18-701 Petition for Rehearing.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

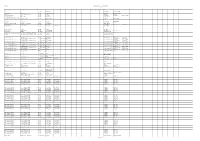

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Lee Daniels on Empire: the Show Has Already Changed Homophobes' Minds

8/15/2018 Empire on Fox: Lee Daniels on his Show's Effect on Homophobia | Time Lee Daniels on Empire: The Show Has Already Changed Homophobes' Minds Lee Daniels on Dec. 1, 2014 in New York City. Theo Warg—Getty Images / IFP By LILY ROTHMAN January 7, 2015 Lee Daniels is best known as the lmmaker behind gritty independent lms like Precious, but his new project is the slick primetime drama Empire, premiering Jan. 7 on Fox, which he co-created with Danny Strong. Daniels recently spoke to TIME about the show, and how — despite not being independently made — http://time.com/3656583/lee-daniels-empire/ 1/3 8/15/2018 Empire on Fox: Lee Daniels on his Show's Effect on Homophobia | Time it’s a personal story. The Shakespeare-inected tale of record mogul Lucious Lyon (Terrence Howard), his ex-wife Cookie (Taraji P. Henson) and their sons Andre, Jamal and Hakeem, often draws on stories from his own life. And, he tells TIME, the show is already making a difference toward his larger aim of increasing tolerance among its audience: TIME: You’ve told a story about trying on your mother’s shoes as a child. There’s a scene in the Empire pilot that sounds very similar to that episode, where Lucious reacts to seeing his young son do just that… Lee Daniels: I was terried of that scene. My sister was an extra — she’s in the scene — and when the kid put the shoes on, having him walk in front of his father, I had a meltdown. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem

ENTERTAINMENT ‘Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem By Ericka Blount Danois on September 9, 2013 “One looks down in secret and sees many things,” Dr. Valentin Narcisse (Jeffrey Wright) deadpans, speaking to Chalky White (Michael K. Williams). “You know what I saw? A servant trying to be a king.” And so begins a dance of power, politics and personality between two of the most electrifying, enigmatic actors on the television screen today. Each time the two are on screen—together or apart—they breathed new life into tonight’s premiere episode of Boardwalk Empire season four, with dark humor, slight smiles, powerful glances, smart clothes and killer lines. Entitled “New York Sour,” the episode opened with bombast, unlike the slow boil of previous seasons. Set in 1924, we’re introduced to the tasteful opulence of Chalky White’s new club, The Onyx, decorated with sconces custom-made in Paris and shimmering, shapely dancing girls. Chalky earned an ally, and eventually a partnership to be able to open the club, with former political boss and gangster Nucky Thompson (Steve Buscemi) by saving Nucky’s life last season. This sister club to the legendary Cotton Club in Harlem is Whites-only, but features Black acts. There are some cringe-worthy moments when Chalky, normally proud and infallible, has to deal with racism and bends over to appease his White clientele. But more often, Chalky—a Texas- born force to be reckoned with—breathes an insistent dose of much needed humor into what sometimes devolves into cheap shoot ’em up thrills this season. The meeting of the minds between Narcisse and Chalky takes root in the aftermath of a mistake by Chalky’s right hand man, Dunn Purnsley (Erik LaRay Harvey), who engages in an illicit interracial tryst that turns out to be a dramatic, racially-charged sex game gone horribly wrong. -

Soap Alum Claims Lee Daniels Stole Empire Idea from Him by Kambra Clifford Posted Tuesday, January 19, 2016 12:52:29 PM

Soap alum claims Lee Daniels stole Empire idea from him by Kambra Clifford Posted Tuesday, January 19, 2016 12:52:29 PM Share this story AddThis Sharing 00 Share to Google BookmarkShare to FacebookShare to TwitterShare to PrintShare to EmailShare to More SHARES Another World alum Clayton Prince (ex-Reuben Lawrence) is making headlines with the claim that the idea for Empire originally belonged to him -- and Lee Daniels allegedly stole it. Some super soapy drama has hit the entertainment world this week. Former Another World star Clayton Prince (ex-Reuben Lawrence) has filed a lawsuit against Empire producer Lee Daniels that alleges the premise for Fox's successful primetime dramas was actually his idea and that Daniels stole it. Prince, who's legal name is Clayton Prince Tanksley, filed the suit in federal court on Friday, also naming Empire co-creator Danny Strong, Fox, and the Greater Philadelphia Film Office and its executive director, Sharon Pinkenson. "This will be a David vs. Goliath kind of situation, but I want people to know what happened," Prince says of the lawsuit, which claims Daniels stole the concept for Empire from Prince after he pitched his show to Daniels at the Greater Philadelphia Film Office's 'Philly Pitch' in April 2008. "I want people to know the truth." Prince's attorney, Mary Elizabeth Bogan, has known Prince for eleven years and says she was aware of his show, which he called Cream, years before Empire premiered. "I'm very familiar with Clayton's work and when the Empire promo first came out, my original thought was, 'Clayton must have landed that deal. -

Dossier De Presse TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE

DOSSIER DE PRESSE TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE DÉCOUVRIR LES PREMIÈRES IMAGES DE LA SAISON 1 SUCCESS STORY : Série dramatique n°1 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA Série n°2 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA, derrière Big Bang Theory sur CBS Meilleur score pour une nouvelle série aux USA depuis Desperate Housewives et Grey’s Anatomy en 2004-2005 Plus forte progression durant une première saison (+65%) depuis Docteur House en 2004 Série la plus tweetée avec 627 369 live tweets par épisode (devant The Walking Dead) SYNOPSIS Lucious Lyon (Terrence Howard, nominé aux lorsque son ex-femme, Cookie (Taraji P. Henson, Oscars et aux Golden Globes pour Hustle & nominée aux Oscars et aux Emmy Awards, Flow) est le roi du hip-hop. Ancien petit voyou, L’étrange histoire de Benjamin Button, Person son talent lui a permis de devenir un artiste of Interest), revient sept ans plus tôt que prévu, talentueux mais surtout le président d’Empire après presque 20 ans de détention. Audacieuse Entertainment. Pendant des années, son et sans scrupule, Cookie considère qu’elle s’est règne a été sans partage. Mais tout bascule sacrifiée pour que Lucious puisse démarrer sa lorsqu’il apprend qu’il est atteint d’une maladie carrière puis bâtir un empire, en vendant de la dégénérative. Il est désormais contraint de drogue. Trafic pour lequel elle a été envoyée transmettre à ses trois fils les clefs de son en prison. empire, sans faire éclater la cellule familiale déjà fragile. Pour le moment, Lucious reste à la tête d’Empire Entertainment. -

Media Analysis.Docx

Surname 1 Student’s Name Professor’s Name Course Date Media Analysis The first season of Empire drama series was premiered on Fox on January 7, 2015, and till March 18, 2015. The show was aired on Fox on Wednesdays at 9.00 PM ET (Fox, 2015). The 12 episodes American Television series, centers on an entertainment company, The Empire Entertainment Company. It is a family business making lots of profit from signing in popular musicians and hip-hop artists as well as recordings from talented family members. Each of the family members fights for control over the company. The main casts in the movie are a divorced couple Lucious Lyon and his ex-wife Cookie Lyon. The couple has three sons Andre (oldest son and married to Rhonda), Jamal (middle son), and Hakeem Lyon (Fox, 2015). Lucious and Cookie spent most of their early lives in drug dealing until Cookie was imprisoned. Although the family was living in poverty, they had ambitions to prosper in the music industry. They were a happy family always protecting and encouraging each other until Cookie was imprisoned (Fox, 2015). The interaction in the Empire Series is family-based. The ambitions and fight for control over The Empire Company bring the interactions in the family (IMDb, 2015). While in jail, the interaction between Cookie, Lucious, and their sons are minimal. After the release of Cookie from jail, her relationship with her ex-husband Lucious is business-centered until episode 7, where it becomes intimate (Fox, 2015). Although the divorced couple tries to keep their relationshipx-essays.com business-wise, it is clear Lucious loves Cookie. -

Empire Post Media (EMPM) Commencing at 9:30 A.M

U.S. SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Release No. 92745 / August 24, 2021 The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission announced the temporary suspension of trading in the securities of Empire Post Media (EMPM) commencing at 9:30 a.m. EDT on August 25, 2021 and terminating at 11:59 p.m. EDT on September 8, 2021. The Commission temporarily suspended trading in the securities of the foregoing company due to a lack of current and accurate information about the company because it has not filed certain periodic reports with the Commission. This order was entered pursuant to Section 12(k) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Exchange Act). The Commission cautions brokers, dealers, shareholders and prospective purchasers that they should carefully consider the foregoing information along with all other currently available information and any information subsequently issued by this company. Brokers and dealers should be alert to the fact that, pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 15c2-11, at the termination of the trading suspension, no quotation may be entered relating to the securities of the subject company unless and until the broker or dealer has strictly complied with all of the provisions of the rule. If any broker or dealer is uncertain as to what is required by the rule, it should refrain from entering quotations relating to the securities of this company that has been subject to the trading suspension until such time as it has familiarized itself with the rule and is certain that all of its provisions have been met. -

EMPIRE and Comfort Systems OWNER’S MANUAL

INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS EMPIRE AND Comfort Systems OWNER’S MANUAL DIRECT VENT Direct Vent Zero Clearance Gas GAS FIREPLACE HEATER Fireplace Heater MODEL SERIES MILLIVOLT STANDING PILOT DVP42DP31(N,P)-2 DIRECT IGNITION DVP42DP51N-1 INTERMITTENT PILOT DVP42DP71(N,P)-3 REMOTE RF Installer: Leave this manual with the appliance. DVP42DP91(N,P)-3 Consumer: Retain this manual for future reference. UL FILE NO. MH30033 GAS-FIRED WARNING: If the information in these instruc- tions are not followed exactly, a fire or explosion may result causing property damage, personal in- jury or loss of life. — Do not store or use gasoline or other flammable WARNING: If not installed, operated and maintained vapors and liquids in the vicinity of this or any in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, other appliance. this product could expose you to substances in fuel — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS or from fuel combustion which can cause death or • Do not try to light any appliance. serious illness. • Do not touch any electrical switch; do not use any phone in your building. This appliance may be installed in an aftermarket, • Immediately call your gas supplier from a permanently located, manufactured home (USA only) neighbor’s phone. Follow the gas supplier’s or mobile home, where not prohibited by state or local instructions. codes. • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, call the fire department. This appliance is only for use with the type of gas indicated on the rating plate. This appliance is not — Installation and service must be performed by a convertible for use with other gases, unless a certified qualified installer, service agency or the gas sup- kit is used. -

Scene on Radio American Empire (Season 4, Episode 9) Transcript

Scene on Radio American Empire (Season 4, Episode 9) Transcript http://www.sceneonradio.org/s4-e9-american-empire/ John Biewen: Chenjerai, we are opening a can of worms with this one. We’ve talked a lot about how the U.S. has dealt with democracy on the North American continent. But we really haven’t explored the U.S role in democracy out there in the larger world. Chenjerai Kumanyika: Oh, so you mean like how we’ve brought democracy to other people around the world? John Biewen: Well, we’ve brought something. But, yes, actually I thought we should as part of this series, we should explore an idea that is controversial for a lot of people, and that is the idea of American empire. Chenjerai Kumanyika: Okay, so, what you’re saying is we’re about to start a whole new podcast. Like right now. John Biewen: (Laughs) Exactly. Obviously, it could be at least a twenty part series, but actually, for today, maybe, could we just do one episode? 1 Chenjerai Kumanyika: I think it’s easy actually. America’s not an empire. We’re a force for freedom in the world, and my evidence for this is World War II. And I think we’re done. Thanks for listening. John Biewen: (laughs) Yeah. That does settle it really. Chenjerai Kumanyika: This is one of those areas where I think it’s good to have a podcast actually, because this stuff comes up in my social world, you know, like at dinner parties. Do you remember before COVID when we used to actually have dinner parties? John Biewen: Faint memories of that experience.