Winds of Change: Perspectives on the World's Search for Stable Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H-Diplo Article Roundtable Review, Vol. X, No. 24

2009 h-diplo H-Diplo Article Roundtable Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web Editor: George Fujii Review Introduction by Thomas Maddux www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Reviewers: Bruce Craig, Ronald Radosh, Katherine A.S. Volume X, No. 24 (2009) Sibley, G. Edward White 17 July 2009 Response by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr Journal of Cold War Studies 11.3 (Summer 2009) Special Issue: Soviet Espoinage in the United States during the Stalin Era (with articles by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr; Eduard Mark; Gregg Herken; Steven T. Usdin; Max Holland; and John F. Fox, Jr.) http://www.mitpressjournals.org/toc/jcws/11/3 Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-X-24.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University, Northridge.............................. 2 Review by Bruce Craig, University of Prince Edward Island ..................................................... 8 Review by Ronald Radosh, Emeritus, City University of New York ........................................ 16 Review by Katherine A.S. Sibley, St. Josephs University ......................................................... 18 Review by G. Edward White, University of Virginia School of Law ........................................ 23 Author’s Response by John Earl Haynes, Library of Congress, and Harvey Klehr, Emory University ................................................................................................................................ 27 Copyright © 2009 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. -

Introduction: Perspectives on the World's Search for Stable Democracy

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 1 (1992) Issue 2 "Winds of Change" Symposium Article 2 October 1992 Introduction: Perspectives on the World's Search for Stable Democracy Rodney A. Smolla Darlene P. Bradberry Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Comparative Politics Commons Repository Citation Rodney A. Smolla and Darlene P. Bradberry, Introduction: Perspectives on the World's Search for Stable Democracy, 1 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 177 (1992), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmborj/vol1/iss2/2 Copyright c 1992 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj WILLIAM AND MARY BILL OF RIGHTS JOURNAL VOLUME 1 FALL 1992 ISSUE 2 WINDS OF CHANGE: PERSPECTIVES ON THE WORLD'S SEARCH FOR STABLE DEMOCRACY by Rodney A. Smolla* and Darlene P. Bradberry** I. In November 1992, the German government summoned the citizens of Germany to stage a march through Berlin in a massive demonstration of the nation's commitment to tolerance and human rights. The march was scheduled to coincide with the anniversary of two events in German history, one monstrous and one triumphant: the commencement in 1938 of the Nazi Kristallnacht pogrom against Jews, and the 1989 fall of the )erlin Wall. The march should have been a celebration of peace and hope, a signal to the world that the reunited Germany was dedicated to equality, the rule of law, and protection of human dignity. Indeed the German government and the vast majority of the German people are so dedicated. -

Political Views of Paul Robeson - Wikipedia

8/27/2021 Political views of Paul Robeson - Wikipedia [ Political views of Paul Robeson. (Accessed Aug. 27, 2021). Overview Wikipedia. ] Political views of Paul Robeson Entertainer and activist Paul Robeson's political philosophies and outspoken views about domestic and international Communist countries and movements were the subject of great concern to the western mass media and the United States Government, during the Cold War. His views also caused controversy within the ranks of black organizations and the entertainment industry. Robeson was never officially identified as a member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), domestically or internationally. Robeson's beliefs in socialism, his ties to the CPUSA and leftist trade unions, and his experiences in the USSR continue to cause controversy among historians and scholars as well as fans and journalists. Contents First visit to the Soviet Union (1934) Soviet constitution and anti-racist climate Robeson's early views on the USSR and communism is greate for the peoples Reactions to Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact Tenney Committee statement Mundt-Nixon Bill and Smith Act Itzik Feffer meeting and concert in Tchaikovsky Hall (June 1949) Accounts of the meeting Robeson's speaks publicly of Feffer Silence on Stalin Jackie Robinson's testimony to HUAC (April 1949) Views on Stalin Stalin Peace Prize and Stalin eulogy (1952–1953) Robeson and House Un-American Activities Committee (1956) Possible challenge to Soviet policies Later views of communism (1960s) References First visit to the Soviet Union (1934) Robeson journeyed to the Soviet Union in December 1934, via Germany, having been given an official invitation. While there, Robeson was welcomed by playwrights, artists and filmmakers, among them Sergei Eisenstein who became a close friend.[1] Robeson also met with African Americans who had migrated to the USSR including his two brothers-in-law.[2] Robeson was accompanied by his wife, Eslanda Goode Robeson and his biographer and friend, Marie Seton. -

Between Integration and Resettlement: the Meskhetian Turks

BETWEEN INTEGRATION AND RESETTLEMENT: THE MESKHETIAN TURKS Oskari Pentikäinen and Tom Trier ECMI Working Paper # 21 September 2004 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES (ECMI) Schiffbruecke 12 (Kompagnietor Building) D-24939 Flensburg Germany ( +49-(0)461-14 14 9-0 fax +49-(0)461-14 14 9-19 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ecmi.de ECMI Working Paper # 21 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Director: Marc Weller © Copyright 2004 by the European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Published in August 2004 by the European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) List of Abbreviations.................................................................................................4 I. Introduction...........................................................................................................6 1. Who Are the Meskhetian Turks?...........................................................................9 2. A History of Forced Migration............................................................................11 II. The Meskhetian Turks’ Current Demographic and Socio-Political Situation.......13 1. Georgia...............................................................................................................15 2. Azerbaijan...........................................................................................................19 3. Ukraine...............................................................................................................20 4. Russia..................................................................................................................21 -

The Prophecy That Is Shaping History

The Prophecy That Is Shaping History: New Research on Ezekiel’s Vision of the End Jon Mark Ruthven, PhD Ihab Griess, PhD Xulon Press 11350 Random Hills Drive #800 Fairfax, Virginia 22030 Copyright Jon Mark Ruthven © 2003 In memoriam Pamela Jessie Ruthven PhD, LCSW 26 March 1952 – 9 April 2001 Wife, mother, and faithful friend i Preface Great events in history often gather momentum and power long before they are recognized by the experts and commentators on world affairs. Easily one of the most neglected but powerfully galvanizing forces shaping history in the world today is the prophecy of Gog and Magog from the 38th and 39th chapters of the book of Ezekiel. This prophecy from the Jewish-Christian Bible has molded geo-politics, not only with- in the United States and the West but also, to an amazing degree, in the Muslim world as well. It seems that, millennia ago, Ezekiel’s vision actually named the nation which millions today believe plays the major role in this prophecy: the nation of Russia. Many modern scholars have dismissed Ezekiel’s Gog and Magog prophecy as a mystical apocalypse written to vindicate the ancient claims of a minor country’s deity. The very notion of such a prediction—that semi-mythical and unrelated nations that dwelt on the fringes of Israel’s geographical consciousness 2,500 years ago would, “in the latter days,” suddenly coalesce into a tidal wave of opposition to a newly regathered state of Jews—seems utterly incredible to a modern mentality. Such a scenario, the experts say, belongs only to the fundamentalist “pop religion” of The Late, Great Planet Earth and of TV evangelists. -

Conflicts in the North Caucasus

Central Asian Survey, (1998), 17(3), 409-441. Conflicts in the North Caucasus SVANTE E. CORNELL* Although the conflicts that have attracted most international attention in the post- cold war era have been those of the Transcaucasus, another area of both potential and actual turmoil is the North Caucasus. The first example of serious conflicts in the area, naturally, is the war in Chechnia. However, the existence of this war, and its astonishing cruelty and devastation, has been instrumental in obscuring the other grievances that exist in the area, and that have the potential to escalate into open conflict. These can be divided into two main categories, which however spill over into one another. The first type of conflicts are those among the peoples of the region; the second type is conflicts between these peoples and Russia. Doubtlessly, the main example of the unrest in the North Caucasus has been the short but bloody war between the Ingush and the Ossetians. However, this war distinguishes itself only by being the only one of the conflicts in the region that has escalated into war. Among the other known problems, three issues call for special attention: First and perhaps most pressingly, the bid for unity of the Lezgian people in Dagestan and Azerbaijan; Second, the latent problem between the Turkic Karachai and the Circasssian peoples in the two neighbour republics of Karachaevo-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria; and thirdly the condition of the most complex of all the North Caucasian republics: Dagestan. It seems logical in this study to start with the most well-known of these issues: the war that raged in November 1992 in the Prigorodniy raion between the Ingush and the North Ossetians. -

Washington Decoded

Washington Decoded 11 June 2009 In Denial: Round 11 By John Earl Haynes & Harvey Klehr While we were writing Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America, based on Alexander Vassiliev’s notebooks, we anticipated a hostile reaction from battered but still rancorous remnants of the pro-Communist left in the academic world and partisan pundits. Together they have denied for more than fifty years that Soviet espionage in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s had much significance, denounced claims linking the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) with Soviet espionage, and proclaimed the innocence of many of those identified as Soviet agents. We expected the most antagonistic reaction would involve the traditionally two most contested cases: that of Alger Hiss, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. No one who studies 20th century American history can fail to be astounded by the quantity and the viciousness of the assaults leveled on scholars who dared question the innocence and martyrdom of Hiss and the Rosenbergs. Historians Allen Weinstein and Ronald Radosh, most notably, were subjected to years of attacks on their personal integrity and professional competence for their pioneering and superbly researched books on the Hiss- Chambers and Rosenberg cases.[1] The opening chapter of Spies, entitled “Alger Hiss: Case Closed,” ended with our conclusion that in light of new and definitive evidence from the KGB archives recorded in Vassiliev’s notebooks, as well as the ample evidence available earlier from other sources, “to serious students of history continued claims for Hiss’s innocence are akin to a terminal form of ideological blindness.” But we also noted, “it is unlikely that anything will convince the remaining die-hards.”[2] Similarly, we foresaw continued protests of innocence from the ranks (albeit much-thinned ranks) of the Rosenberg defenders in the academy and elsewhere to the extensive documentation in Spies of the extraordinary size of the espionage apparatus Rosenberg established. -

Reactions of Congress to the Alger Hiss Case, 1948-1960

Soviet Spies and the Fear of Communism in America Reactions of Congress to the Alger Hiss Case, 1948-1960 Mémoire Brigitte Rainville Maîtrise en histoire Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Brigitte Rainville, 2013 Résumé Le but de ce mémoire est de mettre en évidence la réaction des membres du Congrès des États-Unis dans le cadre de l'affaire Alger Hiss de 1948 à 1960. Selon notre source principale, le Congressional Record, nous avons pu faire ressortir les divergences d'opinions qui existaient entre les partisans des partis démocrate et républicain. En ce qui concerne les démocrates du Nord, nous avons établi leur tendance à nier le fait de l'infiltration soviétique dans le département d'État américain. De leur côté, les républicains ont profité du cas de Hiss pour démontrer l'incompétence du président Truman dans la gestion des affaires d'État. Il est intéressant de noter que, à la suite de l'avènement du républicain Dwight D. Eisenhower à la présidence en 1953, un changement marqué d'opinions quant à l'affaire Hiss s'opère ainsi que l'attitude des deux partis envers le communisme. Les démocrates, en fait, se mettent à accuser l'administration en place d'inaptitude dans l'éradication des espions et des communistes. En ayant recours à une stratégie similaire à celle utilisée par les républicains à l'époque Truman, ceux-ci n'entachent toutefois guère la réputation d'Eisenhower. Nous terminons en montrant que le nom d'Alger Hiss, vers la fin de la présidence Eisenhower, s'avère le symbole de la corruption soviétique et de l'espionnage durant cette période marquante de la Guerre Froide. -

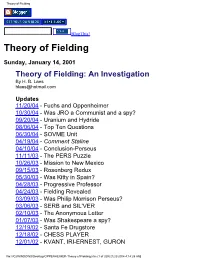

Theory of Fielding

Theory of Fielding BlogThis! Theory of Fielding Sunday, January 14, 2001 Theory of Fielding: An Investigation By H. B. Laes [email protected] Updates 11/20/04 - Fuchs and Oppenheimer 10/30/04 - Was JRO a Communist and a spy? 09/20/04 - Uranium and Hydride 08/06/04 - Top Ten Questions 06/30/04 - SOVME Unit 04/19/04 - Comment Staline 04/10/04 - Conclusion-Perseus 11/11/03 - The PERS Puzzle 10/26/03 - Mission to New Mexico 09/15/03 - Rosenberg Redux 05/30/03 - Was Kitty in Spain? 04/28/03 - Progressive Professor 04/24/03 - Fielding Revealed 03/09/03 - Was Philip Morrison Perseus? 03/06/03 - SERB and SIL'VER 02/10/03 - The Anonymous Letter 01/07/03 - Was Shakespeare a spy? 12/19/02 - Santa Fe Drugstore 12/18/02 - CHESS PLAYER 12/01/02 - KVANT, IRI-ERNEST, GURON file:///C|/WINDOWS/Desktop/OPPENHEIMER-Theory of Fielding.htm (1 of 329) [12/2/2004 4:14:25 AM] Theory of Fielding 11/10/02 - Goldsmith 09/17/02 - The Mironov-Zarubin Affair 09/01/02 - Sacred Secrets 12/19/01 - MAR and "D" 12/01/01 - Feklisov 08/26/01 - Gold Testimony 07/05/01 - Japan 05/25/01 - Mitrokhin Contents Introduction Set A - Comment Staline Set B - Spanish Civil War Set C - FOGEL'-PERS Set D - Drugstore Safehouse Set E - The Eltenton-Chevalier Incident Set F - Prodigy, Prankster, Scientist, Spy Set G - VEKSEL, KVANT, IRI-ERNEST, GURON Set H - Hero of Russia Set I - RELE-SERB Set J - September, 1941 Set K - MLAD's Report Set L - Mission to New Mexico Set M - MAR and "D" Set N - Post Los Alamos, 1945 Set O - A Freeze in 1946 Set P - Shelter Island and Paris, 1947 Set Q - 1948, -

“Frozen Conflicts” in Europe Anton Bebler (Ed.)

“Frozen conflicts” in Europe Anton Bebler (ed.) “Frozen conflicts” in Europe Barbara Budrich Publishers Opladen • Berlin • Toronto 2015 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8474-0428-6. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org © 2015 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0. (CC- BY-SA 4.0) It permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you share under the same license, give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ © 2015 Dieses Werk ist beim Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH erschienen und steht unter der Creative Commons Lizenz Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Diese Lizenz erlaubt die Verbreitung, Speicherung, Vervielfältigung und Bearbeitung bei Verwendung der gleichen CC-BY-SA 4.0-Lizenz und unter Angabe der UrheberInnen, Rechte, Änderungen und verwendeten Lizenz. This book is available as a free download from www.barbara-budrich.net (https://doi.org/10.3224/84740133). A paperback version is available at a charge. The page numbers of the open access edition correspond with the paperback edition. -

Kennan Institute

KENNAN INSTITUTE Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Tel (202) 691-4100 Fax (202) 691-4247 www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan ISSN: 1931-2083 KENNAN INSTITUTE Annual Report 2009–2010 KENNAN INSTITUTE Annual Report 2009–2010 1 KENNAN INSTITUTE KENNAN INSTITUTE Also employed at the Kennan RESEARCH ASSISTANTS Woodrow Wilson International Center Institute during the 2009–10 2009–10 for Scholars program year: Zoya Appel, Wanda Archy, One Woodrow Wilson Plaza Summer Brown, Program Specialist Kathryn Beckett, Oleksandr Chorny, 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Larissa Eltsefon, Editorial Assistant Amy Freeman, Eugene Imas, Washington, DC 20004-3027 Lidiya Zubytska, Program Assistant Aika Karimova, George Kobakhikdze, Tel (202) 691-4100 Monique Principi, Program Specialist Patrick Lang, Emily Linehan, Fax (202) 691-4247 Alice Krupit, Program Assistant Bryce Lively, Alla Malova, Wallis Nader, www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan Brandon Payne, Peter Piatetsky, Alex Rekhtman, Ekaterina Reyzis, Yevgen KENNAN MOSCOW PROJECT Sautin, Lauren Schmuck, Richard KENNAN INSTITUTE STAFF Galina Levina, Program Manager Schrader, Nazar Sharunenko, Dennis Blair A. Ruble, Director Ekaterina Alekseeva, Program Manager Shiraev, Diana Sweet, William E. Pomeranz, Deputy Director and Editor Vickie Tsombanos, Lidia Tutarinova, F. Joseph Dresen, Program Associate Irina Petrova, Office Manager Lolita Voinich, Jacob Zenn Mary Elizabeth Malinkin, Program Pavel Korolev, Program Officer Associate Anna Toker, Accountant ISSN: 1931-2083 Edmita Bulota, Program Assistant Lauren Crabtree, Program Assistant Amy Liedy, Editorial Assistant KENNAN KYIV PROJECT Yaroslav Pylynskyi, Project Manager Nataliya Samozvanova, Office Manager 2 CONTENTS OVERVIEW 3 DIRECTOR’S REVIEW 7 ADVISORY COUNCILS 10 KENNAN COUNCIL 11 SCHOLARS 13 ZNAMENSKOE-RAEK, ESTATE HOUSE, RAEK, TVER’, RUSSIA (WILLIAM C. -

Moses Finley and Politics Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition

Moses Finley and Politics Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition Editorial Board William V. Harris (editor) Alan Cameron, Suzanne Said, Kathy H. Eden, Gareth D. Williams, Holger A. Klein VOLUME 40 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/csct Moses Finley and Politics Edited by W. V. Harris LEIDEn • bOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Moses Finley c. 1947. Photo from the collection of his younger sister, Dr Gertrude Finkelstein, by kind permission of his nieces Sharon Finley and Lia Barrad and his nephew Joel Tepp. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moses Finley and politics / edited by W.V. Harris. pages cm. — (Columbia studies in the classical tradition ; volume 40) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26167-9 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-26169-3 (e-book) 1. Finley, M. I. (Moses I.), 1912–1986—Political and social views. 2. Classicists—United States— Biography. 3. Classicists—Great Britain—Biography. 4. Economic history—To 500. 5. Anti-communist movements—United States. I. Harris, William V. (William Vernon) author, editor of compilation. PA85.F48M67 2013 938.007202—dc23 [B] 2013032206 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 0166-1302 ISBN 978-90-04-26167-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-26169-3 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York.