SCAN | Journal of Media Arts Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled, Digital Print and Oil on Canvas, 11 ¼ X 9 3/16 In

Authenticity, Originality and the Copy: Questions of Truth and Authorship in the Work of Mark Landis, Elizabeth Durack, and Richard Prince A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Art History Program of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning April 2012 by Rebekah Catherine Shipe BA, Lycoming College, 2009 Committee Chair: Morgan Thomas, Ph.D. Reader: Kimberly Paice, Ph.D. Reader: Vincent Sansalone Abstract As contemporary artists transgress accepted definitions of authenticity and challenge ideas of originality and creativity, we must re-evaluate our understanding of these concepts. By focusing on three illuminating case studies, I examine how recent practices complicate basic concepts of authorship and artistic truth. Chapter One explores the case of art forger, Mark Landis (b. 1955), to illuminate the ambiguity of the copy and the paradoxical aura of forgeries in the wake of postmodernism. Focusing on the case of Australian artist Elizabeth Durack (1915-2000), who created and exhibited paintings under the fictitious persona of an Aboriginal artist, Eddie Burrup, Chapter Two links the controversies surrounding her work to key theoretical explorations of aura, reproducibility, and originality. Chapter Three deals with the self-conscious deployment of postmodern notions of originality and authorship in the re-photographed photographs of notorious ‘appropriation artist’ Richard Prince (b. 1949). The thesis aims to draw out a number of key patterns with regard to notions of the copy, authenticity, and originality in contemporary culture: the slipperiness of the line drawn between the fake and the original (for example, a kind of excess of ‘uniqueness’ that carries over into the copy); the material interplay between ‘old’ technologies such as painting and new reproductive (e.g. -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Pieces 1990 - 2005 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KILL ALL YOUR DARLINGS: PIECES 1990 - 2005 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Luc Sante,Greil Marcus | 304 pages | 18 Oct 2007 | Puncture Publications | 9781891241536 | English | Portland, United States Kill All Your Darlings: Pieces 1990 - 2005 PDF Book Added to Watchlist. Call us on or send us an email at. Jan 23, David rated it really liked it Shelves: anthologies-and-collections , read-in , unexpectedly-terrific. If he were in my arts weekly, I'd read him every week and it probably wouldn't change my consumption patterns at all. My thoughts on why Luc Sante is annoying TK. If I pitched you a story about the Beat generation led by Harry Potter, the new Harry Osborne, a guy from X-Men and the guy from Boardwalk Empire with half his face missing, I'm sure the reaction would be pretty great. Would like to read his other book, Low Life. May 20, Paul Bryant rated it liked it Shelves: autobiography-memoir. Permissions Librarian Erin Darke Apr 01, Valentine Valentino rated it really liked it. View 2 comments. Kill Your Darlings repeats the initial reaction to Carr's response to Ginsberg's complicated life, "Perfect. Color: Color. If this item isn't available to be reserved nearby, add the item to your basket instead and select 'Deliver to my local shop' at the checkout, to be able to collect it from there at a later date. When he's on which is most of the time here , he creates vivid images and ideas that perfectly describe what he's talking about -- whether it be New York, the invention of the blues, Bob Dylan, or visual art. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Distributed Art Publishers, Inc. 155 Sixth Avenue New York NY 10013 Tel: 212 627-1999 Fax: 800-478-3128

Distributed Art Publishers, Inc. 155 Sixth Avenue New York NY 10013 Tel: 212 627-1999 Fax: 800-478-3128 Fall/Winter 2009 Title Supplement GENERAL INTEREST T. Adler Books/Stonemaster Press The Stonemasters: California Rock Climbing 1970-1980 Text by John Long, Dean Fidelman. In the early 1970s, a small band of young rock climbers, decked out in bandanas, shades and cut-offs, came together and blew open the conventions of climbing. Dubbing themselves the Stonemasters, these now legendary adventurers established techniques that allowed for some of the most spectacular climbs to be done with a minimum of apparatus. Beyond their unsurpassed skills as climbers, the Stonemasters embodied a lifestyle--they were loud, proud, smoked dope, chalked their lightning-flash insignia across rockfaces, took the light stuff seriously and the serious stuff lightly--and the glamour of this lifestyle made a massive impact on 1970s youth culture across the world. Among the first Stonemasters were Rick Accomazzo, Richard Harrison, Mike Graham, Robs Muir, Gib Lewis, Bill Antel, Jim Hoagland, Tobin Sorenson, John Bachar and John Long, but the character or myth of the Stonemaster caught on like wildfire, spreading from coast to coast and across the ocean, and spawning Stonemasters everywhere. Here, Dean Fidelman's thrilling archival photos reveal for the first time an era defined by risk, camaraderie and non-conformity. Tales from original Stonemaster John Long and others recall the highs and lows of the early days--a magical time in the annals of adventure sports--in this exciting and beautifully produced volume. The Stonemasters: California Rock Climbing 1970-1980 ISBN 978-0-9840949-0-5 Hbk, 10 x 12 in. -

Artists Among Us Media Alert FINAL

ARTISTS AMONG US, THE WHITNEY'S FIRST-EVER PODCAST WITH HOST CARRIE MAE WEEMS, DEBUTS MAY 14 Debuting on May 14, the five-episode podcast responds to and expands upon David Hammons's Day's End NEW YORK, May 3, 2021 – On May 14, 2021, the Whitney Museum of American Art will launch its first-ever podcast Artists Among Us. Consisting of five episodes, Artists Among Us is hosted by influential artist and photographer Carrie Mae Weems and features both expected and unexpected voices. Created by the Whitney with Sound Made Public, podcast episodes respond to and expand upon David Hammons’s permanent public sculpture Day’s End (2014-21). Artists Among Us not only explores the work of Hammons, but it also pays tribute to Gordon Matta- Clark and his visionary sculpture Day’s End (1975) and delves into the many histories and changing landscapes of the Hudson River waterfront and New York’s Meatpacking District. Along with Weems, contributing voices include Jane Crawford, Tom Finkelpearl, Bill T. Jones, Kellie Jones, Glenn Ligon, Alan Michelson, Florent Morellet, Luc Sante, Adam D. Weinberg, and others. “Day’s End doesn’t have any one story to tell, any single history that it celebrates,” says Carrie Mae Weems, host of the podcast. “It’s an absence, a frame of a building that no longer exists. But it’s so rooted in its site at the meeting point of the city and the river that we might also see that absence as an opening—a space for the many absences and invisible histories of this place to speak.” “Hammons’s sculpture is so simple in its outlines but so rich in its meanings and in the stories it evokes,” said Anne Byrd, director of interpretation and research at the Whitney. -

The Lives of John Lennon Free

FREE THE LIVES OF JOHN LENNON PDF Albert Goldman | 719 pages | 01 Dec 2001 | Chicago Review Press | 9781556523991 | English | Chicago, United States Rock from a hard place | Music books | The Guardian His songwriting partnership with Paul McCartney remains the most successful in musical history. After the Beatles disbanded inLennon continued a career as a solo artist and as Ono's collaborator. Born in LiverpoolLennon became involved in the skiffle craze as a teenager. Inhe formed his first band, the Quarrymenwhich evolved into the Beatles in He was initially the group's de facto leader, a role gradually ceded to McCartney. Lennon was characterised for the rebellious nature and acerbic wit in his music, writing, drawings, on film and in interviews. In the mids, he had two books published: In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Worksboth collections of nonsense writings and line drawings. Starting with 's " All You Need Is Love ", his songs were adopted as anthems by the anti-war movement and the larger counterculture. Inhe held the two week-long anti-war demonstration Bed-Ins for Peace. After moving to New York City inhis criticism of the Vietnam War resulted in a three-year attempt by the Nixon administration to deport him. InLennon disengaged from the music business to raise his infant son Sean and, inreturned with the Ono collaboration Double Fantasy. He was shot and killed in the archway of his Manhattan apartment building by a Beatles fan, Mark David Chapmanthree weeks after the album's release. As a performer, writer or co-writer, Lennon had 25 number one singles in the Billboard The Lives of John Lennon chart. -

The Moravian Night a Story Peter Handke; Translated from the German by Krishna Winston

Here I Am A Novel Jonathan Safran Foer A monumental new novel from the bestselling author of Everything Is Illuminated and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close In the book of Genesis, when God calls out, “Abraham!” to order him to sacrifice his son Isaac, Abraham responds, “Here I am.” Later, when Isaac calls out, “My father!” to ask him why there is no animal to slaughter, Abraham responds, “Here I am.” How do we fulfill our conflicting duties as father, husband, and son; wife and mother; child and adult? Jew and American? How can we claim our own identities when our lives are linked so closely to others’? These are FICTION the questions at the heart of Jonathan Safran Foer’s first novel in eleven years--a work of extraordinary scope and heartbreaking intimacy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 9/6/2016 9780374280024 | $28.00 / $31.50 Can. Unfolding over four tumultuous weeks, in present-day Washington, D.C., Hardcover | 592 pages Carton Qty: 0 | 9 in H | 6 in W Here I Am is the story of a fracturing family in a moment of crisis. As Brit., trans., 1st ser., dram.: Aragi, Inc. Jacob and Julia and their three sons are forced to confront the distances Audio: FSG between the lives they think they want and the lives they are living, a catastrophic earthquake sets in motion a quickly escalating conflict in the MARKETING Middle East. At stake is the very meaning of home--and the fundamental question of how much life one can bear. Author Tour National Publicity National Advertising Showcasing the same high-energy inventiveness, hilarious irreverence, Web Marketing Campaign and emotional urgency that readers and critics loved in his earlier work, Library Marketing Campaign Reading Group Guide Here I Am is Foer’s most searching, hard-hitting, and grandly entertaining Advance Reader's Edition novel yet. -

The Nature of Photographs

t The Nature of Photographs By Stephen Shore A Primer :i ', ",]]],l:,:.':,J!",,, PHAIDoN ry!Uuuu,,.,,,,,, , Tn The Nature of Photographs, Stephen Shore explores ways of understanding and ]ooking at all types of photographs - from iconic images to found pictures, negatives to digital fí]es. Based on Shorers many years of teaching photography at Bard College, New York State, this book serves as an indispensable tool for students, teachers and everyone who wants to take better pictures or learn to ]_ook at them in a more informed wav. As we]l as a selection of shorers own work, The }trature of Photographs contains images from throughout the history of photograph;r, from works by the fathers of photography such as Alfred Stieglitz and walker Evans to that of artists working with the medium today such as Co]lier Schorr and Thomas Struth. rt covers a range of genres, such as street photography, fine art photography and documentary photography, as well as images by unknown photographers, be they in the form of an old snapshot or an aerial photograph taken as part of a geographical survey. Together with his clear, intelligent and accessible text, shore uses these works to demonstrate how the world in front of the camera is transformed into a photograph. Jacket iL}ustration: Kenneth Josephson New york state !,97 0 The Nature of Photographs phaidon press Limited Regent's Wharf A11 Sain]:s Slreet London Nt 9PA Phaidon Press Tnc. 1B0 Varick Streel New York, NY t0014 www.phaidon.com Second edition (revised, expanded and redesigned) @ 2a07 Phaidon Press Limited Reprinled 20O7 First edilion published by The Johns Hopkins University Press ISBN 97B 0 71,4B 1585 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is a"vaiLable from ihe Bri]:ish Library. -

May 17, 2018 Why the LPC Needs a Qualified Chair That Respects Its

184 Bowery, #4 New York, NY 10012 www.boweryalliance.org David Mulkins, President [email protected] 631-901-5435 President David Mulkins May 17, 2018 Vice Presidents Michele Campo Why the LPC needs a qualified Chair that respects its mission to Jean Standish safeguard the city’s historical, cultural and architectural heritage Secretary Sally Young Dear Mayor de Blasio, Deputy Mayor Glen and Speaker Johnson, Treasurer Jean Standish My name is David Mulkins. In addition to teaching high school history in Landmarks Committee Chair NYC for 25 years, I’m a 37-year resident of the Lower East Side and co- Mitchell Grubler founder of the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, a non-profit grassroots Co-Founders organization working to protect residents, small businesses and the Anna L. Sawaryn historic character of the Bowery, which is New York City’s oldest street. David Mulkins BAN formed in 2007 in reaction to out of scale development and the destruction of some of the area’s oldest structures. In addition to getting the Bowery Historic District listed on both the State and Board of Advisors: National Register of Historic Places, we recently launched Windows Simeon Bankoff on the Bowery, a highly praised series of 64 historic signage posters Executive Director Historic Districts Council displayed in storefronts up and down the Bowery. Kent Barwick President Emeritus In September 2017, the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, with support from Municipal Arts Society Historic Districts Council; author Anthony C. Wood (Preserving New Leo Blackman York), Andrew Dolkart (Prof of Historic Preservation, Columbia Architect University) and former LPC Chair Kent Barwick, submitted an RFE to the Kerri Culhane LPC for a modest 2.5 block stretch of the Bowery. -

2020 Bard College Awards Program

BARD COLLEGE ONE HUNDRED SIXTIETH COMMENCEMENT The Bard College Awards Ceremony Saturday the twenty-second of August two thousand twenty 11:00 a.m. Commencement Tent, Seth Goldfine Memorial Rugby Field Annandale-on-Hudson, New York PROGRAM Welcome Jane Andromache Brien ’89 Director, Alumni/ae Affairs, Bard College KC Serota ’04 President, Board of Governors, Bard College Alumni/ae Association Remarks James C. Chambers ’81 Chair, Board of Trustees, Bard College Recognition of Reunion Classes 1950, 1955, 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 Remarks Leon Botstein President, Bard College The Bard Medal Barbara S. Grossman ’73 Elizabeth Ely ’65 Robert Kelly Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor The John and Samuel Bard Award in Medicine and Science Juliet Morrison ’03 Roger N. Scotland ’93 Felicia Keesing Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor The Charles Flint Kellogg Award in Arts and Letters Xaviera Simmons ’05 Mostafiz ShahMohammed ’97 An-My Lê Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor The John Dewey Award for Distinguished Public Service Nicholas Ascienzo Fiona Angelini Jonathan Becker Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor Matthew Taibbi ’92 Andrew S. Gundlach Wyatt Mason Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor The Mary McCarthy Award Carolyn Forché Emily H. Fisher Dinaw Mengestu Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor The Bardian Award Peggy Ahwesh James von Klemperer Jacqueline Goss Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor Matthew Deady David E. Schwab II ’52 Ethan D. Bloch Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor Bonnie R. Marcus ’71 Stanley A. Reichel ’65 Janet Stetson ’81 Trustee Sponsor Director of Graduate Admission Richard Teitelbaum Charles S. Johnson III ’70 Joan Tower Trustee Sponsor Faculty Sponsor Closing KC Serota ’04 THE BARD MEDAL Barbara S. -

PDF Linked Here

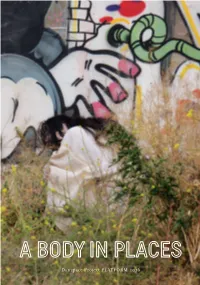

Danspace Project PLATFORM 2016 Published by Danspace Project, New BOARD OF DIRECTORS York, on the occasion of PLATFORM 2016: A Body in Places curated by Judy President: David Fanger Hussie-Taylor and Lydia Bell in First Vice President: Helen Warwick collaboration with Eiko Otake. Second Vice President: Frances Milberg Treasurer: Sam Miller First edition Secretary: David Parker ©2016 Danspace Project Mary Barone Trisha Brown, Emeritus All rights reserved under pan-Ameri- Douglas Dunn, Emeritus can copyright conventions. No part of Hilary Easton this publication may be reproduced or Ishmael Houston-Jones, Emeritus utilized in any form or by any means Judy Hussie-Taylor without permission in writing from the Nicole LaRusso publisher. Ralph Lemon, Emeritus Every reasonable effort has been made Bebe Miller, Emeritus to identify owners of copyright. Errors Sarah Skaggs or omissions will be corrected in subse- Linda Stein quent editions. Laurie Uprichard Nina Winthrop Inquires should be addressed to: Danspace Project St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery 131 East 10th Street New York, NY 10003 danspaceproject.org Editor-in-Chief Judy Hussie-Taylor Editor Lydia Bell Curatorial Fellow Jaime Shearn Coan Designer Judith Walker Publisher Danspace Project Saint Marks Church in-the-Bowery 131 East 10th Street New York, NY 10003 (212) 674 8112 Danspace Project PLATFORM 2016 TEXTS 7 94 EIKO TAKES HER PLACE A BODY LANGUAGE Judy Hussie-Taylor Forrest Gander 13 97 EIKO IN PLACE MY LOST CITY Harry Philbrick Luc Sante 21 109 CONVERSATION CONVERSATION Lydia Bell, Michelle Boulé, Trajal Harrell, Sam Miller and Eiko Otake David Brick, Neil Greenberg, Moderated by Lydia Bell and Judy Hussie-Taylor, Judy Hussie-Taylor Mark McCloughan, Eiko Otake, Koma Otake 121 and Valda Setterfield NOTHING IS ORDINARY Eiko Otake 35 THREE WOMEN 129 Eiko Otake WANDERLUSTING Paul Chan 39 A BODY ON THE LINE 135 Rosemary Candelario PLATFORM PROGRAM 90 146 OBSCURITY AND EMPATHY BIOGRAPHIES OBSCURITY AND SHELTER C.D.