Report on Species/Country Combinations Selected for Review by the Plants Committee Following Cop16 CITES Project No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Journal of International Affairs Vol. 3, 1-41, 2020 Doi: https://doi.org/10.3126/joia.v3i1.29077 Department of International Relations and Diplomacy Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal North-Western Boundary of Nepal Dwarika Dhungel Jagat Bhusal Narendra Khanal Abstract Following the publication of new political maps by India on 2nd and 8th November 2019, the issues related to the source of Mahakali River and Indian occupation of the Nepali territory east of the river, have, once again, come to the surface. And, the Nepali civil society has come out strongly against the newly published political maps of India, prepared a new map of Nepal, showing the whole of the territory east of Mahakali River (about 400 sq. km) as Nepalese land on the basis of Treaty of Sugauli signed in 1816 by East India Company of Great Britain and Raja of Nepal. An analysis of the maps, so far available, shows that changes have been made in the names of the river and places, and there is cartographic aggression and manipulation by India in relation to Mahakali River and its boundary with Nepal’s northwest. It has also been found that Nepal has published a map in the past showing its international boundary without any basis of the treaties and other historical documents. Analysis clearly shows that the river originating from Limpiyadhura is the Mahakali (called Kalee/Kali River) as per Article 5 of the Sugauli treaty and it forms the international boundary between the two countries. Keywords: Anglo-Nepal War, Sugauli Treaty, Cartographic Aggression, Nepal-India Territorial Disputes 1 Dwarika Dhungel, Jagat Bhusal & Narendra Khanal/North-Western … Vol. -

ARCP Final Report

ARCP Final Report Project Reference Number: ARCP2015-13CMY-Zhou Assessment of Climate-Induced Long-term Water Availability in the Ganges Basin and the Impacts on Energy Security in South Asia The following collaborators worked on this project: 1. Dr. Xin Zhou, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan, [email protected] 2. Dr. Bijon Kumer Mitra, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan, [email protected] 3. Dr. Devesh Sharma, Central University of Rajasthan (CURAJ), India, [email protected] 4. Prof. G.M. Tarekul Islam, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), Bangladesh, [email protected] 5. Dr. Rabin Malla, Center of Research for Environment, Energy and Water (CREEW), Nepal, [email protected] 6. Dr. Diego Silva Herran, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan, [email protected] 7. Dr. Brian Johnson, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan, [email protected] Insert Insert Insert other other other logo logo logo Copyright © 2015 Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research APN seeks to maximise discoverability and use of its knowledge and information. All publications are made available through its online repository “APN E-Lib” (www.apn-gcr.org/resources/). Unless otherwise indicated, APN publications may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services. Appropriate acknowledgement of APN as the source and copyright holder must be given, while APN’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services must not be implied in any way. For reuse requests: http://www.apn-gcr.org/?p=10807 Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................i Project Overview ..................................................................................................................... -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

Antimycobacterial Activity of the Ethanolic Extract of the Wood of Bulnesia Sarmientoi Lorentz Ex

ANTIMYCOBACTERIAL ACTIVITY OF THE ETHANOLIC EXTRACT OF THE WOOD OF BULNESIA SARMIENTOI LORENTZ EX. GRISEB MICKEL R. HIEBERT,A MARÍA EUGENIA FLORES-GIUBI,A JAVIER E. BARUA,A GLORIA M. MOLINA-SALINAS,B ESTEBAN A. FERRO,A NELSON L. ALVARENGAA* (Received June 2012; Accepted August 2012) ABSTRACT In this work the in vitro antimycobacterial activity of the ethanolic extract obtained from the wood of Bulnesia sarmientoi Lorentz ex. Griseb and its chemical compo- sition were studied. The preliminary phytochemical analysis of the extract showed the presence of steroids and/or triterpenes and tannins, and a GC/MS fingerprint analysis identified guaiol and bulnesol as main volatile components of the extract, based on their retention index and the comparison of their mass spectra with those contained in NIST libraries. The extract showed activity against Mycobacterium tu- berculosis H37Rv strain with a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 50 µg/mL, using the microplate Alamar Blue assay. These results suggest that the extract could be a source of antimicrobial substances against M. tuberculosis. www.relaquim.com Keywords: Bulnesia sarmientoi, antimycobacterial, Alamar Blue, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, GC/MS. RESUMEN En el presente trabajo se evaluó la actividad antimicobacteriana in vitro y se estudió la composición química del extracto etanólico obtenido de la madera de Bulnesia sarmientoi Lorentz ex. Griseb. El estudio fitoquímico preliminar mostró la presen- cia de taninos y esteroides y/o triterpenos. Los componentes volátiles del extracto fueron además analizados por cromatografía gaseosa acoplada a espectrometría de masas (CG/EM) e identificados por comparación con las librerías NIST 21 y 107 del equipo y además con base en sus índices de retención. -

Toskar Newsletter

TOSKAR NEWSLETTER A Quarterly Newsletter of the Orchid Society of Karnataka (TOSKAR) Vol. No. 4; Issue: ii; 2017 THE ORCHID SOCIETY OF KARNATAKA www.toskar.org ● [email protected] From the Editor’s Desk TOSKAR NEWSLETTER 21st June 2017 The much-awaited monsoon has set in and it is a sight to see EDITORIAL BOARD shiny green and happy leaves and waiting to put forth their best (Vide Circular No. TOSKAR/2016 Dated 20th May 2016) growth and amazing flowers. Orchids in tropics love the monsoon weather and respond with a luxurious growth and it is also time for us (hobbyists) to ensure that our orchids are fed well so that Chairman plants put up good vegetative growth. But do take care of your Dr. Sadananda Hegde plants especially if you are growing them in pots and exposed to continuous rains, you may have problems! it is alright for mounted plants. In addition, all of us have faced problems with Members snails and slugs, watch out for these as they could be devastating. Mr. S. G. Ramakumar Take adequate precautions with regard to onset of fungal and Mr. Sriram Kumar bacterial diseases as the moisture and warmth is ideal for their multiplication. This is also time for division or for propagation if Editor the plants have flowered. Dr. K. S. Shashidhar Many of our members are growing some wonderful species and hybrids in Bangalore conditions and their apt care and culture is Associate Editor seen by the fantastic blooms. Here I always wanted some of them Mr. Ravee Bhat to share their finer points or tips for care with other growers. -

Review of Species Selected from the Analysis of 2004 EC Annual Report

Review of species selected from the Analysis of 2005 EC Annual Report to CITES (Version edited for public release) Prepared for the European Commission Directorate General E - Environment ENV.E.2. – Development and Environment by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre May, 2008 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK ABOUT UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the world‘s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision- makers recognize the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre‘s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP, the European Commission or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Changes to CITES Species Listings

NOTICE TO THE WILDLIFE IMPORT/EXPORT COMMUNITY December 21, 2016 Subject: Changes to CITES Species Listings Background: Party countries of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) meet approximately every two years for a Conference of the Parties. During these meetings, countries review and vote on amendments to the listings of protected species in CITES Appendix I and Appendix II. Such amendments become effective 90 days after the last day of the meeting unless Party countries agree to delay implementation. The most recent Conference of the Parties (CoP 17) was held in Johannesburg, South Africa, September 24 – October 4, 2016. Action: Except as noted below, the amendments to CITES Appendices I and II that were adopted at CoP 17, will be effective on January 2, 2017. Any specimens of these species imported into, or exported from, the United States on or after January 2, 2017 will require CITES documentation as specified under the amended listings. The import, export, or re-export of shipments of these species that are accompanied by CITES documents reflecting a pre-January 2 listing status or that lack CITES documents because no listing was previously in effect must be completed by midnight (local time at the point of import/export) on January 1, 2017. Importers and exporters can find the official revised CITES appendices on the CITES website. Species Added to Appendix I . Abronia anzuetoi (Alligator lizard) . Abronia campbelli (Alligator lizard) . Abronia fimbriata (Alligator lizard) . Abronia frosti (Alligator lizard) . Abronia meledona (Alligator lizard) . Cnemaspis psychedelica (Psychedelic rock gecko) . Lygodactylus williamsi (Turquoise dwarf gecko) . Telmatobius coleus (Titicaca water frog) . -

Diversity and Distribution of Vascular Epiphytic Flora in Sub-Temperate Forests of Darjeeling Himalaya, India

Annual Research & Review in Biology 35(5): 63-81, 2020; Article no.ARRB.57913 ISSN: 2347-565X, NLM ID: 101632869 Diversity and Distribution of Vascular Epiphytic Flora in Sub-temperate Forests of Darjeeling Himalaya, India Preshina Rai1 and Saurav Moktan1* 1Department of Botany, University of Calcutta, 35, B.C. Road, Kolkata, 700 019, West Bengal, India. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Author PR conducted field study, collected data and prepared initial draft including literature searches. Author SM provided taxonomic expertise with identification and data analysis. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARRB/2020/v35i530226 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Rishee K. Kalaria, Navsari Agricultural University, India. Reviewers: (1) Sameh Cherif, University of Carthage, Tunisia. (2) Ricardo Moreno-González, University of Göttingen, Germany. (3) Nelson Túlio Lage Pena, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Brazil. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/57913 Received 06 April 2020 Accepted 11 June 2020 Original Research Article Published 22 June 2020 ABSTRACT Aims: This communication deals with the diversity and distribution including host species distribution of vascular epiphytes also reflecting its phenological observations. Study Design: Random field survey was carried out in the study site to identify and record the taxa. Host species was identified and vascular epiphytes were noted. Study Site and Duration: The study was conducted in the sub-temperate forests of Darjeeling Himalaya which is a part of the eastern Himalaya hotspot. The zone extends between 1200 to 1850 m amsl representing the amalgamation of both sub-tropical and temperate vegetation. -

Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants As Sources of Therapeutic Agents: Their Ethnopharmacological Uses, Chemical Composition, and Biological Activities

biomolecules Review Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants as Sources of Therapeutic Agents: Their Ethnopharmacological Uses, Chemical Composition, and Biological Activities Ari Satia Nugraha 1,* , Bawon Triatmoko 1 , Phurpa Wangchuk 2 and Paul A. Keller 3,* 1 Drug Utilisation and Discovery Research Group, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Jember, Jember, Jawa Timur 68121, Indonesia; [email protected] 2 Centre for Biodiscovery and Molecular Development of Therapeutics, Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD 4878, Australia; [email protected] 3 School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience and Molecular Horizons, University of Wollongong, and Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, NSW 2522 Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.S.N.); [email protected] (P.A.K.); Tel.: +62-3-3132-4736 (A.S.N.); +61-2-4221-4692 (P.A.K.) Received: 17 December 2019; Accepted: 21 January 2020; Published: 24 January 2020 Abstract: This is an extensive review on epiphytic plants that have been used traditionally as medicines. It provides information on 185 epiphytes and their traditional medicinal uses, regions where Indigenous people use the plants, parts of the plants used as medicines and their preparation, and their reported phytochemical properties and pharmacological properties aligned with their traditional uses. These epiphytic medicinal plants are able to produce a range of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, and a total of 842 phytochemicals have been identified to date. As many as 71 epiphytic medicinal plants were studied for their biological activities, showing promising pharmacological activities, including as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer agents. There are several species that were not investigated for their activities and are worthy of exploration. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

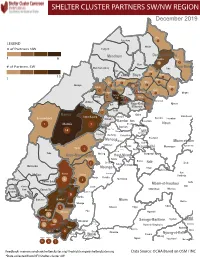

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W.