi Paneer .............................................................................................................................................................9 5. Potato in Curd Gravy.............................................................................................................................................10 6. Navratan Korma .....................................................................................................................................................11 7. Malai Kofta.............................................................................................................................................................12 8. Samosa.....................................................................................................................................................................13 -

Rasam Recipe | Tomato Rasam | Thakkali Rasam with Dal

Rasam Recipe | Tomato Rasam | Thakkali Rasam with dal Rasam is a south Indian Soup, prepared with tomato, dal and various aromatic spices. To me, they are the comforting food next to idly. They are mildly tangy, watery in consistency and a medley of fresh aroma and flavors. South Indian meals are incomplete without rasam. Many family in south India makes rasam everyday. They are the soul food to many homes. Coming to the recipe, everyone makes rasam in a different way and this is my version of tomato rasam recipe, without tamarind, here I added toor dal in additional to tomatoes, to get a nice taste and also for protein. The one thing I like most in rasam is the lovely flavor and fresh aroma which comes from coriander leaves, asafoetida and garlic. Making of rasam is easy and can be made fast, they are good for digestion as it has lot of spices in it. Also it is a good food for people with fever and cough. Tomato rasam can be served with potato fry or vegetable fry. I had it with butterbeans poriyal. Ingredients 4 Tomatoes 3 Tbsp of Toor Dal Salt to taste Water as needed To Make a Rasam Powder 1 Tsp of Whole Black Pepper 2 Tsp of Whole Cumin 2 Tsp of Coriander Powder 3 Garlic Cloves, Big To Temper 2 Tsp of Oil 1 Big Dried Red Chilly 1 Tsp of Mustard Seeds 1 Tsp of Urad Dal 1/8 Tsp of Fenugreek Seeds Pinch of Asafoetida Few Curry Leaves 1/4 Tsp of Turmeric Powder To Garnish Handful of Coriander leaves, Finely Chopped Method Soak the dal in water for 15-20 minutes, drain the water and wash it. -

Paruppu Urundai Kuzhambu Recipe

PARUPPU URUNDAI KUZHAMBU RECIPE Paruppu urundai kuzhambu recipe is a traditional kulambu recipe from Tamilnadu. Lentil Balls are made from soaked toor and chenna dal, then it was cooked in gravy containing onions, tomatoes, tamarind juice and spices. This is my mom’s recipe, she is a great cook because whatever she makes at home, it turns out good and tasty..I really miss all my mom’s recipes. This paruppu urundai kuzhambu recipe is very healthy, delicious and super nutritious but a lengthy process . Just give it a try and let me know the feedback. Ingredients for paruppu urundai kuzhambu recipe To Make a Lentil Balls ( Paruppu Urundai) 1 Medium Size Onion, Finely Chopped 3 Garlic Cloves, Finely Chopped 1/2 Tsp of Fennel ( Sombhu ) 1/2 Tsp of Cumin ( Jeeragam) 1 Tbsp of Coconut Flakes Few Curry Leaves, Finely Chopped Few Coriander Leaves, Finely Chopped To Grind 1/4 Cup of Toor Dal ( Thuvaram Paruppu ) 1/4 Cup of Chenna Dal ( Kadalai Paruppu) 3 Red Chillies Pinch of Asafoetida Salt to Taste To Make a Gravy To Saute & Grind 10 Small Onions, Finely Chopped 2 Medium Size Tomatoes, Finely Chopped < 1/4 Tsp of Fennel ( Sombhu) < 1/4 Tsp of Cumin ( Jeeragam) 3 Tsp of Sambhar Powder ( Heaping) 2 Tsp of Oil To Temper 3 Tsp of Oil 1 Tsp of Mustard 1 Tsp of Urad Dal Few Curry Leaves Other Ingredients Gooseberry size of Tamarind Pinch of Jaggery or Sugar Method paruppu– urundai kuzhambu recipe To Make Lentil Balls Soak toor and chenna dal for 2 hrs. -

Tomato Pickle Recipe / Thakkali Oorugai (Tamilnadu Style),Roja Poo Kashayam / Rose Petal Tea / Herbal Drink for Sore Throat,Saiv

Tomato Pickle Recipe / Thakkali Oorugai (Tamilnadu Style) Tomato Pickle Recipe / Thakkali Oorugai is our family favourite dish. My mom makes it often and refrigerate it in a big jar. Every household has its own pickle recipe and this is my mom’s signature recipe and my dad is a huge fan for this pickle. For every meal, he have it without fail as side dish for tiffin items or with rice. This thakkali orrugai has got sweet, tangy and spicy note and are spiced with mustard, fenugreek, asafoetida, garlic and red chilly. It has no preservatives or colouring agents as it is homemade so good for health. It can be served with idli, dosa, pongal, rice, roti, poori and paniyaram. You can even spread it in sandwiches and take it out for picnic . This tomato pickle was made in my mom’s kitchen, I just clicked it for blog sake. I love to eat it with hot steamed white rice with some ghee on top. Try it in your home, you will love it for sure. Check other pickle recipes in my blog – Lemon Pickle, Mango Pickle, garlic pickle, Vadu mango pickle How to make Tomato pickle recipe with step by step pictures Preparation Cooking Procedure Tomato Pickle Recipe / Thakkali Oorugai (Tamilnadu Style) Save Print Prep time 20 mins Cook time 1 hour 30 mins Total time 1 hour 50 mins Tomato Pickle Recipe / Thakkali Oorugai (Tamilnadu style) is a favourite condiment to me. This is my mom’s recipe and it can be served with idli, dosa, pongal, rice, roti, poori and paniyaram. -

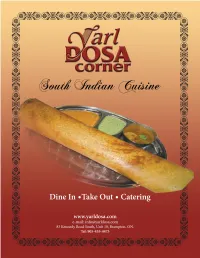

Dosa-Corner-Menu2020.Pdf

Appetizers Idly (2Pcs) 4 99 Steamed rice and lentil served with chutney and sambar Methu Vada (2Pcs) 4 99 Fried lentil doughnut served with chutney and sambar Rasa Vada (2pcs) 6 99 Methu vada dipped in spicy rasam Sambar Vada (2pcs) 5 99 Methu vada dipped in hot sambar served with chutneyv Dahi Vada (2pcs) 6 99 Methu vada dipped in spicy yougurt Rasam Idly (2pcs) 6 99 Idly dipped in rasam served with chutney Sambar Idly (2pcs) 5 99 Idly dipped in hot sambar served with chutney Dahi Idly (2pcs) 6 99 Steamed rice and lentil cakes dipped in seasoned yourgurt Idly Vada Combo 7 99 2 Idlies and 1 vada or 1 Idly and 2 Vadas Rava Upma 6 99 Soup Tomato Soup 4 99 Rasam 4 99 Breads Kerala Parota(2) 10 99 Served with veg Curry Extra Parota 1 99 Set Dosa Dosas 5 99 Set of two soft dosas Sada Dosa 7 99 Thin rice crepe Masala Dosa 8 99 Thin rice crepe filled with spiced potato Mysore Sada Dosa 8 99 Spicy chutney smeared inside sada dosa Mysore Masala Dosa 9 99 Spicy chutney smeared inside masala dosa Paper Dosa 9 99 Large thin paper crisp rice crepe Paper Masala Dosa 10 99 Paper dosa stuffed with spiced potatoes and onion Onion Dosa 7 99 Sada dosa smeared with raw onions Onion Masala Dosa 9 99 Masala dosa smeared with raw onions Garlic Masala Dosa 9 99 Dosa smeared with garlic chutney Chilli Garlic Masala Dosa 10 99 Dosa smeared with garlic spicy chutney Chilli Onion Garlic Masala Dosa 11 99 Masala dosa smeared with raw onion, chilli and garlic Chilli Cheese Dosa 11 99 Dosa smeared with spicy chutney, cheddar and mozzarella cheese Cheese Dosa 10 99 -

TBLA Dine in Menu Feb21.Pdf

Signature Dishes A1 APOLO FISH HEAD CURRY Fresh red snapper fish head submerged in a robust curry cooked with more than 20 spices & assorted vegetables including okra, tomatoes and eggplants SMALL (S) 24.00 MEDIUM (M) 28.00 LARGE (L) 32.00 Starters S1 VEGETABLE SAMOSAS 6.90 Deep fried pastry with savoury filling of potatoes and vegetables S2 CRISPY ONION PAKORAS 6.90 Deep fried batter snack made of besan flour, spices and onions S3 GOBI 65 10.90 Deep fried marinated cauliflower florets with Indian spices S4 FISH FINGERS 12.90 Seasoned finger-sized fish fillet fried gently to a crispy taste S1 VEGETABLE SAMOSAS S5 CHICKEN LOLLIPOP 12.90 Deep fried chicken winglets marinated with Indian spices S3 GOBI 65 S5 CHICKEN LOLLIPOP Tandoori T1 TANDOORI CHICKEN (HALF) 14.90 Four chunks of chicken marinated with Indian spices and grilled in tandoor pot T2 TANDOORI CHICKEN (FULL) 26.90 Eight chunks of chicken marinated with Indian spices and grilled in tandoor pot T3 TANDOORI PRAWN 19.90 Marinated prawns grilled gently in tandoor pot T4 TANDOORI NON VEG PLATTER 36.90 Assorted tandoori non veg dishes served in one platter (Chicken tikka, fish tikka, prawn tikka, sheekh kebab, Murgh malai kebab and tandoori chicken) T5 TANDOORI VEG PLATTER 26.90 Assorted tandoori vegetarian dishes served in one platter T4 TANDOORI NON VEG PLATTER T6 MURGH MALAI KEBAB 15.90 Marinated boneless chicken cubes mixed with cream and cashew nut, gently grilled in tandoor pot T7 VEG SEEKH KEBAB 12.90 Marinated vegetarian dishes served in tandoor pot T8 MUTTON SHEEKH KEBAB 18.90 Minced -

Panther Press the Digital Newspaper

Tuesday, Issue June 14th, 8 2021 Panther Press The Digital Newspaper Don’t Squish! Rethink! - Protesting the Killing of Bugs ------------ Momina Khuram Have you ever killed a bug? Everyone probably has done this, but today I am objecting to killing bugs. “Why?” you may ask. Imagine all the bugs in the world disappeared. There would be no more adventure. No chirping birds. No buzzing bees. It would be sad, boring, and silent outside. There are so many species of bugs in the world. Each one is unique in its skills. The more we learn about bugs the more we learn about our earth. Just like humans and other animals, bugs deserve a life too. I believe you should never kill bugs. I believe that you should not kill insects when they are outside. Bugs belong outside. They have families or colonies in which they are a vital part. You do not want to destroy these systems by taking out one of the workers. Picture caption: Periodical cicada (Magicicada sp.). Photo: Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources - Forestry, Insects are not insignificant for people. Bugwood.org Bugs actually benefit humans as well. They pollinate crops that we need for food and pollinate beautiful flowers that we enjoy viewing. They also act as sanitation workers cleaning up our wastes. Despite their sometimes-creepy appearance, they are important to our environment. If you feel that you are in danger of being bitten or stung by an insect, walk or run away instead of killing it. Sometimes, people feel unsafe near bugs, so they decide to kill them immediately. -

Eat Like a Local: Madurai

eat out eateat away out chef special chefMadurai special EASY MENU FOR 4 eat like a local T Kothu parotta T Kaara kuzhambu T Vendakkai poriyal T Madurai vegetable biryani MADURAI T Jigarthanda Fondly called the food capital of Tamil Nadu, the temple city of Madurai welcomes visitors with its varied cuisine — from Chettinad specialities to Ceylon parathas Words and photographs CHARUKESI RAMADURAI Food photographs JOY MANAVATH adurai has been a beverage — the jigarthanda. Literally Kothu parotta city of commerce, meaning ‘heart cooler’, it is a tall glass Serves 2 n 20 minutes + resting with trade relations of sarsaparilla syrup (locally known n EASY extending to the as nannari), almond jelly (also called Kothu parotta being MRomans and Greeks. Arab merchants badam pisin), sugar, milk and ice cream, A popular roadside snack, this made on a griddle and Sufi saints also made their way with a garnish of almonds and pistas. recipe can be made using leftover to the city to trade with the Pandya Madurai is inordinately fond of parathas. You can experiment with kings since 900 AD. Closer to home, fried snacks, with shops proudly Bharathi Mohan both vegetarian and non-vegetarian the local Chettiar community traded carrying names like ‘Tamizhaga Ennai is the head chef options. extensively with Ceylon (now Sri Palagaram’ (Tamil Nadu Oil Snacks). at Heritage A lady weaving a garland with Lanka), Singapore and Malaysia. And desserts are considered incomplete Madurai. He maida 1 cup malligaipoo (jasmine) Moreover, silk weavers and merchants unless they come dripping with ghee, hails from milk 1/2 cup from Saurashtra in Gujarat have made such as the gooey Thirunelveli halwa at Trichy in Tamil salt to taste Vendakkai poriyal Madurai home for several centuries Prema Vilas Lala Sweet Shop. -

Eating Lolly

Eating Lolly Corrie Hosking MA BA (Hons) Department of English University of Adelaide September 2004 Abstract There is an overwhelming archive of literature written on so-called 'eating disorders' and the social and cultural contexts that shape these'conditions'. Theories framed by psychiatry, feminism, psychoanalysis and sociology have each presented insights and specific understandings of the causes of the 'disorders' anorexia and bulimia nervosa and the 'type' of people they affect. Although such theories are often presented as objective 'truths', their meanings aÍe constructed in a cultural context. They are often contradictory, frequently ambiguous and regularly paradoxical. Despite the wealth of research being done on 'eating disorders', we are still most likely to read particular and specific explanations that are mostly informed by the psycho-medical discourses, that are preoccupied with anorexia over other forms of eating distress and that neglect the thoughts, theories, language and voices of women with lived experience. My research explores the opposing cultural constructions of anorexia and bulimia against women's personal naratives of life with bulimia. My specific interest in bulimia contests the focus on anorexia in the medical, academic and popular spheres. I address this imbalance, and speculate on why there is such a preoccupation with anorexia over other eating issues in our culture. I believe that this is not a coincidence, for there are deep seated, cultural and historical reasons why our culture demonstrates a fascination with, even admiration for, anorexia. Research into the socio-cultural construction of 'eating disorders' provided a rich and complex resource for developing my novel: Eating Lolly. -

Indian Vegetarian Recipes We Are Vegetarian Specialist

-61- Indian Vegetarian recipes We are Vegetarian Specialist SWEETS D) Bengali(Milk) Items A) Badam Items Anar Kali - Pick-up Badam Kathli Kashmiri Apple Badam Kesar Kathli Champa Kali Badam Dry Fruit Kathli Cherry Malai Badam Anjeer Kathli Pink Malai Chop Badam Pista Kathli Bengali Kalakund - very soft Badam Biscuit Bengali Mix Plater Pick Up Badam Pista Casetta Cham Cham Badam Anjeer Roll Malai Singada Badam Pista Roll Kesar Vati Badam Fruit Dai Kadame Kheer Badam Tiranga Roll Sandesh Aam Badam Rakhi BenGali Kalkund (Sugar Free) Badam Pizza Cham-Cham [White] Badam Kattori Kamal Bhog Badam Mango Malai Sandwich Badam Jilebi Sandesh Illaychi Badam Anarkali Gulab Bhog Badam Water Melon Angoori Badam Jab – Jab Phool Khile Nawaratna Angoori Badam Halwa Tawa Mithai (Hot – Cool) Badam Cake ( Chaki) Basundi Badam Seera Rasamalai Badam Burfy Rasamalai Rose Flower Rasagulla B) Cashews Items Butter Rasugulla Kaju Kathli Aagra Basundi Kaju Roll E) Halwa Items Kaju Pista Roll Kaju Pista Cake Carrot Halwa Kaju Anarkali Kasi Halwa Kaju Water Melon Ashoka Halwa Kaju Apple Moong Dhall Halwa Kaju Square Double Takker Badam Halwa Kaju Dai Aagrot Halwa Kaju Halwa Surakkai Halwa Kaju Biscuit Beetroot Halwa Kaju Casetta Bombay Halwa Kaju Seera Gajjar Halwa Kaju Kas Kas Roll Maskoth Halwa Dry Fruit Halwa C) Maida Items Pancharatna Halwa Jalebi Tawa Halwa Malpoova Sada Velleri halwa Kaju Halwa Rabadi Malpoova Diamond Cakes Pista Halwa Mawa Kachodi Surya Kala Chandra Kala Badhusa -62- F) Khowa Items K) Payasam Items Gulab Jamun Semiya Payasam Kala Jamun Milk -

Verkadalai Kuzhambu Recipe / Peanut Curry

Verkadalai Kuzhambu Recipe / Peanut Curry Peanut is a legume that can be used to make lot of recipes like peanut curry, sides with vegetables, peanut noodles, peanut rice, peanut chutney snacks like peanut sundal, peanut chaat, desserts like peanut ladoo, peanut fudge etc. Verkadalai kuzhambu Recipe / Peanut Curry is a traditional south Indian dish, it tastes great with hot steamed rice and ghee. This tangy and spicy kuzhambu is prepared using raw peanuts, onion, tamarind, and spices, served with rice, creamy spinach and appalam. For a change, I added soy sauce to give a twist to traditional kuzhambu recipe. You can also make kuzhambu with vegetables like brinjal, drumstick, bittergourd etc. If you are looking for easy and healthy kuzhambu recipe, then do try this dish. Also check my other kuzhambu recipe Manathakali Kai Kara Kuzhambu Vendhaya Kulambu Soya Chunks Mushroom Curry Milagu Kuzhambu / Pepper Gravy Creamy Spinach Mochai Murungakai Kulambu Chickpeas Curry Vendakkai Puli Pachadi Kerala Avial / Aviyal Mushroom Spinach Gravy Allepey Mixed vegetable curry Beetroot Sambhar Green Onion Sambar Arachu Vitta Sambar Potato Masala for Poori Vendakkai Vatha Kulambu Tomato Rasam Kollu Rasam Thuthuvalai Rasam Paruppu Urundai Kulambhu Thatta Payir(Karamani) Kara Kulambu Tirunelveli Sodhi and Ginger Chutney Kerala Kadala Curry Ingredients for Verkadalai kuzhambu Recipe Preparation Time : 10 mins Cooking Time: 30 mins Serves: 3 • 3/4 Cup of Raw Peanuts • 1 Big Red Onion, Finely Chopped • 10 Garlic Cloves • Small Gooseberry Size of Tamarind • 3 Tsp of Sambhar Powder / Kuzhambu Powder • 1 Tsp of Coriander Powder • 1 Tsp of Soy Sauce • Salt to taste • Pinch of Asafoetida • Pinch of Jaggery • 1 Tsp of Rice Flour To Temper • 1 Tbsp of Gingelly Oil • 1 Red Chilly • 1/8 Tsp of Fenugreek Seeds • 1 Tsp of Mustard Seeds • 1 Tsp of Urad Dal • Few Curry Leaves Method for Verkadalai Kuzhambu Recipe Preparation: • Soak the raw peanuts in water for overnight.