THE ANNALS of IOWA 70 (Winter 2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eminent Philosopher a Passion for Languages Physicist and Philosopher

tics from the University of Wisconsin, teaches his class, Linguistic Problems Eminent Philosopher Madison, in 1955. in the Teaching of English as a Foreign With his passion for languages, Saitz Language. “I cannot fi ll his shoes, of !""##$ %&'(&##", 86, a College of was an expert in applied linguistics and course, but for one night a week I can Arts & Sciences professor emeritus of kinesics, or gestures, who “found humor try.” ()&&*+)# ,"-)$ (.%!’16) philosophy, on August 12, 2015. in the way people would say things and One of the world’s eminent philosoph- even in the crazy rules of English,” says Physicist and Philosopher ers and logicians, Hintikka was born in his son, Richard Saitz (CAS’87, MED’87), Vantaa, Finland, in 1929, a BU School of Public Health "*'+) -%&0$'1, 87, a College of and educated at the Uni- professor and chair of com- Arts & Sciences professor emeritus versity of Helsinki, where munity health sciences and a of philosophy and of physics, on Aug- he earned a PhD in phi- School of Medicine profes- ust 8, 2015. losophy in 1956. sor of medicine. “He married Shimony’s research transcended dis- In 1990, he joined the BU my mom, who was primarily ciplinary boundaries and literary genres. philosophy faculty, where Hintikka a Spanish speaker, and he He made lasting contributions to the ar- his expertise in game- seemed to really enjoy people eas of inductive logic, the philosophy of theoretical semantics and epistemic who spoke other languages.” C. S. Peirce, the quantum measurement logic (the logic of knowledge and belief) Saitz was dedicated to teaching problem, and Bell’s theorem. -

Ill PROFMEX·ANUIES International Conference Scheduled for Tijuana in October

Number 6, Summer 1983 U NIVERSITY O F C ALIFORNI A C ONSORTIUM O N M EXICO & T HE U NITED S TATES BERKEL EY • D AVIS • IR VIN E • L os A NGELES • R IVERSIDE • SAN D IEGO • SAN FR ANCISCO • S AN TA B ARBARA • SAN TA CRUZ Ill PROFMEX·ANUIES International Conference Scheduled for Tijuana in October Hosted by CEFNOMEX representing the Carlos Monsivais (UNAM) ANUIES representatives to the Con Asociaci6n Nacional de Universidades e Jacinto Quirarte (UT San ference include Rafael Velasco lnstitutos de Ensenanza Superior and by Anton io) Fernandez (Secretario General UCLA and UC MEX US representing IV . Games Without Rules Ejecutivo), Antonio Gago Huguet PROFMEX , the Ill Conference of Mexican Moderator Manuel Garcia y Griego (Secretario Academico), and Ermilo J. and U.S. Universities on Border Studies (COLMEX) Marroquin (D irector de Relaciones will meet October 24 and 25 in Tijuana Panelists Lorenzo Meyer (COLMEX) lnternacionales y Becas) The theme of the conference is " Rules of Clark Reynolds (Stanford) Invited to close the conference are the Game in Border Life ," and attendance Ross Shipman (UTA) the Ambassadors of both countries , John is without restriction . Jesus Tamayo (CIDE) A. Gavin (Mexico City) and Jorge Invited to open the Conference are Jorge Vargas (Univ. of San Espinosa de los Reyes (Washington, D.C.) the Attorneys General of Mexico and the Diego) The conference is funded by US ICA United States, Sergio Garcia Ramirez Scott Whiteford (Michigan and ANUIES. and William French Smith. Smith wil l also State University) For more information, contact the con serve in his capacity as Regent of the Uni Other invited speakers include ference organizers: Jorge Bustamante, versity of California. -

Vol. 65 No. 21 January 29, 2019

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday January 29, 2019 Volume 65 Number 21 www.upenn.edu/almanac Penn Medicine: 25 Years of Charles Bernstein: Bollingen Prize for Poetry Integration, Innovation and Ideals University of Pennsylvania Professor Charles is the Donald T. Re- After 25 years, the combined mission of pa- Bernstein has been named the winner of the gan Professor of Eng- tient care, medical education and research that 2019 Bollingen Prize for American Poetry; it lish and Compara- defines Penn Medicine is a proven principle. As is is among the most prestigious prizes given to tive Literature in the Penn Medicine’s model has evolved over this American writers. School of Arts and Sci- quarter century, it has continually demonstrat- The Bollingen Prize is awarded biennially to ences (Almanac Febru- ed itself to be visionary, collaborative, resilient an American poet for the best book published ary 8, 2005). He is also and pioneering, all while maintaining Frank- during the previous two years, or for lifetime known for his transla- lin’s core, altruistic values of serving the greater achievement in poetry, by the Yale University tions and collabora- good and advancing knowledge. Library through the Beinecke Rare Book and tions with artists and Penn Medicine’s reach and impact would im- Manuscript Library. The Prize was originally libretti. With Al Filreis, press the lifelong teacher and inventor as well. conferred by the Library of Congress with funds Penn’s Kelly Family One of the first integrated academic health sys- established in 1948 by the philanthropist Paul Professor of English, tems in the nation, the University of Pennsylva- Mellon. -

Universities, Iowa Public Radio, and the Board Office

BOARD OF REGENTS AGENDA ITEM 5 STATE OF IOWA AUGUST 5, 2009 Contact: Brad Berg FY 2010 BUDGETS – UNIVERSITIES, IOWA PUBLIC RADIO, BOARD OFFICE Actions Requested: Consider approval of FY 2010: 1. Regent institutional budgets as presented on pages 5-9. 2. Iowa Public Radio budget as presented in Attachment D on page 23. 3. Board Office operating budget as shown in Attachment E on page 24. Executive Summary: Consistent with the Board’s strategic plan to demonstrate public accountability and effective stewardship of resources, all institutional budgets are approved annually by the Board. The FY 2010 budgets for the special schools were approved at the June 2009 meeting. In April, the Board considered key budgetary issues to provide guidance in the development of the FY 2010 institutional budgets. In June, the Board approved the institutional salary policies and received FY 2010 budget development updates from Iowa’s public universities, which included the projected application of one-time federal economic stimulus funding. The Board also adopted a resolution to hold salaries flat in FY 2010 for all non-bargaining unit employees with exceptions being approved by the institutional heads upon consultation with the Board Office. The Board is now asked to consider approval of the proposed budgets for the universities, Iowa Public Radio, and the Board Office. The Regent institutional budgets include two basic types of funds: General operating funds include operational appropriations, interest income, tuition and fee revenues, reimbursed indirect costs, and sales and services revenues. Some appropriations are designated for specific operating uses and cannot be used for other purposes. -

Remembering Mollie Tibbetts

The Daily Iowan THURSDAY, AUGUST 23, 2018 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 DAILY-IOWAN.COM 50¢ Remembering Mollie Tibbetts ABOVE: Community members gather to pay their respects to and remember Mollie Tibbetts during a vigil in Hubbard Park on Wednesday. Tibbetts vanished on July 18 in Brooklyn, Iowa. On Tuesday, authorities recovered her body and filed a murder charge against 24-year-old Poweshiek County resident Cristhian Rivera.Nick Rohlman/The Daily Iowan BOTTOM RIGHT: UI President Bruce Harreld observes a moment of silence during a vigil in memory of Tibbetts. Nick Rohlman/The Daily Iowan BOTTOM RIGHT: UI senior Haley Steele prays with friends during a vigil in memory of Tibbetts. Lily Smith/The Daily Iowan In the wake of Mollie Tibbetts’ death, Hawkeyes gathered to focus on her memory. BY CHARLES PECKMAN what made her so special was she was just in the University of Iowa community and [email protected] like anyone standing here — she loved to Dance Marathon, she was a prominent run, she loved Harry Potter, she loved the face on campus.” Hundreds of students clad in Dance Hawks, she loved her family, she loved her University Counseling Service Director Marathon and Hawkeye shirts gathered friends.” Barry Schreier said he was saddened by the in Hubbard Park on Wednesday evening UI student Breck Goodman said Tib- news of Tibbetts’ death, but he wishes the to remember Mollie Tibbetts, a University betts was her friend for many years and UI community could move forward with a of Iowa student who was found dead on cared deeply for those around her. -

The University of Iowa 2021-22 General Catalog 1

The University of Iowa 2021-22 General Catalog 1 The University of Iowa 2021-22 General Catalog The General Catalog provides information about academic programs at the University of Iowa, one of three universities governed by the Board of Regents, State of Iowa. The Catalog also provides links to supporting offices at the University, a list of administrative officers, an A-Z list of University of Iowa faculty members, a University calendar, and a link to the Code of Iowa for information regarding admission requirements and Iowa resident/nonresident standing. The General Catalog is published for informational purposes and should not be construed as the basis of a contract between a student and the University of Iowa. Every effort is made to provide information that is accurate at the time of publication. However, information on courses, curricula, fees, policies, regulations, and other matters is subject to change any time during the period for which the Catalog is in effect. For PDF versions of archived back editions, visit Archive on the Catalog website. The General Catalog is produced by the Office of the Registrar. Your comments and suggestions are welcome. Questions concerning the Catalog may be directed to the Office of the Registrar at [email protected]. The University of Iowa is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission. The University is a member of the Association of American Universities and is associated with Indiana, Michigan State, Northwestern, Ohio State, Pennsylvania State, Purdue, and Rutgers Universities and the Universities of Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska-Lincoln, and Wisconsin-Madison in the Big Ten Conference. -

Gophers Visit Iowa, Sniff Roses Cougars, J-Hawks Triumph DONT WOLF IT DOWN

I The Cedar Rapids Gazette: Fri., Nov. 3, 1967 21 Gophers Visit Iowa, Sniff Roses Red Peppers Mike for Ed Podolak-less By Gus Schrader Mike Cilek (left), inexperi enced soph from Iowa City, Hawks Use to seek a combination that can stop other will replace Eddie Podolak News Managing? teams. Iowa has given up an average of 409 (right) as Iowa's quarterback Soph Cilek E HADN’T seen Punchy Fisteras all yards per game so far. against Minnesota Saturday. “I think I got the answer,” Punchy said, Offensive Lineups week. He came in wearing a black eye. Podolak is out indefinitely W .starting for the door. “Iowa’s defense would IOWA MINNESOTA He promptly explained it happened Hallo Al Bream Chip Litten with a cracked rib. ween while bobbing for olives. He found outbe a blame site better if they hadn’t lost that Mike Phillips Ezell Jones tackle, John Evenden, who got knocked off Jeff Newland Andy Brown about swizzle sticks. Paul Usinowici Steve Lundeen by the books just before the first game. He Jon Meskimen Dick Enderle “Hey,” barked Punchy, “how' come this Mel Morris John Williams was the biggest guy on the squad at 270. Paul L aave9 Chas. Sanders Iowa football coach comes out like a flat Mike Cilek Curt Wilson “Did you see the way this Evenden went Si McKinnie George Kemp footed floogie and tells Minnesota and every Barry Crees Hubie Bryant through the wall of students in front of the Tim Sullivan Jim C arter body else his star quarterback, Eddie Podo Iowa Union Wednesday? I’ll bet ol’ Nagel Defensive Lineups lak, is hurt and can't play Saturday? We would like to have a pass rush like that on LE—Scott Miller LE—Bob Stein coulda fooled ’em—made ’em get ready lor LT—Rich Stepanek LT—R. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Recent Acquisitions. Catalogue 286 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.reeseco.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

Teh-Yuan Ho, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Teh-Yuan Ho, Ph.D. Department of Animal Sciences Tel: 848-932-6328 School of Environmental and Biological Sciences Fax: 732-932-6996 Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Foran Hall, 59 Dudley Road, Rm 126 [email protected] New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8525 animalsciences.rutgers.edu EDUCATION 1991 Ph.D., Plant Biology Rutgers University 1986 M.S., Biology University of Iowa 1979 B.S., Agronomy National Taiwan University PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2013-Present Research Associate Department of Animal Sciences, Rutgers University 2012 Visiting Scholar Institute of Molecular Biology, National Chung-Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan 2011 Plant Biologist USDA, Center for Plant Health Science and Technology (CPHST) 2003-2011 Research Associate Department of Animal Sciences, Rutgers University 2002-2003 Research/Teaching Specialist School of Public Health, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) 1995-2000 Research/Teaching Specialist Department of Environmental and Community Medicine, UMDNJ 1994-1995 Research Scientist Department of Developmental Chemotherapy, Memorial Sloan-Kettering 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Cancer Center 1991-1993 Postdoctoral Research Fellow Department of Pathology, Fox Chase Cancer Center 1986-1991 Teaching Assistant Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, Rutgers University 1983-1986 Teaching Assistant Department of Biology, The University of Iowa PUBLICATIONS 1. Bagnell, C., Ho, TY., George, A., Wiley, A.A., Miller, D., Bartol, F. (2017) Maternal Lactocrine Programming of Porcine Reproductive Tract Development. Mol Reprod Dev. 84:957-968. 2. Ho, TY., Rahman, K M., Camp M E., Wiley, A A., Bartol, F F., Bagnell C. (2016) Timing and duration of nursing from birth affect neonatal porcine uterine matrix metalloproteinase 9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1. -

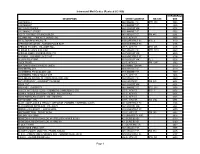

Intramural Mail Codes (Revised 9/21/09) DESCRIPTION STREET

Intramural Mail Codes (Revised 9/21/09) INTRAMURALC DESCRIPTION STREET ADDRESS RM./STE. ODE 3440 MARKET 3440 MARKET ST. STE. 300 3363 3440 MARKET 3440 MARKET ST. 3325 3601 LOCUST WALK 3601 LOCUST WK. 6224 3701 MARKET STREET 3701 MARKET ST. 5502 ACCTS. PAYABLE - FRANKLIN BLDG. 3451 WALNUT ST. RM. 440 6281 ADDAMS HALL - FINE ARTS UGRAD. DIV. 200 S. 36TH ST. 3806 ADDICTION RESEARCH CTR. 3900 CHESTNUT ST. STE. 5 3120 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION - SANSOM PLACE EAST 3600 CHESTNUT ST. 6106 AFRICAN STUDIES - WILLIAMS HALL 255 S. 36TH ST. STE. 645 6305 AFRICAN STUDIES, CTR. FOR 3401 WALNUT ST. STE. 331A 6228 AFRICAN-AMERICAN RESOURCE CTR. 3537 LOCUST WK. 6225 ALMANAC - SANSOM PLACE EAST 3600 CHESTNUT ST. 6106 ALUMNI RELATIONS 3533 LOCUST WK. FL. 2 6226 AMEX TRAVEL 220 S. 40TH ST RM. 201E 3562 ANATOMY/CHEMISTRY BLDG. (MED.) 3620 HAMILTON WK. 6110 ANNENBERG CTR. 3680 WALNUT ST. 6219 ANNENBERG PSYCHOLOGY LAB 3535 MARKET ST. 3309 ANNENBERG PUBLIC POLICY CTR. 202 S. 36TH ST. 3806 ANNENBERG SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION - ASC 3620 WALNUT ST. 6220 ANTHROPOLOGY - UNIVERSITY MUSEUM 3260 SOUTH ST. RM. 325 6398 ARCH, THE 3601 LOCUST WK. 6224 ARCHIVES, UNIVERSITY 3401 MARKET ST. STE. 210 3358 ARESTY INST./EXEC. EDUC.- STEINBERG CONFERENCE CTR. 255 S. 38TH ST. STE. 2 6356 ASIAN & MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES - WILLIAMS HALL 255 S. 36TH ST. 6305 ASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES - WILLIAMS HALL 255 S. 36TH ST. 6305 ASTRONOMY - DRL 209 S. 33RD ST. RM. 4N6 6394 AUDIT, COMPLIANCE & PRIVACY, OFFICE OF (FORMERLY INTERNAL AUDIT) 3819 CHESTNUT ST. 3106 BEN FRANKLIN SCHOLARS - THE ARCH 3601 LOCUST WK. -

2018 National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program

National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Listing Members listed in red are part of the National Park Service (NPS) Alabama Edward T. Sheldon Burial Site at Mobile Evergreen Cemetery Wallace Turnage Historic Marker Connecticut Arizona Hartford Tempe Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Passage on the UGRR: A Photographic New London Journey New London Custom House Arkansas Delaware Bluff City Camden Poison Spring Battle Site Camden Friends Meeting House Helena-West Helena Dover Civil War Helena Tour Delaware Public Archives Freedom Park Delaware State House Pine Bluff John Dickinson Plantation Battle of Pine Bluff Audio Tour Star Hill Historical Society Museum New Castle California New Castle Court House Napa Odessa Mary Ellen Pleasant Burial Site Appoquinimink Friends Meeting House Riverside and Cemetery Footsteps to Freedom Study Tour Corbit-Sharp House Sacramento Seaford California State Library Tilly Escape Site, Gateway to Freedom: San Francisco Harriet Tubman's Daring Route through Harriet Tubman: Bound for the Promised Seaford, DE Land Jazz Oratorio Wilmington Meet Mary Pleasant/Oh Freedom Historical Society of Delaware Saratoga Long Road to Freedom: The Mary A. Brown Burial Site Underground Railroad in Delaware Sonora Rocks- Fort Christina State Park Old Tuolumne County Courthouse Thomas Garrett House Site Tubman Garrett Riverfront Park and Colorado Market Street Bridge Colorado Springs Wilmington Friends Meetinghouse and Cemetery District of Columbia Fort Mose: Flight to Freedom: Annual African -

The "Literati" at Iowa in the Twenties

The "L itera ti" at Iowa in the Twenties CHARLTON LAIRD It was a no-win question, as I well knew. The “I” was a beginning graduate student at The University of Iowa in the autumn of 1925 who had come to be examined on a trial bibliography for a pro posed thesis and to endure whatever else the instructor in “Bibliog raphy and Method” might propose by way of purgatorial initiation. The questioner was Professor Thomas A. Knott, with varying de grees of affection known as “Tommy,” who was soon to become managing editor of the New International Dictionary, second edi tion, although none of us knew this as yet, not even Tommy. He was deeply devoted to scholarship, had a thunderous voice, and a prognathous jaw. I could imagine a deity, absorbed in matters of greater moment, absentmindedly tossing into the mixture that was to become Tommy Knott enough mandible for two jaw-jutting hu mans. “You have made the acquaintance of Mr. Cross’s little book?” he asked. “Mr. Cross’s little book” was Tom Peete Cross, Bibliographical Guide to English Studies, like Tommy himself a product of the Uni versity of Chicago. To slight it was lèse majesté. But what could I say? If I implied that I had gone over Cross with such care as I could muster—which I had—my scraps of learning would have been inundated in Tommy’s all-submerging knowledge. If I said I had been too busy to give the masterpiece the attention it deserved, and would eventually get, something would have hap pened, although I could not envisage what.