Download PDF 3.01 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, wfiMe others may be from any type of computer printer. Tfie quality of this reproducthm Is dependent upon ttie quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, ootored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleodthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wiU be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to t>e removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at ttie upper left-tiand comer and continuing from left to rigtit in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have t>een reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higtier qualify 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any pfiotographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional ctiarge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMT CHILDREN'S DANCE: AN EXPLORATION THROUGH THE TECHNIQUES OF MERGE CUNNINGHAM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sharon L. Unrau, M.A., CM.A. The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Emeritus Philip Clark Professor Seymour Kleinman, Advisor Assistant Professor Fiona Travis UMI Number 9962456 Copyright 2000 by Unrau, Sharon Lynn All rights reserved. -

University of California, Irvine an Exploration Into

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE AN EXPLORATION INTO DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY AND APPLICATIONS FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF DANCE EDUCATION THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS In Dance by Carl D. Sanders, Jr. Thesis Committee: Professor Lisa Naugle, PhD, Chair Professor Mary Corey Professor Alan Terricciano 2021 ©2021 Carl D. Sanders, Jr. DEDICATION To My supportive wife Mariana Sanders My loyal alebrijes Koda-Bella-Zen My loving mother Faye and father Carl Sanders My encouraging sister Shawana Sanders-Swain My spiritual brothers Dr. Ras Mikey C., Marc Spaulding, and Marshall King Those who have contributed to my life experiences, shaping my artistry. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS v INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Review of Literature Digital Literacy in Dance 5 CHAPTER 2: Methods Dance Education and Autonomous Exploration 15 CHAPTER 3: Findings Robotics for Dancers 23 CONCLUSION 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 31 APPENDIX: Project Video-Link Archive 36 Robot Engineering Info. Project Equipment List iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my Master of Fine Arts in Dance Thesis Committee Chair Lisa Naugle for her guidance, inspiration, compassion, intellect, enthusiasm, and trust to take on this research by following my instincts as an artist and guiding me as an emerging scholar. I also thank the committee members Professor Mary Corey and Professor Alan Terricciano for their support, encouragement, and advice throughout my research and academic journey. Thank you to the Claire Trevor School of the Arts Dance Department faculty, without your support this thesis would not have been possible;. -

Wedding Guide Resort Description

WEDDING GUIDE RESORT DESCRIPTION Secrets Bahia Mita Surf & Spa exudes romance and luxury in the exclusive area of Bahia de Banderas, near Punta Mita and Marina Cruz de Huanacaxtle. This adults-only getaway offersUnlimited-Luxury ® privileges, including limitless gourmet dining and top-shelf spirits, daily activities, live entertainment, free wi-fi and more. All 278 spacious suites feature remarkable tropical views or ocean views, modern décor and refined luxury amenities. Relax at the world-class spa by Pevonia®, try out one of the exquisite, gourmet restaurants or just sip a cocktail poolside. Plus, guests can enjoy exclusive free-flow access to Dreams Bahia Mita Surf & Spa next door, with all the added benefits of two resorts in one. Do it all or do nothing at all at this romantic exclusive hideaway. Resort Address More information & Contact us Carretera Cruz de Huanacaxtle – Punta de Mita No. 5 Visit secretsresorts.com/bahia-mita for information about Bahía de Banderas, Bucerías Nayarit the property, rooms, activities and more. 63762 México Email: [email protected] Secrets Resorts & Spas Last updated 04/21 2 WEDDING IN PARADISE PACKAGE FEATURES • Symbolic ceremony* • Wedding organization and personal touch of on-site wedding coordinator • Preparation and ironing of couple’s wedding day attire • Complimentary room for one member of the wedding couple the night before the wedding (based on availability and upon request) • Bouquet(s) and/or boutonniere(s) for wedding couple • Wedding cake and sparkling wine toast (for up -

Takehisa Kosugi – SPACINGS

Ikon Gallery, 1 Oozells Square, Brindleyplace, Birmingham B1 2HS 0121 248 0708 / www.ikon-gallery.org Open Tuesday-Sunday, 11am-5pm / free entry Takehisa Kosugi SPACINGS 22 July – 27 September 2015 Takehisa Kosugi, Solo Concert, 23 September 2008. The Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse. Photographer: Kiyotoshi Takashima. Ikon presents the first major solo exhibition in the UK by Japanese composer and artist Takehisa Kosugi (b 1938). A pioneer of experimental music in Japan in the early 1960s, he is one of the most influential artists of his generation. Closely associated with the Fluxus movement, Kosugi joined the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in the 1970s, becoming Musical Director in 1995, and working with the Company up until its final performance in 2011. This exhibition will feature three sound installations, including one made especially for Ikon. Often comprising everyday materials and radio electronics, they involve interactions with wind, electricity and light, making sonic relationships between objects. Kosugi was first drawn to music by his father’s enthusiasm for playing the harmonica, and recordings of violinists Mischa Elman and Joseph Szigeti, which he heard while growing up in post-war Tokyo. He went on to study musicology at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music during the late 1950s. He was inspired by the spirit of experimentation coming from Europe and the US, while simultaneously intrigued by traditional Japanese music, in particular Noh Theatre, and its concept of ‘ma’ - the conscious appreciation of the in-between-ness of one sound and another. “That sense of ma in traditional Japanese music, the sense of timing is different from Western music. -

Catalogo Leilão GP Bento 2020.Pdf

9° LEILÃO VIRTUAL GP BENTO GONÇALVES Z 11 De Novembro Quarta - Feira - 19:30 horas Z Ante-Véspera do GP Bento Gonçalves Transmissão Internet: www.tvleilao.net / www.agenciatbs.com.br TBS TBS PARANÁ RIO GRANDE DO SUL Henrique Marquez( (41)98740.3301 Mário Márquez ( (51) 98298.8297 [email protected] [email protected] Wagner Lachovitz((41)99605.6499 [email protected] TBS Oriente Medio Aditiyan Selvaratnam ( (968) 9754.2315 [email protected] TBS LEILÃO VIRTUAL GP BENTO GONÇALVES Transmissão ao vivo via Internet: www.tvleilao.net www.agenciatbs.com.br TELEFONES (41) 3023.6466 (51) 99703.5872 (41) 98740.3301 (41) 99605.6499 (41) 99502.0129 (41) 99726.4999 (51) 98298.8297 (51) 97400.6807 TBS SUPER PRÉ-LANCE SÓ O NOSSO PRE-LANCE E MAIORES DÁ PREMIOS DESCONTOS ! PREMIADOTBS O ÚNICO PRÉ-LANCE QUE DÁ PREMIOS ! O PRÉ-LANCE QUE OFERECE OS MAIORES DESCONTOS ! CONCORRA A VIAGENS E PRÊMIOS E GARANTA UM DESCONTO ADICIONAL *Concorrer ao sorteio de 1 viagem de ida e volta para o GP São Paulo 2021* (cada lance gera um cupom numerado e todos participam do sorteio, pelo 1º prêmio da extração da Loteria Federal). ÚLTIMO LANCE DO PRÉ-LANCE = concorre com 10 números PENÚLTIMO LANCE DO PRÉ-LANCE = concorre com 05 números TODOS OS DEMAIS LANCES = concorrem com 01 número *se o ganhador for de SP a viagem valerá para o GP Paraná, em Curitiba. *Concorrer ao sorteio de 1 cronômetro (cada lance gera um cupom numerado e todos participam do sorteio, pelo 2º prêmio da extração da Loteria Federal). -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

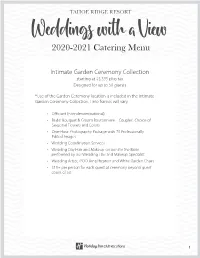

2020-2021 Catering Menu

TAHOE RIDGE RESORT Weddings with a View 2020-2021 Catering Menu Intimate Garden Ceremony Collection starting at $3,395 plus tax Designed for up to 50 guests *Use of the Garden Ceremony location is included in the Intimate Garden Ceremony Collection. Time frames will vary. • Officiant (non-denominational) • Bridal Bouquet & Groom Boutonniere – Couples’ Choice of Seasonal Flowers and Colors • One-Hour Photography Package with 75 Professionally Edited Images • Wedding Coordination Services • Wedding Day Hair and Makeup session for the Bride performed by our Wedding Hair and Makeup Specialist • Wedding Arbor, IPOD Amplification and White Garden Chairs • $10+ per person for each guest at ceremony beyond guest count of 50 1 TAHOE RIDGE RESORT Weddings with a View 2020-2021 Catering Menu Simple Elegance Collection $4,895 plus tax Designed for up to 20 to 30 guests For those who are looking for a simple ceremony and intimate reception to follow. • Officiant (non-denominational) • Bridal Bouquet and Groom Boutonniere, Maid of Honor Bouquet and Best Man Boutonniere, One Bridesmaid’s Bouquet, One Groomsmen’s Boutonniere, Arbor Floral Spray for Ceremony, 3 Hanging Vases to hang from Ceremony Chairs then move to Reception Tables as the Centerpieces • One-Hour Photography Package with 75 Professionally Edited Images • IPOD Amplification • Wedding Day Hair and Makeup session for the Bride performed by our Wedding Hair and Makeup Specialist • Wedding Coordination Services • Couples” Choice of a Custom Wedding Cake or a Mini Dessert Bar with choice of -

Securing Our Dance Heritage: Issues in the Documentation and Preservation of Dance by Catherine J

Securing Our Dance Heritage: Issues in the Documentation and Preservation of Dance by Catherine J. Johnson and Allegra Fuller Snyder July 1999 Council on Library and Information Resources Washington, D.C. ii About the Contributors Catherine Johnson served as director for the Dance Heritage Coalition’s Access to Resources for the History of Dance in Seven Repositories Project. She holds an M.S. in library science from Columbia University with a specialization in rare books and manuscripts and a B.A. from Bethany College with a major in English literature and theater. Ms. Johnson served as the founding director of the Dance Heritage Coalition from 1992 to 1997. Before that, she was assistant curator at the Harvard Theatre Collection, where she was responsible for access, processing, and exhibitions, among other duties. She has held positions at The New York Public Library and the Folger Shakespeare Library. Allegra Fuller Snyder, the American Dance Guild’s 1992 Honoree of the Year, is professor emeritus of dance and former director of the Graduate Program in Dance Ethnology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She has also served as chair of the faculty, School of the Arts, and chair of the Department of Dance at UCLA. She was visiting professor of performance studies at New York University and honorary visiting professor at the University of Surrey, Guildford, England. She has written extensively and directed several films about dance and has received grants from NEA and NEH in addition to numerous honors. Since 1993, she has served as executive director, president, and chairwoman of the board of directors of the Buckminster Fuller Institute. -

Volume 14 2018-2019

Dialogues @ RU Vol. 14 EDITORIAL BOARD FALL 2018 SPRING 2019 Abby Baker Ashley Abrams Natalie Brennan Kelly Allen Hope Dormer Jeannee Auguste Hanna Graifman Jasmine Basuel Katherine Hill Olivia Dineen Taylor Moreau Stephanie Felty Terese Osborne Alec Ferrigno Julianna Rossano Sophia Higgins Katharine Steely-Brown Lindsey Ipson Jennifer Territo Aniza Jahangir Tiffany Yang Esther Leaming Grace Lee Samuel Leibowitz-Lord EDITORS Wyonia McLaurin Tracy Budd Jordan Meyers Lynda Dexheimer Drew Mount Alyson Sandler Erin Telesford COVER DESIGN & Morgan Ulrich TYPESETTING Mike Barbetta © Copyright 2020 by Dialogues@RU All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. ii. CONTENTS Foreword • v Qurratul Akbar, Episode IV: A New Home • 1 Marianna Allen, Saving Dance • 14 Juwairia Ansari, Identity Displacement: How Psychological and Social Factors Intertwine to Impact Refugee Identity • 26 Benjamin Barnett, The Soggy Apple – Misaligned Incentives in NYC Climate Change Protection • 37 Emma Barr, Hearing ≠ Listening: Reconciliation of Hearing and Deaf Cultures • 49 Kenneth Basco, Pokémon Go Dissociate: Cognitive Dissonance in the Mind-Body Relationship in Virtual and Physical Representations of AR Games • 63 Jensen Benko, Constructing Diverse Queer Identity Through Writing Fan Fiction • 73 Simran Bhatia, Modern Maps and Their Detrimental Effects on Politics, Culture, and Behavior • 83 Maya Bryant, The Gentrification of Harlem • 98 Emily Carlos, Autistic Expression: Technology and Its Role in Identity Construction • 108 Eliot Choe, Modern Day Eyes on the Street • 122 Kajal Desai, The Identity Construction of the Black Female Performer in Hip Hop • 134 Mohammed Farooqui, Segregation in New York City Education: Why a Colorblind System is not really “Colorblind” • 148 Stephanie Felty, Reading Versus Watching: Narrative Fiction Consumption and Theory of Mind • 163 iii. -

David Gordon

David Gordon - ‘80s ARCHIVEOGRAPHY - Part 2 1 #1 DAVID IS SURPRISED - IN 1982 - when - ç BONNIE BROOKS - PROGRAM SPECIALIST AT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS - - volunteers to leave her secure government job - and to relocate - from Washington DC to NYC - to become - Managing Director of the newly incorporated Pick Up Performance Company. #2 DAVID IS SURPRISED - to use metal folding chairs - for the 1st time - since 1974/75 - in a new work called T.V. Reel - to be performed in the Setterfield/Gordon studio - and - David asks artist - ç POWER BOOTHE - who designed everything in Trying Times - 1982 - to repaint old painted plaster studio walls - for the performance - to look like - new unpainted taped sheet rock studio walls - and surprised when Power agrees. It’s a good visual joke - David says - and cheaper - than to paint ê new taped unpainted sheet rock - 2 coatsa white. #1 David buys new çchairs - for new T.V. Reel - with 2 bars - far apart enough - to do original ‘74 Chair moves #2 Step up on - metal chairs - and - stand up n’step up - and stand up. With no bars - legs spread - and spread. #1 Original metal chairs - borrowed from Lucinda Childs - (see ‘70s ARCHIVEOGRAPHY - Part 2) have bars - between front’n front legs - and back’n back legs. #2 Company is Appalachian? Adirondack? Some kinda mountain. #1 Borrowed Lucinda Childs’ chairs - are blue. New chairs are brown. We still have original blue chairs - David says. David Gordon - ‘80s ARCHIVEOGRAPHY - Part 2 2 #2 1982 - T.V. Reel is performed by Valda Setterfield, Nina Martin î Keith Marshall, Paul Thompson, Susan Eschelbach, David Gordon and Margaret Hoeffel - danced to looped excerpts of - Miller’s Reel recorded in 1976 - by New England Conservatory country fiddle band - and conducted by Gunther Schuller. -

Checklist of the Exhibition

Checklist of the Exhibition Silverman numbers. The numbering system for works in the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection is explained in Fluxus Codex, edited by Jon Hendricks (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), p. 29.ln the present checklist, the Silverman number appears at the end of each item. Dates: Dating of Fluxus works is an inexact science. The system used here employs two, and sometimes three, dates for each work. The first is the probable date the work was initially produced, or when production of the work began. based on information compiled in Fluxus Codex. If it is known that initial production took a specific period, then a second date, following a dash, is MoMAExh_1502_MasterChecklist used. A date following a slash is the known or probable date that a particular object was made. Titles. In this list, the established titles of Fluxus works and the titles of publications, events, and concerts are printed in italics. The titles of scores and texts not issued as independent publications appear in quotation marks. The capitalization of the titles of Fluxus newspapers follows the originals. Brackets indicate editorial additions to the information printed on the original publication or object. Facsimiles. This exhibition presents reprints (Milan: Flash Art/King Kong International, n.d.) of the Fluxus newspapers (CATS.14- 16, 19,21,22,26,28,44) so that the public may handle them. and Marian Zazeela Collection of The preliminary program for the Fluxus Gilbert and lila Silverman Fluxus Collective Works and movement). [Edited by George Maciunas. Wiesbaden, West Germany: Collection Documentation of Events Fluxus, ca. -

Tanztheater, Pina Bausch and the Ongoing Influence of Her Legacy

AusArt Journal for Research in Art. 5 (2017), 1, pp. 219-228 ISSN 2340-8510 www.ehu.es/ojs/index.php/ausart e-ISSN 2340-9134 DOI: 10.1387/ausart.17704 UPV/EHU TANZTHEATER, PINA BAUSCH AND THE ONGOING INFLUENCE OF HER LEGACY Oihana Vesga Bujan1 London Contemporary Dance School. Postgraduate Choreography in The Place Introducction Pina Bausch and the Tanztheater Wuppertal have been fundamental in the inter- national establishment of Tanztheater as a new and independent dance genre, and their impact is evident and vibrant in the current contemporary dance scene. To support this statement I will first unfold the history of modern dance in Germany, from Rudolf Laban and the German expressive dance movement of the 1920’s, to the creations of Kurt Jooss and finally the formation of Tanztheater Wuppertal in 1973. I will then study Bausch’s life and work, and reveal the essential and unique characteristics of her style, to ultimately prove the ongoing influence of her legacy, looking at one of the final pieces of the 2013 London based choreographic competition The Place Prize. Keywords: TANZTHEATER; BAUSCH, PINA; CHOREOGRAPHY; THEATER TANZTHEATER, PINA BAUSCH Y LA INFLUENCIA ININTERRUMPIDA DE SU LEGADO Resumen Pina Bausch y ThanztheaterWuppertal han sido fundamentales en la difusión interna- cional del Tanztheater/Danza-Teatro, como un nuevo e independiente genero de danza, con evi- dente y substancial impacto en el actual escenario de la danza contemporánea. Para remarcar dicha importancia, señalo en primer lugar, el recorrido de la danza contemporánea en Alemania, desde Rudolf Laban y el movimiento de danza expresiva alemana de los años 1920; hasta las creaciones de KurtJoos, y finalizo con la creación de TanztheaterWuppertal en 1973.