In Countries of Written Constitutions the Courts Are Temples of Justice, the Judges Its Oracles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh Assessment

BANGLADESH ASSESSMENT October 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 – 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY General 2.1 – 2.3 Languages 2.4 Economy 2.5 – 2.6 III HISTORY Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 3.1 – 3.4 1972-1982 3.5 – 3.8 1983 – 1990 3.9 – 3.15 1991 – 1996 3.16 – 3.21 1997 - 1999 3.22 – 3.32 January 2000 - December 2000 3.33 – 3.35 January 2001 – October 2001 3.36 – 3.39 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE 4.1 POLITICAL SYSTEM Constitution 4.1.1 – 4.1.3 Government 4.1.4 – 4.1.5 President 4.1.6 – 4.1.7 Parliament 4.1.8 – 4.1.10 4.2 JUDICIAL SYSTEM 4.2.1 – 4.2.4 4.3 SECURITY General 4.3.1 – 4.3.4 1974 Special Powers Act 4.3.5 – 4.3.7 Public Safety Act 4.3.8 2 V HUMAN RIGHTS 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 – 5.1.3 5.2 GENERAL ASSESSMENT Torture 5.2.1 – 5.2.3 Police 5.2.4 – 5.2.9 Supervision of Elections 5.2.10 – 5.2.12 Human Rights Groups 5.2.13 – 5.2.14 5.3 SPECIFIC GROUPS Religious Minorities 5.3.1 – 5.3.6 Biharis 5.3.7 – 5.3.14 Chakmas 5.3.15 – 5.3.16 Rohingyas 5.3.17 – 5.3.18 Ahmadis 5.3.19 – 5.3.20 Women 5.3.21 – 5.3.32 Children 5.3.33 – 5.3.36 Trafficking in Women and Children 5.3.37 – 5.3.39 5.4 OTHER ISSUES Assembly and Association 5.4.1 – 5.4.3 Speech and Press 5.4.4 – 5.4.5 Travel 5.4.6 Chittagong Hill Tracts 5.4.7 – 5.4.10 Student Organizations 5.4.11 – 5.4.12 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 5.4.13 Domestic Servants 5.4.14 – 5.4.15 Prison Conditions 5.4.16 – 5.4.18 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY III HISTORY 3.2 East Pakistan became dissatisfied with the distant central government in West Pakistan, and the situation was exacerbated in 1952 when Urdu was declared Pakistan's official language. -

The Challenges of Institutionalising Democracy in Bangladesh† Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University

ISAS Working Paper No. 39 – Date: 6 March 2008 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg The Challenges of Institutionalising † Democracy in Bangladesh Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University Contents Executive Summary i-iii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Challenges of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: A Global Discourse 4 3. The Challenge of Organising Free and Fair Elections 7 4. The Challenge of Establishing the Rule of Law 19 5. The Challenge of Guaranteeing Civil Liberties and Fundamental Freedoms 24 6. The Challenge of Ensuring Accountability 27 7. Conclusion 31 Appendix: Table 1: Results of Parliamentary Elections, February 1991 34 Table 2: Results of Parliamentary Elections, June 1996 34 Table 3: Results of Parliamentary Elections, October 2001 34 Figure 1: Rule of Law, 1996-2006 35 Figure 2: Political Stability and Absence of Violence, 1996-2006 35 Figure 3: Control of Corruption, 1996-2006 35 Figure 4: Voice and Accountability, 1996-2006 35 † This paper was prepared for the Institute of South Asian Studies, an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. ∗ Professor Rounaq Jahan is a Senior Research Scholar at the Southern Asian Institute, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University. She can be contacted at [email protected]. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bangladesh joined what Samuel P. Huntington had called the “third wave of democracy”1 after a people’s movement toppled 15 years of military rule in December 1990. In the next 15 years, the country made gradual progress in fulfilling the criteria of a “minimalist democracy”2 – regular free and contested elections, peaceful transfer of governmental powers as a result of elections, fundamental freedoms, and civilian control over policy and institutions. -

Who Did Not Registra

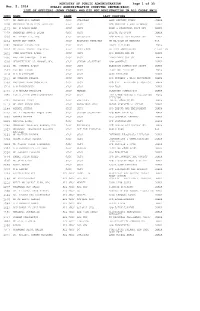

MINISTRY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Page 1 of 35 Mar. 2, 2016 PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION COMPUTER CENTRE(PACC) LIST OF OFFICERS (ADMN CADRE) WHO DID NOT REGISTRATION IN ALL CADRE PMIS IDNO NAME RANK LAST POSTING 1041 MD MAHFUZUR RAHMAN SECY CHAIRMAN LAND REFORMS BOARD DHAKA 1096 MOHAMMAD MOINUDDIN ABDULLAH SECY SECY M/O HOUSING & PUBLIC WORKS DHAKA 1171 DR. M ASLAM ALAM SECY SECY BANK & FINANCIAL INST DIV DHAKA 1229 KHANDKER ANWRUL ISLAM SECY SECY BRIDGE DIVISION DHAKA 1230 MD EBADOT ALI, NDC SECY OSD(SECY) M/O PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION DHAKA 1264 BARUN DEV MITRA SECY ECONOMIC MINISTER UN MISSION IN NEWYORK USA 1381 MONOWAR ISLAM, NDC SECY SECY POWER DIVISION DHAKA 1394 MD ABDUL MANNAN HOWLADER SECY HIGH COMM BD HIGH COMMISSION MAURITIUS 1431 SYED MONJURUL ISLAM SECY SECY M/O HEALTH AND FW DHAKA 1456 BHUIYAN SHAFIQUL ISLAM SECY SECY PRESIDENTS OFFICE DHAKA 1520 HEDAYETULLAH AL MAMOON, NDC SECY SENIOR SECRETARY M/O COMMERCE DHAKA 1521 MD. SIRAZUL ISLAM SECY SECY ELECTION COMMISSION SECTT DHAKA 1569 TARIQUL ISLAM SECY SECY PLANNING DIVISION DHAKA 1610 M A N SIDDIQUE SECY SECY ROAD DIVISION DHAKA 1653 MD HUMAYUN KHALID SECY SECY M/O PRIMARY & MASS EDUCATION DHAKA 1709 KHURSHED ALAM CHOWDHURY SECY SECY M/O CIVIL AVIATION & TOURISM DHAKA 1710 A M BADRUDDUJA SECY SECY M/O FOOD DHAKA 1733 S M GHULAM FAROOQUE SECY MEMBER PLANNING COMMISSION DHAKA 1876 FARID UDDIN AHMED CHOWDHURY SECY SECY IMPLE/MONITORING & EVALUATION DHAKA DIVISION 2007 MUSHFEKA IKFAT SECY CHAIRMAN TARIFF COMMISSION DHAKA 2113 MD ABUL KALAM AZAD SECY PRINCIPAL SECY PRIME MINISTER`S OFFICE DHAKA 2148 MIKAIL SHIPAR SECY SECY M/O LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT DHAKA 2232 DR. -

Icmab 17Th Council Election February 07, 2020

ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION FEBRUARY 07, 2020 CENTRAL VOTER LIST CENTRAL VOTER LIST ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION The Institute of Cost and Management Accountants of Bangladesh (ICMAB) ICMA Bhaban, Nilkhet, Dhaka-1205 CENTRAL VOTER LIST ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION FELLOW MEMBERS 1 F-0002 5 F-0030 Mr. Rafiq Ahmad FCMA Mr. A.B.M. Shamsuddin FCMA Executive Director Senior Financial Management Specialist T. K. Group of Industries Rural Transport Improvement Project-2 T.K. Bhaban (2nd floor) LGRD (World Bank Finance Project) 13, Kawran Bazar House # 289, Flat # A-3 Dhaka 1215 Road # 12, Block-A Bangladesh Bashundhara R/A Cell : 8801711566828 Dhaka E-mail : [email protected] Bangladesh Cell : 8801819252805 2 F-0016 E-mail : [email protected] Mr. Md. Afsarul Alam FCMA House No. 26 6 F-0032 Sonargaon Janapath (Chowrasta) Mr. D.P. Bhattacharyya FCMA Sector – 11 1403 Tropic Terrace Uttara Model Town FL 33903-5271 Dhaka 1230 United States of America (USA) Bangladesh Cell : 12396288687 Cell : 8801911216139 E-mail : [email protected] 3 F-0020 7 F-0034 Alhaj Md. Matior Rahman FCMA Mr. Md. Noor Baksh FCMA Makam-E-Mahmud, House # GA-117/2 House # 1, Road # 1, Block-B Middle Badda, Near Noor Moszid Palashpur, East Dania Gulshan, Dhaka 1212 Dhaka 1236 Bangladesh Bangladesh Cell : 8801778413531 Cell : 8801913805529 4 F-0027 8 F-0038 Mr. Md. Ishaque FCMA Mr. Muzaffar Ahmed FCMA Adviser President and CEO DBL Group Credit Rating Information and Services Ltd. Capita South Avenue (6th Floor) Nakshi Homes (4th floor) House # 50, Road # 3 6/1-A, Topkhana Road Gulshan Avenue Segunbagicha Gulshan- 1, Dhaka 1212 Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh Bangladesh Cell : 8801819213014 Cell : 8801713041913 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] Page 2 of 122 CENTRAL VOTER LIST ICMAB 17TH COUNCIL ELECTION 9 F-0042 15 F-0057 Mr. -

Convert JPG to PDF Online

Withheld list SL # Roll No 1 12954 2 00220 3 00984 4 05666 5 00220 6 12954 7 00984 8 05666 9 21943 10 06495 11 04720 1 SL# ROLL Name Father Marks 1 00002 MRINALINI DEY PARIJAT KUSUM PATWARY 45 2 00007 MD. MOHIUL ISLAM LATE. MD. NURUL ISLAM 43 3 00008 MD. SALAM KHAN RUHUL AMIN KHAN 40 4 00014 SYED AZAZUL HAQUE SAYED FAZLE HAQUE 40 5 00016 ROMANCE BAIDYA MILAN KANTI BAIDYA 51 6 00018 DIPAYAN CHOWDHURY SUBODH CHOWDHURY 40 7 00019 MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM MD. ABUL HASHEM 47 8 00021 MD. MASHUD-AL-KARIM SAHAB UDDIN 53 9 00023 MD. AZIZUL HOQUE ABDUL HAMID 45 10 00026 AHSANUL KARIM REZAUL KARIM 54 11 00038 MOHAMMAD ARFAT UDDIN MOHAMMAD RAMZU MIAH 65 12 00039 AYON BHATTACHARJEE AJIT BHATTACHARJEE 57 13 00051 MD. MARUF HOSSAIN MD. HEMAYET UDDIN 43 14 00061 HOSSAIN MUHAMMED ARAFAT MD. KHAIRUL ALAM 42 15 00064 MARJAHAN AKTER HARUN-OR-RASHED 45 16 00065 MD. KUDRAT-E-KHUDA MD. AKBOR ALI SARDER 55 17 00066 NURULLAH SIDDIKI BHUYAN MD. ULLAH BHUYAN 46 18 00069 ATIQUR RAHMAN OHIDUR RAHMAN 41 19 00070 MD. SHARIFUL ISLAM MD. ABDUR RAZZAQUE (LATE) 46 20 00072 MIZANUR RAHMAN JAHANGIR HOSSAIN 49 21 00074 MOHAMMAD ZIAUDDIN CHOWDHURY MOHAMMAD BELAL UDDIN CHOWDHURY 55 22 00078 PANNA KUMAR DEY SADHAN CHANDRA DEY 47 23 00082 WAYES QUADER FAZLUL QUDER 43 24 00084 MAHBUBUR RAHMAN MAZEDUR RAHMAN 40 25 00085 TANIA AKTER LATE. TAYEB ALI 51 26 00087 NARAYAN CHAKRABORTY BUPENDRA KUMER CHAKRABORTY 40 27 00088 MOHAMMAD MOSTUFA KAMAL SHAMSEER ALI 55 28 00090 MD. -

Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons

Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons (BCPS) 67, Shaheed Tajuddin Ahmed Ave, Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh Registered Applicant list, FCPS Part-I Examination-January-2021 BMDC NoName Speciality 27180 K.M. ABU MUSA- Anaesthesiology 29499 MD. SHAMIM KABIR SIDDQUE - Anaesthesiology 31090 MUHAMMAD MUNIRUZZAMAN - Anaesthesiology 33423 FATEMA KALI- Anaesthesiology 33697 MOHAMMED NAFEES ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 36857 MD. ASHRAFUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 38885 SYADA MAHZABIN TAHER- Anaesthesiology 39412 MOSHARRAF HOSSAIN - Anaesthesiology 40130 MOHAMMAD MIZAN UDDIN EMRAN- Anaesthesiology 40501 NORUN NAHAR- Anaesthesiology 42327 SOHANA SEKANDER- Anaesthesiology 43996 MOHAMMED MAMUN MORSHED- Anaesthesiology 44910 SYED MAHBOOB ISHTIAQUE AHMAD- Anaesthesiology 45105 ARUP RATAN BARAI - Anaesthesiology 46053 MD. ABU BAKER SIDDIQUE- Anaesthesiology 46101 TAHMINA BHUIYAN- Anaesthesiology 46632 SUHANA FERDOUS- Anaesthesiology 47119 MOHD.SAIF HOSSAIN JOARDER- Anaesthesiology 47129 RICHARD D' COSTA- Anaesthesiology 47565 MD. GIAS KAMAL CHOWDHURY MASUM- Anaesthesiology 48289 S. M. NAZRUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 48601 TAPASHI CHOWDHURY- Anaesthesiology 48825 JANNATH ARA FERDOUS- Anaesthesiology 50720 EVANA SAMAD- Anaesthesiology 51277 MD. KHIZIR HOSSAIN- Anaesthesiology 52570 SHAHANAJ SARMIN - Anaesthesiology 52891 TASNUVA TANZIL- Anaesthesiology 53159 AFIFA FERDOUS- Anaesthesiology 53350 SHOHELE SULTANA- Anaesthesiology 55285 MUNMUN BARUA- Anaesthesiology 55431 MOHAMMAD ZOHANUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 55459 ASHRAFUL ISLAM- Anaesthesiology 55588 MANSURA -

Progress of Higher Education in Colonial Bengal and After -A Case Study of Rajshahi Colle.Ge

PROGRESS OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN COLONIAL BENGAL AND AFTER -A CASE STUDY OF RAJSHAHI COLLE.GE. (1873-1973) Thesis Submitted to the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. ( ( l r"<t •· (•(.j 1:'\ !. By Md. Monzur Kadir Assistant Professor of Islamic History Rajshahi College, Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Under the Supervision of Dr. I. Sarkar Reader in History University of North Bengal,· Darjeeling, West Bengal, India. November, 2004. Ref. '?:J 1B. s-4 C124 oqa4 {(up I 3 DEC 2005 Md. Monzur Kadir, Assistant Professor, Research 5 cholar, Islamic History, Department of History Rajshahi College, Uni~ersity of North Bengal Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Darjeeling, India. DECLARATION . I hereby declare that the Thesis entitled "PROGRESS OF HIGHER EDUc;ATION IN COLONIAL BENGAL AND AFTER- A CASE STUDY OF RAJSHAHI COLLEGE (1873-1973)," submitted by me for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of the University of North Bengal, is a record of research work done by me and that the Thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship and similar other titles. II · 8 "' (Jl~Mt ~~;_ 10. -{ (Md. Monzur Kadir) Acknowledgement------------ This dissertation is the outcome of a doctoral research undertaken at the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India. It gives me immense pleasure to place on record the great help and co-operation. I received from several persons and institutions during the preparation of this dissertation. I am already obliged to Dr. I. Sarkar, Reader in History. North Bengal University who acted as my supervisor and for his urqualified support in its planning and execution. -

Icabnews Bulletinno

August 2011 ISSN 1993-5366 ICAB News BulletinNo. 262 Monthly News briefing from the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Bangladesh MEMBER OF: International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) Record Number of Candidates International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) pass final C A Exams South Asian Federation of Accountants (SAFA) The May-June 2011 ICAB Professional recently. Confederation of Asian and Examinations saw a record number of 84 The members of the Editorial Board Pacific Accountants (CAPA) candidates who have cleared their Final Exams congratulate the successful candidates and and are now eligible for membership of ICAB. wish them all success in their future IN THIS ISSUE Results of these examinations were published endeavours. Ë Record Number of Candidates pass final CA Exams Ë Candidates who have passed Professional Stage (Knowledge Level) Ë Candidates who have passed Application Level Md. Nahid Ullah Imtiaz Alam Sree Shimul Das Md Helal Uddin Ë President's Communication Ë Meeting with DFID Ë Meeting with MoC Ë Monthly Activities Ë IFAC News Ë Member's Status Mohammad Shahadat Ullah Mohammed Abul Kashem Md Johirul Islam Md Mosharof Hossain Ë Obituary Sk. Bellal Hossain Md. Golam Mostafa Mohammad Osman Goni Salim Ullah Bahadur ICAB News Bulletin No. 262 Gias Uddin Al Mamun Md. Nayeem Ibn Yousuf Md. Anwaruzzaman Esha Nabila Hussain Mohammad Afsar Uddin Mohammed Farhan Uddin Md. Hafizur Rahman Mohammad Golam Sarwar Mohammad Mokhlesur Rahman Salmaa Khan Mou Mohammad Touhidur Rahman Azizul Hassan Satter Muhammad Shajedul Hoque Tlukder Mohammad Ali Kawsar Md Anisur Rahaman Lingkon Mondal Kamal Hossain Ziaur Rahman Zia Md. Shariful Islam Moin Uddin Siddique Mohammad Saiful Islam Muhammad Kamruzzaman AHM Ariful Islam Muhammad Asaduzzaman Anupam Kumar Roy August 2011 2 ICAB News Bulletin No. -

The Challenges of Institutionalizing Democracy

ISAS Working Paper No. 39 – Date: 6 March 2008 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg The Challenges of Institutionalising † Democracy in Bangladesh Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University Contents Executive Summary i-iii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Challenges of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: A Global Discourse 4 3. The Challenge of Organising Free and Fair Elections 7 4. The Challenge of Establishing the Rule of Law 19 5. The Challenge of Guaranteeing Civil Liberties and Fundamental Freedoms 24 6. The Challenge of Ensuring Accountability 27 7. Conclusion 31 Appendix: Table 1: Results of Parliamentary Elections, February 1991 34 Table 2: Results of Parliamentary Elections, June 1996 34 Table 3: Results of Parliamentary Elections, October 2001 34 Figure 1: Rule of Law, 1996-2006 35 Figure 2: Political Stability and Absence of Violence, 1996-2006 35 Figure 3: Control of Corruption, 1996-2006 35 Figure 4: Voice and Accountability, 1996-2006 35 † This paper was prepared for the Institute of South Asian Studies, an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. ∗ Professor Rounaq Jahan is a Senior Research Scholar at the Southern Asian Institute, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University. She can be contacted at [email protected]. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bangladesh joined what Samuel P. Huntington had called the “third wave of democracy”1 after a people’s movement toppled 15 years of military rule in December 1990. In the next 15 years, the country made gradual progress in fulfilling the criteria of a “minimalist democracy”2 – regular free and contested elections, peaceful transfer of governmental powers as a result of elections, fundamental freedoms, and civilian control over policy and institutions. -

Directorate of Technical Education Recruitment Exam List of Eligible Candidates for the Final Exam (To Be Held on July 6, 2018 from 09:00 A.M

Directorate of Technical Education Recruitment Exam List of Eligible Candidates for the Final Exam (to be Held on July 6, 2018 from 09:00 A.M. to 10:00 A.M.) for the Post of Upper Division Assistant Sl. No. Roll No. Applicant's Name Father's Name 1 15000002 RAZIB AHMED MD. ABDUR RAZZAK 2 15000005 MD. ALAMGIR HOSSAIN MD. MAYNUL HAQUE 3 15000021 MD. KAMRUZZAMAN MD. SHEKH SADI 4 15000023 MD. IYUB ALI MD. SAHE ALAM 5 15000027 ABDUL AZAD ABDUR ROB 6 15000033 MD. ABUL KALAM AJAD MD. ABDUL AZIZ KHAN 7 15000036 RATHINDRA NATH PK. HARADHON CHANDRA PK. 8 15000038 MD. MOFAZZAL HOSSIN MD. AFSAR ALI 9 15000040 MD. EMRUL HASAN MD. ABDUR RASHID MIAH 10 15000058 SUBRTA RUDRA PAUL SAJAL RUDRA PAUL 11 15000059 MD. MIRAJUL HASSIN TAUFIQUE MD. HABIBUR RAHMAN SARKER 12 15000067 MD. SAIFUR RAHAMAN MD. DABIRUL ISLAM 13 15000068 SARMIN AFROZ SUMI MD. SEKENDER ALI 14 15000069 MOHAMMAD OMAR FARUQ MOHAMMAD ABDUL KARIM 15 15000081 MD. MASUD RANA MD. ABDUL MATIN 16 15000082 HASAN HASIBUR RAHMAN RISHAT MD. MEHERUN NESA 17 15000091 MD. ABU TAREQ MD. ABU BAKAR SIDDIQUE 18 15000108 SAKILA YASMIN ABDUL GOFUR MOLLAH 19 15000110 TARAK AHMMD SHIMUL MD. ABDUL GAFUR 20 15000111 MD. IBRAHIM KHALIL MD.SALAMAT MOLLAH 21 15000122 JAMUNA ROY JANU RAM ROY 22 15000123 MD. ABDUL HAQUE AHSAN ALI 23 15000126 SAMAPTI BISWAS GAURANGA LAL BISWAS 24 15000128 JAKAIA SULTANA MD. ABDUR RAZZAQUE 25 15000135 HARIDAS CHANDRA DAS SACHINDRA CHANDRA DAS 26 15000147 SAJAL KUMAR MANDAL ZATINDRA NATH MANDAL 27 15000148 JESMIN AHMED JOKIM UDDIN AHMED 28 15000150 SIMA MD.ABDUL KADER 29 15000151 MD.MAIDUL ISLAM LATE.NASER UDDIN AHMED 30 15000152 SUBRATA PANUA PRAMANANDA PANUA 31 15000156 MD. -

ISLAMIC EDUCATION in BANGLADESH Tradition, Trends, and Trajectories

ISLAMIC EDUCATION IN BANGLADESH Tradition, Trends, and Trajectories Mumtaz Ahmad Professor of Political Science Hampton University, Hampton, VA 23668 <[email protected]> Paper prepared for the Islamic Education in South & Southeast Asia Survey Project of the National Bureau of Asian Research, June 2006. Preliminary draft; not to be quoted/ published in any form without the author’s consent. Mumtaz Ahmad is professor in Hampton University’s Department of Political Science. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ “Fundamentalism Project,” Dr. Ahmad has been a Research Fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Fellow of the American Institute of Pakistan Studies and the International Institute of Islamic Thought, a Fulbright Professor in Bangladesh and Pakistan, and a Visiting Professor at International Islamic University, Kuala Lumpur. Dr. Ahmad holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Chicago. His main areas of academic interest are the comparative politics of South Asia and the Middle East, Islamic political thought and institutions, and the comparative politics of contemporary Islamic revivalism. Dr. Ahmad has published seven books and numerous papers and articles on politics of Islamic resurgence and Islamic developments in South Asia and the Middle East. CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY: NO REDISTRIBUTION WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF ASIAN RESEARCH Islamic Education in Bangladesh ORGANIZATION OF THE PAPER Executive Summary ...........................................................................................................44 -

VOTER LIST Voter List ICMAB Dhaka Branch Council Election VOTER LIST ICMAB DHAKA BRANCH COUNCIL ELECTION for the TERM 2020 & 2021 FELLOW MEMBERS

ICMAB DHAKA BRANCH COUNCIL ELECTION (FOR THE TERM 2020 & 2021) FEBRUARY 07, 2020 VOTER LIST Voter List ICMAB Dhaka Branch Council Election VOTER LIST ICMAB DHAKA BRANCH COUNCIL ELECTION FOR THE TERM 2020 & 2021 FELLOW MEMBERS 1 F-0002 7 F-0027 Mr. Rafiq Ahmad FCMA Mr. Md. Ishaque FCMA Executive Director Adviser T. K. Group of Industries DBL Group T.K. Bhaban (2nd floor) Capita South Avenue (6th Floor) 13, Kawran Bazar House # 50, Road # 3 Dhaka 1215, Bangladesh Gulshan Avenue, Gulshan- 1 Cell : 8801711566828 Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh E-mail : [email protected] Cell : 8801713041913 E-mail : [email protected] 2 F-0003 Prof. Aminul Islam FCMA 8 F-0029 House # 07, Road # 12 Mr. Mohammad Golam Mostafa FCMA Kalyanpur, Mirpur House # 25, Road # 10 Dhaka 1216, Bangladesh Sector # 10, Uttara Cell : 8801741495726 Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh Cell : 8801731469333 3 F-0005 Mr. Md. Uttam Ali Miah FCMA 9 F-0030 Past President, ICMAB Mr. A.B.M. Shamsuddin FCMA Building # 17, Flat # 1502 Senior Financial Management Specialist Japan Garden City, Tajmahal Road Rural Transport Improvement Project-2 Mohammadpur LGRD (World Bank Finance Project) Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh House # 289, Flat # A-3, Road # 12 Cell : 8801317269208 Block-A, Bashundhara R/A Dhaka, Bangladesh Cell : 8801819252805 4 F-0016 E-mail : [email protected] Mr. Md. Afsarul Alam FCMA House No. 26 10 F-0033 Sonargaon Janapath (Chowrasta) Mr. Pritimoy Paul Chowdhury FCMA Sector - 11, Uttara Model Town 295/A/1, Monowara Sikdar Apartment Dhaka 1230, Bangladesh Tally Office Road, Rayer Bazar, Building # 02 Cell : 8801911216139 Flat # 02 (1st Floor) Dhaka 1209, Bangladesh 5 F-0020 Cell : 8801719380333 Alhaj Md.