1 Jimmy Carter: a Man on a Mission an Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Freeman April 1953

APRIL 20, 1953 Russians Are People Eugene Lyons Decline of the Rule of Law F. A. Hayek The Battle Against Print Flora Rheta Schreiber Red China's Secret Weapon Victor Lasky Santayana: Alien in the World Max Eastman The Reading Company at its huge coal terminal near Perth Amboy handles as much as 4,000,000 tons annually. Most of this coal is distributed to docks in New York City and Brooklyn in 10,000-ton barges. Three new tugs powered with Fairbanks-Morse Diesels and equipped throughout with F-M Generators, Pumps and Motors are setting new records for speed and economy in this important task. Fairbanks, Morse & Co., Chicago 5, Illinois FAIRBANKS·MORSE a name worth remembering when you want the best DIESEL AND DUAL FUEL ENGINES • DIESEL LOCOMOTIVES • RAIL CARS • ELECTRICAL MACHINERY PUMPS • SCALES • HOME WATER SERVICE EQUIPMENT • FARM MACHINERY • MAGNETOS THE A Fortnightly Our Contributors For VICTOR LASKY, well-known journalist and spe cialist on Communism, won national renown in Individualists 1950 as co-author of the best-selling Seeds of reeman Treason. He i's editor of Spadea Syndicates. Editor HENRY HAZLITT EUGENE LYONS is particularly equipped to know Managing Editor FLORENCE NORTON and understand the Russian people, being him self a native of Russia and having spent many years as a correspondent in Moscow. Author of a number of books about the Soviet Union, including a biography of Stalin, he is now Contents VOL. 3, NO. 15 APRIL 20, 1953 working on a book tentatively entitled "Our Secret Weapon: the Russian People." . Editorials FLORA RHETA SCHREIBER is exceptionally quali The Fortnight. -

The Freeman May 1953

How to Integrate Europe The Fallacy in the Schuman Plan Wilhelm Ropke Russia's Three Bears Maneuvers 0/ Malenkov, Beria, and Bulganin Alexander Weissberg Peace Without Victory? An Editorial We built our own Pikes Peaks to IJn.;t"nlJlJrJlJtter car tmnsmissions THEY'RE called-in engineering language- formance of General Motors famous automatic Uelectronically variable dynamometers." And transmissions-Powerglide in Chevrolet; Hydra. -when this picture was taken-a transmission was Matic in Pontiac, Oldsmobile and Cadillac; being given the works under precisely the same Twin·Turbine Dynaflow in Buick. Not to mention conditions it would meet on a Pikes Peak climb, GM's automatic Army truck and tank transmis· including every single hairpin turn and road sions now proving their worth in Korea. grade. Here, then, is a typical example of the way GM What's more, the performance of the transmission engineers make use of every available material, is recorded even more exact!y than it could ever every practical method-even develop new mate· be on an actual trip up the mountain. rials and new methods - to build better, more Result: more knowledge added to the fund of economical products for you. In fact, it is this information about automatic transmissions which continuous engineering ingenuity and resource· our engineers have been uncovering since back in fulness which make the key to a Generttl Motors 1927. And a continuous improvement in the per. car-your key to greater value. GENERAl MOTORS "Your Key to Greater Value-the Key to a General Motors Car" CHEVROLET • PONTIAC • OLDSMOBILE • BUICK • CADILLAC • All with Body by Fisher • GMC TRUCK & COACH THE A. -

Edwin Guthman Oral History Interview – JFK #2, 2/24/1968 Administrative Information

Edwin Guthman Oral History Interview – JFK #2, 2/24/1968 Administrative Information Creator: Edwin Guthman Interviewer: John F. Stewart Date of Interview: February 24, 1968 Place of Interview: Los Angeles, CA Length: 38 pp. Biographical Note Guthman, Editor, Seattle Times (1947-1961); Director of Public Information, Department of Justice (1961-1964); press assistant to Robert F. Kennedy [RFK] (1964-1965) discusses the press coverage of civil rights during the Kennedy Administration, RFK’s relationship with the press, and Guthman’s involvement in the investigation of James R. Hoffa, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed August 22, 1991, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Reactions of Congress to the Alger Hiss Case, 1948-1960

Soviet Spies and the Fear of Communism in America Reactions of Congress to the Alger Hiss Case, 1948-1960 Mémoire Brigitte Rainville Maîtrise en histoire Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Brigitte Rainville, 2013 Résumé Le but de ce mémoire est de mettre en évidence la réaction des membres du Congrès des États-Unis dans le cadre de l'affaire Alger Hiss de 1948 à 1960. Selon notre source principale, le Congressional Record, nous avons pu faire ressortir les divergences d'opinions qui existaient entre les partisans des partis démocrate et républicain. En ce qui concerne les démocrates du Nord, nous avons établi leur tendance à nier le fait de l'infiltration soviétique dans le département d'État américain. De leur côté, les républicains ont profité du cas de Hiss pour démontrer l'incompétence du président Truman dans la gestion des affaires d'État. Il est intéressant de noter que, à la suite de l'avènement du républicain Dwight D. Eisenhower à la présidence en 1953, un changement marqué d'opinions quant à l'affaire Hiss s'opère ainsi que l'attitude des deux partis envers le communisme. Les démocrates, en fait, se mettent à accuser l'administration en place d'inaptitude dans l'éradication des espions et des communistes. En ayant recours à une stratégie similaire à celle utilisée par les républicains à l'époque Truman, ceux-ci n'entachent toutefois guère la réputation d'Eisenhower. Nous terminons en montrant que le nom d'Alger Hiss, vers la fin de la présidence Eisenhower, s'avère le symbole de la corruption soviétique et de l'espionnage durant cette période marquante de la Guerre Froide. -

Robert F. Kennedy's Dissent on the Vietnam War—I966

»-r /Jo, 5^0 A STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVE: ROBERT F. KENNEDY'S DISSENT ON THE VIETNAM WAR—I966-I968 Craig W. Cutbirth A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1976 An'nrnvprl hv T)r»r».toral nmrtmi ttee* i q ABSTRACT The Vietnam war -was one of the most hitter and divisive issues of the turbulent 1960’s. One American leader -who interacted with this issue was Robert F. Kennedy, United States Senator from New York. He was an ambitious man who had been the second most powerful man in the country during the Administration of John F. Kennedy. He was an acknowledged presidential aspirant. His actions and pronouncements attracted widespread attention—a source of potential benefit and danger for him. Kennedy planned his statements on the war with the utmost caution. He was particularly aware of the consequences of a personal break between himself and President Iyndon B. Johnson, wham Kennedy disliked and mistrusted. Accordingly, this study began with the assumption that Kennedy's planning involved the creation of a strategy through which he approached the Vietnam ,issue. Three of Kennedy's anti-war pronouncements were examined in this study. Each was considered an expression of Kennedy's rhetorical strategy. The nature of strategy was an object of some attention in this study. It was noted that the term has been used in a seemingly-contradictory manner. Accordingly, an attempt was made to clarify the nature of rhetorical strategy. It was determined that strategy is created to achieve some goal, and is implemented by certain tactics designed to energize audience support for the li rhetors position, thus achieving the desired goal. -

Eastland Collection File Series 4: Legislative Files Subseries 11: Internal Security Subcommittee Library

JAMES O. EASTLAND COLLECTION FILE SERIES 4: LEGISLATIVE FILES SUBSERIES 11: INTERNAL SECURITY SUBCOMMITTEE LIBRARY The U.S. Senate eliminated the Internal Security Subcommittee in 1977. In 1977-78, Senator James O. Eastland began transferring his congressional papers to the University of Mississippi. Among the items shipped were publications from the subcommittee’s library. Due to storage space concerns and the wide availability of many titles, the volumes were not preserved in toto. However, this subseries provides a complete bibliographic listing of the publications received as well as descriptions of stamps, inscriptions, or enclosures. The archives did retain documents enclosed within the Internal Security Subcommittee’s library volumes and these appear in Box 1 of this subseries. The bibliographic citation that follows will indicate the appropriate folder number. Call numbers and links to catalog records are provided when copies of the books are in the stacks of the J.D. Williams Library or Special Collections. Researchers should note that these are not necessarily the same copies that were in the Internal Security Subcommittee library or even the same editions. If the publications were previously held by the Internal Security Subcommittee, the library catalog record will note James O. Eastland’s name in the collector field. 24th Congress of the CPSU Information Bulletin 7-8, 1971. Prague, Czechoslovakia: Peace and Socialism Publishers, [1971]. Enclosed: two advertisements from bookseller Progress Books. Enclosed items retained in Folder 1-1. Mildred Adams, ed. Latin America: Evolution or Explosion? New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1963. Stamped: “Received/Jun 3 1963/Int. Sec. S-Comm.” Call Number: F1414 C774 1962. -

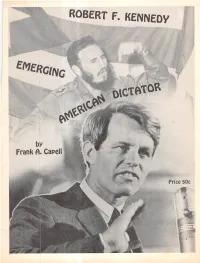

Robert F. Kennedy

ROBERT F. KENNEDY '.4?i V / by Frank A. CapeK Price 50c / * • 1 K* Copyright 1968 by FRANK A. CAPELL All Rights Reserved Published by the Herald of Freedc m Zarephath, New Jersey 08890 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Frank A. Capell is the editor ofThe HERALD ofFREEDON , a national anti-communist educational bi-weekly. Beginning as an undercover criminal nv(5siigator(tight-roper)for dis- trict attorneys and police commissioners, he later became Chi 5f| Investigator of the West- Chester County (N.Y.) Sheriffs Office. In this capacity he ejsta )lished a Bureau of Subver- sive Activities. He supervised the investigation of over five t 4sand individuals and organ- izations, including Nazis, Fascists and Communists, on behallf c the F.B.I, in many cases. During World War II, he served as a civilian investigator ovjerstak doing intelligence work. The author has been fighting the enemies of our country for twenty-nine years in of- ficial and unofficial capacities. As a writer, lecturer, instrucior researcher and investigator, he has appeared before audiences and on radio and television fiioni c^astto coast. Hemaintains files containing the names of almost two million people who liiaye aided the International Communist Conspiracy. Mr. Capell is the author of "Freedc m [sj Up To You" (now out of print), "The Threat From Within," "Treason is the Reason," "T le Strange Death of Marilyn Monroe," and "The Strange Case of Jacob Javits." His biogjrap tiy has appeared for many years in "Who's Who in Commerce and Industry." INTRODUCTION The knights of Camelot are on the march again On this occasion Kennedy was reported as stat since Prince Bobby has announced he will make his ing: move to restore the Kennedy Dynasty in 1968 in "We should INTENSIFY DISARMAMENTEFFORTS stead of 1972. -

Presidential Agendas and Legislative Success: the Carter Administration's Management Style

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1995 Presidential agendas and legislative success: The Carter administration's management style Erik S. Root The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Root, Erik S., "Presidential agendas and legislative success: The Carter administration's management style" (1995). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8589. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8589 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. B66T, El^l I I I Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University ofIVIONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. * * Please check T g 5" or "No" and provide si^ature * * T Author's Signature D ate 7- Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PRESIDENTIAL AGENDAS AND LEGISLATIVE SUCCESS: THE CARTER ADMINISTRATION'S MANAGEMENT STYLE by ERIK S. ROOT B.A. -

Fourth Estate and Chief Executive (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 12, folder “Fourth Estate and Chief Executive (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 12 of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library -----=-==--- FOURTH ESTATE and II II Nary McGrory II I Richard 11ilhous N:Lxon Hy Parents CON TEN'@ II . II INTRODUCTION ••••••••••.••••••••••••••••.• .......................... 1_ IdHA.PTER O!~E: PRIVATE • .......- • .-. -.-..................................... 6 •.,,. Presidential reading habits(6)--John F. Kennedy(8)--Dwight D. 11 1 Eisenhower and the press(16)--Kennedy(19)-11News Hanagement (34)-- , Duty and Friendship(42)--~don B. Johnson(45)--0rigins of the l Credibility Gap(.51)--Richard M. Nixon(61) 1 il . I • . .. : . .. ICHAPTER TWO. PUBUC .l •••••••••••••.••••••••••••••••••••.•••• • ••••••• 62 .A.FORNAT Stating. the problem(63)-0pening Statements(65)--Planted Questions(75)--Reporters Not Prepared(81)-Reporter1s Bad Technique(85)--Unasked Questions(90)--Closing the conference(9&) I IB. TECHNOLOGY · . I Truman's tiorst-Case &8 )--Nixon 1 s Blunder ( 102)--Changing the ·~ Record(104 )--Hoti.ld ~Ike' Continue the Conference ?(106 )-- Transcripts and Broadcasts(169)--Sound 11ovies(110)--Live TV{15) .. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School Certificate for Approving The

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jewerl Maxwell Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________ Director Dr. Ryan Barilleaux __________________________________________ Reader Dr. Augustus Jones __________________________________________ Reader Dr. John Rothgeb __________________________________________ Graduate School Representative Dr. Allan Winkler Abstract In his 2001 text With a Stroke of a Pen, Kenneth Mayer contended, “Affirmative action – or the practice of granting preferences in employment, contracting, or education on the basis of race and gender – is largely a creature of executive action” (202). In spite of the substantial role played by America’s chief executives in enactment of such policies, with the exception of Mayer’s brief analysis in his chapter on civil rights, explanations regarding how and why presidents have enacted such policies have eluded presidency scholars. Thus, the primary objective of this study is to identify and explain the answer to the following questions: 1) To what extent have modern presidents used executive orders to establish federal affirmative action policy in the realm of equal employment opportunity for underrepresented groups in American society, prior to actions taken by other governmental institutions? 2) What factors explain presidential decision-making regarding executive orders pertaining to equal employment opportunity for underrepresented groups? To accomplish -

INSTITUTIONS of PUBLIC MEMORY the Legacies of German and American Politicians

I n s t i t u t i o n s o f The Legacies of P u b l German and American i c M Politicians e m o r This volume emerged from the conference Access—Presentation— y Memory: The Presidential Libraries and the Memorial Foundations of German Politicians held at the German Historical Institute, Washington, D.C. Facilitating dialogue across disciplinary boundaries as well as the Atlantic, it brought representatives from the U.S. presidential libraries, the 5H[PVUHS(YJOP]LZHUK[OLÄ]L.LYTHUTLTVYPHSMV\UKH[PVUZ[VNL[OLY with professors, archivists, and members of public interest groups. The selected essays offer unique insights into the legal, cultural, and historical PUÅ\LUJLZVU[OLMVYTHSJVUZ[Y\J[PVUVMWVSP[PJHSSLNHJPLZ Astrid M. Eckert was a research fellow at the German Historical Institute, Washington, D.C., from 2002 to 2005. In 2006, she joined the faculty at Emory Edited by University in Atlanta as Assistant Professor of Modern European History. Astrid M. Eckert A s t r i d M . Institutions E c k e r t GERMAN of Public Memory HISTORICAL INSTITUTE The Legacies of German and American Politicians INSTITUTIONS OF PUBLIC MEMORY The Legacies of German and American Politicians Edited by Astrid M. Eckert German Historical Institute Washington, DC FM i — Title page GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC INSTITUTIONS OF PUBLIC MEMORY THE LEGACIES OF GERMAN AND AMERICAN POLITICIANS LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Introduction: The Institutionalization of Political Legacies in Germany and the United States 1 Astrid M. Eckert With a Whiff of Royalism: Exhibiting Biographies in American Presidential Libraries 9 Thomas Hertfelder Visiting Presidential and Chancellor Museums: An American Perspective 33 John C. -

Robert F. Kennedy As a Liberal Icon

The Once and Future King: Robert F. Kennedy as a Liberal Icon Anne Mørk University of Southern Denmark Abstract: This article examines Robert F. Kennedy’s status as an icon to the American public and both liberals and conservatives. The difficulty in categorizing Kennedy’s complex political beliefs within just one of many liberal traditions is key to under- standing his popularity with various—and often opposing—groups within American politics. Whereas conservatives favor Kennedy’s tough attitude on law-and-order, liberals admire Kennedy’s electoral appeal and ability to unite voters. However, the American people have adopted Kennedy as a non-partisan icon in the tradition of Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and John F. Kennedy. Starting with Kenne- dy’s death, the American people remembered him as a martyr of American democracy, justice, and equality. In the new millennium, Kennedy has frequently been presented in the media and political rhetoric as tough, but compassionate, and thereby as a liberal icon for the ages. Keywords: Robert F. Kennedy—liberalism—conservatism—presidential elections— assassination—John F. Kennedy—Democratic Party Introduction In his lifetime, Robert F. Kennedy was an immensely controversial figure, either deeply resented or passionately admired by voters, scholars, journal- ists, and fellow politicians alike. After his assassination in June 1968, his popularity skyrocketed and the critical voices lessened, although they did 30 American Studies in Scandinavia, 44:2 not disappear. The critical voices, mostly