The Challenges of Institutionalizing Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh Assessment

BANGLADESH ASSESSMENT October 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 – 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY General 2.1 – 2.3 Languages 2.4 Economy 2.5 – 2.6 III HISTORY Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 3.1 – 3.4 1972-1982 3.5 – 3.8 1983 – 1990 3.9 – 3.15 1991 – 1996 3.16 – 3.21 1997 - 1999 3.22 – 3.32 January 2000 - December 2000 3.33 – 3.35 January 2001 – October 2001 3.36 – 3.39 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE 4.1 POLITICAL SYSTEM Constitution 4.1.1 – 4.1.3 Government 4.1.4 – 4.1.5 President 4.1.6 – 4.1.7 Parliament 4.1.8 – 4.1.10 4.2 JUDICIAL SYSTEM 4.2.1 – 4.2.4 4.3 SECURITY General 4.3.1 – 4.3.4 1974 Special Powers Act 4.3.5 – 4.3.7 Public Safety Act 4.3.8 2 V HUMAN RIGHTS 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 – 5.1.3 5.2 GENERAL ASSESSMENT Torture 5.2.1 – 5.2.3 Police 5.2.4 – 5.2.9 Supervision of Elections 5.2.10 – 5.2.12 Human Rights Groups 5.2.13 – 5.2.14 5.3 SPECIFIC GROUPS Religious Minorities 5.3.1 – 5.3.6 Biharis 5.3.7 – 5.3.14 Chakmas 5.3.15 – 5.3.16 Rohingyas 5.3.17 – 5.3.18 Ahmadis 5.3.19 – 5.3.20 Women 5.3.21 – 5.3.32 Children 5.3.33 – 5.3.36 Trafficking in Women and Children 5.3.37 – 5.3.39 5.4 OTHER ISSUES Assembly and Association 5.4.1 – 5.4.3 Speech and Press 5.4.4 – 5.4.5 Travel 5.4.6 Chittagong Hill Tracts 5.4.7 – 5.4.10 Student Organizations 5.4.11 – 5.4.12 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 5.4.13 Domestic Servants 5.4.14 – 5.4.15 Prison Conditions 5.4.16 – 5.4.18 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY III HISTORY 3.2 East Pakistan became dissatisfied with the distant central government in West Pakistan, and the situation was exacerbated in 1952 when Urdu was declared Pakistan's official language. -

The Challenges of Institutionalising Democracy in Bangladesh† Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University

ISAS Working Paper No. 39 – Date: 6 March 2008 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg The Challenges of Institutionalising † Democracy in Bangladesh Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University Contents Executive Summary i-iii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Challenges of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: A Global Discourse 4 3. The Challenge of Organising Free and Fair Elections 7 4. The Challenge of Establishing the Rule of Law 19 5. The Challenge of Guaranteeing Civil Liberties and Fundamental Freedoms 24 6. The Challenge of Ensuring Accountability 27 7. Conclusion 31 Appendix: Table 1: Results of Parliamentary Elections, February 1991 34 Table 2: Results of Parliamentary Elections, June 1996 34 Table 3: Results of Parliamentary Elections, October 2001 34 Figure 1: Rule of Law, 1996-2006 35 Figure 2: Political Stability and Absence of Violence, 1996-2006 35 Figure 3: Control of Corruption, 1996-2006 35 Figure 4: Voice and Accountability, 1996-2006 35 † This paper was prepared for the Institute of South Asian Studies, an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. ∗ Professor Rounaq Jahan is a Senior Research Scholar at the Southern Asian Institute, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University. She can be contacted at [email protected]. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bangladesh joined what Samuel P. Huntington had called the “third wave of democracy”1 after a people’s movement toppled 15 years of military rule in December 1990. In the next 15 years, the country made gradual progress in fulfilling the criteria of a “minimalist democracy”2 – regular free and contested elections, peaceful transfer of governmental powers as a result of elections, fundamental freedoms, and civilian control over policy and institutions. -

Bangladesh Page 1 of 20

Bangladesh Page 1 of 20 Bangladesh Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2007 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 11, 2008 Bangladesh is a parliamentary democracy of 150 million citizens. Khaleda Zia, head of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), stepped down as prime minister in October 2006 when her five-year term of office expired and transferred power to a caretaker government that would prepare for general elections scheduled for January 22. On January 11, in the wake of political unrest, President Iajuddin Ahmed, the head of state and then head of the caretaker government, declared a state of emergency and postponed the elections. With support from the military, President Ahmed appointed a new caretaker government led by Fakhruddin Ahmed, the former Bangladesh Bank governor. In July Ahmed announced that elections would be held by the end of 2008, after the implementation of electoral and political reforms. While civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces, these forces frequently acted independently of government authority. The government's human rights record worsened, in part due to the state of emergency and postponement of elections. The Emergency Powers Rules of 2007 (EPR), imposed by the government in January and effective through year's end, suspended many fundamental rights, including freedom of press, freedom of association, and the right to bail. The anticorruption drive initiated by the government, while greeted with popular support, gave rise to concerns about due process. For most of the year the government banned political activities, although this policy was enforced unevenly. -

Who Did Not Registra

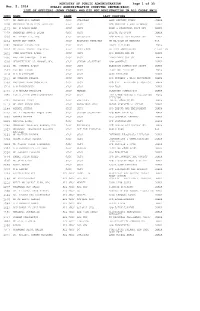

MINISTRY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Page 1 of 35 Mar. 2, 2016 PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION COMPUTER CENTRE(PACC) LIST OF OFFICERS (ADMN CADRE) WHO DID NOT REGISTRATION IN ALL CADRE PMIS IDNO NAME RANK LAST POSTING 1041 MD MAHFUZUR RAHMAN SECY CHAIRMAN LAND REFORMS BOARD DHAKA 1096 MOHAMMAD MOINUDDIN ABDULLAH SECY SECY M/O HOUSING & PUBLIC WORKS DHAKA 1171 DR. M ASLAM ALAM SECY SECY BANK & FINANCIAL INST DIV DHAKA 1229 KHANDKER ANWRUL ISLAM SECY SECY BRIDGE DIVISION DHAKA 1230 MD EBADOT ALI, NDC SECY OSD(SECY) M/O PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION DHAKA 1264 BARUN DEV MITRA SECY ECONOMIC MINISTER UN MISSION IN NEWYORK USA 1381 MONOWAR ISLAM, NDC SECY SECY POWER DIVISION DHAKA 1394 MD ABDUL MANNAN HOWLADER SECY HIGH COMM BD HIGH COMMISSION MAURITIUS 1431 SYED MONJURUL ISLAM SECY SECY M/O HEALTH AND FW DHAKA 1456 BHUIYAN SHAFIQUL ISLAM SECY SECY PRESIDENTS OFFICE DHAKA 1520 HEDAYETULLAH AL MAMOON, NDC SECY SENIOR SECRETARY M/O COMMERCE DHAKA 1521 MD. SIRAZUL ISLAM SECY SECY ELECTION COMMISSION SECTT DHAKA 1569 TARIQUL ISLAM SECY SECY PLANNING DIVISION DHAKA 1610 M A N SIDDIQUE SECY SECY ROAD DIVISION DHAKA 1653 MD HUMAYUN KHALID SECY SECY M/O PRIMARY & MASS EDUCATION DHAKA 1709 KHURSHED ALAM CHOWDHURY SECY SECY M/O CIVIL AVIATION & TOURISM DHAKA 1710 A M BADRUDDUJA SECY SECY M/O FOOD DHAKA 1733 S M GHULAM FAROOQUE SECY MEMBER PLANNING COMMISSION DHAKA 1876 FARID UDDIN AHMED CHOWDHURY SECY SECY IMPLE/MONITORING & EVALUATION DHAKA DIVISION 2007 MUSHFEKA IKFAT SECY CHAIRMAN TARIFF COMMISSION DHAKA 2113 MD ABUL KALAM AZAD SECY PRINCIPAL SECY PRIME MINISTER`S OFFICE DHAKA 2148 MIKAIL SHIPAR SECY SECY M/O LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT DHAKA 2232 DR. -

Icmab 17Th Council Election February 07, 2020

ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION FEBRUARY 07, 2020 CENTRAL VOTER LIST CENTRAL VOTER LIST ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION The Institute of Cost and Management Accountants of Bangladesh (ICMAB) ICMA Bhaban, Nilkhet, Dhaka-1205 CENTRAL VOTER LIST ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION FELLOW MEMBERS 1 F-0002 5 F-0030 Mr. Rafiq Ahmad FCMA Mr. A.B.M. Shamsuddin FCMA Executive Director Senior Financial Management Specialist T. K. Group of Industries Rural Transport Improvement Project-2 T.K. Bhaban (2nd floor) LGRD (World Bank Finance Project) 13, Kawran Bazar House # 289, Flat # A-3 Dhaka 1215 Road # 12, Block-A Bangladesh Bashundhara R/A Cell : 8801711566828 Dhaka E-mail : [email protected] Bangladesh Cell : 8801819252805 2 F-0016 E-mail : [email protected] Mr. Md. Afsarul Alam FCMA House No. 26 6 F-0032 Sonargaon Janapath (Chowrasta) Mr. D.P. Bhattacharyya FCMA Sector – 11 1403 Tropic Terrace Uttara Model Town FL 33903-5271 Dhaka 1230 United States of America (USA) Bangladesh Cell : 12396288687 Cell : 8801911216139 E-mail : [email protected] 3 F-0020 7 F-0034 Alhaj Md. Matior Rahman FCMA Mr. Md. Noor Baksh FCMA Makam-E-Mahmud, House # GA-117/2 House # 1, Road # 1, Block-B Middle Badda, Near Noor Moszid Palashpur, East Dania Gulshan, Dhaka 1212 Dhaka 1236 Bangladesh Bangladesh Cell : 8801778413531 Cell : 8801913805529 4 F-0027 8 F-0038 Mr. Md. Ishaque FCMA Mr. Muzaffar Ahmed FCMA Adviser President and CEO DBL Group Credit Rating Information and Services Ltd. Capita South Avenue (6th Floor) Nakshi Homes (4th floor) House # 50, Road # 3 6/1-A, Topkhana Road Gulshan Avenue Segunbagicha Gulshan- 1, Dhaka 1212 Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh Bangladesh Cell : 8801819213014 Cell : 8801713041913 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] Page 2 of 122 CENTRAL VOTER LIST ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION 9 F-0042 15 F-0057 Mr. -

In Countries of Written Constitutions the Courts Are Temples of Justice, the Judges Its Oracles

Martial Law, Judiciary and Judges 181 MARTIAL LAW, JUDICIARY AND JUDGES: TOWARDS AN ASSESSMENT OF JUDICIAL INTERPRETATIONS Sheikh Hafizur Rahman Karzon * Abdullah-Al-Faruque ** INTRODUCTION In countries of written constitutions the courts are regarded as temples of justice, the judges its oracles. Constitutional supremacy presupposes the existence of a strong neutral organ which would be able to prevent unconstitutional onslaught by the executive and legislature. In course of time judiciary has been developed and recognised as the guardian of the constitution. If executive or legislature desires to do something which is inconsistent with the provisions of the constitution, the judiciary has been empowered to undo the ill-design orchestrated by the executive or legislature. When an usurper unconstitutionally captures state apparatus, the judiciary is expected to act in the way as the constitution, supreme law of the land, directs. The judges are subject only to the constitution as they are oath bound to preserve, protect and defend it. They submit their allegiance and make themselves subservient to the constitution and (valid) law. Judiciary is expected to be the ultimate custodian of the constitution, but when an unconstitutional martial law regime captured power in a country the judiciary has seldom been able to stand by its oath. In most of cases, the judiciary became a passive spectator or a partner with the usurper's regime rather than a protector of the constitution and rule of law. Once upon a time the highest court of country treated de facto government as valid source of law which has been established by successful usurpation of power. -

Bangladesh in 2001: the Election and a New Political Reality?

BANGLADESH IN 2001 The Election and a New Political Reality? M. Rashiduzzaman Though some scattered incidents of violence took place, the Bangladesh election of October 1, 2001, was, relatively speaking, a peace- ful event, especially against the backdrop of galloping strife in the country in recent years. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and its three coalition partners won 216 seats in the 300-member Jatiya Sangshad (national parlia- ment), and Begum Khaleda Zia became prime minister of the new BNP-led government. Both the Election Commission and the constitutionally man- dated caretaker government earned admiration at home and abroad for con- ducting a successful poll and transferring power to the newly elected leaders. However, the Awami League (AL), the BNP’s predecessor as ruling party, accused the BNP and its partners of a “crude rigging” of the election in con- nivance with the nonpartisan interim government and the Election Commis- sion.1 Periodic political and communal violence after the election forced the new government to promise an “intensive drive” against lawlessness, which included the dramatic move on Khaleda’s part of suspending the Chatra Dal Central committee of the BNP’s student front. 2 Confident after her landslide victory, Khaleda then made appeals to her political rivals for peace and coop- eration and called for all to work for the prosperity of Bangladesh. 3 M. Rashiduzzaman is Associate Professor in the Department of Politi- cal Science, Rowan University, New Jersey. Asian Survey , 42:1, pp. 183–191. ISSN: 0004–4687 2002 by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. -

Issue Paper BANGLADESH POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS DECEMBER 1996-APRIL 1998 May 1998

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/POLITICAL... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper BANGLADESH POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS DECEMBER 1996-APRIL 1998 May 1998 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents MAP GLOSSARY 1. INTRODUCTION 2. KEY POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS 2.1 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 2.2 Ganges Water Sharing Agreement 2.3 General Strikes and Restrictions on Rallies 2.4 Elections 2.5 Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) Peace Treaty 3. LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS 3.1 Law Reform Commission 3.2 Judicial Reform 1 of 27 9/16/2013 3:57 PM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/POLITICAL... 3.3 National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) 3.4 Special Powers Act (SPA) 4. OPPOSITION PARTIES 4.1 Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) 4.2 Jatiya Party (JP) 4.3 Jamaat-e-Islami (Jamaat) 5. FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS REFERENCES MAP See original. Source: UNHCR Refworld -

Convert JPG to PDF Online

Withheld list SL # Roll No 1 12954 2 00220 3 00984 4 05666 5 00220 6 12954 7 00984 8 05666 9 21943 10 06495 11 04720 1 SL# ROLL Name Father Marks 1 00002 MRINALINI DEY PARIJAT KUSUM PATWARY 45 2 00007 MD. MOHIUL ISLAM LATE. MD. NURUL ISLAM 43 3 00008 MD. SALAM KHAN RUHUL AMIN KHAN 40 4 00014 SYED AZAZUL HAQUE SAYED FAZLE HAQUE 40 5 00016 ROMANCE BAIDYA MILAN KANTI BAIDYA 51 6 00018 DIPAYAN CHOWDHURY SUBODH CHOWDHURY 40 7 00019 MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM MD. ABUL HASHEM 47 8 00021 MD. MASHUD-AL-KARIM SAHAB UDDIN 53 9 00023 MD. AZIZUL HOQUE ABDUL HAMID 45 10 00026 AHSANUL KARIM REZAUL KARIM 54 11 00038 MOHAMMAD ARFAT UDDIN MOHAMMAD RAMZU MIAH 65 12 00039 AYON BHATTACHARJEE AJIT BHATTACHARJEE 57 13 00051 MD. MARUF HOSSAIN MD. HEMAYET UDDIN 43 14 00061 HOSSAIN MUHAMMED ARAFAT MD. KHAIRUL ALAM 42 15 00064 MARJAHAN AKTER HARUN-OR-RASHED 45 16 00065 MD. KUDRAT-E-KHUDA MD. AKBOR ALI SARDER 55 17 00066 NURULLAH SIDDIKI BHUYAN MD. ULLAH BHUYAN 46 18 00069 ATIQUR RAHMAN OHIDUR RAHMAN 41 19 00070 MD. SHARIFUL ISLAM MD. ABDUR RAZZAQUE (LATE) 46 20 00072 MIZANUR RAHMAN JAHANGIR HOSSAIN 49 21 00074 MOHAMMAD ZIAUDDIN CHOWDHURY MOHAMMAD BELAL UDDIN CHOWDHURY 55 22 00078 PANNA KUMAR DEY SADHAN CHANDRA DEY 47 23 00082 WAYES QUADER FAZLUL QUDER 43 24 00084 MAHBUBUR RAHMAN MAZEDUR RAHMAN 40 25 00085 TANIA AKTER LATE. TAYEB ALI 51 26 00087 NARAYAN CHAKRABORTY BUPENDRA KUMER CHAKRABORTY 40 27 00088 MOHAMMAD MOSTUFA KAMAL SHAMSEER ALI 55 28 00090 MD. -

BANGLADESH ASSESSMENT October 2002

BANGLADESH COUNTRY ASSESSMENT October 2002 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM 1 CONTENTS 1 SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 – 1.4 2 GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.4 - General 2.1 - 2.3 - Languages 2.4 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.2 4. HISTORY 4.1 - 4.43 - Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 4.1 - 4.4 - 1972 -1982 4.5 - 4.8 - 1983 - 1990 4.9 - 4.15 - 1991 - 1996 4.16 - 4.21 - 1997 - 1999 4.22 - 4.31 - January 2000 - December 2000 4.32 - 4.34 - January 2001 - October 2001 4.35 - 4.37 - October 2001 to October 2002 4.38 - 4.44 5. THE STATE STRUCTURE Constitution 5.1 - 5.3 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 - 5.6 Political System 5.7 - 5.12 - Government 5.7 - 5.9 - Supervision of Elections 5.10 - 5.12 Judiciary 5.13 - 5.15 - Informal Systems of Justice and Village Courts 5.16 - Fatwas 5.17 - Legal Rights / Detentions 5.18 - 5.29 - Preventive Detention and its Legislative Framework 5.19 - The Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) 5.20 - 5.21 - The Special Powers Act (SPA) 5.22- 5.24 - Public Safety Act (PSA) 5.25 - Pre-trial Detention 5.26 - Bail 5.27 - Safe Custody 5.28 - Death Penalty 5.29 Internal Security 5.30 - 5.31 Prison Conditions 5.32 - 5.34 Military Service 5.35 Medical Services 5.36 - 5.38 Education System 5.39 - 5.43 2 6. HUMAN RIGHTS 6A. Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.26 Overview 6.1 - 6.3 Police and the Abuse of Human Rights 6.4 - 6.11 - Torture 6.5 - 6.6 - Politically-motivated Detentions 6.7 - Police Impunity 6.8 - 6.9 - Safe Custody 6.10 - Rape in Custody 6.11 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.12 - 6.17 Freedom of Religion 6.18 Freedom of Association and Assembly 6.19 - 6.20 Employment Rights 6.21 - 6.24 People Trafficking 6.25 Freedom of Movement 6.26 6B. -

Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons

Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons (BCPS) 67, Shaheed Tajuddin Ahmed Ave, Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh Registered Applicant list, FCPS Part-I Examination-January-2021 BMDC NoName Speciality 27180 K.M. ABU MUSA- Anaesthesiology 29499 MD. SHAMIM KABIR SIDDQUE - Anaesthesiology 31090 MUHAMMAD MUNIRUZZAMAN - Anaesthesiology 33423 FATEMA KALI- Anaesthesiology 33697 MOHAMMED NAFEES ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 36857 MD. ASHRAFUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 38885 SYADA MAHZABIN TAHER- Anaesthesiology 39412 MOSHARRAF HOSSAIN - Anaesthesiology 40130 MOHAMMAD MIZAN UDDIN EMRAN- Anaesthesiology 40501 NORUN NAHAR- Anaesthesiology 42327 SOHANA SEKANDER- Anaesthesiology 43996 MOHAMMED MAMUN MORSHED- Anaesthesiology 44910 SYED MAHBOOB ISHTIAQUE AHMAD- Anaesthesiology 45105 ARUP RATAN BARAI - Anaesthesiology 46053 MD. ABU BAKER SIDDIQUE- Anaesthesiology 46101 TAHMINA BHUIYAN- Anaesthesiology 46632 SUHANA FERDOUS- Anaesthesiology 47119 MOHD.SAIF HOSSAIN JOARDER- Anaesthesiology 47129 RICHARD D' COSTA- Anaesthesiology 47565 MD. GIAS KAMAL CHOWDHURY MASUM- Anaesthesiology 48289 S. M. NAZRUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 48601 TAPASHI CHOWDHURY- Anaesthesiology 48825 JANNATH ARA FERDOUS- Anaesthesiology 50720 EVANA SAMAD- Anaesthesiology 51277 MD. KHIZIR HOSSAIN- Anaesthesiology 52570 SHAHANAJ SARMIN - Anaesthesiology 52891 TASNUVA TANZIL- Anaesthesiology 53159 AFIFA FERDOUS- Anaesthesiology 53350 SHOHELE SULTANA- Anaesthesiology 55285 MUNMUN BARUA- Anaesthesiology 55431 MOHAMMAD ZOHANUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 55459 ASHRAFUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 55588 MANSURA -

Progress of Higher Education in Colonial Bengal and After -A Case Study of Rajshahi Colle.Ge

PROGRESS OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN COLONIAL BENGAL AND AFTER -A CASE STUDY OF RAJSHAHI COLLE.GE. (1873-1973) Thesis Submitted to the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. ( ( l r"<t •· (•(.j 1:'\ !. By Md. Monzur Kadir Assistant Professor of Islamic History Rajshahi College, Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Under the Supervision of Dr. I. Sarkar Reader in History University of North Bengal,· Darjeeling, West Bengal, India. November, 2004. Ref. '?:J 1B. s-4 C124 oqa4 {(up I 3 DEC 2005 Md. Monzur Kadir, Assistant Professor, Research 5 cholar, Islamic History, Department of History Rajshahi College, Uni~ersity of North Bengal Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Darjeeling, India. DECLARATION . I hereby declare that the Thesis entitled "PROGRESS OF HIGHER EDUc;ATION IN COLONIAL BENGAL AND AFTER- A CASE STUDY OF RAJSHAHI COLLEGE (1873-1973)," submitted by me for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of the University of North Bengal, is a record of research work done by me and that the Thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship and similar other titles. II · 8 "' (Jl~Mt ~~;_ 10. -{ (Md. Monzur Kadir) Acknowledgement------------ This dissertation is the outcome of a doctoral research undertaken at the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India. It gives me immense pleasure to place on record the great help and co-operation. I received from several persons and institutions during the preparation of this dissertation. I am already obliged to Dr. I. Sarkar, Reader in History. North Bengal University who acted as my supervisor and for his urqualified support in its planning and execution.