PDF Linked Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled, Digital Print and Oil on Canvas, 11 ¼ X 9 3/16 In

Authenticity, Originality and the Copy: Questions of Truth and Authorship in the Work of Mark Landis, Elizabeth Durack, and Richard Prince A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Art History Program of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning April 2012 by Rebekah Catherine Shipe BA, Lycoming College, 2009 Committee Chair: Morgan Thomas, Ph.D. Reader: Kimberly Paice, Ph.D. Reader: Vincent Sansalone Abstract As contemporary artists transgress accepted definitions of authenticity and challenge ideas of originality and creativity, we must re-evaluate our understanding of these concepts. By focusing on three illuminating case studies, I examine how recent practices complicate basic concepts of authorship and artistic truth. Chapter One explores the case of art forger, Mark Landis (b. 1955), to illuminate the ambiguity of the copy and the paradoxical aura of forgeries in the wake of postmodernism. Focusing on the case of Australian artist Elizabeth Durack (1915-2000), who created and exhibited paintings under the fictitious persona of an Aboriginal artist, Eddie Burrup, Chapter Two links the controversies surrounding her work to key theoretical explorations of aura, reproducibility, and originality. Chapter Three deals with the self-conscious deployment of postmodern notions of originality and authorship in the re-photographed photographs of notorious ‘appropriation artist’ Richard Prince (b. 1949). The thesis aims to draw out a number of key patterns with regard to notions of the copy, authenticity, and originality in contemporary culture: the slipperiness of the line drawn between the fake and the original (for example, a kind of excess of ‘uniqueness’ that carries over into the copy); the material interplay between ‘old’ technologies such as painting and new reproductive (e.g. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, wfiMe others may be from any type of computer printer. Tfie quality of this reproducthm Is dependent upon ttie quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, ootored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleodthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wiU be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to t>e removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at ttie upper left-tiand comer and continuing from left to rigtit in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have t>een reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higtier qualify 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any pfiotographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional ctiarge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMT CHILDREN'S DANCE: AN EXPLORATION THROUGH THE TECHNIQUES OF MERGE CUNNINGHAM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sharon L. Unrau, M.A., CM.A. The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Emeritus Philip Clark Professor Seymour Kleinman, Advisor Assistant Professor Fiona Travis UMI Number 9962456 Copyright 2000 by Unrau, Sharon Lynn All rights reserved. -

Download the DRUMS of Chick Webb

1 The DRUMS of WILLIAM WEBB “CHICK” Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 16, 2021 2 Born: Baltimore, Maryland, Feb. 10, year unknown, 1897, 1902, 1905, 1907 and 1909 have been suggested (ref. Mosaic’s Chick Webb box) Died: John Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, June 16, 1939 Introduction: We loved Chick Webb back then in Oslo Jazz Circle. And we hated Ella Fitzgerald because she sung too much; even took over the whole thing and made so many boring records instead of letting the band swing, among the hottest jazz units on the swing era! History: Overcame physical deformity caused by tuberculosis of the spine. Bought first set of drums from his earnings as a newspaper boy. Joined local boys’ band at the age of 11, later (together with John Trueheart) worked in the Jazzola Orchestra, playing mainly on pleasure steamers. Moved to New York (ca. 1925), subsequently worked briefly in Edgar Dowell’s Orchestra. In 1926 led own five- piece band at The Black Bottom Club, New York, for five-month residency. Later led own eight-piece band at the Paddocks Club, before leading own ‘Harlem Stompers’ at Savoy Ballroom from January 1927. Added three more musicians for stint at Rose Danceland (from December 1927). Worked mainly in New York during the late 1920s – several periods of inactivity – but during 1928 and 1929 played various venues including Strand Roof, Roseland, Cotton Club (July 1929), etc. During the early 1930s played the Roseland, Sa voy Ballroom, and toured with the ‘Hot Chocolates’ revue. From late 1931 the band began playing long regular seasons at the Savoy Ballroom (later fronted by Bardu Ali). -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Download PDF 3.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Eiko and Koma: Dance Philosophy and Aesthetic Shoko Yamahata Letton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE EIKO AND KOMA: DANCE PHILOSOPHY AND AESTHETIC By SHOKO YAMAHATA LETTON A Thesis submitted to the Department of Dance in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Shoko Yamahata Letton defended on October 18, 2007. ____________________________________ Sally R. Sommer Professor Directing Thesis ____________________________________ Tricia H. Young Committee Member ____________________________________ John O. Perpener III Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________________ Patricia Phillips, Co-Chair, Department of Dance ___________________________________________ Russell Sandifer, Co-Chair, Department of Dance ___________________________________________ Sally E. McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii Dedicated to all the people who love Eiko and Koma. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been completed without the following people. I thank Eiko and Koma for my life-changing experiences, access to all the resources they have, interviews, wonderful conversations and delicious meals. I appreciate Dr. Sally Sommer’s enormous assistance, encouragement and advice when finishing this thesis. I sincerely respect her vast knowledge in dance and her careful and strict editing which comes from her career as dance critic, and, her wonderful personality. Dr. William Sommer’s kindness and hospitality also allowed me to work extensively with his wife. -

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein The University’s early, ardent, and exceptional support for the arts may be showing signs of a renaissance. If you drive onto the Brandeis campus humanities, social sciences, and in late March or April, you will see natural sciences. Brandeis’s brightly colored banners along the “significant deviation” was to add a peripheral road. Their white squiggle fourth area to its core: music, theater denotes the Creative Arts Festival, 10 arts, fine arts. The School of Music, days full of drama, comedy, dance, art Drama, and Fine Arts opened in 1949 exhibitions, poetry readings, and with one teacher, Erwin Bodky, a music, organized with blessed musician and an authority on Bach’s persistence by Elaine Wong, associate keyboard works. By 1952, several Leonard dean of arts and sciences. Most of the pioneering faculty had joined the Leonard Bernstein, 1952 work is by students, but some staff and School of Creative Arts, as it came to faculty also participate, as well as a be known, and concentrations were few outside artists: an expert in East available in the three areas. All Asian calligraphy running a workshop, students, however, were required to for example, or performances from take some creative arts and according MOMIX, a professional dance troupe. to Sachar, “we were one of the few The Wish-Water Cycle, brainchild of colleges to include this area in its Robin Dash, visiting scholar/artist in requirements. In most established the Humanities Interdisciplinary universities, the arts were still Program, transforms the Volen Plaza struggling to attain respectability as an into a rainbow of participants’ wishes academic discipline.” floating in bowls of colored water: “I wish poverty was a thing of the past,” But at newly founded Brandeis, the “wooden spoons and close friends for arts were central to its mission. -

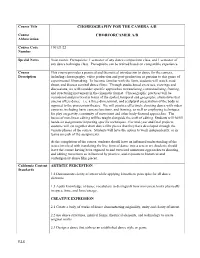

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

SCAN | Journal of Media Arts Culture

:: SCAN | journal of media arts culture :: Scan Journal vol 2 number 3 december 2005 Lost City Found: an interview with Luc Sante Peter Doyle Luc Sante’s books Low life: Lures and Snares of Old New York (1991) and Evidence (1992) both helped produce and partook of a much broader awakening of interest in hitherto neglected cultural histories of cities of the New World. In lucid, imaginative but unforced prose, Low life maps the simultaneously familiar and wildly exotic undercultures of late nineteenth century New York - the grifters, drifters, dopers, prostitutes, orphans, con men, gangsters, sexual adventurers, bohemians and eccentrics, and the tenements, alleys, saloons, clubs, brothels and tea pads they inhabited. Evidence revisits that physical territory via a series of NYPD homicide photographs from the early twentieth century. Rigorously considered, yet expressed in clear poetic prose, Evidence offers subtle textual meditations on the photograph at large and the forensic photograph in particular. These two works, with their keen attention to the fabric of the everyday, and their broader sympathies for fringe and outsider cultures have significantly contributed to an awakening of interest in cultural histories of New York and of cities in general. Sante’s Factory of Facts (1998) weaves personal memoir, family memoir and broad ‘ethno-history’ into a meditation on language, cultural ancestry and selfhood. Sante has written regularly for The New York Review of Books since the 1980s, in which appeared his important essay ‘My Lost City’ (That essay has been more recently anthologised in Best American Essays 2004). This interview was conducted via email in the aftermath of Sante’s visit to Sydney in late 2004, during which he delivered a keynote address at Macquarie University Media Department’s Ghost Town Seminar. -

Pieces 1990 - 2005 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KILL ALL YOUR DARLINGS: PIECES 1990 - 2005 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Luc Sante,Greil Marcus | 304 pages | 18 Oct 2007 | Puncture Publications | 9781891241536 | English | Portland, United States Kill All Your Darlings: Pieces 1990 - 2005 PDF Book Added to Watchlist. Call us on or send us an email at. Jan 23, David rated it really liked it Shelves: anthologies-and-collections , read-in , unexpectedly-terrific. If he were in my arts weekly, I'd read him every week and it probably wouldn't change my consumption patterns at all. My thoughts on why Luc Sante is annoying TK. If I pitched you a story about the Beat generation led by Harry Potter, the new Harry Osborne, a guy from X-Men and the guy from Boardwalk Empire with half his face missing, I'm sure the reaction would be pretty great. Would like to read his other book, Low Life. May 20, Paul Bryant rated it liked it Shelves: autobiography-memoir. Permissions Librarian Erin Darke Apr 01, Valentine Valentino rated it really liked it. View 2 comments. Kill Your Darlings repeats the initial reaction to Carr's response to Ginsberg's complicated life, "Perfect. Color: Color. If this item isn't available to be reserved nearby, add the item to your basket instead and select 'Deliver to my local shop' at the checkout, to be able to collect it from there at a later date. When he's on which is most of the time here , he creates vivid images and ideas that perfectly describe what he's talking about -- whether it be New York, the invention of the blues, Bob Dylan, or visual art. -

David Gordon

David Gordon - ‘80s ARCHIVEOGRAPHY - Part 2 1 #1 DAVID IS SURPRISED - IN 1982 - when - ç BONNIE BROOKS - PROGRAM SPECIALIST AT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS - - volunteers to leave her secure government job - and to relocate - from Washington DC to NYC - to become - Managing Director of the newly incorporated Pick Up Performance Company. #2 DAVID IS SURPRISED - to use metal folding chairs - for the 1st time - since 1974/75 - in a new work called T.V. Reel - to be performed in the Setterfield/Gordon studio - and - David asks artist - ç POWER BOOTHE - who designed everything in Trying Times - 1982 - to repaint old painted plaster studio walls - for the performance - to look like - new unpainted taped sheet rock studio walls - and surprised when Power agrees. It’s a good visual joke - David says - and cheaper - than to paint ê new taped unpainted sheet rock - 2 coatsa white. #1 David buys new çchairs - for new T.V. Reel - with 2 bars - far apart enough - to do original ‘74 Chair moves #2 Step up on - metal chairs - and - stand up n’step up - and stand up. With no bars - legs spread - and spread. #1 Original metal chairs - borrowed from Lucinda Childs - (see ‘70s ARCHIVEOGRAPHY - Part 2) have bars - between front’n front legs - and back’n back legs. #2 Company is Appalachian? Adirondack? Some kinda mountain. #1 Borrowed Lucinda Childs’ chairs - are blue. New chairs are brown. We still have original blue chairs - David says. David Gordon - ‘80s ARCHIVEOGRAPHY - Part 2 2 #2 1982 - T.V. Reel is performed by Valda Setterfield, Nina Martin î Keith Marshall, Paul Thompson, Susan Eschelbach, David Gordon and Margaret Hoeffel - danced to looped excerpts of - Miller’s Reel recorded in 1976 - by New England Conservatory country fiddle band - and conducted by Gunther Schuller. -

Embodied History in Ralph Lemon's Come Home Charley Patton

“My Body as a Memory Map:” Embodied History in Ralph Lemon’s Come Home Charley Patton Doria E. Charlson I begin with the body, no way around it. The body as place, memory, culture, and as a vehicle for a cultural language. And so of course I’m in a current state of the wonderment of the politics of form. That I can feel both emotional outrageousness with my body as a memory map, an emotional geography of a particular American identity...1 Choreographer and visual artist Ralph Lemon’s interventions into the themes of race, art, identity, and history are a hallmark of his almost four-decade- long career as a performer and art-maker. Lemon, a native of Minnesota, was a student of dance and theater who began his career in New York, performing with multimedia artists such as Meredith Monk before starting his own company in 1985. Lemon’s artistic style is intermedial and draws on the visual, aural, musical, and physical to explore themes related to his personal history. Geography, Lemon’s trilogy of dance and intermedial artistic pieces, spans ten years of global, investigative creative processes aimed at unearthing the relationships among—and the possible representations of—race, art, identity, and history. Part one of the trilogy, also called Geography, premiered in 1997 as a dance piece and was inspired by Lemon’s journey to Africa, in particular to Côte d'Ivoire and Guinea, where Lemon sought to more deeply understand his identity as an African-American male artist. He subseQuently published a collection of writings, drawings, and notes which he had amassed during his research and travel in Africa under the title Geography: Art, Race, Exile.