Use of (R)-Phenylpiracetam for the Treatment of Sleep Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nootropics: Boost Body and Brain? Report #2445

NOOTROPICS: BOOST BODY AND BRAIN? REPORT #2445 BACKGROUND: Nootropics were first discovered in 1960s, and were used to help people with motion sickness and then later were tested for memory enhancement. In 1971, the nootropic drug piracetam was studied to help improve memory. Romanian doctor Corneliu Giurgea was the one to coin the term for this drug: nootropics. His idea after testing piracetam was to use a Greek combination of “nous” meaning mind and “trepein” meaning to bend. Therefore the meaning is literally to bend the mind. Since then, studies on this drug have been done all around the world. One test in particular studied neuroprotective benefits with Alzheimer’s patients. More tests were done with analogues of piracetam and were equally upbeat. This is a small fraction of nootropic drugs studied over the past decade. Studies were done first on animals and rats and later after results from toxicity reports, on willing humans. (Source: https://www.purenootropics.net/general-nootropics/history-of-nootropics/) A COGNITIVE EDGE: Many decades of tests have convinced some people of how important the drugs can be for people who want an enhancement in life. These neuro-enhancing drugs are being used more and more in the modern world. Nootropics come in many forms and the main one is caffeine. Caffeine reduces physical fatigue by stimulating the body’s metabolism. The molecules can pass through the blood brain barrier to affect the neurotransmitters that play a role in inhibition. These molecule messengers can produce muscle relaxation, stress reduction, and onset of sleep. Caffeine is great for short–term focus and alertness, but piracetam is shown to work for long-term memory. -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

UFC PROHIBITED LIST Effective June 1, 2021 the UFC PROHIBITED LIST

UFC PROHIBITED LIST Effective June 1, 2021 THE UFC PROHIBITED LIST UFC PROHIBITED LIST Effective June 1, 2021 PART 1. Except as provided otherwise in PART 2 below, the UFC Prohibited List shall incorporate the most current Prohibited List published by WADA, as well as any WADA Technical Documents establishing decision limits or reporting levels, and, unless otherwise modified by the UFC Prohibited List or the UFC Anti-Doping Policy, Prohibited Substances, Prohibited Methods, Specified or Non-Specified Substances and Specified or Non-Specified Methods shall be as identified as such on the WADA Prohibited List or WADA Technical Documents. PART 2. Notwithstanding the WADA Prohibited List and any otherwise applicable WADA Technical Documents, the following modifications shall be in full force and effect: 1. Decision Concentration Levels. Adverse Analytical Findings reported at a concentration below the following Decision Concentration Levels shall be managed by USADA as Atypical Findings. • Cannabinoids: natural or synthetic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or Cannabimimetics (e.g., “Spice,” JWH-018, JWH-073, HU-210): any level • Clomiphene: 0.1 ng/mL1 • Dehydrochloromethyltestosterone (DHCMT) long-term metabolite (M3): 0.1 ng/mL • Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs): 0.1 ng/mL2 • GW-1516 (GW-501516) metabolites: 0.1 ng/mL • Epitrenbolone (Trenbolone metabolite): 0.2 ng/mL 2. SARMs/GW-1516: Adverse Analytical Findings reported at a concentration at or above the applicable Decision Concentration Level but under 1 ng/mL shall be managed by USADA as Specified Substances. 3. Higenamine: Higenamine shall be a Prohibited Substance under the UFC Anti-Doping Policy only In-Competition (and not Out-of- Competition). -

Gsk3β: a Master Player in Depressive Disorder Pathogenesis and Treatment Responsiveness

cells Review GSK3β: A Master Player in Depressive Disorder Pathogenesis and Treatment Responsiveness Przemysław Duda * , Daria Hajka , Olga Wójcicka , Dariusz Rakus and Agnieszka Gizak * Department of Molecular Physiology and Neurobiology, University of Wrocław, Sienkiewicza 21, 50-335 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] (D.H.); [email protected] (O.W.); [email protected] (D.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.D.); [email protected] (A.G.); Tel.: +48713754135 (A.G.) Received: 4 February 2020; Accepted: 14 March 2020; Published: 16 March 2020 Abstract: Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), originally described as a negative regulator of glycogen synthesis, is a molecular hub linking numerous signaling pathways in a cell. Specific GSK3β inhibitors have anti-depressant effects and reduce depressive-like behavior in animal models of depression. Therefore, GSK3β is suggested to be engaged in the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder, and to be a target and/or modifier of anti-depressants’ action. In this review, we discuss abnormalities in the activity of GSK3β and its upstream regulators in different brain regions during depressive episodes. Additionally, putative role(s) of GSK3β in the pathogenesis of depression and the influence of anti-depressants on GSK3β activity are discussed. Keywords: GSK3β; MDD; depression; anti-depressants; AKT; BDNF; neuroprotection 1. Introduction 1.1. Major Depressive Disorder According to the World Health Organization’s statistics for March 2018, depression is a major contributor to the overall global burden of diseases. Globally, more than 300 million people suffer from depression. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS-5), major depressive disorder (MDD), the principal form of depression, is characterized by the following key symptoms: depressed mood and anhedonia (which are the fundamental symptoms), suicidal ideation, plan or attempt, fatigue, sleep deprivation, loss of weight and appetite, and psychomotor retardation [1]. -

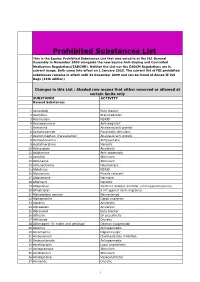

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Summer 2017 P

In this Issue: • Toxicology Results Timelines Explained • Collection of Blood and Urine Samples for Tox Testing • New Opioid Drugs Implicated in Oregon Deaths • A New Tox Instrument Promises Improved Analysis • Tox Top 24: 2016 vs. 2011 SUMMER 2017 P a g OREGON STATE POLICE e Forensic Services Division Newsletter | TOXICOLOGY TOPICS STILL WAITING FOR THOSE TOX RESULTS? WHY DOES IT TAKE SO LONG? By Jeff Eitner, Springfield Lab The answer is more complicated than you may imagine. We know it can be frustrating to wait six months or longer for the results of a urine analysis. This timeline is a reflection of our backlog rather than the time required for analysis. Toxicology analysis takes place in the Portland Metro and Springfield Forensic Labs, and it typically requires two weeks or less to do the analysis and issue a report. The long waiting times are a function of a large backlog of old cases that has been created by chronic understaffing. A common misconception is that our analysis is equivalent to workplace drug testing, which only gives results on the potential presence of certain common drug classes, such as amphetamines, opiates, or benzodiazepines. Those results do not distinguish between controlled and non-controlled substances—a necessary part of DUII litigation. Our analysis specifically identifies the individual drugs present in a urine sample. For a toxicologist, the majority of the analytical time is spent reviewing large quantities of instrumental data. Each sample is first screened for general drug classes, and then analyzed on our gas chromatograph/ mass spectrometers (GC/MS) at least once. -

World of Cognitive Enhancers

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 11 September 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.546796 The Psychonauts’ World of Cognitive Enhancers Flavia Napoletano 1,2, Fabrizio Schifano 2*, John Martin Corkery 2, Amira Guirguis 2,3, Davide Arillotta 2,4, Caroline Zangani 2,5 and Alessandro Vento 6,7,8 1 Department of Mental Health, Homerton University Hospital, East London Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 2 Psychopharmacology, Drug Misuse, and Novel Psychoactive Substances Research Unit, School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom, 3 Swansea University Medical School, Institute of Life Sciences 2, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom, 4 Psychiatry Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Catania, Catania, Italy, 5 Department of Health Sciences, University of Milan, Milan, Italy, 6 Department of Mental Health, Addictions’ Observatory (ODDPSS), Rome, Italy, 7 Department of Mental Health, Guglielmo Marconi” University, Rome, Italy, 8 Department of Mental Health, ASL Roma 2, Rome, Italy Background: There is growing availability of novel psychoactive substances (NPS), including cognitive enhancers (CEs) which can be used in the treatment of certain mental health disorders. While treating cognitive deficit symptoms in neuropsychiatric or neurodegenerative disorders using CEs might have significant benefits for patients, the increasing recreational use of these substances by healthy individuals raises many clinical, medico-legal, and ethical issues. Moreover, it has become very challenging for clinicians to Edited by: keep up-to-date with CEs currently available as comprehensive official lists do not exist. Simona Pichini, Methods: Using a web crawler (NPSfinder®), the present study aimed at assessing National Institute of Health (ISS), Italy Reviewed by: psychonaut fora/platforms to better understand the online situation regarding CEs. -

Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, Vol

Research Archive Citation for published version: Barbara Loi, Mire Zloh, Maria Antonietta De Luca, Nicholas Pintori, John Corkery, and Fabrizio Schifano, ‘4,4′- Dimethylaminorex (“4,4′-DMAR”; “Serotoni”) misuse: A Web- based study, Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, Vol. 32 (3):e2575, May 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2575 Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Users should always cite the published version of record. Copyright and Reuse: This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact the Research & Scholarly Communications Team at [email protected] Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 4,4’ -dimethylaminorex ('4,4’ -DMAR’; ‘Serotoni’) misuse; a web-based study Journal:For Human Peer Psychopharmacology: Review Clinical and Experimental Manuscript ID HUP-16-0111.R1 Wiley - Manuscript type: Special issue on novel psychoactive substances Date Submitted by the Author: 21-Jan-2017 Complete List of Authors: Loi, Barbara; University of Hertfordshire School of Life and Medical Sciences, Department of Pharmacy, Postgraduate Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Hertfordshire, UK Zloh, Mire; University of Hertfordshire School of Life and Medical Sciences, Psychopharmacology, Drug Misuse and Novel Psychoactive Substances Research Unit, -

Article Published In: Neuroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of DAT Inhibitor

Article published in: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-020-00705-7 Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activity of DAT inhibitor R-phenylpiracetam in experimental models of inflammation in male mice Liga Zvejniece1,*, Baiba Zvejniece1, 2, Melita Videja1, 3, Gundega Stelfa1, 4, Edijs Vavers1, Solveiga Grinberga1, Baiba Svalbe1 and Maija Dambrova1, 3 1Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis, Riga, Latvia, 2Latvian University Faculty of Medicine, Riga, Latvia, 3Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia, 4Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies, Jelgava, Latvia *Correspondence to: L Zvejniece, Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis, 21 Aizkraukles Street, Riga, LV-1006, Latvia. E-mail: [email protected] Running title R-phenylpiracetam possesses anti-inflammatory activity Keywords Inflammation; R-phenylpiracetam; LPS-induced endotoxaemia model; Carrageenan-induced paw oedema; Formalin-induced paw licking test Acknowledgments This work was in part founded by the Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis internal grant. We thank JSC Olainfarm for providing target profiling data for R-phenylpiracetam. Abbreviations R-PhP - R-phenylpiracetam (R-PhP, (4R)-2-(4-phenyl-2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide) DAT - Dopamine transporter LPS – lipopolysaccharide I.p. - intraperitoneal P.o. - peroral TNF-α - tumour necrosis factor-α IL-1β - interleukin 1 beta iNOS - inducible nitric oxide synthase DA - dopamine S-PhP - S-phenylpiracetam UPLC⁄MS⁄MS - ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry PCR - polymerase chain reaction SEM - standard error of the mean ANOVA - analysis of variance Article published in: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-020-00705-7 Abstract R-phenylpiracetam (R-PhP, (4R)-2-(4-phenyl-2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide) is an optical isomer of phenotropil, a clinically used nootropic drug that improves the physical condition and cognition. -

Carphedon at the Crossroads: a Dangerous Drug Or a Promising Psychopharmaceutical?

Global Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences ISSN: 2573-2250 Review Article Glob J Pharmaceu Sci Volume 7 Issue 2 - June 2019 DOI: 10.19080/GJPPS.2019.07.555713 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Jiri Patocka Carphedon at the Crossroads: A Dangerous Drug or a Promising Psychopharmaceutical? Jiri Patocka1,2* 1Faculty of Health and Social Studies, University of South Bohemia České Budějovice, Czech Republic 2Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospital, Czech Republic Submission: March 18, 2019; Published: June 04, 2019 *Corresponding author: Jiri Patocka, University of South Bohemia České Budějovice, Faculty of Health and Social Studies, Institute of Radiology, Toxicology and Civil Protection, České Budějovice, Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospital, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic Abstract Carphedon is a phenyl derivative of the nootropic drug piracetam (Nootropil) and is effective in increasing physical endurance and cold resistance and is used for amnesia treatment. It was developed in Russia as a stimulant to keep astronauts awake on long missions, and occasionally used in Russia as a nootropic prescription for various types of neurological disease. It became well known a couple years ago when a leading nootropic supplier in California started selling it on the Internet as a supplement and a bunch of athletes got kicked out of the Olympics for illegal using it. Carphedon was found to activate the operant behavior more powerfully, to remove psychodepressant effects of diazepam, to inhibit post-rotational nystagmus, and to prevent the development of retrograde amnesia. Unlike piracetam, carphedon exhibits a specific anticonvulsant action. When given in high doses, produces psychodepressant effects. It is also claimed to increase physical stamina and provide improvedKeywords: tolerance to cold. -

Pharmacology of Stimulants Prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)

British Journal of Pharmacology (2008) 154, 606–622 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0007– 1188/08 $30.00 www.brjpharmacol.org REVIEW Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) JR Docherty Department of Physiology, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland This review examines the pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Stimulants that increase alertness/reduce fatigue or activate the cardiovascular system can include drugs like ephedrine available in many over- the-counter medicines. Others such as amphetamines, cocaine and hallucinogenic drugs, available on prescription or illegally, can modify mood. A total of 62 stimulants (61 chemical entities) are listed in the WADA List, prohibited in competition. Athletes may have stimulants in their body for one of three main reasons: inadvertent consumption in a propriety medicine; deliberate consumption for misuse as a recreational drug and deliberate consumption to enhance performance. The majority of stimulants on the list act on the monoaminergic systems: adrenergic (sympathetic, transmitter noradrenaline), dopaminergic (transmitter dopamine) and serotonergic (transmitter serotonin, 5-HT). Sympathomimetic describes agents, which mimic sympathetic responses, and dopaminomimetic and serotoninomimetic can be used to describe actions on the dopamine and serotonin systems. However, many agents act to mimic more than one of these monoamines, so that a collective term of monoaminomimetic may be useful. Monoaminomimietic actions of stimulants can include blockade of re-uptake of neurotransmitter, indirect release of neurotransmitter, direct activation of monoaminergic receptors. Many of the stimulants are amphetamines or amphetamine derivatives, including agents with abuse potential as recreational drugs. -

Neurochemical and Neuropharmacological Studies on a Range Of

Neurochemical and Neuropharmacological Studies on a Range of Novel Psychoactive Substances by Barbara Loi Dissertation Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Psychopharmacology, Drug Misuse and Novel Psychoactive Substances Research Unit Hertfordshire, UK School of Life and Medical Sciences University of Hertfordshire Date: November 2017 1 Table of contents Table of contents ..................................................................................................................................... 2 List of figures .......................................................................................................................................... 6 List of tables .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Aknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 11 List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. 12 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. 14 Aims, objectives and hypotheses of the overall PhD project ................................................................ 17 Chapter 1: Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPS) ..............................................................................