REDEFINING HOW SUCCESS IS MEASURED in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Learning REDEFINING HOW SUCCESS IS MEASURED in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julia V. Emberley Selected Publications: 1. Books and Edited Journals: Julia V. Emberley, the Testimonial Uncanny: Indigenous St

Julia V. Emberley Selected Publications: 1. Books and Edited Journals: Julia V. Emberley, The Testimonial Uncanny: Indigenous Storytelling, Knowledge and Reparative Practice. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2014. Pbk, 2015. Xiv, 338. Julia V. Emberley, Guest Editor, English Studies in Canada. Special Issue: Skin. 34.1 (2009). Julia V. Emberley, Co-Guest Editors with Dr. R. Kennedy and Dr L. Bell. Special Issue: Testimony and Trauma: New Directions, Australian Humanities Research. 15.3 (2009). Julia V. Emberley, Defamiliarizing the Aboriginal: Cultural Practices and Decolonization in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007. 314 pp. Pbk, 2008. Julia V. Emberley, The Cultural Politics of Fur. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s, 1998. xv, 249 pp. Rpt. Venus and Furs: The Cultural Politics of Fur. London: I. B. Tauris, 1998. Julia V. Emberley, Thresholds of Difference: Feminist Critique, Native Women's Writings, Post-Colonial Theory. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993. xx, 202 pp. 2. Book Chapters: “In/Hospitable ‘Aboriginalities’ in Contemporary Indigenous Women’s Writing.” The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature. Forthcoming. Ed. Cynthia Sugars. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. "Ephemera, Memorialization and Indigenous Women's Visual Sovereignity." First Women and the Politics of Looking. Forthcoming. Eds. Wendy Pearson and Kim Verwaylen. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. Accepted. "The Accidental Witness: Testimonial Discourses, Epistemic Shifts, and Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach." TransCanada Volume III. Eds. Smaro Kamboureli and Chystl Verdun. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier Press, 2014. “Epistemic Heterogeneity: Indigenous Storytelling, Testimonial Practices and the Question of Violence in Indian Residential Schools.” Reconciling Canada. Eds. Jennifer Henderson and Pauline Wakeham. -

2005 International Canadian Summer Institute

2005 INTERNATIONAL CANADIAN SUMMER INSTITUTE 12-24 JULY 2005 ALBERTA, CANADA ORGANIZED BY CANADIAN CONSULATE GENERAL SEATTLE in partnership with and support from GOVERNMENT OF CANADA INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC RELATIONS PACIFIC NORTHWEST CANADIAN STUDIES CONSORTIUM UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA, FACULTE ST JEAN UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE THE BANFF CENTRE GOVERNMENT OF ALBERTA RED CROW COMMUNITY COLLEGE 2005 FACULTY SUMMER RESEARCH INSTITUTE ALBERTA, CANADA 12-24 JULY 2005 TUESDAY 12 JULY 00.00 Participants arrive Calgary International Airport throughout the day; clear Canadian Customs and Immigration (passport required); retrieve luggage Transportation options to University of Calgary: taxi to campus is approximately $40 CDN; Shuttle Express service is approximately $20 CDN - the Shuttle Express stand is located near Meeting Area >C= in the International Arrivals terminal - reservations are not necessary - for more information call 888-438-2992; your destination is: Cascade Hall University of Calgary th 3456 24 Ave NW (at Collegiate Rd) Calgary AB 403-220-3202 (Patricia Glenn / Conference Housing) Free time / self-guided tour of campus / independent meetings with UC colleagues 19.30 Opening Reception and Dinner hosted by the Canadian Consulate General Seattle; Kevin Cook, Political, Economic & Academic Officer The Grad Lounge Third Floor MacEwan Student Centre University of Calgary 403-220-7973 (Carol / Lounge Manager) WEDNESDAY 13 JULY 07.15 Breakfast MacEwan Student Centre University of Calgary 403-220-5541 (Ada -

The World Council of Indigenous Peoples

THE WORLD COUNCIL OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES: AN ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL PROTEST by RISE M. MASSEY B.A. (with Distinction) University of Calgary, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE' UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1986 d)) Rise M. Massey, 1986 9 5 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of foliTiooil fv.'igfrr.<=» The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 >E-6 Y3/8in Abstract In response to an almost universal perception on the part of aboriginal peoples of the injustice done to them by the intrusion and take-over of their territories by immigrant- dominated societies, a number of indigenous peoples' groups have arisen on the international scene. One such transnational non-governmental organization is the World Council of Indigenous Peoples. The objects of this thesis are to recount the conditions that precipitated the need for a transnational indigenous peoples support group, to chronicle the formation and work of the WCIP, and to evaluate the organization in terms of why it has (or has not) been a success and in terms of the extent of its success. -

First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework

First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework February 2002 For further information, contact: Alberta Learning 9 th Floor, Commerce Place 10155-102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L5 Telephone: 780-427-8501 or toll-free in Alberta by dialing 310-0000 Fax: 780-422-0880 This document is available on the Internet at: www.learning.gov.ab.ca ALBERTA LEARNING CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Alberta. Alberta Learning. First Nations, Metis and Inuit education policy framework. ISBN 0-7785-1337-8 1. Indians of North America - Education - Alberta. 2. Education and state - Alberta. I. Title. E 96.65.A3.A333 2002 371.97 Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Introduction 1 Background 2 The Policy Framework 8 Vision 9 Policy Statement 9 Achieving the Vision 10 Goals 11 Principles 14 Strategies 16 Achieving Goal 1 16 Achieving Goal 2 17 Achieving Goal 3 18 Achieving Goal 4 19 Achieving Goal 5 19 Performance Measures 20 Measuring Goal 1 23 Measuring Goal 2 23 Measuring Goal 3 25 Measuring Goal 4 26 Measuring Goal 5 27 Monitoring and Reporting of Results 27 Conclusion 28 Glossary of Key Terms 30 Appendix A: Selected Aboriginal Education Initiatives in Alberta 1987-2001 Appendix B: Demographic Trends Appendix C: Strengthening Relationships: The Government of Alberta’s Aboriginal Policy Framework Appendix D: Strategies and Priorities for Further Consideration - What We Heard from the Native Education Policy Review Advisory Committee Appendix E: Activities in Other Jurisdictions Appendix F: References First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework Acknowledgements Development of the First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework was a collaborative effort among many individuals and organizations across Alberta. -

Cross-Epistemological Feminist Conversations Between Indigenous Canada and South Africa

CROSS-EPISTEMOLOGICAL FEMINIST CONVERSATIONS BETWEEN INDIGENOUS CANADA AND SOUTH AFRICA CROSS-EPISTEMOLOGICAL FEMINIST CONVERSATIONS BETWEEN INDIGENOUS CANADA AND SOUTH AFRICA By JESSIE WANYEKI FORSYTH, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Jessie Wanyeki Forsyth, September 2015 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2015) Hamilton, Ontario (English) TITLE: Cross-Epistemological Feminist Conversations Between Indigenous Canada and South Africa AUTHOR: Jessie Wanyeki Forsyth, Ph.D. (McMaster) SUPERVISOR: Professor Helene Strauss NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 293 ii LAY ABSTRACT This project examines a small selection of the literatures by Indigenous women writers in Canada and black South African women writers to conceptualize anti-oppressive approaches to working across differences in both literary/scholarly and activist/lived contexts. It uses conversation as a critical methodology for engaging four primary texts and practicing an uneasy comparative method based on horizontal forms of juxtaposition rather than vertical relations of evaluative power: Mother to Mother (Sindiwe Magona) and The Book of Jessica (Maria Campbell and Linda Griffiths); and Coconut (Kopano Matlwa) and Monkey Beach (Eden Robinson). The overall aim is to re-imagine forms of engaging across difference along a range of registers – racialization, gender, nation, class, language, and geographical location – that create conditions for more expansive and substantive forms of social justice than are currently visible. The project draws on feminist, Indigenous, postcolonial, critical race, and related areas of scholarship with an orientation towards social justice. iii ABSTRACT This is a project that takes inequality as its starting point to ask not why it persists in all its myriad forms, but rather how we might better understand its resiliency in order to re- orient our responses. -

F:\BOARD of GOVERNORS\MINUTES\May22 2008Opn.Min.Wpd

MINUTES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE BOARD OF GOVERNORS OPEN SESSION HELD THURSDAY, MAY 22, 2008 AT 1:30 P.M. IN THE BOARD ROOM (W646) Present: Robert Turner (Chair), Richard Davidson, Bill Cade, Sheila McHugh, Kevin Nugent (by phone), Leah Fowler, Adam Vossepoel, Shannon Digweed, Jeremiah Merkl, Susan Lea, Doug McArthur, Myles Bourke, Karen Bartsch, Dean Setoguchi, Guy McNab, Grant Pisko, and Rita Law (Secretary) Regrets: Art Bonertz, Kim Kultgen, Jeremy Girard, Claudia Malacrida and Gordon Jong Others: Nancy Walker, Vice-President (Finance & Administration) Andrew Hakin, Vice-President (Academic) Dennis Fitzpatrick, Vice-President (Research) Chris Horbachewski, Vice-President (Advancement) Richard Westlund, Director of Government Relations Bob Cooney, Director, Communications Gloria Roth, Recording Secretary Bob Turner presented Kelly Kennedy a letter of thanks from the Minister of Advanced Education, Doug Horner, as well as a certificate from the Government of Alberta. Bob Turner commented on how much the Board appreciated Kelly Kennedy’s contribution and remarked that he has been a distinguished Governor. Bill Cade thanked Kelly Kennedy for his service to the University and commented on what a mainstay of the John Gill Memorial Walk/Run Kelly was by running 150 laps. Chair Turner and President Cade welcomed two new Governors: Adam Vossepoel and Shannon Digweed. Adam Vossepoel was nominated by the Students’ Union and Shannon Digweed by the Graduate students. Both were presented with a briefcase and pin. Chair Turner introduced and welcomed Marilyn Coley, his assistant at Fraser Milner Casgrain in Edmonton, remarking that she is an outstanding person and a delight to work with. President Cade also welcomed Marilyn to the University. -

Decolonization, Indigenous Internationalism, and the World Council of Indigenous Peoples

Decolonization, Indigenous Internationalism, and the World Council of Indigenous Peoples by Jonathan Crossen A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2014 ©Jonathan Crossen 2014 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation investigates the history of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) and the broader movement of Indigenous internationalism. It argues that Indigenous internationalists were inspired by the process of decolonization, and used its logic to establish a new political identity. The foundation of the WCIP helped create a network of Indigenous peoples that expressed international solidarity between historically unconnected communities. The international efforts of Indigenous activists were encouraged both by personal experiences of international travel and post-secondary education, and by the general growth of international non-governmental organizations during the late twentieth century. The growing importance of international non-governmental organizations helped the WCIP secure funding from international developmental aid agencies, a factor which pushed the organization to increase its focus on apolitical economic development relative to the anti-colonial objectives which inspired its foundation. This dissertation examines how Indigenous international organizations became embroiled in the Cold War conflict in Latin America, and the difficulties this situation posed for both the WCIP and the International Indian Treaty Council. -

Indigenous Studies (PDF

Indigenous Studies Undergraduate Program in Indigenous Studies A university that’s all about you Athabasca University, Canada’s Open University, is the nation’s leading online and distance education university. We’re proud to take education to the people, serving more than 38,000 students in 89 countries worldwide. We offer over 750 courses in more than 90 undergraduate and graduate degree, diploma and certificate programs. Our philosophy is to remove geographical, financial, social and cultural barriers that traditionally limit access to post-secondary achievement. The flexibility of our distance and online learning programs allows you to obtain a quality post-secondary education on your own terms—anywhere, any time. Studying at AU is the perfect way to experience all the advantages of a traditional university in a non-traditional setting, like your home, office or wherever you may find yourself. Undergraduate Program in Indigenous Studies studies, and to enable you to the ability to complete your post- officers, managers The study and learn in environments secondary studies at home in and many others who undergraduate which reflect your true heritage your own community required a degree or just and culture. the option to continue working a course or two in their program in while you earn your degree educational journey. This program will appeal to Indigenous small classes you if you are interested in Our commitment extends personalized tutoring and Studies Indigenous issues and are to creating and providing excellent student support looking for Indigenous Studies courses that are relevant, courses written by Indigenous telephone and online access respectful and meaningful authors. -

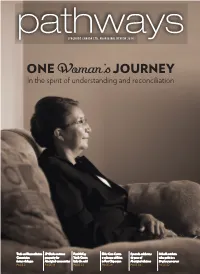

Onewoman'sjourney

pathwaysSYNCRUDE CANADA LTD. ABORIGINAL REVIEW 2014 ONE Woman’s JOURNEY In the spirit of understanding and reconciliation PAGE 2 PAGE 18 PAGE 23 PAGE 28 PAGE 36 PAGE 42 There are many different pathways to success. It could be sitting around a campfire, preparing dry fish and listening to the wisdom of Elders. It could be studying for certification, a college diploma or university degree. Orit could be volunteering for a local grassroots organization. There is no end to the remarkable successes and accomplishments among Aboriginal people in our region, our province and across our country. Pathways captures these stories and connects with First Nations and Métis people making positive contributions in their communities, bringing new perspectives to the table and influencing change in our society. Join us as we explore these many diverse pathways and learn how generations, both young and old, are working to make a difference. WELCOME The stories in Pathways reflect BUSINESS EMPLOYMENT pathways Wood Buffalo is home to some As one of the largest employers the six key commitment areas of the most successful Aboriginal of Aboriginal people in Canada, EDITOR businesses in Canada. Syncrude Syncrude’s goal is to create Mark Kruger that are the focus of Syncrude’s works closely with Aboriginal opportunities that enable business owners to identify First Nations, Métis and EDITORIAL COMMITTEE opportunities for supplying goods Inuit people to fully participate Tara Abraham, Kara Flynn, Maggie Grant, Aboriginal Relations program. and services to our operation. in all aspects of our operation. Lana Hill, Colleen Legdon, These include: Business Development, Christine Simpson, Doug Webb Community Development, Education COMMUNITY ENVIRONMENT WRITERS Canada is a country rich in We are committed to working John Copley, Jasmine Dionne, Maggie Grant, and Training, Employment, the diversity and culture. -

Self-Determination, Colonialism and Pre-Reserve Nehiyaw Forms of Power

Miyo Wahkotowin: Self-determination, Colonialism and Pre-reserve Nehiyaw Forms of Power by Matthew Wildcat B.A. (Hons.), University of Alberta, 2006 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Human and Social Development ! Matthew Wildcat, 2010 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Miyo Wahkotowin: Self-determination, Colonialism and Pre-reserve Nehiyaw Forms of Power by Matthew Wildcat B.A. (Hons.), University of Alberta, 2006 Supervisory Committee Dr. Taiaiake Alfred, (Indigenous Governance Program) Supervisor Dr. Waziyatawin (Indigenous Governance Program) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Taiaiake Alfred, (Indigenous Governance Program) Supervisor Dr. Waziyatawin (Indigenous Governance Program) Departmental Member This thesis explores whether reviving pre-reserve Nehiyaw forms of power represents a strategy of self-determination. To start, an understanding of colonialism is advanced based on the idea that colonialism is an intersectional process that involves both the actions perpetrated from a settler society unto Indigenous peoples, and the legacy of dysfunction that is left with Indigenous peoples as a result of colonization. Second, an understanding of pre-reserve Nehiyaw forms of power is developed, with a focus on how the interaction of legitimacy and authority can be used to explain pre-reserve Nehiyaw forms of power. Finally, I examine if reviving pre-reserve Nehiyaw forms of power represents a strategy of self-determination that addresses the intersectional nature of colonialism. I argue that it does, but in order to revive pre-reserve forms of power we must displace band councils as the site where we imagine a revival of pre-reserve Nehiyaw forms of power. -

Angels Among Us

INSTITUTE FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF ABORIGINAL WOMEN Presents Esquao21st AnnualAwards Angels Among Us FRIDAY, APRIL 15, 2016 RAMADA EDMONTON HOTEL | EDMONTON, ALBERTA Sponsors Acknowledgements ESQUAO AWARDS CO-FOUNDERS Muriel Stanley Venne and Marggo Pariseau PRODUCER Rachelle Venne ORGANIZING TEAM Donna Ahkimnachie, Tina Brett, Cheri Jubinville, Gwen Nahorney, Bernadette Swanson SOUND/EVENT MANAGEMENT Blair McEwen, FM Systems EVENT ASSISTANT Andrea Carroll Papirny, Two Hats Event Management IAAW VIDEO Andy Holt, A-Squared Communication PHOTOGRAPHER Brad Crowfoot VIDEO Evolution Presentation Technologies LIGHTING Production Lighting PROGRAM DESIGN Christine Pearce TELEVISION ShawT V © Esquao is the stylized version for the Cree word for Woman and is copyrighted. 2 21ST ANNUAL ESQUAO AWARDS 2016 Esquao Awards INSTITUTE FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF ABORIGINAL WOMEN We are an Alberta-based non-profit organization, incorporated in 1995. Our head office is in Edmonton with several chapters in Alberta Contents communities. IAAW has over 300 members and 400 Esquao Award and Circle of Honour recipients from over 90 communities. MISSION STATEMENT MESSAGES 4-5 We honour the “Angels Among Us” – Aboriginal women who have played a largely unsung role in society. We reach out to Aboriginal women in Alberta, recognizing them for their significant accomplishments in their AWARD RECIPIENTS 6-9 communities. We provide opportunities for Aboriginal women through educational and self-development programs. MASTERS OF CEREMONY 10 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Acknowledgements -

Fifty Western Chiefs Refuse to Give up Rights

Alberta leads way on C -31 membership codes By Jamie McDonell Register) unjustly, they can be used to restrict their Northern Alberta Indian descendents. bands have led the way in The question in Alberta taking control of their is, for the present, academic membership under Bill since only two individuals C -31. have asked to return to their ancestral reserve (as Seven of the first 12 bands to establish band compared with 469 in B.C., 290 in Manitoba and in LOVED ONES REMEMBERED IN SADDLE LAKE membership codes in 193 Quebec). response to Bill C -31 are A memorial dance was held with the give -away dance during the Saddle Lake Powwow, held June 26, 27 and Besides Sawridge, other from northern Alberta, two 28. The Whiskeyjack family and relatives mourned the loss of Kathleen and Emma Whiskeyjack, who passed Alberta bands that have are from B.C., two from away two years ago within 12 days of each other. On the right is Caroline Whiskeyjack and behind her is Alsena assumed control of their Ontario and one from Whiskeyjack. A memorial dinner was also hosted before the powwow grand entry. Saskatchewan. membership codes are Lubicon, Swan River, The first band in the Horse Lake, Ermineskin, country to take control of Driftpile and Fort its membership was the McMurray. Sawridge band of Slave As of June 28, the closing INSIDE THIS WEEK Lake. Its membership code date for the government's went into effect July 8, 1985 moratorium on additions to -- less than two weeks after band lists, 26 in Alberta's 43 C -31 provisions allowing bands (and 149 of 615 Education IAA's Morley Land claim bands to establish codes across the country) had cuts went into effect.