The Politics of Civil Rights in the Truman Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Governmentality, and the De-Colonial Politics of the Original Rainbow Coalition of Chicago

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2012-01-01 In The pirS it Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago Antonio R. Lopez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Lopez, Antonio R., "In The pS irit Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago" (2012). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2127. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2127 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERNMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO ANTONIO R. LOPEZ Department of History APPROVED: Yolanda Chávez-Leyva, Ph.D., Chair Ernesto Chávez, Ph.D. Maceo Dailey, Ph.D. John Márquez, Ph.D. Benjamin C. Flores, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Antonio R. López 2012 IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO by ANTONIO R. LOPEZ, B.A., M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO August 2012 Acknowledgements As with all accomplishments that require great expenditures of time, labor, and resources, the completion of this dissertation was assisted by many individuals and institutions. -

History's Future

Winter 2003 ture the multigenera- American and East Asian history, to tional change that name a few. Recent faculty publica- shapes the Los tions span topics from the history of Angeles immigrant household government in America to communities. Down the study of medieval women. the corridor, Philip “The momentum of the history Ethington documents department is being fueled by some the timeless transfor- outstanding new faculty members, a mation of Los Angeles’ growing list of external collaborations people, landscapes and and the smart use of technology,” architecture through says College Dean Joseph Aoun. streaming media and “We are positioned to do some great digital panoramic pho- things in the 21st century.” tos. Meanwhile, medievalist Lisa Tales of the West Bitel—a recent The College boasts a strong con- Guggenheim Fellow— figuration of late 19th- and early collaborates with 20th-century American historians, scholars in European and is a pre-eminent center for libraries in a quest to examining the American West. make archives that At the forefront is University detail women’s first Professor and California State religious communities Librarian Kevin Starr, whose book easily accessible via the series chronicling California history Internet. Another col- and the American dream has gained league, Steven Ross, worldwide popularity. partners with the USC Other historians, such as Sanchez Center for Scholarly and Lon Kurashige, study Latino and Technology to docu- Asian immigration patterns to better ment how film shaped understand how American society has ideas about class and organized and changed through time. power in the 20th cen- Indeed, the College’s prime urban tury. -

An Improbable Venture

AN IMPROBABLE VENTURE A HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO NANCY SCOTT ANDERSON THE UCSD PRESS LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA © 1993 by The Regents of the University of California and Nancy Scott Anderson All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Anderson, Nancy Scott. An improbable venture: a history of the University of California, San Diego/ Nancy Scott Anderson 302 p. (not including index) Includes bibliographical references (p. 263-302) and index 1. University of California, San Diego—History. 2. Universities and colleges—California—San Diego. I. University of California, San Diego LD781.S2A65 1993 93-61345 Text typeset in 10/14 pt. Goudy by Prepress Services, University of California, San Diego. Printed and bound by Graphics and Reproduction Services, University of California, San Diego. Cover designed by the Publications Office of University Communications, University of California, San Diego. CONTENTS Foreword.................................................................................................................i Preface.........................................................................................................................v Introduction: The Model and Its Mechanism ............................................................... 1 Chapter One: Ocean Origins ...................................................................................... 15 Chapter Two: A Cathedral on a Bluff ......................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: -

Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8057gjv No online items Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000 Clay Stalls William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/ © 2012 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Charles Luckman Papers, CSLA-34 1 1908-2000 Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000 Collection number: CSLA-34 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Clay Stalls Date Completed: 2008 Encoded by: Clay Stalls © 2012 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Charles Luckman papers Dates: 1908-2000 Collection number: CSLA-34 Creator: Luckman, Charles Collection Size: 101 archival document boxes; 16 oversize boxes; 2 unboxed scrapbooks, 2 flat files Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: This collection consists of the personal papers of the architect and business leader Charles Luckman (1909-1999). Luckman was president of Pepsodent and Lever Brothers in the 1940s. In the 1950s, with William Pereira, he resumed his architectural career. Luckman eventually developed his own nationally-known firm, responsible for such buildings as the Boston Prudential Center, the Fabulous Forum in Los Angeles, and New York's Madison Square Garden. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. Publication Rights Materials in the Department of Archives and Special Collections may be subject to copyright. -

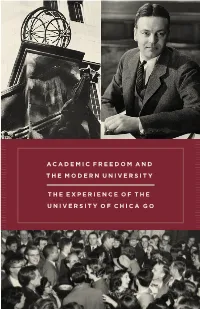

Academic Freedom and the Modern University

— — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And — — — — — — the modern University — — — — — — — — the experience oF the — — — — — — University oF chicA go — — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And the modern University the experience oF the University oF chicA go by john w. boyer 1 academic freedom introdUction his little book on academic freedom at the University of Chicago first appeared fourteen years ago, during a unique moment in our University’s history.1 Given the fundamental importance of freedom of speech to the scholarly mission T of American colleges and universities, I have decided to reissue the book for a new generation of students in the College, as well as for our alumni and parents. I hope it produces a deeper understanding of the challenges that the faculty of the University confronted over many decades in establishing Chicago’s national reputation as a particu- larly steadfast defender of the principle of academic freedom. Broadly understood, academic freedom is a principle that requires us to defend autonomy of thought and expression in our community, manifest in the rights of our students and faculty to speak, write, and teach freely. It is the foundation of the University’s mission to discover, improve, and disseminate knowledge. We do this by raising ideas in a climate of free and rigorous debate, where those ideas will be challenged and refined or discarded, but never stifled or intimidated from expres- sion in the first place. This principle has met regular challenges in our history from forces that have sought to influence our curriculum and research agendas in the name of security, political interests, or financial 1. John W. -

Bonds for Israel Dinner, Chicago, Illinois, May 5, 1968

/ }"- /1, ~ - f'J c_.a_yV.fO~ELEASE Monday M1' s May 6, 1968 OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT • REMARKS OF VICE PRESIDENT HUBERT H. HUMPHREY 20th Anniversary of Israel Celebration Chicago, Illinois May 5, 1968 I salute, with you, the first state in history that was 3500 years old on its 20th birthday. What we recognize tonight is the timeless tradition of mankind's ceaseless search -- no matter what the odds or how long and hard the course -- for freedom of the human spirit and for the dignity and the meaning -- of Man. What we recognize, beyond that, the greatest feat of human invention under divine inspiration and encouragement -- of the 20th or perhaps any other century: The miracle of Israel. It is commonplace to recognize the era we live in as a time of scientific miracles -- of lasers and masers, of atomic power and space-ships, of heart transplants and the creation of the molecule of synthetic life in the laboratory. It is harder to realize that this is equally the era of social and political change and achievement equal to the magnitude of technological advance. Israel is the evidence that Man as Citizen -- no less than Man as Scientist -- can invent his future. From the ghastly ashes of a continent gone crazy, a new nation grew up in the Middle East that has shown mankind that a small nation can -- in a moment of time -- become a great nation, an independent nation, a creative nation, and a strong nation -- no matter what the obstacles! And the way that was followed was freedom -- not the way of tyranny that takes shortcuts across the quicksand of false promise -- but the harder, yet firmer, course of freedom. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No_1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This fonn is for use in nominating or requesting detenninations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How lo Complele /he Nalional Register of Historic Places Regislralion Form. If any item does not 1\PPJY .to..tbe property being documented, enter "N/N for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas f sig¢(ECE I V'!:V~80 ~·~~~s;~;~::;;;"'"'''"" \ AUG- 8 2014 Other names/site number: \:lAT.REE: STEROF HlSTOOlGPLACES Name of related multiple property listing: _ r~·~IQ~LPAR !< SEI1Y ICE NIA (Enter "N/ A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing 2. Location Street & number: 3900 Manchester Boulevard City or town: Inglewood State: _..C=A=-==~-- County: Los Angeles Not For Publication: D Vicinity: D 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x__ meets _does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national _statewide ..,X_ local Applicable National Register Criteria: _A _B _x_c D Jenan Saunders, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date California State Office of Historic Preservation State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property ·- meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Interview with Neil Hartigan # ISG-A-L-2010-012.01 Interview # 1: March 18, 2010 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Neil Hartigan # ISG-A-L-2010-012.01 Interview # 1: March 18, 2010 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Thursday, March 18, 2010. My name is Mark DePue; I’m the director of oral history at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, and it’s my pleasure today to be interviewing General Neil Hartigan. How are you this afternoon, General? Hartigan: (laughs) I’m fine, Mark. How are you? We can dispense with the general part, though. (laughs) DePue: Well, it’s all these titles. You’re one of these people who has several titles. But we’ll go from there. It is a lot of fun to be able to sit down and talk to you. -

I Like Ike the Presidential Election of 1952 1St Edition Ebook

I LIKE IKE THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 1952 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Robert Greene | 9780700624058 | | | | | I Like Ike The Presidential Election of 1952 1st edition PDF Book I Like Ike: The Presidential Election of walks the reader carefully and richly back through all of that: Eisenhower versus Stevenson and the downfall of the delegate leaders for their respective nominations in a contest proving that the new Democratic majority was not invincible but one that Republicans would not replicate for a long time to come. Farrell Dobbs. Error rating book. In an election contest that was evidently deviant from, rather than diagnostic of, its predecessors and its successors. Russell, Averell Harriman and Earl Warren. Vincent Hallinan. Friend Reviews. On June 4, Eisenhower made his first political speech in his home town of Abilene, Kansas. Mike Monroney , President Truman and a small group of political insiders chose Sparkman, a conservative and segregationist from Alabama, for the nomination. Stevenson , he came from a distinguished family in Illinois and was well known as a gifted orator, intellectual, and political moderate. Adlai Stevenson for his part would have nothing to do with television at all and condemned Eisenhower's use of the medium, calling it "selling the presidency like cereal". North Dakota. While there are no shortage of books about Eisenhower or his years as president, nearly seven decades after his election there are only two histories about it. Incumbent Democratic President Harry S. Draft Eisenhower movements had emerged ahead of the election , mostly in the Democratic Party ; in July , Truman offered to run as Eisenhower's running mate on the Democratic ticket if Douglas MacArthur won the Republican nomination. -

Harry Byrd and the 1952 Presidential Election James R

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Faculty Publications History 1978 Revolt in Virginia: Harry Byrd and the 1952 Presidential Election James R. Sweeney Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Sweeney, James R., "Revolt in Virginia: Harry Byrd and the 1952 Presidential Election" (1978). History Faculty Publications. 5. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs/5 Original Publication Citation Sweeney, J.R. (1978). Revolt in Virginia: Harry Byrd and the 1952 presidential election. Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 86(2), 180-195. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVOLT IN VIRGINIA Harry Byrd and the 1952 Presidential Election by JAMES R. SWEENEY* PRIOR to 1952 Virginians had voted for a Republican president only once in the twentieth century. In 1928 Herbert Hoover defeated Al Smith by 24,463 votes. Extraordinary circumstances produced that result. Smith's Catholicism and his opposition to Prohibition made him unacceptable to many Virginians, including the politically powerful Methodist Bishop James Cannon, Jr. By 1952 an entirely different political situation had developed in the Democratic Party, but Virginia Democrats were confronted with the same problem as in 1928, namely, whether or not to support a presidential candidate for whom they had a distinct lack of enthusiasm.' Since the incep- tion of the New Deal, the dominant wing of the Virginia Democratic Party, headed by Senator Harry F. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations

UC Berkeley Dissertations Title Insuring the City: The Prudential Center and the Reshaping of Boston Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4b75k2nf Author Rubin, Elihu James Publication Date 2009-09-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California Transportation Center UCTC Dissertation No. 149 Insuring the City: The Prudential Center and the Reshaping of Boston Elihu James Rubin University of California, Berkeley Insuring the City: The Prudential Center and the Reshaping of Boston by Elihu James Rubin B.A. (Yale University) 1999 M.C.P. (University of California, Berkeley) 2004 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Paul Groth, Chair Professor Richard Walker Professor C. Greig Crysler Fall 2009 Insuring the City: The Prudential Center and the Reshaping of Boston © 2009 by Elihu James Rubin Abstract Insuring the City: The Prudential Center and the Reshaping of Boston by Elihu James Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Paul Groth, Chair Insuring the City examines the development of the Prudential Center in Boston as a case study of the organizational, financial, and spatial forces that large insurance companies wielded in shaping the postwar American city. The Prudential Center was one of seven Regional Home Offices (RHOs) planned by Prudential in the 1950s to decentralize its management. What began as an effort to reinvigorate the company’s bureaucratic makeup evolved into a prominent building program and urban planning phenomenon, promoting the economic prospects of each RHO city and reshaping the geography of the business district. -

Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4w1007j8 No online items Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection Processing Information: Preliminary arrangement and description by Rosanne Barker, Viviana Marsano, and Christopher Husted; latest revision D. Tambo, D. Muralles. Machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou, latest revision A. Demeter. Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections/ © 2000-2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Mss 107 1 Catalog Collection Preliminary Guide to the Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection, ca. 1850-1968 Collection number: Mss 107 Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Contact Information: Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections/ Processing Information: Preliminary arrangement and description by Rosanne Barker, Viviana Marsano, and Christopher Husted; latest revision by D. Tambo and D. Muralles. Date Completed: Dec. 30, 1999 Latest revision: June 11, 2012 Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou, A. Demeter © 2000, 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection Dates: ca. 1850-1968 Collection number: Mss 107 Creator: Romaine, Lawrence B., 1900- Collection Size: ca. 525.4 linear feet (about 1171 boxes and 1 map drawer) Repository: University of California, Santa Barbara.