Mercy Otis Warren, a Case in Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margaret Fuller: the Self-Made Woman in the Nineteenth Century

Ad Americam. Journal of American Studies 19 (2018): 143-154 ISSN: 1896–9461, https://doi.org/10.12797/AdAmericam.19.2018.19.10 Jolanta Szymkowska-Bartyzel Institute of American Studies and Polish Diaspora Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland https://orcid.org/0000–0002–3717–6013 Successful Against All Odds? – Margaret Fuller: The Self-Made Woman in the Nineteenth Century Margaret Fuller was an American philosopher, writer, journalist and one of the first gen- der theorists. The article examines Fuller’s work and life in the context of 19th century American culture and social determinants influencing women’s lives. From a very early age, Fuller perceived her role in society different from the role designed for her as a bio- logical girl by the cultural model of the times she lived in. The article focuses on Fuller’s achievements in the context of the self-made man/woman concept. Key words: Margaret Fuller, self-made man, self-made woman, Benjamin Franklin, Tran- scendentalism, 19th century America, concept of success Do not follow where the path may lead. Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail. A quote attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson One of the key concepts that formed the basis of American exceptionalism and American foundational mythology in the 18th century, apart from religious predes- tination, political liberty and democracy, was the concept of success. The concept has its roots in Protestantism. Calvinists who “believed that each person had a calling, which entitled fulfilling one’s duty to God through day-to-day work in disciplined, rational labor. -

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American 'Revolution'

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American ‘Revolution’ Katherine Harper A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Arts Faculty, University of Sydney. March 27, 2014 For My Parents, To Whom I Owe Everything Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... i Abstract.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One - ‘Classical Conditioning’: The Classical Tradition in Colonial America ..................... 23 The Usefulness of Knowledge ................................................................................... 24 Grammar Schools and Colleges ................................................................................ 26 General Populace ...................................................................................................... 38 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 45 Chapter Two - Cato in the Colonies: Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................... 47 Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................................................... 49 The Universal Appeal of Virtue ........................................................................... -

Presidents' Day Family

Schedule at a Glance Smith Center Powers Room Learning Center The Pavilion Exhibit Galleries Accessibility: Performances Hands-on | Crafts Performances | Activities “Make and Take” Craft Activities Special Activities Learning Wheelchairs are available Shaping A New Nation Suffrage Centennial Center at the Visitor Admission 10:00 Desk on a first come, first served basis. Video Popsicle presentations in the Museum Stick Flags 10:30 Mini RFK 10:00 – 11:00 Foyer Elevators are captioned for visitors John & Abigail Adams WPA Murals Smith Center who are deaf or hard 10:30 – 11:10 Suffragist 10:00 – 11:30 Kennedy Scrimshaw of hearing. 11:00 Read Aloud Sashes & Campaign Hats 10:30 – 11:30 10:45 – 11:15 Sunflowers & Buttons James & Dolley Madison 10:00 – 12:30 10:00 – 12:15 Powers Café 11:30 11:10 – 11:50 Colonial Clothes Lucretia Mott Room 11:00 – 12:15 11:15 – 11:40 Adams Astronaut Museum Tour 11:15 – 12:20 Helmets 11:30 – 12:15 12:00 Eleanor Roosevelt 11:15 – 12:30 Restrooms 11:50 – 12:30 PT 109 Cart 12:30 Sojourner Truth Protest Popsicle 12:00 – 1:00 Presidential Press Conference 12:15 – 1:00 Posters Stick Flags 12:30 – 1:00 Museum Evaluation Station Presidential 12:00 – 1:30 12:00 – 1:30 Homes Store 1:00 James & Dolley Madison 12:30 – 1:30 Pavilion Adams Letter Writing 1:00 – 1:30 Astronaut Museum 1:00 – 1:40 to the President Space Cart Lucretia Mott Helmets Lobby 12:30 – 2:15 1:00 – 2:00 1:30 Eleanor Roosevelt 1:15 – 1:45 1:00 – 2:00 Entrance 1:30 – 2:00 2:00 John & Abigail Adams Sojourner Truth 2:00 – 2:30 2:00-2:30 Museum Tour Zines Scrimshaw 2:00 – 2:45 1:00 – 3:30 Mini 2:00 – 3:00 Sensory 2:30 Powerful Women Jeopardy WPA Murals Accommodations: 2:30 – 3:00 2:00 – 3:30 Kennedy The John F. -

Mercy Otis Warren-2

Mercy Otis Warren Did you know that Mercy Otis Warren wrote a book that was 1,317 pages long? I am going to tell you all about Mercy Otis Warren’s life. Why is she so important? Don't worry, I am going to tell you in this biography. I will first tell you about when she was born, where she was born, and about her childhood. Mercy Otis Warren was born on September 28,1728 in Barnstable Massachusetts. She died on October 19,1814 in Plymouth, she was 86 years old, and known as the First Lady of revolution. Mercy's favorite subject was American independence. Mercy expressed her feelings by reading, writing, and discussing about politics. Mercy had a very harsh childhood, Mercy was also a farmer with her kin. Mercy had 13 brothers and sisters, but only 6 of them survived to adult life. Now I will tell you about Mercy Otis Warren's adult life. Growing up, she wrote plays, books, and poems, and also had five kids. Another accomplishment that Mercy had in her adult life, is she brought food and raised money to help the war camps. Furthermore, she raised money for them, and made clothes for the soldiers who were in the Revolutionary war. Mercy wrote a play called “ The Blockheads” that was about how women were just as good as men were. In 1790, she published a copy of her poems and plays. Mercy was one of the most educated women in her country. I will now tell you about Mercy's contributions to the Revolutionary war. -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ). -

Abigail Adams As a Typical Massachusetts Woman at the Close of the Colonial Era

V/ax*W ad Close + K*CoW\*l ^V*** ABIGAIL ADAMS AS A TYPICAL MASSACHUSETTS WOMAN AT THE CLOSE OF THE COLONIAL ERA BY MARY LUCILLE SHAY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1917 - UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS m^ji .9../. THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ./?^..f<r*T) 5^.f*.l^.....>> .&*r^ ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF i^S^«4^jr..^^ UA^.tltht^^ Instructor in Charge Approved :....<£*-rTX??. (QS^h^r^r^. lLtj— HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF ZL?Z?.f*ZZS. 376674 * WMF ABIGAIL ARAMS AS A TYPICAL MASSACHUSETTS '.70MJEN AT THE CLOSE OP THE COLONIAL ERA Page. I. Introduction. "The Woman's Part." 1 II. Chapter 1. Domestic Life in Massachusetts at the Close of the Colonial Era. 2 III. Chapter 2. Prominent V/omen. 30 IV. Chapter 3. Abigail Adacs. 38 V. Bibliography. A. Source References 62 B. Secondary References 67 I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/abigailadamsastyOOshay . 1 ABIJAIL ARAMS A3 A ISP1CAL MASSACHUSETTS .VOMAIJ aT THE GLOSS OF THE COLOHIAL SEA. I "The Woman's Part" It was in the late eighteenth century that Abigail Adams lived. It was a time not unlike our own, a time of disturbed international relations, of war. School hoys know the names of the heroes and the statesmen of '76, but they have never heard the names of the women. Those names are not men- tioned; they are forgotten. -

John-Adams-3-Contents.Pdf

Contents TREATY COMMISSIONER AND MINISTER TO THE NETHERLANDS AND TO GREAT BRITAIN, 1784–1788 To Joseph Reed, February 11, 1784 Washington’s Character ....................... 3 To Charles Spener, March 24, 1784 “Three grand Objects” ........................ 4 To the Marquis de Lafayette, March 28, 1784 Chivalric Orders ............................ 5 To Samuel Adams, May 4, 1784 “Justice may not be done me” ................... 6 To John Quincy Adams, June 1784 “The Art of writing Letters”................... 8 From the Diary: June 22–July 10, 1784 ............. 9 To Abigail Adams, July 26, 1784 “The happiest Man upon Earth”................ 10 To Abigail Adams 2nd, July 27, 1784 Keeping a Journal .......................... 12 To James Warren, August 27, 1784 Diplomatic Salaries ......................... 13 To Benjamin Waterhouse, April 23, 1785 John Quincy’s Education ..................... 15 To Elbridge Gerry, May 2, 1785 “Kinds of Vanity” .......................... 16 From the Diary: May 3, 1785 ..................... 23 To John Jay, June 2, 1785 Meeting George III ......................... 24 To Samuel Adams, August 15, 1785 “The contagion of luxury” .................... 28 xi 9781598534665_Adams_Writings_791165.indb 11 12/10/15 8:38 AM xii CONteNtS To John Jebb, August 21, 1785 Salaries for Public Officers .................... 29 To John Jebb, September 10, 1785 “The first Step of Corruption”.................. 33 To Thomas Jefferson, February 17, 1786 The Ambassador from Tripoli .................. 38 To William White, February 28, 1786 Religious Liberty ........................... 41 To Matthew Robinson-Morris, March 4–20, 1786 Liberty and Commerce....................... 42 To Granville Sharp, March 8, 1786 The Slave Trade............................ 45 To Matthew Robinson-Morris, March 23, 1786 American Debt ............................ 46 From the Diary: March 30, 1786 .................. 49 Notes on a Tour of England with Thomas Jefferson, April 1786 ............................... -

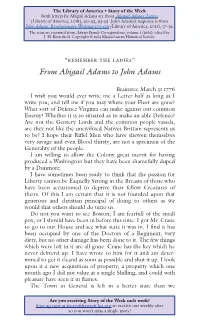

From Abigail Adams to John Adams

The Library of America • Story of the Week Both letters by Abigail Adams are from Abigail Adams: Letters (Library of America, 2016), 90–93, 93–95. John Adams’s response is from John Adams: Revolutionary Writings 1775–1783 (Library of America, 2011), 57–59. The texts are reprinted from Adams Family Correspondence, volume 1 (1963), edited by J. H. Butterfield. Copyright © 1963 Massachusetts Historical Society. “REMEMBER THE LADIES” From Abigail Adams to John Adams Braintree March 31 1776 I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone? What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence? Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be? I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people. I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore. I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us. Do not you want to see Boston; I am fearfull of the small pox, or I should have been in before this time. -

CHRONOLOGY of WOMEN's SUFFRAGE 1776 Abigail Adams

CHRONOLOGY of WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE 1776 Abigail Adams writes to her husband, John Adams, asking him to "remember the ladies" in the new code of laws. Adams replies the men will fight the "despotism of the petticoat. Thus begins the long fight for Women's suffrage. 1869 Wyoming Territory grants suffrage to women 1870 Utah Territory grants suffrage to women 1880 New York State grants school suffrage to women 1890 Wyoming joins the Union as the first state with voting rights for women. By 1900 women also have full suffrage in Utah, Colorado and Idaho. New Zealand is the first nation to give women suffrage 1902 Women of Australia are enfranchised. 1906 Women of Finland are enfranchised. 1912 Suffrage referendums are passed in Arizona, Kansas and Oregon 1913 territory of Alaska grants suffrage 1914 Montana and Nevada grant voting rights to women, 1915 Women of Denmark are enfranchised. 1917 Women win the right to vote in North Dakota, Ohio, Indiana, Rhode Island, Nebraska, Michigan, New York, and Arkansas 1918 Women of Austria, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Scotland, and Wales are enfranchised. 1919 Women of Azerbaijan Republic, Belgium, British East Africa, Holland, Iceland, Luxembourg, Rhodesia, and Sweden are enfranchised. Suffrage Amendment is passed by the US Senate on June 4th and the battle for ratification by at least 36 states begins. 1920 In February the LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS was formed by Carrie Chapman Catt at the close of the National American Women Suffrage Alliance last Convention. The League of Women Voters is to this day one of the country's preeminent nonpartisan voter education groups. -

(Microsoft Powerpoint

Milestones and Key Figures in Women’s History Life in Colonial America 1607-1789 Anne Hutchinson Challenged Puritan religious authorities in Massachusetts Bay Banned by Puritan authorities for: Challenging religious doctrine Challenging gender roles Challenging clerical authority Claiming to have had revelations from God Legal Status of Colonial Women Women usually lost control of their property when they married Married women had no separate legal identity apart from their husband Could NOT: Hold political office Serve as clergy Vote Serve as jurors Legal Status of Colonial Women Single women and widows did have the legal right to own property Women serving as indentured servants had to remain unmarried until the period of their indenture was over The Chesapeake Colonies Scarcity of women, especially in the 17 th century High mortality rate among men Led to a higher status for women in the Chesapeake colonies than those of the New England colonies The Early Republic 1789-1815 Abigail Adams An early proponent of women’s rights A famous letter to John demonstrates that some colonial women hoped to benefit from republican ideals of equality and individual rights “. And by the way in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Remember, men would be tyrants if they could.” --Abigail Adams The Cult of Domesticity / Republican Motherhood The term cult of domesticity refers to the idealization of women in their roles as wives and mothers The term republican mother suggested that women would be responsible for rearing their children to be virtuous citizens of the new American republic By emphasizing family and religious values, women could have a positive moral influence on the American political character The Cult of Domesticity / Republican Motherhood Middle-Class Americans viewed the home as a refuge from the world rather than a productive economic unit. -

Social Studies Summer Project

Person of Interest Project Assignment: The student will choose one person from the course, about whom we will learn, and research the person's life in detail. The student will record details and various pieces of informa<on about their chosen person in a format that is easily understood and will make an oral report. The student is responsible for finding credible informa<on from the internet, books, encyclopedias, etc. Objec<ve: The student's objec<ve is to learn proper research techniques, as well as grasping the importance of individuals throughout the course of U.S. History. People: Christopher Columbus Frederick Douglass John Paul Jones Pocahontas Meriwether Lewis Abigail Adams William Clark John Adams Stonewall Jackson Samuel Adams Susan B. Anthony Benjamin Franklin Elizabeth Cady Stanton King George III Jefferson Davis Patrick Henry Ulysses S. Grant Paul Revere Robert E. Lee Thomas Jefferson Abraham Lincoln the Marquis de LafayeXe John Quincy Adams Thomas Paine John C. Calhoun George Washington Henry Clay Eli Whitney Daniel Webster Alexander Hamilton Harriet Tubman James Madison Clara Barton James Monroe Mary Todd Lincoln Betsy Ross Harriet Beecher Stowe Andrew Jackson Nat Turner Thomas Hooker Charles de Montesquieu John Locke William Penn Instruc<ons: Find the following informa<on for your person of interest. AIer you have researched and found the necessary informa<on, create a poster/power point that includes all the informa<on you found, 3 pictures, and include an essay of at least 2 pages of how your person of interest impacted the United States and you must have all your informa<on and sources properly cited. -

Women's History Month

Women’s History Month Women’s History Month 2021: This year’s theme continues the centennial celebration of the ratification of Valiant Women of the Vote: the 19th Amendment on August 26, 1920, Refusing to be Silent giving women the right to vote. Last year’s original centennial celebration was put on hold because of Covid. The original Women’s History celebration began as the first week of March in 1982, and was eventually expanded in 1987 to be the entire month of March. Although women have made many gains in the last century and we look forward to spotlighting them here, we have to remember that ERA Amendment remains unratified. Mrs. Anderson’s Sociology Class Sandra Day O'Connor was born on March 16, 1930, in El Paso, Texas. O'Connor and her family grew up on a ranch in Sandra Day Arizona. She was very skilled at riding and worked on the farm. After graduating from Stanford University in 1950 with a bachelor's in economics, she attended law school and got her degree two years later. O'Connor struggled to find a job due to the lack of female O'Connor positions in the law industry, so she became a deputy county attorney. She continued to be a lawyer while traveling overseas and was given the opportunity to fill in a job by Governor Jack Williams. She won the election and reelection as a conservative republican. It didn't end there; O'connor took on an extreme challenge and ran for judge in the Maricopa County Supreme Court; fair enough, she won the race!.