Research Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FUS-Mediated Functional Neuromodulation for Neurophysiologic Assessment in a Large Animal Model Wonhye Lee1*, Hyungmin Kim2, Stephanie D

Lee et al. Journal of Therapeutic Ultrasound 2015, 3(Suppl 1):O23 http://www.jtultrasound.com/content/3/S1/O23 ORALPRESENTATION Open Access FUS-mediated functional neuromodulation for neurophysiologic assessment in a large animal model Wonhye Lee1*, Hyungmin Kim2, Stephanie D. Lee1, Michael Y. Park1, Seung-Schik Yoo1 From Current and Future Applications of Focused Ultrasound 2014. 4th International Symposium Washington, D.C, USA. 12-16 October 2014 Background/introduction element FUS transducer with radius-of-curvature of Focused ultrasound (FUS) is gaining momentum as a 7 cm) was transcranially delivered to the unilateral sen- new modality of non-invasive neuromodulation of regio- sorimotor cortex, the optic radiation (WM tract) as well as nal brain activity, with both stimulatory and suppressive the visual cortex. An acoustic intensity of 1.4–15.5 W/cm2 potentials. The utilization of the method has largely Isppa, tone-burst-duration of 1 ms, pulse-repetition fre- been demonstrated in small animals. Considering the quency of 500 Hz (i.e. duty cycle of 50%), sonication dura- small size of the acoustic focus, having a diameter of tion of 300 ms, were used for the stimulation. A batch of only a few millimeters, FUS insonification to a larger continuous sonication ranging from 50 to 150 ms in dura- animal’s brain is conducive to examining the region- tion were also given. Evoked electromyogram responses specific neuromodulatory effects on discrete anatomical from the hind legs and electroencephalogram from the Fz areas, including the white matter (WM) tracts. The and Oz-equivalent sites were measured. The histology of study involving large animals would also establish preli- the extracted brain tissue (within one week and 2 months minary safety data prior to its translational research in post-sonication) was obtained. -

Visual and Electrosensory Circuits of the Diencephalon in Mormyrids: an Evolutionary Perspective

THE JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE NEUROLOGY 297:537-552 (1990) Visual and Electrosensory Circuits of the Diencephalon in Mormyrids: An Evolutionary Perspective MARIO F. WULLIMANN AND R. GLENN NORTHCUTT Georg-August-Universitat,Zentrum Anatomie, 3400 Gottingen, Federal Republic of Germany (M.F.W.); University of California, San Diego, and Department of Neurosciences A-001, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California 92093 (R.G.N.) ABSTRACT Mormyrids are one of two groups of teleost fishes known to have evolved electroreception, and the concomitant neuroanatomical changes have confounded the interpretation of many of their brain areas in a comparative context, e.g., the diencephalon, where different sensory systems are processed and relayed. Recently, cerebellar and retinal connections of the diencephalon in mormyrids were reported. The present study reports on the telencephalic and tectal connections, specifically in Gnathonemus petersii, as these data are critical for an accurate interpretation of diencephalic nuclei in teleosts. Injections of horseradish peroxidase into the telencephalon retrogradely labeled neurons ipsilaterally in various thalamic, preglomer- ular, and tuberal nuclei, the nucleus of the locus coeruleus (also contralaterally), the superior raphe, and portions of the nucleus lateralis valvulae. Telencephalic injections anterogradely labeled the dorsal preglomerular and the dorsal tegmental nuclei bilaterally. Injections into the optic tectum retrogradely labeled neurons bilaterally in the central zone of area dorsalis telencephali and ipsilaterally in the torus longitudinalis, various thalamic, pretectal, and tegmental nuclei, some nuclei in the torus semicircularis, the nucleus of the locus coeruleus, the nucleus isthmi and the superior reticular formation, basal cells in the ipsilateral valvula cerebelli, and eurydendroid cells in the contralateral lobe C4 of the corpus cerebelli. -

Embryology, Anatomy, and Physiology of the Afferent Visual Pathway

CHAPTER 1 Embryology, Anatomy, and Physiology of the Afferent Visual Pathway Joseph F. Rizzo III RETINA Physiology Embryology of the Eye and Retina Blood Supply Basic Anatomy and Physiology POSTGENICULATE VISUAL SENSORY PATHWAYS Overview of Retinal Outflow: Parallel Pathways Embryology OPTIC NERVE Anatomy of the Optic Radiations Embryology Blood Supply General Anatomy CORTICAL VISUAL AREAS Optic Nerve Blood Supply Cortical Area V1 Optic Nerve Sheaths Cortical Area V2 Optic Nerve Axons Cortical Areas V3 and V3A OPTIC CHIASM Dorsal and Ventral Visual Streams Embryology Cortical Area V5 Gross Anatomy of the Chiasm and Perichiasmal Region Cortical Area V4 Organization of Nerve Fibers within the Optic Chiasm Area TE Blood Supply Cortical Area V6 OPTIC TRACT OTHER CEREBRAL AREASCONTRIBUTING TO VISUAL LATERAL GENICULATE NUCLEUSPERCEPTION Anatomic and Functional Organization The brain devotes more cells and connections to vision lular, magnocellular, and koniocellular pathways—each of than any other sense or motor function. This chapter presents which contributes to visual processing at the primary visual an overview of the development, anatomy, and physiology cortex. Beyond the primary visual cortex, two streams of of this extremely complex but fascinating system. Of neces- information flow develop: the dorsal stream, primarily for sity, the subject matter is greatly abridged, although special detection of where objects are and for motion perception, attention is given to principles that relate to clinical neuro- and the ventral stream, primarily for detection of what ophthalmology. objects are (including their color, depth, and form). At Light initiates a cascade of cellular responses in the retina every level of the visual system, however, information that begins as a slow, graded response of the photoreceptors among these ‘‘parallel’’ pathways is shared by intercellular, and transforms into a volley of coordinated action potentials thalamic-cortical, and intercortical connections. -

Anatomy and Physiology of the Afferent Visual System

Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 102 (3rd series) Neuro-ophthalmology C. Kennard and R.J. Leigh, Editors # 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved Chapter 1 Anatomy and physiology of the afferent visual system SASHANK PRASAD 1* AND STEVEN L. GALETTA 2 1Division of Neuro-ophthalmology, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Womens Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA 2Neuro-ophthalmology Division, Department of Neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA INTRODUCTION light without distortion (Maurice, 1970). The tear–air interface and cornea contribute more to the focusing Visual processing poses an enormous computational of light than the lens does; unlike the lens, however, the challenge for the brain, which has evolved highly focusing power of the cornea is fixed. The ciliary mus- organized and efficient neural systems to meet these cles dynamically adjust the shape of the lens in order demands. In primates, approximately 55% of the cortex to focus light optimally from varying distances upon is specialized for visual processing (compared to 3% for the retina (accommodation). The total amount of light auditory processing and 11% for somatosensory pro- reaching the retina is controlled by regulation of the cessing) (Felleman and Van Essen, 1991). Over the past pupil aperture. Ultimately, the visual image becomes several decades there has been an explosion in scientific projected upside-down and backwards on to the retina understanding of these complex pathways and net- (Fishman, 1973). works. Detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the visual The majority of the blood supply to structures of the system, in combination with skilled examination, allows eye arrives via the ophthalmic artery, which is the first precise localization of neuropathological processes. -

Tracing in Vivo the Dorsal Loop of the Optic Radiation: Convergent Perspectives from Tractography and Electrophysiology Compared to a Neuroanatomical Ground Truth

Tracing in Vivo the Dorsal Loop of the Optic Radiation: Convergent Perspectives From Tractography and Electrophysiology Compared to a Neuroanatomical Ground Truth. Michele Rizzi ( [email protected] ) ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda Centro Munari Chirurgia dell'Epilessia e del Parkinson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7936-6536 Ivana Sartori ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda Centro Munari Chirurgia dell'Epilessia e del Parkinson Maria Del Vecchio National Research Council: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Flavia Maria Zauli University of Milan Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences Luigi Sacco: Universita degli Studi di Milano Dipartimento di Scienze Biomediche e Cliniche Luigi Sacco Luca Berta ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda: Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda Domenico Lizio Niguarda Ca Granda Hospital: Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda Alessandro De Benedictis Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù: Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesu Silvio Sarubbo Presidio Ospedaliero Santa Chiara: Ospedale di Trento Valeria Mariani ASST dei Sette Laghi: Aziende Socio Sanitarie Territoriale dei Sette Laghi Khalid Al-Orabi ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda Centro Munari Chirurgia dell'Epilessia e del Parkinson Pietro Avanzini National Research Council: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Research Article Keywords: white matter, Klinger dissection, visual evoked potential, inter-trial coherence, SEEG, visual system Page 1/25 Posted Date: June 10th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-589114/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/25 Abstract The temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) is a cortical area contributing to a multiplicity of visual, language- related and cognitive functions. -

1. Lateral View of Lobes in Left Hemisphere TOPOGRAPHY

TOPOGRAPHY T1 Division of Cerebral Cortex into Lobes 1. Lateral View of Lobes in Left Hemisphere 2. Medial View of Lobes in Right Hemisphere PARIETAL PARIETAL LIMBIC FRONTAL FRONTAL INSULAR: buried OCCIPITAL OCCIPITAL in lateral fissure TEMPORAL TEMPORAL 3. Dorsal View of Lobes 4. Ventral View of Lobes PARIETAL TEMPORAL LIMBIC FRONTAL OCCIPITAL FRONTAL OCCIPITAL Comment: The cerebral lobes are arbitrary divisions of the cerebrum, taking their names, for the most part, from overlying bones. They are not functional subdivisions of the brain, but serve as a reference for locating specific functions within them. The anterior (rostral) end of the frontal lobe is referred to as the frontal pole. Similarly, the anterior end of the temporal lobe is the temporal pole, and the posterior end of the occipital lobe the occipital pole. TOPOGRAPHY T2 central sulcus central sulcus parietal frontal occipital lateral temporal lateral sulcus sulcus SUMMARY CARTOON: LOBES SUMMARY CARTOON: GYRI Lateral View of Left Hemisphere central sulcus postcentral superior parietal superior precentral gyrus gyrus lobule frontal intraparietal sulcus gyrus inferior parietal lobule: supramarginal and angular gyri middle frontal parieto-occipital sulcus gyrus incision for close-up below OP T preoccipital O notch inferior frontal cerebellum gyrus: O-orbital lateral T-triangular sulcus superior, middle and inferior temporal gyri OP-opercular Lateral View of Insula central sulcus cut surface corresponding to incision in above figure insula superior temporal gyrus Comment: Insula (insular gyri) exposed by removal of overlying opercula (“lids” of frontal and parietal cortex). TOPOGRAPHY T3 Language sites and arcuate fasciculus. MRI reconstruction from a volunteer. central sulcus supramarginal site (posterior Wernicke’s) Language sites (squares) approximated from electrical stimulation sites in patients undergoing operations for epilepsy or tumor removal (Ojeman and Berger). -

Analysis of the Relationship of Optic Radiations to Lateral Ventricle: a Cadaveric Study

Original Article Fiber dissection of the visual pathways: Analysis of the relationship of optic radiations to lateral ventricle: A cadaveric study Vikrant B. Pujari, Hiryuki Jimbo, Nitin Dange, Abhidha Shah, Sukhdeep Singh, Atul Goel Department of Neurosurgery, King Edward Memorial Hospital and Seth G.S. Medical College, Parel, Mumbai, India Objective: Using a Þ ber-dissection technique, our aim is to dissection of the brain in general and on optic tracts in [1-5] study the Þ ber bundles of the optic radiation. We focused particular. The surgical approach to temporal horn on the course, the length, anatomical relations with lateral and mediobasal structures can be categorized into three [6] ventricle and the relevance of these Þ nding during surgery in main groups: lateral, subtemporal and transsylvian. the region. Materials and Methods: Five previously frozen These approaches have their own merits and demerits and formalin-Þ xed cadaveric human brains were used. The based on location of language and visual processing dissection was done using the operating microscope. Fiber areas in the lateral temporal lobe and underlying the dissection techniques described by Klingler were adopted. fibers including the optic radiations. The primary dissection tools were handmade, thin, and In this presentation, we attempt to evaluate the wooden and curved metallic spatulas with tips of various anatomical relationships of optic radiations and sizes. Lateral and inferior temporal approaches were made advantage of approach to temporal horn through safe and the optic Þ ber tracts were dissected. Results: Resections area of lateral wall of temporal horn. that extend through the roof of the temporal horn more than 30 mm behind the temporal pole cross the Meyer’s loop. -

Activation of the Hypothalamic Feeding Centre Upon Visual Prey Detection

ARTICLE Received 26 Oct 2015 | Accepted 21 Feb 2017 | Published 20 Apr 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15029 OPEN Activation of the hypothalamic feeding centre upon visual prey detection Akira Muto1, Pradeep Lal1,w, Deepak Ailani1, Gembu Abe1,w, Mari Itoh1 & Koichi Kawakami1 The visual system plays a major role in food/prey recognition in diurnal animals, and food intake is regulated by the hypothalamus. However, whether and how visual information about prey is conveyed to the hypothalamic feeding centre is largely unknown. Here we perform real-time imaging of neuronal activity in freely behaving or constrained zebrafish larvae and demonstrate that prey or prey-like visual stimuli activate the hypothalamic feeding centre. Furthermore, we identify prey detector neurons in the pretectal area that project to the hypothalamic feeding centre. Ablation of the pretectum completely abolishes prey capture behaviour and neurotoxin expression in the hypothalamic area also reduces feeding. Taken together, these results suggest that the pretecto-hypothalamic pathway plays a crucial role in conveying visual information to the feeding centre. Thus, this pathway possibly converts visual food detection into feeding motivation in zebrafish. 1 Division of Molecular and Developmental Biology, National Institute of Genetics, Department of Genetics, SOKENDAI (The Graduate University for Advanced Studies), Yata 1111, Mishima, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan. w Present addresses: The Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience/Centre for Neural Computation, NTNU Faculty of Medicine, Olav Kyrres g 9, Trondheim 7030, Norway (P.L.); Department of Developmental Biology and Neurosciences, Graduate School of Life Sciences, Tohoku University, Katahira 2-1-1 Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi 980-8577, Japan (G.A.). -

1 a Taxonomy of the Brain's White Matter

A taxonomy of the brain’s white matter: Twenty-one major tracts for the twenty-first century Daniel N. Bullock1, Elena A. Hayday2, Mark D. Grier2, *Wei Tang1,3, *Franco Pestilli4, *Sarah R. Heilbronner2 *These authors share senior author contribution 1. Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Program in Neuroscience, Indiana University Bloomington, Bloomington, IN USA 47405 2. Department of Neuroscience, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN USA 55455 3. Department of Computer Science, Indiana University Bloomington, Bloomington, IN USA 47408 4. Department of Psychology, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX USA 78712 Correspondence: Sarah R. Heilbronner, PhD 2-164 Jackson Hall 321 Church St SE Minneapolis, MN 55455 772-285-7021 [email protected] Acknowledgements: SRH was supported by NIH R01MH118257 (SRH); MDG was supported by NIDA T32DA007234 to P. Mermelstein (UMN); DNB was supported by NIMH 5T32MH103213-05 to W. Hetrick (IU); FP was supported by NSF IIS-1636893, NSF BCS-1734853, NSF IIS-1912270, NIH NIBIB 1-R01-EB029272- 01, and a Microsoft Investigator Fellowship. Conflicts: SRH has received teaching fees from Medtronic, Inc. Remaining authors have no conflicts to disclose. 1 Abstract The functional and computational properties of brain areas are determined, in large part, by their connectivity profiles. Advances in neuroimaging and network neuroscience allow us to characterize the human brain noninvasively and in vivo, but a comprehensive understanding of the human brain demands an account of the anatomy of brain connections. Long-range anatomical connections are instantiated by white matter and organized into tracts. Here, we aim to characterize the connections, morphology, traversal, and functions of the major white matter tracts in the brain. -

Getting Signals Into the Brain: Visual Prosthetics Through Thalamic Microstimulation

Neurosurg Focus 27 (1):E6, 2009 Getting signals into the brain: visual prosthetics through thalamic microstimulation JOHN S. PEZARI S , PH.D., AN D EMA D N. ES KAN D AR , M.D. Department of Neurosurgery, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts Common causes of blindness are diseases that affect the ocular structures, such as glaucoma, retinitis pigmen- tosa, and macular degeneration, rendering the eyes no longer sensitive to light. The visual pathway, however, as a pre- dominantly central structure, is largely spared in these cases. It is thus widely thought that a device-based prosthetic approach to restoration of visual function will be effective and will enjoy similar success as cochlear implants have for restoration of auditory function. In this article the authors review the potential locations for stimulation electrode placement for visual prostheses, assessing the anatomical and functional advantages and disadvantages of each. Of particular interest to the neurosurgical community is placement of deep brain stimulating electrodes in thalamic structures that has shown substantial promise in an animal model. The theory of operation of visual prostheses is discussed, along with a review of the current state of knowledge. Finally, the visual prosthesis is proposed as a model for a general high-fidelity machine-brain interface.(DOI: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0986) KEY WOR ds • visual prosthesis • deep brain stimulation • visual function N this article we review the current state of visual Evaluating Points Along the Early prosthetics with particular attention to the approaches Visual Pathway as Stimulation Targets that include neurosurgical methodologies. I There are 6 locations along the visual pathway with potential for functional restoration of sight through mi- Background: Causes of Blindness crostimulation as depicted in Fig. -

Novel Multimodality Imaging in the Planning and Surgical Treatment of Epilepsy

Novel Multimodality Imaging in the Planning and Surgical Treatment of Epilepsy Mr Mark John Nowell Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Clinical and Experimental Epilepsy Institute of Neurology University College London August 2015 Declaration I, Mark Nowell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: Date: 1 Abstract Over 50 million people worldwide are affected by epilepsy and in one third of these the condition is poorly controlled by medication. In these patients epilepsy surgery offers potentially curative treatment. The presurgical evaluation and surgical management of epilepsy is complex. Patients typically undergo a range of imaging modalities, and may also require intracranial EEG (ic- EEG) evaluation. Cortical resections are informed by these investigations, with the aim of removing the epileptogenic zone (EZ) without causing any functional deficits. I have investigated the use of 3D multimodality image integration (3DMMI) and it’s relevance in epilepsy surgery in adults. I have supported the use of 3DMMI in our busy epilepsy surgery unit, and demonstrated that disclosure of models changes and informs clinical decision making during presurgical evaluation and surgical planning. EpiNavTM is custom-designed software for use in epilepsy surgery, representing an image- guided solution to address the complexities of the pipeline. I have incorporated this software into our clinical workflow and demonstrated the potential benefits of computer-assistance in planning depth electrode implantations. 3DMMI and EpiNav have been crucial in the development of the stereoEEG (SEEG) service in our unit. -

Visualpath Dental 2010.Jnt

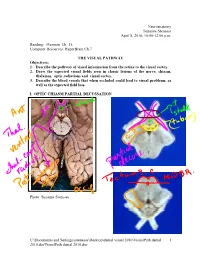

Neuroanatomy Suzanne Stensaas April 8, 2010, 10:00-12:00 p.m. Reading: Waxman Ch. 15, Computer Resources: HyperBrain Ch 7 THE VISUAL PATHWAY Objectives: 1. Describe the pathway of visual information from the retina to the visual cortex. 2. Draw the expected visual fields seen in classic lesions of the nerve, chiasm, thalamus, optic radiations and visual cortex. 3. Describe the blood vessels that when occluded could lead to visual problems, as well as the expected field loss. I. OPTIC CHIASM PARTIAL DECUSSATION Photo: Suzanne Stensaas C:\Documents and Settings\sstensaas\Desktop\dental visual 2010\VisualPath dental 1 2010.docVisualPath dental 2010.doc II. OPTIC TRACT Ganglion cell axons diverge A. 90% go to Lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of thalamus (the retino- geniculo-calcarine path ) B. 10% go to Superior colliculus and pretectum (the retinocollicular path for reflexes) C. The hypothalamus for circadian rhythms (not to be discussed) III. THALAMIC RELAY NUCLEUS -- the LATERAL GENICULATE NUCLEUS OR BODY A. Specific retinotopic projection. B. Six layers. Three layers get input from from each eye. Thalamus Red LGN LGN Nucleus C:\Documents and Settings\sstensaas\Desktop\dental visual 2010\VisualPath dental 2 2010.docVisualPath dental 2010.doc The optic tract projects to the LGN Crainial Nerves, Wilson-Pauwels et al., 1988 IV. OPTIC RADIATIONS A. Retinotopic organization from the LGN neurons to the cortex. B. Axons of neurons in the lateral geniculate form the optic radiations = geniculocalcarine tract. The retinotopic organization is maintained. 1. Some loop forward over inferior (or temporal) horn of lateral ventricle = Meyer's Loop 2. Other axons take a more direct posterior course through the deep parietal white matter.