1 Worship and Arts Sunday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choir Anniversary

CHOIR ANNIVERSARY CULTURAL RESOURCES Sunday, August 21, 2011 Tammy L. Kernodle, Guest Cultural Resources Commentator Miami University, Associate Professor of Musicology I. The History Section Since the first gospel choir appeared in the 1930s at the Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago, it has remained one of the most recognized symbols of Black Church culture and Christendom in general. In the decades since Thomas Dorsey, Theodore Frye, Lucie Campbell, and several other individuals advanced the gospel choir as one of the significant agents of worship, the nature of music ministry has evolved extensively. Today many congregations have multiple choirs that are defined by age and gender as well as by the type of repertoire performed. Despite diverse and sometimes controversial ideologies about the role of the choir within the Church and the appropriateness of certain types of music within the context of worship, the one unifying agent that draws all of these phenomenon together is the celebration of Choir Day or the Choir Anniversary. This celebration, outside of the annual concerts or musical programs, is one of the few moments within the life of the Black Church in which the importance of the ministry of music in the life of the Church and its role in extending the ministry of the Word is acknowledged. The history of the choir within black congregations is intertwined with that of the hymn and gospel song, which was advanced during the early 20th century through composers such as Charles Tindley, Lucie Campbell, and Thomas Dorsey. The emergence of both reflected the evolution of worship practices as African Americans moved from rural to urban environments, agrarian to industrial economic systems, and traditional to cosmopolitan life experiences. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

Lift Every Voice: Celebrating the African American Spirit

Lift Every Voice: Hear My Prayer Moses Hogan Celebrating the African American Spirit Set Me as a Seal Julius Miller Saturday, February 22. , 2014 7:30 pm Lord We Give Thanks to Thee Undine Smith Moore Campus Auditorium Lift Every Voice and Sing arr. Roland Carter South Bend Symphonic Choir How Great is Our God Chris Tomlin Naomi Penate, alto Jake Hughes, tenor CONDUCTOR BIOGRAPHIES For Every Mountain Kurt Carr Gwen Norwood, alto David Brock was born and raised in Benton Harbor, Mich. to the union of Walter and the late Doris Brock. He started playing I’m Determined Oscar Hayes the piano at the age of six and began taking lessons at age 11. He also began playing piano at churches when he was 11. Mr. Brock Hallelujah Elbernita “Twinkie” Clark performed in bands and orchestras throughout his education. He IU South Bend Gospel Choir attended Olivet College where he studied music. Mr. Brock is Formatted: Font: Not Bold currently employed at Benton Harbor High School as a pianist and Dich Teure Halley Richard Wagner assistant music teacher. He teaches keyboard theory and voice. He has been playing the keyboard for 44 years. Witness Hall Johnson Marvin Curtis, dean of the Ernestine M. Raclin School of You Can Tell the World Margaret Bonds the Arts at Indiana University South Bend is director of the South Denise Payton, soprano Bend Symphonic Choir. Dean Curtis has held positions at Intermezzo, Op. 118, No. #2 Johannes Fayetteville State University, California State University, Brahms Stanislaus, Virginia Union University, and Lane College. He earned degrees from North Park Troubled Water Margaret Bonds College, The Presbyterian School of Christian Education, Formatted: Indent: First line: 0.5" Maria Corley, piano and The University of the Pacific, and took additional studies at Westminster Choir College and The Julliard School of Music. -

Clark Booklet First Draft.Indd

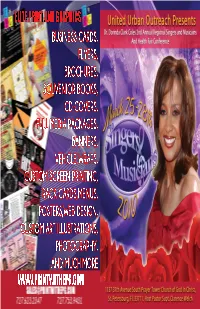

2930 34th St. South St. Pete, Fl 33711 Walk-ins Welcome ProfessionalPrP ooffessiilNilC&Wii Nail Care & Waxing 3059 18th Ave. South - St. Pete, Fl 33712 ForFoF r Ladies & Gentlemen United UrbanOutreach United United UrbanOutreach United Mon. – Thurs. (727) 686-0903 Cell - (727) 321-6263 Salon WeW Use OPI Products 9:30a.m.–7:00p.m. [email protected] 2020% Off On Birthday Fri. – Sat. 9:00a.m – 7:00p.m. Mon. - Thurs. Sunday: Closed 8:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. Fri. & Sat. Acrylic Nails Silk Wraps By Appointment (727) 906-8056 Greetings Gel Nails French Manicure Fiberglass Pink & White Dr. Dorinda Clark-Cole 2 39 God’s Richest Blessings to the Singers and Musicians Air - Conditioning, Refrigeration, & Appliances Conference, Bay Area. Quality & Integrity I am so blessed and honored to be here with all of the Ph: (727) 442-6312 or (727) 366-8844 Fax: (727) 242-2913 attendees of this monumental occasion. I am happy to come and share with you the Fax: (727) 242-2913 State Certified Contractors #CAC1815030 vision God gave me over 12 years ago. The vision was to develop the ministry of a Singers and Musicians Conference (SMC). The purpose of SMC is to give a Nathaniel Johnson - President platform/venue to up-and-coming gospel artists and musicians to express and showcase Licensed & Insured Over 25 Years Experience their God given talents. Sales/Service/Installations/Repairs/Maintenance Two years ago, we launched the first regional Singers and Musicians Conference in Birmingham, Alabama. This conference gave those who were unable to attend Detroit’s SMC, now known as the National SMC, a glimpse of what is done on the National level. -

Sound Business: Great Women of Gospel Music and the Rt Ansmission of Tradition Nina Christina Öhman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Sound Business: Great Women Of Gospel Music And The rT ansmission Of Tradition Nina Christina Öhman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Öhman, Nina Christina, "Sound Business: Great Women Of Gospel Music And The rT ansmission Of Tradition" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2646. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2646 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2646 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sound Business: Great Women Of Gospel Music And The rT ansmission Of Tradition Abstract From the 1930s to the present, women have played instrumental and visible leadership roles in the remarkable growth of African American gospel music. Through both creative and entrepreneurial activities, these women paved the way for the expansion of an emotive sacred music expression from the worship practices of southern migrants to audiences around the world. This dissertation focuses on the work of three cultural trailblazers, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, and Karen Clark Sheard, who stand out in the development of gospel music as virtuosic vocalists and pivotal figures whose sonic imprints can be heard both in sacred songs performed in churches and in American popular music. By deploying exceptional musicality, a deep understanding of African American Christianity, and an embrace of commercialism, the three singers have conserved and reworked musical elements derived from an African American heritage into a powerful performance rhetoric. -

The Mississippi Mass Choir

R & B BARGAIN CORNER Bobby “Blue” Bland “Blues You Can Use” CD MCD7444 Get Your Money Where You Spend Your Time/Spending My Life With You/Our First Feelin's/ 24 Hours A Day/I've Got A Problem/Let's Part As Friends/For The Last Time/There's No Easy Way To Say Goodbye James Brown "Golden Hits" CD M6104 Hot Pants/I Got the Feelin'/It's a Man's Man's Man's World/Cold Sweat/I Can't Stand It/Papa's Got A Brand New Bag/Feel Good/Get on the Good Foot/Get Up Offa That Thing/Give It Up or Turn it a Loose Willie Clayton “Gifted” CD MCD7529 Beautiful/Boom,Boom, Boom/Can I Change My Mind/When I Think About Cheating/A LittleBit More/My Lover My Friend/Running Out of Lies/She’s Holding Back/Missing You/Sweet Lady/ Dreams/My Miss America/Trust (featuring Shirley Brown) Dramatics "If You come Back To Me" CD VL3414 Maddy/If You Come Back To Me/Seduction/Scarborough Faire/Lady In Red/For Reality's Sake/Hello Love/ We Haven't Got There Yet/Maddy(revisited) Eddie Floyd "Eddie Loves You So" CD STAX3079 'Til My Back Ain't Got No Bone/Since You Been Gone/Close To You/I Don't Want To Be With Nobody But You/You Don't Know What You Mean To Me/I Will Always Have Faith In You/Head To Toe/Never Get Enough of Your Love/You're So Fine/Consider Me Z. Z. -

Good News for the Motor City: Black Gospel Music in Detroit by Joyce M

Good News for the Motor City: Black Gospel Music in Detroit by Joyce M. Jackson and James T. Jones, N Since the early 1930s Detroit has been one of the prime centers joyce M jackson is an ethnomusicologist/ folklorist and conducts research in Black mu for Black gospel music. Even though gospel was overshadowed in sic and culture. She is currently an assistant the 1960s by the pervasiveness of the Motown sound, the sacred professor in the Geography and Anthropology Department at Louisiana State University, Ba tradition always was strong in Black neighborhoods, co-existing tonRouge. with the secular. Through the years the two traditions have james T jones, N, a Detroit native, received influenced each other, and they both have served to meet the his master's degree in communication from constantly changing and expanding needs of the urban Black Western Michigan University. He currently writes on gospel and rhythm and blues music for the community. Features Department ofthe Detroit News, and Prior to the early 20th century most Afro-Americans lived in the plays the bass in a jazz quartet. rural South. However, with the outbreak of the World Wars, Detroit along with other industrial cities of the North held a promise of economic and social opportunities and personal freedom for southern Blacks, particularly in automobile and related industries. They came in hope of escaping a legal system of discrimination that prevented any improvements of their status. Unfortunately, life in the city did not meet the expectations of the migrants. The practice of discrimination in employment, housing, education and the use of public accomodations forced Blacks to create an alternate life style. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Donnie Mcclurkin

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Donnie McClurkin Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: McClurkin, Donnie Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Donnie McClurkin, Dates: October 6, 2016 and October 8, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 13 uncompressed MOV digital video files (6:28:49). Description: Abstract: Gospel singer and pastor Donnie McClurkin (1959 - ) released multiple successful gospel albums, including Donnie McClurkin and Live in London and More. He also founded and served as senior pastor of the Perfecting Faith Church in Freeport, New York. McClurkin was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 6, 2016 and October 8, 2016, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_068 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Gospel singer and pastor Donnie McClurkin was born on November 9, 1959 in Copiague, New York to Donald McClurkin, Sr. and Frances McClurkin. McClurkin joined the choir at Amityville Full Gospel Tabernacle. At the age of fifteen, he became a member of Benny Cummings and the King’s Temple Choir. McClurkin attended Walter G. O’Connell Copiague High School. McClurkin formed the McClurkin Singers with his older sisters and a neighbor; and in 1983, the group performed with the Tri-Boro Mass Choir, led by Albert Jamison, who introduced McClurkin to gospel singer James Cleveland, who became a mentor to McClurkin. McClurkin made annual visits to Los Angeles, California to sing with Cleveland at Cornerstone Institutional Baptist Church. -

Great Women of Gospel Music and the Transmission of Tradition

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Sound Business: Great Women Of Gospel Music And The Transmission Of Tradition Nina Christina Öhman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Öhman, Nina Christina, "Sound Business: Great Women Of Gospel Music And The Transmission Of Tradition" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2646. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2646 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2646 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sound Business: Great Women Of Gospel Music And The Transmission Of Tradition Abstract From the 1930s to the present, women have played instrumental and visible leadership roles in the remarkable growth of African American gospel music. Through both creative and entrepreneurial activities, these women paved the way for the expansion of an emotive sacred music expression from the worship practices of southern migrants to audiences around the world. This dissertation focuses on the work of three cultural trailblazers, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, and Karen Clark Sheard, who stand out in the development of gospel music as virtuosic vocalists and pivotal figures whose sonic imprints can be heard both in sacred songs performed in churches and in American popular music. By deploying exceptional musicality, a deep understanding of African American Christianity, and an embrace of commercialism, the three singers have conserved and reworked musical elements derived from an African American heritage into a powerful performance rhetoric. -

¡Bru Difficult Waters

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) 2042-LO906 b3 H31/39 9N01 V I 3A0' W13 04L£ A1N33219 A1NOW LITT 92T 2 005220 T00 I'll IIInItltltttE'III"IEtllttltttltttlltl"Itt'II"I'II 999 0919 11200W34L£339L090611 906 1I9I0-2 ************* cum täA00M{Bit THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT JANUARY 23, 1999 Retailers Urge C iI I_ I_ 1=1= TI la l= Lopez Steers WMI CI CI S 17; A 1= Labels To Join WEA In Source -Tagging ¡bru Difficult Waters BY ED CHRISTMAN NEW YORK-With WEAs an- BY ADAM WHITE exploited the opportunity to talk the nouncement that in March it LONDON-When the Warner Music company down, when they weren't will begin placing electronic Group's 1998 financial results are preoccupied by Universal's takeover article surveillance (EAS) tags published next of PolyGram or in product during the manufac- month, its interna- Sir Colin South - tional division, gate's travails at Big `Week' Boosts under chair- EMI. man /CEO Ramon Naysayers have Hi- Fi /Elektra's Wea Lopez, is sure to even suggested be praised by the WARNER MUSIC that Lopez will oINTERNATIONAL Marvelous 3 turing phase (BillboardBul- company's chiefs LOPEZ leave the Warner letin, Jan. 14) -a practice for an outstanding Music fold within BY LARRY FLICK known as source- tagging- performance in BILLBOARD EXCLUSIVE two years -some NEW YORK -As the Jan. 26 many merchants are calling on difficult trading insiders also sub- release of Marvelous 3's Hi- the extra -strength new album featuring the other majors to follow suit. -

Bishop J. Drew Sheard Was Born on January 1, 1959 to Bishop John

Bishop J. Drew Sheard was born on January 1, 1959 to Bishop John Henry Sheard and Willie Mae Sheard in Detroit, Michigan.[1] He was raised as a Pentecostal Christian in the Church of God in Christ with his younger brother, Ethan Blake Sheard, who is also a pastor in the Church of God in Christ denomination.[4] Upon graduating high school, he attended the Wayne State University, where he earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Education, and a Master of Education degree in Mathematics, and while balancing a career in Christian ministry as a clergyman, he also worked as a secondary school math teacher in the Detroit Public Schools District.[2][5] In 1984, he married Karen Clark Sheard, a Gospel singer and member of the famed Gospel vocal group, The Clark Sisters, who was also the daughter of the famed Gospel Choir director, Mattie Moss Clark, who served as one of the international music department presidents of the Church of God in Christ denomination. For several years, he helped Mattie Moss Clark manage the Clark Sisters' singing career throughout the 1980s until they parted their separate ways to endeavor on their own individual careers, and from then on became his wife, Karen's personal music career manager.[6] Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Bishop Sheard served in various capacities with the Church of God in Christ denomination under the tutelage of his father, Bishop John H. Sheard, including as a choir director, chairman of both local and state youth departments in the Church of God in Christ denomination, as a National Adjutant Overseer, and eventually as an Executive Secretary of the International Youth Department for the Church of God in Christ denomination. -

The Essential Gospel Music Listening Library

The Journal of Traditions & Beliefs Volume 1 Article 10 April 2014 The Essential Gospel Music Listening Library Stephanie L. Barbee Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jtb Part of the African American Studies Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Barbee, Stephanie L. (2014) "The Essential Gospel Music Listening Library," The Journal of Traditions & Beliefs: Vol. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jtb/vol1/iss1/10 This Discography is brought to you for free and open access by the Michael Schwartz Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Traditions & Beliefs by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barbee: The Essential Gospel Music Listening Library Volume 1, Number 1, Fall 2009 59 Discography The Essential Gospel Music Listening Library Edited and with an Introduction by Stephanie L. Barbee Compiled by the Members of Spiritual Gifts, A Professional Black Sacred Music Repertory Ensemble (2009) oth students and scholars at the In completing this particular collection, university level can benefit from using identifying the release date and respective record a catalog of African American sacred label was very time consuming, especially for B music, because, in African American songs released in the early twentieth century, the communities, music often serves as a diagram, era of traditional Gospel music. Recordings of tracing the growth and stagnations of African Mahalia Jackson’s music, for example, are often Americans throughout their history in the re-mastered to provide better sound quality, and United States.