Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suspected Or Convicted Serial Killers in Washington 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 John R

Suspected or convicted serial killers in Washington 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 John R. Gasser Harvy L. Carignan James Dwight Canady What is a serial killer? Even the nation’s leading experts don’t agree. The most general Warren Forrest definition is based on numbers and patterns: Two or more unrelated victims in distinctly Gary G. Grant Ted Bundy separate incidents. The Northwest has a notorious history of these “prototype” The .22 Caliber Killer, killers – among them are Ted Bundy and the Green River Killer, who Identity unknown, James Elledge Brian Keith Lord are synonymous with the term “serial killer.” Spokane The same killer is believed James Edward Ruzicka Yet other, less infamous killers have claimed scores of lives across the state. to be responsible for three Gary A. Taylor Some have been convicted of only one or two murders, but are suspected slayings of women found William Batten of many more. Four remain only suspects, pending trial. dumped near the Spokane Robert Lee Yates Jr. River in 1990. All of the victims Kenneth Bianchi were known prostitutes shot with the s Following general definitions provided by the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, criminal Morris Frampton profilers and other experts, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer compiled this list of the state’s ame .22 caliber gun. Investigators once looked at the crimes in relation to a string of Stanley Bernson modern-day serial killers. prostitute killings in Spokane that Robert Lee Lewiston Valley Killer It’s impossible to know if the list is comprehensive. -

A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing: Decoding the Language of a Psychopath BY

A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: Decoding the Language of a Psychopath BY KERRI ANDERSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Forensic Psychology California Baptist University School of Behavioral Sciences 2017 ii SCHOOL OF BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES The thesis of Kerri Anderson, approved by her Committee, has been accepted and approved by the Faculty of the School of Behavioral Sciences, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Forensic Psychology. Thesis Committee: _____________________________ [Name, Title] _____________________________ [Name, Title] _____________________________ [Name, Title] Committee Chairperson [Date] iii DEDICATION It is so common to be traditional and dedicate a work of science to one’s parents, spouses, children, friends, and mentors. As if one felt the need to give back for what has been taken. But a contribution to science, and I have desperately tried here to make a contribution to science, always includes a vast amount of taking from previous researchers, professors, and scholars. Then adding a little bit according to one’s ability and then giving back not to one’s scholars and colleagues but to the whole community and to other people as well, who might find the work interesting and resourceful, and bring it on. It is for those individuals that this work has been written and to them that it is dedicated so, here is my Forensic Psychology Master’s Thesis to whoever finds it interesting and a viable contribution to uncovering the root causes of psychopathy. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. -

Fiscal Note Package 34902

Multiple Agency Fiscal Note Summary Bill Number: 1504 HB Title: Eliminating death penalty Estimated Cash Receipts Agency Name 2013-15 2015-17 2017-19 GF- State Total GF- State Total GF- State Total Office of Attorney General Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion." Total $ 0 0 0 0 0 0 Estimated Expenditures Agency Name 2013-15 2015-17 2017-19 FTEs GF-State Total FTEs GF-State Total FTEs GF-State Total Administrative Office Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. of the Courts Office of Public Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. Defense Office of Attorney Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. General Caseload Forecast .0 0 0 .0 0 0 .0 0 0 Council Department of Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. Corrections Total 0.0 $0 $0 0.0 $0 $0 0.0 $0 $0 Local Gov. Courts * Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion. Local Gov. Other ** (3,900,000) (3,900,000) (3,900,000) Local Gov. Total (3,900,000) (3,900,000) (3,900,000) Estimated Capital Budget Impact NONE Prepared by: Kate Davis, OFM Phone: Date Published: (360) 902-0570 Final 3/ 5/2013 * See Office of the Administrator for the Courts judicial fiscal note ** See local government fiscal note FNPID 34902 : FNS029 Multi Agency rollup Judicial Impact Fiscal Note Bill Number: 1504 HB Title: Eliminating death penalty Agency: 055-Admin Office of the Courts Part I: Estimates No Fiscal Impact Estimated Cash Receipts to: Account FY 2014 FY 2015 2013-15 2015-17 2017-19 Counties Cities Total $ Estimated Expenditures from: Non-zero but indeterminate cost. -

The Metaphysics of the Hangman

Chapter 4 The Metaphysics of the Hangman Prior to introduction of the electric chair in 1890, hanging was the prin- cipal and, more often than not, the exclusive method of state-sponsored killing in all of the United States (Drimmer 1990). Indeed, of the nearly twenty thousand documented executions conducted since the found- ing of the first permanent English settlement at Jamestown, close to two-thirds have been accomplished by this means (Macdonald 1993). Today, however, this practice stands poised at the brink of extinction. Eliminated by Congress for civilians convicted of federal crimes in 1937 and by the army in 1986, hanging is still prescribed in only four states.1 The members of this quartet have performed a total of three hangings since its revival, following a twenty-eight year hiatus, in 1993. Yet even these states now prescribe lethal injection as their default method of execution; and, in all likelihood, they will retain hanging as an option only so long as it is necessary to foreclose legal challenges by persons sentenced under earlier statutes. In short, the noose is quickly passing into obsolescence and so, like the rack and the gibbet, is destined to van- ish—except perhaps as a curiosity of historical inquiry and museum exhibition. What are we to make of the virtual demise of state-sponsored hangings? To offer a partial response to this question, in this chapter, I explore a neglected dimension of what is arguably the most sustained judicial inquiry into hanging ever conducted in the United States. In February 1994, a bitterly divided eleven-member panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Charles Campbell’s challenge to hanging’s constitutionality (Campbell v. -

Chapter 6: Sex Crime ❖ 193

06-Helfgott-45520.qxd 2/12/2008 6:23 PM Page 191 6 ❖ Sex Crime Surely if humans, far and wide, wound the genitals, we hate them; we hate where they take us, what we do with them. —Andrea Dworkin (1987, p. 194) In March 2001, Armin Meiwes, a 42-year-old computer expert, murdered 43-year-old Bernd Juergen Brandes, a microchip engineer, in his home in Rotenburg, Germany. The two met after Brandes answered an Internet advertisement placed by Meiwes for a young man interested in “slaughter and consumption.” Meiwes testified in court that the killing began after the two engaged in sadomasochistic sex acts when, at Brandes’s request, he tried unsuccessfully to bite off Brandes’s penis, and then cut it off with a knife. The two then tried to eat the penis raw, then fried it in a pan trying unsuccessfully to eat it. Brandes eventually went unconscious from loss of blood after lying for hours in the bath- tub while Meiwes read magazines and drank wine. Meiwes then hung Brandes from a butcher’s hook and slaughtered him. The slaughter included severing his head, disem- bowelment, laying him out on a butcher block, and chopping his body into pieces. After the killing, Meiwes froze portions of the body, kept the skull in the freezer, buried other body parts in the garden, and ate 44 pounds of the body over the months to follow. Meiwes videotaped the entire event, watched it later to become sexually aroused, and spoke in court about how watching horror films as a child fueled his fantasies and long- time desires to commit such acts (“German Cannibal Tells of Fantasy,” December 3, 2003). -

Neurodevelopmental and Psychosocial Risk Factors in Serial Killers and Mass Murderers

Allely, Clare S., Minnis, Helen, Thompson, Lucy, Wilson, Philip, and Gillberg, Christopher (2014) Neurodevelopmental and psychosocial risk factors in serial killers and mass murderers. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19 (3). pp. 288-301. ISSN 1359-1789 Copyright © 2014 The Authors http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/93426/ Deposited on: 23 June 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Aggression and Violent Behavior 19 (2014) 288–301 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aggression and Violent Behavior Neurodevelopmental and psychosocial risk factors in serial killers and mass murderers Clare S. Allely a, Helen Minnis a,⁎,LucyThompsona, Philip Wilson b, Christopher Gillberg c a Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, RHSC Yorkhill, Glasgow G3 8SJ, Scotland, United Kingdom b Centre for Rural Health, University of Aberdeen, The Centre for Health Science, Old Perth Road, Inverness IV2 3JH, Scotland, United Kingdom c Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden article info abstract Article history: Multiple and serial murders are rare events that have a very profound societal impact. We have conducted a Received 11 July 2013 systematic review, following PRISMA guidelines, of both the peer reviewed literature and of journalistic and Received in revised form 20 February 2014 legal sources regarding mass and serial killings. Our findings tentatively indicate that these extreme forms of vi- Accepted 8 April 2014 olence may be a result of a highly complex interaction of biological, psychological and sociological factors and Available online 18 April 2014 that, potentially, a significant proportion of mass or serial killers may have had neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder or head injury. -

Geographic Profiling : Target Patterns of Serial Murderers

GEOGRAPHIC PROFILING: TARGET PATTERNS OF SERIAL MURDERERS Darcy Kim Rossmo M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1987 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the School of Criminology O Darcy Kim Rossmo 1995 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY October 1995 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Darcy Kim Rossmo Degree: ' Doctor of Philosophy Title of Dissertation: Geographic Profiling: Target Patterns of Serial Murderers Examining Committee: Chair: Joan Brockrnan, LL.M. d'T , (C I - Paul J. ~>ahtin~harp~~.,Dip. Crim. Senior Supervisor Professor,, School of Criminology \ I John ~ow&an,PhD Professor, School of Criminology John C. Yuille, PhD Professor, Department of Psychology Universim ofJritish Columbia I I / u " ~odcalvert,PhD, P.Eng. Internal External Examiner Professor, Department of Computing Science #onald V. Clarke, PhD External Examiner Dean, School of Criminal Justice Rutgers University Date Approved: O&Zb& I 3, 1 9 9.5' PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser Universi the right to lend my thesis, pro'ect or extended essay (the title o? which is shown below) to users otJ the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

Fiscal Note Package 31143

Multiple Agency Fiscal Note Summary Bill Number: 6283 SB Title: Death penalty elimination Estimated Cash Receipts Agency Name 2011-13 2013-15 2015-17 GF- State Total GF- State Total GF- State Total Office of Attorney General Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion." Total $ 0 0 0 0 0 0 Estimated Expenditures Agency Name 2011-13 2013-15 2015-17 FTEs GF-State Total FTEs GF-State Total FTEs GF-State Total Administrative Office Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. of the Courts Office of Public Fiscal note not available Defense Office of Attorney Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. General Caseload Forecast .0 0 0 .0 0 0 .0 0 0 Council Department of Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. Corrections Total 0.0 $0 $0 0.0 $0 $0 0.0 $0 $0 Local Gov. Courts * Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion. Local Gov. Other ** Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion. Local Gov. Total Estimated Capital Budget Impact NONE Prepared by: Adam Aaseby, OFM Phone: Date Published: 360-902-0539 Final 1/27/2012 * See Office of the Administrator for the Courts judicial fiscal note ** See local government fiscal note FNPID 31143 : FNS029 Multi Agency rollup Judicial Impact Fiscal Note Bill Number: 6283 SB Title: Death penalty elimination Agency: 055-Admin Office of the Courts Part I: Estimates No Fiscal Impact Estimated Cash Receipts to: Account FY 2012 FY 2013 2011-13 2013-15 2015-17 Counties Cities Total $ Estimated Expenditures from: Non-zero but indeterminate cost. -

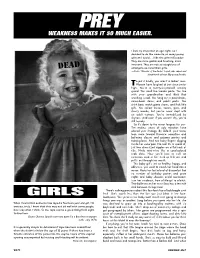

Weakness Makes It So Much Easier

PREY WEAKNESS MAKES IT SO MUCH EASIER. I lost my innocence at age eight, so I decided to do the same to as many young girls as I could.…I like the girls in Ecuador. They are more gentle and trusting, more innocent. They are not as suspicious of DEAD strangers as Colombian girls. —Pedro “Monster of the Andes” Lopez, who raped and slaughtered at least fifty young females o put it kindly, you aren’t a ladies’ man. T Women have laughed at you since junior high. You’re a twenty-six-year-old security guard. You smell like tomato paste. You live with your grandmother and think that wrestling is real. You hang out in pawnshops, comic-book stores, and public parks. You drink beer, watch game shows, and fuck little girls. You collect knives, razors, guns, and cherry bombs, but you’ve never slept with an adult woman. You’re immobilized by shyness. And even if you weren’t shy, you’re still homely. So it’s down to the minor leagues for you. The endless years of ugly rejection have altered your strategy. By default, your tastes lean more toward Brownie campfires and ballerina classes and pajama parties and training bras. And two hairy fingers digging inside her swee’pea. No real tits to speak of, just two dime-sized nipples on a flat rack o’ ribs. Nude mini-vulva like a coral-colored crab claw. How you’d love to stuff an extension cord in her stuck-up little ass and pull it out through her mouth. -

Is Electrocution an Unconstitutional Method of Execution? the Engineering of Death Over the Century

William & Mary Law Review Volume 35 (1993-1994) Issue 2 Article 4 February 1994 Is Electrocution an Unconstitutional Method of Execution? The Engineering of Death over the Century Deborah W. Denno Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Deborah W. Denno, Is Electrocution an Unconstitutional Method of Execution? The Engineering of Death over the Century, 35 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 551 (1994), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmlr/vol35/iss2/4 Copyright c 1994 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr IS ELECTROCUTION AN UNCONSTITUTIONAL METHOD OF EXECUTION? THE ENGINEERING OF DEATH OVER THE CENTURY DEBORAH W. DENNO* INTRODUCTION ......................................... 554 I. KEMMLER 'S HISTORICAL FOUNDATIONS ............... 559 A. The Eighth Amendment's Concept of "Cruel and Unusual".... ........................... 560 B. New York's Anti-CapitalPunishment Movement 562 C. The Electrocution Act and the "Battle of the Currents".................................... 566 1. The AC-DC Controversy ................. 568 2. The Commission Recommends Electricity. 573 II. THE CREDIBILITY AND CONSEQUENCES OF KEMMLER 'S INTERPRETATION OF "CRUEL AND UNUSUAL" ............ 577 A. Kemmler I: Death by Electrocution ........... 577 B. Kemmler II: Electrocution and "The Scientific Progress of the Age" ........................ 578 1. The Evidentiary Hearings ............... 579 * Associate Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law. B.A., 1974, University of Virginia; M.A., 1975, University of Toronto; Ph.D., 1982, J.D., 1989, University of Penn- sylvania. I am most grateful to the following individuals for their comments on this Article: Vivian Berger, Leigh Bienen, James Fleming, Robert Kaczorowski, James Kainen, Maria Marcus, Michael Martin, Joseph Perillo, Michael Radelet, and Steven Walt. -

Update from a Would Be Criminal Mastermind

Kevin Crosby 30 June 1997 Update From A Would-Be Criminal Mastermind If we want to solve the problems with our youth such as drugs, illicit sex, crime, vandalism, gangs and even the terribly high rate of teen suicide we must stop dealing with the symptoms and look at the disease. 1 For too many of our youth life has no meaning. They are screaming at us to give them some moorings and purpose in life. 2 “Kids know them as “roofies.” ” ________________________________________________6 The Horrible Truth__________________________________________________________11 We Have The Right__________________________________________________________14 “Make the most of the Indian Hemp Seed and sow it everywhere.”___________________19 Harm Reduction____________________________________________________________30 Prohibition________________________________________________________________32 Gangster Bureaucrats________________________________________________________40 “Mexico’s a turncoat in the war on drugs.” ______________________________________46 “Politics is broken.” _________________________________________________________51 Attorney General Is Not Required To Be “Learned at Law”_________________________58 After All, It’s A Small World__________________________________________________66 The Circle_________________________________________________________________77 Jimi______________________________________________________________________82 “The Empire never ended.” ___________________________________________________84 “Soft people become hard criminals.” -

Mapping the Life Course Trajectories of Serial Killers

A Perfect Storm: Mapping the Life Course Trajectories of Serial Killers by Sasha Reid A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Applied Psychology and Human Development University of Toronto © Copyright by Sasha Reid, 2019 A Perfect Storm: Mapping the Life Course Trajectories of Serial Killers Sasha Reid PhD., Developmental Psychology Applied Psychology and Human Development University of Toronto 2019 Abstract Since the 1970s, scholars have produced a large body of research attempting to establish the mechanisms by which serial killers come to arrive at a life of repeat fatal violence. Traits such as psychopathy, biomarkers such as abnormal dopamine concentrations, and other developmental correlates such as early family environment have all been offered as proximal explanations for the motivations, psychopathology, and etiology of serial homicide. Unfortunately, however, from the standpoint of developmental psychology, these insights are far too limited in scope. Human thought, functioning, and behaviour are the product of complex reciprocal transactions that occur between the individual and their environment throughout their lifespan. Processes that serve to shape human development include neural plasticity, modifiability, resilience and adaptation, among others. Yet, these vital processes are never discussed in the developmental literature on serial homicide. Additionally, research in this area tends to lack the ‘voice of the killer.’ Instead of as active participants, offenders are viewed as objects of research and as passive participants in their own life experiences. Again, this is problematic from the standpoint of developmental psychology. Every person’s actions are formed by years of contextual experience which reinforce dominant patterns of thinking which eventually come to dominate behaviour.