FMT 69(2) Alexander and Taylor 1 to Be Published in W Inter 2010 Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listing of All EMS Agencies with Their Agency Codes

Agency Name (D1.2) A.B. Shaw Fire Department (1099) A.E. Crandall Hook and Ladder Co., Inc. (0212) Ace Ambulance Service, LLC (Hunter Ambulance) (0884) Adams Fire Company, Inc. (3199) Addison Volunteer Fire Department Ambulance Corps (5015) Afton Emergency Squad (0811) Air Methods Corp. Rocky Mountain Holdings (LifeNet New York; Albany Med Flight; Stat Flight) (0767) Akron Fire Company, Inc. (1426) Akwesasne Mohawk Ambulance (4498) Alabama Fire Department (1899) Alamo Ambulance Service, Inc. (1311) Albany County Sheriff's Department Advanced Life Support (0184) Albany County Sheriff's Office EMS Unit (6229) Albany Department of Fire & Emergency Services, City of (0142) Albany-Schenectady-Greene Co. Ag. Societies, Inc. (Altamont Fair Ambulance) (0139) Albertson Fire Department (2998) Albion Fire Department Emergency Squad (3619) Alden EMS Department (1437) Alert Engine, Hook, Ladder & Hose Co., No. 1, Inc. (0253) Alexander Fire Department, Inc. (1818) Alexandria Bay Volunteer Fire Department (2212) Allegany Fire District, Town of (0775) Allegany Indian Reservation Vol. Fire Department (Seneca Nation Rescue) (0433) Allegany Rescue and EMS, Inc. (0982) Almond Volunteer Fire Department (0225) Alplaus Fire Department (4693) ALS Services, Inc. (7199) Altamont Rescue Squad, Inc. (0117) Altmar Fire Department (3799) Alton Fire Company of Alton, New York, Inc. (5813) Altona Volunteer Fire Department Rescue Squad (0930) Amagansett Fire Department Ambulance (8139) Amber Ambulance Inc. (3313) Amber Fire Department, Inc.(1083) Ambulance Committee of the Moriches, Inc. (East Moriches Community Ambulance) (5158) Ambulance Service of Fulton County, Inc. (1712) AmCare Ambulance Service, Inc. (3217) Amenia Rescue Squad (1320) Amity Rescue Squad, Inc. (0213) Amityville Fire Department (5137) Amsterdam Fire Department (0554) Andes Fire Department, Inc. -

2020 Fresno-Kings Unit Fire Plan

Fresno-Kings Unit 5/03/2020 UNIT STRATEGIC FIRE PLAN AMENDMENTS Page Numbers Description Updated Date Section Updated Updated of Update By 4/30/20 Appendix A 36-38 Fire Plan Projects B. Garabedian 4/30/20 Appendix B 40-41 Added Wildland Activity B. Garabedian Chart 4/30/20 Appendix C 42 Update Ignition Data B. Garabedian 4/30/20 Various 103-119 2019 Accomplishment B. Garabedian i TABLE OF CONTENTS UNIT STRATEGIC FIRE PLAN AMENDMENTS .................................................................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... ii SIGNATURE PAGE ............................................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 SECTION I: UNIT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................. 3 UNIT DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................... 3 FIRE HISTORY ................................................................................................................................ 4 UNIT PREPAREDNESS AND FIREFIGHTING CAPABILITIES ..................................................... 4 SECTION II: COLLABORATION.......................................................................................................... -

Alaska Fire Season 2009

Fire #164 Broken Snowshoe courtesy of SWS ALASKA FIRE SEASON 2009 Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report - AICC Table of Contents 1 Index 2 2009 Alaska Fire Season Summary 3 Fire Weather Summary 5 Fires Narratives with Perimeter Maps 18 Railbelt Complex 24 Crazy Mt. Complex 37 Incident Management Team Assignments / Overhead Assignments 38 Statewide Totals by Month 39 Statewide Fire Statistics - Averages 40 Statewide Fires and Acres by Protection Agency and Management Option 41 Statewide Fires and Acres by Landowner and Management Option 42 Alaska Fire Service Protection Fires and Acres by Zone and Management Option U.S. Forest Service Protection Fires and Acres by Forest and Management Option 43 State of Alaska Fires and Acres by Region / Area and Management Option 44 Bureau of Land Management Fires and Acres by Field Office and Landowner 45 National Park Service Fires and Acres by Park and Landowner 46 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fires and Acres by Refuge and Management Option 47 State of Alaska Fires and Acres by Administrative Unit and Management Option 48 10 year Numbers 49 Numbers by the Decade 50 T2 EFF Crew Assignments, Alaska Agency Crew Assignments, L48 Crews in Alaska 51 Alaska EFF T2 Crew Assignments 53 Village Crew Wages 1 2009 Alaska Fire Season Summary The National Seasonal Assessment workshop was held in mid April for Alaska. The initial fire potential predictions made for the 2009 Alaska season all indicated a lower than average number of acres would be burned. The AICC Predictive Services group, the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy, and a private Meteorologist all predicted a slow Alaskan fire season. -

Municipal Fire Protection Services Report

A Report on the Operational Readiness of Municipal Fire Protection Services Throughout Newfoundland and Labrador 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................. 3 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................ 4 DESCRIPTION OF THE MUNICIPAL FIRE SERVICE ........................................ 6 MUNICIPAL FIRE PROTECTION ASSESSMENTS ......................................... 11 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................... 19 Appendix A - List of Newfoundland and Labrador Fire Departments ............. 20 Appendix B - Overview of Individual Municipal Fire Department Assessments by Fire Department ............................................................................... 25 Appendix C - FES-NL Municipal Fire Department Assessment Criteria ......... 40 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Report on the Operational Readiness of Municipal Fire Protection Services for Newfoundland and Labrador is based on data collected from the municipal fire protection services assessments which were completed over a period of 48 months, from September 2010 to August 31, 2014. The results of assessments performed for this report, and the analysis of the data, must be viewed in context with the current structure of the fire service throughout Newfoundland and Labrador and represents a snapshot in time. Some work has occurred since the initial assessments that may have contributed to certain -

Vegetation Fires and Global Change Challenges for Concerted International Action

A White Paper directed to the United Nations and International Organizations A Action Challenges for Concerted International Fires and Global Change Vegetation The White Paper “Vegetation Fires and Global Change” is a global state-of-the- art analysis of the role of vegetation fires Vegetation Fires and in the Earth System and is published as a collective achievement of the world’s most renowned scientists and research Global Change groups working in fire science, ecology, atmospheric chemistry, remote sensing and climate change modeling. The aim of the White Paper is to support the en- deavour of the United Nations and its af- Challenges for Concerted International Action filiated processes and networks, notably A White Paper directed to the United Nations the United Nations International Strat- egy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR), and International Organizations the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005- 2015 “Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters” and the Global Wildland Fire Network, to address global vegetation fires for the benefit of the global environment and humanity. The White Paper provides insight into the complexity of global vegetation fire issues and rationale for coordinated, in- ternational action in crossboundary fire management at global scale. This White Paper has been commis- sioned by the UNISDR Wildland Fire Ad- visory Group through its Secretariat, the Global Fire Monitoring Center (GFMC), Associate Institute of the United Nations University and Secretariat of the Global Wildland Fire Network. -

Wildland Fire Evacuation Plan for the Harmony Grove Village South Community

Wildland Fire Evacuation Plan for the Harmony Grove Village South Community Prepared for: Rancho Santa Fe Fire Protection District San Diego County, California Prepared by: 605 Third Street Encinitas, California 92024 MAY 2018 Printed on 30% post-consumer recycled material. Wildland Fire Evacuation Plan Harmony Grove Village South Community TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page No. 1 QUICK REFERENCE – WILDLAND FIRE EVACUATION PLAN .........................1 1.1 Nearest Medical Facilities....................................................................................... 4 1.2 Register to Receive Emergency Alerts ................................................................... 9 1.3 Get Involved in Community Readiness .................................................................. 9 1.4 Evacuation Plan Purpose and Limitations ............................................................ 10 2 BACKGROUND ..............................................................................................................13 3 SAN DIEGO COUNTY EVACUATION PLANNING SUMMARY ..........................15 3.1 Evacuation Objectives .......................................................................................... 16 3.2 Evacuation Coordination Process ......................................................................... 18 3.3 Evacuation Response Operations .......................................................................... 19 3.3.1 Evacuation Points and Shelters ................................................................. 19 3.3.2 -

Fire Management Today

Fire today ManagementVolume 66 • No. 1 • Winter 2006 PRESCRIBED FIRE CASE STUDIES, DECISION AIDS, AND PLANNING GUIDES United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Dedication This special issue of Fire Management Today devoted to prescribed fire is dedicated to all the individuals from around the world who have been killed or seriously injured while engaged in a prescribed burning operation. This would include fatality incidents in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Portugal, the United States, and no doubt other regions of the world. It is our sincerest hope that this publication will in some way contribute to an enduring culture where concern for the safety of personnel involved in prescribed burning is an integral part of the planning and operational procedures in the future. Martin E. Alexander and David A. Thomas Issue Coordinators Editors’ note: This issue of Fire Management Today reprints articles from early editions of the journal, some of them decades old. Although the articles appear in today’s format, the text is reprinted largely verbatim and therefore reflects the style and usage of the time. We made minor wording changes for clarity, added intertitles and metric conversions where needed, and occasionally broke up paragraphs to improve readability. All illustrations are taken from the original articles. Fire Management Today is published by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. The Secretary of Agriculture has determined that the publication of this periodical is necessary in the transaction of the public business required by law of this Department. Fire Management Today is for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

Tuolumne-Calaveras Unit Fire Plan 2020

Tuolumne-Calaveras Unit 2020 Strategic Fire Plan Nick Casci, Unit Chief TUOLUMNE -CALAVERAS UNIT FIRE PLAN 2020 Contents Strategic Fire Plan ............................................................................................................................ 1 SIGNATURE PAGE ...................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 5 SECTION I: UNIT OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................... 6 Socioeconomic .......................................................................................................................... 7 Fire Environment ....................................................................................................................... 8 Fire Protection Responsibilities ................................................................................................. 8 Unit Preparedness and Firefighting Capabilities ........................................................................ 9 SECTION II: COLLABORATION ................................................................................................. 12 COMMUNITY/AGENCIES/FIRE SAFE COUNCILS ................................................................ 12 SECTION III: VALUES ............................................................................................................... -

Yarnell Hill Fire

Yarnell Hill Fire June 30, 2013 Serious Accident Investigation Report September 23, 2013 Cover Photo: Raising the United States and State of Arizona flags at the Granite Mountain crew’s deployment site. Courtesy of the Southwest Area Type 1 Incident Management Team. In Memory Of Andrew Sterling Ashcraft Robert E. Caldwell Travis Clay Carter Dustin James DeFord Christopher A. MacKenzie Eric S. Marsh Grant Quinn McKee Sean M. Misner Scott Daniel Norris Wade S. Parker John J. Percin, Jr. Anthony M. Rose Jesse James Steed Joe B. Thurston Travis Turbyfill William Howard ‘Billy’ Warneke Clayton Thomas Whitted Kevin J. Woyjeck Garret Zuppiger Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 1 The Investigation Process ............................................................................................... 5 Background ................................................................................................................... 8 Part One: Factual & Management Report ................................................................. 11 Narrative ...................................................................................................................... 11 Friday, 28 June 2013 ................................................................................................ 11 Saturday, 29 June 2013 ............................................................................................ 12 Sunday, 30 June 2013 ............................................................................................. -

2013-Jul-Aug.Pdf

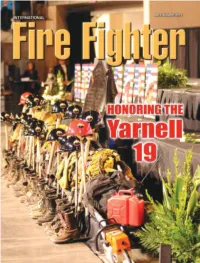

NOT ALL PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES GET SIGNING BONUSES. GLOBETURNOUTGEAR.COM ™ ® DuPont KEVLAR brand fi ber provides high-strength, GLOBE and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of Globe Holding Company, LLC. DUPONT, KEVLAR permanent fl ame and thermal resistance, and proven durability. and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company or its affi liates. 1:40 PM contents JULY/AUGUST 2013 JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF FIRE FIGHTERS/VOL. 96 NO. 3 FEATURES ON THE COVER Honoring the Yarnell 19 Public memorial service honors fallen hotshots ..............................18 INSIDE Wildfire season starts early The Battle Over Combining Police and Fire P. 20 Why the PSO model is a bad idea ..................................................10 General President’s Message Furloughs Leave Bases Less Safe Public Safety Before Politics ................................................5 Sequester threatens public safety on military bases ........................13 General Secretary-Treasurer’s Message IAFF Disaster Relief Back to Basics ....................................................................7 Tornados, flooding affect members..................................................14 Letters..............................................................................8 P. 23 Across the IAFF ..........................................................22 Always on the Frontline ............................................34 On the Road ................................................................36 -

Potential Formation of a New Fire District

I Fire Department Funding and Governance Analysis Tooele County January 2021 Fire Department Funding and Governance Analysis Tooele County TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................. 3 SECTION I: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 4 SECTION II: METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 Kick-Off Meeting ................................................................................................................................... 6 Stakeholder Interviews .......................................................................................................................... 6 Data Collection ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Background Research .......................................................................................................................... 7 SECTION III: BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................... 8 Tooele County Geography and Population ........................................................................................... 8 Study Objectives .................................................................................................................................. -

June 22, 2015 Laurence Crabtree Eldorado National Forest

June 22, 2015 Laurence Crabtree Eldorado National Forest Supervisor C/o Jennifer Ebert Eldorado National Forest 100 Forni Road Placerville, California 95667 Sent via email to: [email protected] Re: Comment on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Proposed King Fire Restoration Project Dear Supervisor Crabtree, These comments are submitted on behalf of Sierra Forest Legacy, the Sierra Club, and the Center for Sierra Nevada Conservation. We have reviewed the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for the King Fire Restoration Project and associated documents. In addition, we have attended the public Forest Service King Fire Open House in Placerville and attended four site visits with various staff from the Forest Service, scientists and stakeholders since the fire event. Sierra Forest Legacy is very familiar with this landscape and we have been engaged in fire restoration efforts with the Forest Service since 1992 post-Cleveland Fire Recovery. In 1993 we successfully negotiated increased burned tree retention standards for the Cleveland Fire Recovery area which, to our knowledge, was the first time larger fire-killed trees were left standing for future ecological benefits in the Sierra Nevada. The concept of “life- boating” large ecological structures (large stand snags, large logs) into the recovering forest was a new concept at the time. The Eldorado National Forest should be proud of current and former staff who led the way in supporting what is now a fundamental ecological concept, twenty-three years ago. The purpose of our DEIS comments is to help inform and influence your final decision to choose a post-fire restoration strategy that provides for ecological integrity, ecosystem resilience, and species viability throughout the restoration process and to ensure that future generations may experience and enjoy a structurally and biologically complex, and ecologically rich post-fire landscape.