Separate Opinion of Judge Ad Hoc Sreenivasa Rao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Island of Palmas Case: Mere Proximity Was Not an Adequate Claim to Land Island of Palmas Case, (Scott, Hague Court Reports 2D 83 (1932), (Perm

island of Palmas case: mere proximity was not an adequate claim to land Island of Palmas Case, (Scott, Hague Court Reports 2d 83 (1932), (Perm. Ct. Arb. 1928), 2 U.N. Rep. Intl. Arb. Awards 829), was a case involving a territorial dispute over the Island of Palmas (or Miangas) between the Netherlands and the United States which was heard by the Permanent Court of Arbitration. The Island of Palmas (known as Pulau Miangas in Bahasa Indonesian) is now within Indonesian sovereignty. This case is one of the most highly influential precedents dealing with island territorial conflicts. Facts of the case Palmas, also referred to as Miangas, is an island of little economic value or strategic location. It is two miles in length, three-quarters of a mile in width, and had a population of about 750 when the decision of the arbitrator was handed down. The island is located between Mindanao, Philippines and the northern most island, known as Nanusa, of what was the former Netherlands East Indies. In 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1898) and Palmas sat within the boundaries of that cession to the U.S. In 1906, the United States discovered that the Netherlands also claimed sovereignty over the island, and the two parties agreed to submit to binding arbitration by the Permanent Court of Arbitration. On January 23, 1925, the two government signed an agreement to that effect. Ratifications were exchanged in Washington on April 1, 1925. The agreement was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on May 19, 1925.[1] The arbitrator in the case was Max Huber, a Swiss national. -

Building ASEAN Community: Political–Security and Socio-Cultural Reflections

ASEAN@50 Volume 4 Building ASEAN Community: Political–Security and Socio-cultural Reflections Edited by Aileen Baviera and Larry Maramis Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia © Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic or mechanical without prior written notice to and permission from ERIA. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, its Governing Board, Academic Advisory Council, or the institutions and governments they represent. The findings, interpretations, conclusions, and views expressed in their respective chapters are entirely those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, its Governing Board, Academic Advisory Council, or the institutions and governments they represent. Any error in content or citation in the respective chapters is the sole responsibility of the author/s. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Cover Art by Artmosphere Design. Book Design by Alvin Tubio. National Library of Indonesia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN: 978-602-8660-98-3 Department of Foreign Affairs Kagawaran ng Ugnayang Panlabas Foreword I congratulate the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), the Permanent Mission of the Philippines to ASEAN and the Philippine ASEAN National Secretariat for publishing this 5-volume publication on perspectives on the making, substance, significance and future of ASEAN. -

The Case of Dokdo

Resolution of Territorial Disputes in East Asia: The Case of Dokdo Laurent Mayali & John Yoo* This Article seeks to contribute to solving of the Korea-Japan territorial dispute over Dokdo island (Korea)/Takeshima (Japanese). The Republic of Korea argues that Dokdo has formed a part of Korea since as early as 512 C.E.; as Korea currently exercises control over the island, its claim to discovery would appear to fulfill the legal test for possession of territory. Conversely, the Japanese government claims that Korea never exercised sufficient sovereignty over Dokdo. Japan claims that the island remained terra nullius—in other words, territory not possessed by any nation and so could be claimed—until it annexed Dokdo in 1905. Japan also claims that in the 1951 peace treaty ending World War II, the Allies did not include Dokdo in the list of islands taken from Japan, which implies that Japan retained the island in the postwar settlement. This article makes three contributions. First, it brings forward evidence from the maps held at various archives in the United States and Western Europe to determine the historical opinions of experts and governments about the possession of Dokdo. Second, it clarifies the factors that have guided international tribunals in their resolution of earlier disputes involving islands and maritime territory. Third, it shows how the claim of terra nullius has little legitimate authority when applied to East Asia, an area where empires, kingdoms, and nation-states had long exercised control over territory. * Laurent Mayali is the Lloyd M. Robbins Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley School of Law; John Yoo is the Emanuel S. -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

Case Concerning Sovereignty Over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore)

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE REPORTS OF JUDGMENTS, ADVISORY OPINIONS AND ORDERS CASE CONCERNING SOVEREIGNTY OVER PEDRA BRANCA/PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS AND SOUTH LEDGE (MALAYSIA/SINGAPORE) JUDGMENT OF 23 MAY 2008 2008 COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE RECUEIL DES ARRE|TS, AVIS CONSULTATIFS ET ORDONNANCES AFFAIRE RELATIVE Av LA SOUVERAINETÉ SUR PEDRA BRANCA/PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS ET SOUTH LEDGE (MALAISIE/SINGAPOUR) ARRE|T DU 23 MAI 2008 Official citation: Sovereignty over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2008,p.12 Mode officiel de citation: Souveraineté sur Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks et South Ledge (Malaisie/Singapour), arrêt, C.I.J. Recueil 2008,p.12 Sales number ISSN 0074-4441 No de vente: 937 ISBN 978-92-1-071046-6 23 MAY 2008 JUDGMENT SOVEREIGNTY OVER PEDRA BRANCA/ PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS AND SOUTH LEDGE (MALAYSIA/SINGAPORE) SOUVERAINETÉ SUR PEDRA BRANCA/ PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS ET SOUTH LEDGE (MALAISIE/SINGAPOUR) 23 MAI 2008 ARRE|T 12 TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs 1. CHRONOLOGY OF THE PROCEDURE 1-15 2. GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION AND CHARACTERISTICS 16-19 3. GENERAL HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 20-29 4. HISTORY OF THE DISPUTE 30-36 5. SOVEREIGNTY OVER PEDRA BRANCA/PULAU BATU PUTEH 37-277 5.1. Arguments of the Parties 37-42 5.2. The question of the burden of proof 43-45 5.3. Legal status of Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh before the 1840s 46-117 5.3.1. Original title to Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh 46-80 5.3.2. -

Non-Corrigé Uncorrected

Non-Corrigé Uncorrected CR 2007/23 International Court Cour internationale of Justice de Justice THE HAGUE LA HAYE YEAR 2007 Public sitting held on Friday 9 November 2007, at 10 a.m., at the Peace Palace, Vice-President Al-Khasawneh, Acting President, presiding in the case concerning Sovereignty over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore) ________________ VERBATIM RECORD ________________ ANNÉE 2007 Audience publique tenue le vendredi 9 novembre 2007, à 10 heures, au Palais de la Paix, sous la présidence de M. Al-Khasawneh, vice-président, faisant fonction de président en l’affaire relative à la Souveraineté sur Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks et South Ledge (Malaisie/Singapour) ____________________ COMPTE RENDU ____________________ - 2 - Present: Vice-President Al-Khasawneh, Acting President Judges Ranjeva Shi Koroma Parra-Aranguren Buergenthal Simma Tomka Abraham Keith Sepúlveda-Amor Bennouna Skotnikov Judges ad hoc Dugard Sreenivasa Rao Registrar Couvreur ⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯ - 3 - Présents : M. Al-Khasawneh, vice-président, faisant fonction de président en l’affaire MM. Ranjeva Shi Koroma Parra-Aranguren Buergenthal Simma Tomka Abraham Keith Sepúlveda-Amor Bennouna Skotnikov, juges MM. Dugard Sreenivasa Rao, juges ad hoc M. Couvreur, greffier ⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯ - 4 - The Government of Malaysia is represented by: H.E. Tan Sri Abdul Kadir Mohamad, Ambassador-at-Large, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Malaysia, Adviser for Foreign Affairs to the Prime Minister, as Agent; H.E. Dato’ Noor Farida Ariffin, Ambassador of Malaysia to the Kingdom of the Netherlands, as Co-Agent; H.E. Dato’ Seri Syed Hamid Albar, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Malaysia, Tan Sri Abdul Gani Patail, Attorney-General of Malaysia, Sir Elihu Lauterpacht, C.B.E., Q.C., Honorary Professor of International Law, University of Cambridge, member of the Institut de droit international, member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, Mr. -

The World Factbook

The World Factbook East & Southeast Asia :: Malaysia Introduction :: Malaysia Background: During the late 18th and 19th centuries, Great Britain established colonies and protectorates in the area of current Malaysia; these were occupied by Japan from 1942 to 1945. In 1948, the British-ruled territories on the Malay Peninsula except Singapore formed the Federation of Malaya, which became independent in 1957. Malaysia was formed in 1963 when the former British colonies of Singapore, as well as Sabah and Sarawak on the northern coast of Borneo, joined the Federation. The first several years of the country's independence were marred by a communist insurgency, Indonesian confrontation with Malaysia, Philippine claims to Sabah, and Singapore's withdrawal in 1965. During the 22-year term of Prime Minister MAHATHIR bin Mohamad (1981-2003), Malaysia was successful in diversifying its economy from dependence on exports of raw materials to the development of manufacturing, services, and tourism. Prime Minister Mohamed NAJIB bin Abdul Razak (in office since April 2009) has continued these pro-business policies and has introduced some civil reforms. Geography :: Malaysia Location: Southeastern Asia, peninsula bordering Thailand and northern one-third of the island of Borneo, bordering Indonesia, Brunei, and the South China Sea, south of Vietnam Geographic coordinates: 2 30 N, 112 30 E Map references: Southeast Asia Area: total: 329,847 sq km country comparison to the world: 67 land: 328,657 sq km water: 1,190 sq km Area - comparative: slightly larger -

Case Concerning Sovereignty Over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore)

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE REPORTS OF JUDGMENTS, ADVISORY OPINIONS AND ORDERS CASE CONCERNING SOVEREIGNTY OVER PEDRA BRANCA/PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS AND SOUTH LEDGE (MALAYSIA/SINGAPORE) JUDGMENT OF 23 MAY 2008 2008 COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE RECUEIL DES ARRE|TS, AVIS CONSULTATIFS ET ORDONNANCES AFFAIRE RELATIVE Av LA SOUVERAINETÉ SUR PEDRA BRANCA/PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS ET SOUTH LEDGE (MALAISIE/SINGAPOUR) ARRE|T DU 23 MAI 2008 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/feab3a/ Official citation: Sovereignty over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2008,p.12 Mode officiel de citation: Souveraineté sur Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks et South Ledge (Malaisie/Singapour), arrêt, C.I.J. Recueil 2008,p.12 Sales number ISSN 0074-4441 No de vente: 937 ISBN 978-92-1-071046-6 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/feab3a/ 23 MAY 2008 JUDGMENT SOVEREIGNTY OVER PEDRA BRANCA/ PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS AND SOUTH LEDGE (MALAYSIA/SINGAPORE) SOUVERAINETÉ SUR PEDRA BRANCA/ PULAU BATU PUTEH, MIDDLE ROCKS ET SOUTH LEDGE (MALAISIE/SINGAPOUR) 23 MAI 2008 ARRE|T PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/feab3a/ 12 TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs 1. CHRONOLOGY OF THE PROCEDURE 1-15 2. GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION AND CHARACTERISTICS 16-19 3. GENERAL HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 20-29 4. HISTORY OF THE DISPUTE 30-36 5. SOVEREIGNTY OVER PEDRA BRANCA/PULAU BATU PUTEH 37-277 5.1. Arguments of the Parties 37-42 5.2. The question of the burden of proof 43-45 5.3. Legal status of Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh before the 1840s 46-117 5.3.1. -

Malaysia and Brunei: an Analysis of Their Claims in the South China Sea J

A CNA Occasional Paper Malaysia and Brunei: An Analysis of their Claims in the South China Sea J. Ashley Roach With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Cleared for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA Foreword This is the second of three legal analyses commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. Policy Options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain J. -

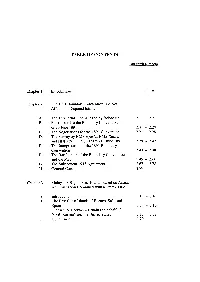

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraoh numbers Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 - 1.10 Chapter 2 The 1891 Boundary Convention Did Not Affect the Disputed Islands The Territorial Title Alleged by Indonesia Background to the Boundary Convention of 20 June 189 1 The Negotiations for the 189 1 Convention The Survey by HMS Egeria, HMS Rattler and HNLMS Banda, 30 May - 19 June 1891 The Interpretation of the 189 1 Boundary Convention The Ratification of the Boundary Convention and the Map The Subsequent 19 15 Agreement General Conclusions Chapter 3 Malaysia's Right to the Islands Based on Actual Administration Combined with a Treaty Title A. Introduction 3.1 - 3.4 B. The East Coast Islands of Borneo, Sulu and Spain 3.5 - 3.16 C. Transactions between Britain (on behalf of North Borneo) and the United States 3.17 - 3.28 D. Conclusion 3.29 Chapter 4 The Practice of the Parties and their Predecessors Confirms Malaysia's Title A. Introduction B. Practice Relating to the Islands before 1963 C. Post-colonial Practice D. General Conclusions Chapter 5 Officia1 and other Maps Support Malaysia's Title to the Islands A. Introduction 5.1 - 5.3 B. Indonesia's Arguments Based on Various Maps 5.4 - 5.30 C. The Relevance of Maps in Determining Disputed Boundaries 5.31 - 5.36 D. Conclusions from the Map Evidence as a Whole 5.37 - 5.39 Submissions List of Annexes Appendix 1 The Regional History of Northeast Bomeo in the Nineteenth Century (with special reference to Bulungan) by Prof. Dr. Vincent J. H. Houben Table of Inserts Insert Descri~tion page 1. -

Apr–Jun 2019

Vol. 15 Issue 01 APR–JUN 2019 04 / Reflections on War 06 / Evidence from the Archives 22 / When Food Was Scarce 34 / Retro Disco Scene 52 / Three Records from History The Archives Issue The National Archives Turns 50 p. 10 biblioasia VOLUME 15 APR April 2019 is a special month for the National Archives of Singapore (NAS). After an 18-month JUN makeover, the NAS building at Canning Rise re-opened on 7 April with a slew of upgraded ISSUE 01 2019 Directors’ CONTENTS facilities for the public. As the NAS’ year-long 50th anniversary celebrations that began in June 2018 draw to a conclusion, we will mark its close by hosting the SARBICA* International OPINION Note Symposium from 24–28 June 2019. This special edition of BiblioAsia puts the spotlight on all things archives. In his op-ed, Dr Shashi Jayakumar describes how recent initiatives undertaken by the NAS prepare the organisation – as well as Singapore – for the future. Eric Chin examines the role of the archives in providing evidence and the value this has for Singapore – from resolving the landmark Pedra Branca dispute to helping bring the past to life for today’s generation. Fiona Tan remembers some of the pioneers who started the archives in Singapore, Mark Looking Back, The Unresolved Past: Wong interviews an archives veteran to glean insights into her 45-year career, and Abigail 02 Looking Forward 04 Reflections on War Huang charts the timeline of the archives buildings over the years (we did say this issue is and Memory about the archives!). Cheong Suk-Wai stresses the importance of oral history records and tells us why the life of a humble tailor matters as much as that of the tycoon. -

Island of Palmas Case (Netherlands, USA)

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Island of Palmas case (Netherlands, USA) 4 April 1928 VOLUME II pp. 829-871 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2006 XX. ISLAND OF PALMAS CASE1. PARTIES: Netherlands, U.S.A. SPECIAL AGREEMENT: January 23, 1925. ARBITRATOR: Max Huber (Switzerland). AWARD: The Hague, April, 1928. Territorial sovereignty.—Contiguity and title to territory.—Continuous and peaceful display of sovereignty.—The "intertemporal" law.—Rules of evidence in international proceedings.—Maps as evidence.—Inchoate title.—Passivity in relation to occupation.—Dutch East India Company as subject of international law.—Treaties with native princes.—Subsequent practice as an element of interpretation. 1 For bibliography, index and tables, see Volume III. 831 Special Agreement. [See beginning of Award below.] AWARD OF THE TRIBUNAL. Award of the tribunal of arbitration tendered in conformity with the special agreement concluded an January 23, 1925, between the United States of America and the Netherlands relating to the arbitratiov. of differences respecting sovereignty over the Island ofPalmas [or Miangas).—The Hague. April 4, 1928. An agreement relating to the arbitration of differences respecting sover- eignty over the Island of Palmas (or Miangas) was signed by the United States oi" America and the Netherlands on January 23rd, 1925. The text of the agreement runs as follows : The United States of America and Her Majesty the Queen of the Netherlands, Desiring to terminate in accordance with