Writing Activism: Indigenous Newsprint Media in the Era of Red Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

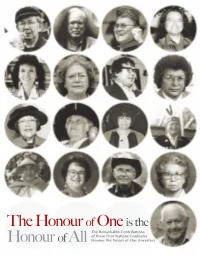

The Honour of One Is the the Remarkable Contributions of These First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors Table of Contents of Table

The Honour of One is the The Remarkable Contributions of these First Nations Graduates Honour of All Honour the Voices of Our Ancestors 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Table of Contents 3 Table of Contents 2 THE HONOUR OF ONE Introduction 4 William (Bill) Ronald Reid 8 George Manuel 10 Margaret Siwallace 12 Chief Simon Baker 14 Phyllis Amelia Chelsea 16 Elizabeth Rose Charlie 18 Elijah Edward Smith 20 Doreen May Jensen 22 Minnie Elizabeth Croft 24 Georges Henry Erasmus 26 Verna Jane Kirkness 28 Vincent Stogan 30 Clarence Thomas Jules 32 Alfred John Scow 34 Robert Francis Joseph 36 Simon Peter Lucas 38 Madeleine Dion Stout 40 Acknowledgments 42 4 THE HONOUR OF ONE IntroductionIntroduction 5 THE HONOUR OF ONE The Honour of One is the Honour of All “As we enter this new age that is being he Honour of One is the called “The Age of Information,” I like to THonour of All Sourcebook is think it is the age when healing will take a tribute to the First Nations men place. This is a good time to acknowledge and women recognized by the our accomplishments. This is a good time to University of British Columbia for share. We need to learn from the wisdom of their distinguished achievements and our ancestors. We need to recognize the hard outstanding service to either the life work of our predecessors which has brought of the university, the province, or on us to where we are today.” a national or international level. Doreen Jensen May 29, 1992 This tribute shows that excellence can be expressed in many ways. -

Julia V. Emberley Selected Publications: 1. Books and Edited Journals: Julia V. Emberley, the Testimonial Uncanny: Indigenous St

Julia V. Emberley Selected Publications: 1. Books and Edited Journals: Julia V. Emberley, The Testimonial Uncanny: Indigenous Storytelling, Knowledge and Reparative Practice. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2014. Pbk, 2015. Xiv, 338. Julia V. Emberley, Guest Editor, English Studies in Canada. Special Issue: Skin. 34.1 (2009). Julia V. Emberley, Co-Guest Editors with Dr. R. Kennedy and Dr L. Bell. Special Issue: Testimony and Trauma: New Directions, Australian Humanities Research. 15.3 (2009). Julia V. Emberley, Defamiliarizing the Aboriginal: Cultural Practices and Decolonization in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007. 314 pp. Pbk, 2008. Julia V. Emberley, The Cultural Politics of Fur. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s, 1998. xv, 249 pp. Rpt. Venus and Furs: The Cultural Politics of Fur. London: I. B. Tauris, 1998. Julia V. Emberley, Thresholds of Difference: Feminist Critique, Native Women's Writings, Post-Colonial Theory. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993. xx, 202 pp. 2. Book Chapters: “In/Hospitable ‘Aboriginalities’ in Contemporary Indigenous Women’s Writing.” The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature. Forthcoming. Ed. Cynthia Sugars. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. "Ephemera, Memorialization and Indigenous Women's Visual Sovereignity." First Women and the Politics of Looking. Forthcoming. Eds. Wendy Pearson and Kim Verwaylen. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. Accepted. "The Accidental Witness: Testimonial Discourses, Epistemic Shifts, and Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach." TransCanada Volume III. Eds. Smaro Kamboureli and Chystl Verdun. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier Press, 2014. “Epistemic Heterogeneity: Indigenous Storytelling, Testimonial Practices and the Question of Violence in Indian Residential Schools.” Reconciling Canada. Eds. Jennifer Henderson and Pauline Wakeham. -

Introduction One Setting the Stage

Notes Introduction 1. For further reference, see, for example, MacKay 2002. 2. See also Engle 2010 for this discussion. 3. I owe thanks to Naomi Kipuri, herself an indigenous Maasai, for having told me of this experience. 4. In the sense as this process was first described and analyzed by Fredrik Barth (1969). 5. An in-depth and updated overview of the state of affairs is given by other sources, such as the annual IWGIA publication, The Indigenous World. 6. The phrase refers to a 1972 cross-country protest by the Indians. 7. Refers to the Act that extinguished Native land claims in almost all of Alaska in exchange for about one-ninth of the state’s land plus US$962.5 million in compensation. 8. Refers to the court case in which, in 1992, the Australian High Court for the first time recognized Native title. 9. Refers to the Berger Inquiry that followed the proposed building of a pipeline from the Beaufort Sea down the Mackenzie Valley in Canada. 10. Settler countries are those that were colonized by European farmers who took over the land belonging to the aboriginal populations and where the settlers and their descendents became the majority of the population. 11. See for example Béteille 1998 and Kuper 2003. 12. I follow the distinction as clarified by Jenkins when he writes that “a group is a collectivity which is meaningful to its members, of which they are aware, while a category is a collectivity that is defined according to criteria formu- lated by the sociologist or anthropologist” (2008, 56). -

Download Download

Generations and the Transformation of Social Movements in Postwar Canada DOMINIQUE CLE´ MENT* Historians, particularly in Canada, have yet to make a significant contribution to the study of contemporary social movements. State funding, ideological conflict, and demographic change had a critical impact on social movements in Canada in the 1960s and 1970s, as this case study of the Ligue des droits de l’homme (Montreal) shows. These developments distinguished the first (1930s–1950s) from the second (1960s–1980s) generation of rights associations in Canada. Generational change was especially pronounced within the Ligue. The demographic wave led by the baby boomers and the social, economic, and political contexts of the period had a profound impact on social movements, extending from the first- and second-generation rights associations to the larger context including movements led by women, Aboriginals, gays and lesbians, African Canadians, the New Left, and others. Les historiens, en particulier au Canada, ont peu contribue´ a` ce jour a` l’e´tude des mouvements sociaux contemporains. Le financement par l’E´ tat, les conflits ide´olo- giques et les changements de´mographiques ont eu un impact de´cisif sur les mouve- ments sociaux au Canada lors des anne´es 1960 et 1970, comme le montre la pre´sente e´tude de cas sur la Ligue des droits de l’homme (Montre´al). Ces de´veloppements ont distingue´ les associations de de´fense des droits de la premie`re ge´ne´ration (anne´es 1930 aux anne´es 1950) de ceux de la deuxie`me ge´ne´ration (anne´es 1960 aux anne´es 1980) au Canada. -

The Spirit and Intent of Treaty Eight: a Sagaw Eeniw Perspective

The Spirit and Intent of Treaty Eight: A Sagaw Eeniw Perspective A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Masters Degree in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sheldon Cardinal Fall 2001 © Copyright Sheldon Cardinal, 2001. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for a graduate degree from the University ofSaskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries ofthis University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying ofthis thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head ofthe Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use ofthis thesis orparts thereoffor financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use ofmaterial in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: The Dean, College ofLaw University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N5A6 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number ofpeople that I would like to thank for their assistance and guidance in completing my thesis. First, I would like to acknowledge my family. My parents, Harold and Maisie Cardinal have always stressed the importance ofeducation. -

Volume 13 No. 3

Nikkei Images National Nikkei Museum and Heritage Centre Newsletter ISSN#1203-9017 Fall 2008, Vol. 13, No. 3 The ‘River Garage’ by Theodore T. Hirota My father the foot of Third Hayao Hirota was Avenue it spread born on January e a s t w a r d a w a y 25, 1910, in the from the Canadian small fishing vil- Fishing Company’s lage of Ladner, Gulf of Georgia located on the Cannery and burned left bank of the down the Star, Ste- Fraser River in veston, and Light- British Columbia house Canneries as just a few miles well as the London, from where the Richmond, and Star river empties into Hotels before the the Gulf of Geor- fire was stopped at gia. On the right Number One Road. bank of the lower The walls of the arm of the Fraser The Walker Emporium hardware store catered to Steveston’s fishing Hepworth Block industry in the early 1900s. (Photo courtesy T. Hirota) River and right remained the only at the mouth of Block reputedly were ballast from structure left stand- the river, another fishing village, the early sailing ships and were ing on the entire south side of Steveston, was home to 14 salmon replaced by canned salmon on the Moncton Street. All that was left fishing canneries in 1900. return trip to Britain. along the waterfront after the fire At the time of my father’s When a fire broke out were row upon rows of blackened birth, a substantial hardware store at the Star Cannery’s Chinese pilings. -

“In Principle”: Sto:Lo Political Organizations and Attitudes Towards Treaty Since 1969

“In Principle”: Sto:lo Political Organizations and Attitudes Towards Treaty Since 1969 By Byron Plant Term Paper History 526 May 6 - June 7 2002 Sto:lo Ethnohistory Field School Instructors: Dr. John Lutz and Keith Carlson Due: Friday, 5 July 2002 1 This essay topic was initially selected from those compiled by the Sto:lo Nation and intended to examine Sto:lo attitudes towards treaty since 1860. While certainly a pertinent and interesting question to examine, two difficulties arose during my initial research. One was the logistical question of condensing a century and a half of change into such a short paper while at the same time giving due consideration to the many social, political, and economic changes of that time. Two, little to no work has been done on tracing how exactly Sto:lo political attitudes have been voiced over time. While names such as the East Fraser District Council, Chilliwack Area Indian Council, and Coqualeetza regularly appear throughout documentary and oral sources, no one has actually outlined what these organizations were, why they formed, and where they went. Consequently, through consultation and several revisions with Dave Smith, Keith Carlson, and John Lutz, the scope of the paper was narrowed down to the period from 1969 to the present and opened up to questions about Sto:lo political and administrative organizations. Through study of the motivations, ideals, and legacies of these organizations and their participants, I hope to then examine treaty attitudes and to what extent treaties influenced Sto:lo political activity over the past thirty years. In hindsight, I can see how study of any individual Sto:lo organization is capable of constituting a full paper in itself. -

Community Economic Development ~ Indigenous Engagement Strategy for Momentum, Calgary Alberta 2016

Community Economic Development ~ Indigenous Engagement Strategy for Momentum, Calgary Alberta 2016 1 Research and report prepared for Momentum by Christy Morgan and Monique Fry April 2016 2 Executive Summary ~ Momentum & Indigenous Community Economic Development: Two worldviews yet working together for change Momentum is a Community Economic Development (CED) organization located in Calgary, Alberta. Momentum partners with people living on low income to increase prosperity and support the development of local economies with opportunities for all. Momentum currently operates 18 programs in Financial Literacy, Skills Training and Business Development. Momentum began the development of an Indigenous Engagement Strategy (IES) in the spring of 2016. This process included comparing the cultural elements of the Indigenous community and Momentum’s programing, defining success, and developing a learning strategy for Momentum. Data was collected through interviews, community information sessions, and an online survey. The information collected was incorporated into Momentum’s IES. Commonalities were identified between Momentum’s approach to CED based on poverty reduction and sustainable livelihoods, and an Indigenous CED approach based on cultural caring and sharing for collective wellbeing. Both approaches emphasize changing social conditions which result in a community that is better at meeting the needs of all its members. They share a focus on local, grassroots development, are community orientated, and are holistic strength based approaches. The care taken by Momentum in what they do and how they do it at a personal, program and organizational level has parallels to the shared responsibility held within Indigenous communities. Accountability for their actions before their stakeholders and a deep-rooted concern for the wellbeing of others are keystones in both approaches. -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award ................................................................................................. -

2005 International Canadian Summer Institute

2005 INTERNATIONAL CANADIAN SUMMER INSTITUTE 12-24 JULY 2005 ALBERTA, CANADA ORGANIZED BY CANADIAN CONSULATE GENERAL SEATTLE in partnership with and support from GOVERNMENT OF CANADA INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC RELATIONS PACIFIC NORTHWEST CANADIAN STUDIES CONSORTIUM UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA, FACULTE ST JEAN UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE THE BANFF CENTRE GOVERNMENT OF ALBERTA RED CROW COMMUNITY COLLEGE 2005 FACULTY SUMMER RESEARCH INSTITUTE ALBERTA, CANADA 12-24 JULY 2005 TUESDAY 12 JULY 00.00 Participants arrive Calgary International Airport throughout the day; clear Canadian Customs and Immigration (passport required); retrieve luggage Transportation options to University of Calgary: taxi to campus is approximately $40 CDN; Shuttle Express service is approximately $20 CDN - the Shuttle Express stand is located near Meeting Area >C= in the International Arrivals terminal - reservations are not necessary - for more information call 888-438-2992; your destination is: Cascade Hall University of Calgary th 3456 24 Ave NW (at Collegiate Rd) Calgary AB 403-220-3202 (Patricia Glenn / Conference Housing) Free time / self-guided tour of campus / independent meetings with UC colleagues 19.30 Opening Reception and Dinner hosted by the Canadian Consulate General Seattle; Kevin Cook, Political, Economic & Academic Officer The Grad Lounge Third Floor MacEwan Student Centre University of Calgary 403-220-7973 (Carol / Lounge Manager) WEDNESDAY 13 JULY 07.15 Breakfast MacEwan Student Centre University of Calgary 403-220-5541 (Ada -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

Hockey in Wartime Canada, 1939-1945

FOR CLUB OR COUNTRY? HOCKEY IN WARTIME CANADA, 1939-1945 BY Gabriel Stephen Panunto, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Carleton University Ottawa Ontario July 19, 2000 Q copyright 2000 Gabriel Stephen Panunto National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*I of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KtA ON4 OnawaON KlAON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Sports reflect the societies that support them, and hockey in Canada during World War Two is no exception. Popular hockey history has defined the era as one of great sacrifices by the National Hockey League. largely because academic research is non- existent.